Difference between revisions of "Monophysitism" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

Mongus' rival Talaia, meanwhile, had sent ambassadors to Pope Simplicius to notify him of his election. However, at the same time, the pope received a letter from the emperor in which Talaia was accused of perjury and bribery. The emperor insisted that under the circumstances, the pope should recognize Mongus. Simplicius thus hesitated to recognize Talaia, but he also protested against the elevation of Mongus to the patriarchate. Acacius, nevertheless, maintained his alliance with Mongus and sought to prevail upon the Eastern bishops to enter into [[communion]] with him. Acacius now broke off communication with Simplicius, and the pope later wrote and blamed Acacius severely for his lapse. Talaia himself came to Rome in 483, but Simplicius was already dead. Pope Felix III welcomed Talaia, repudiated the [[Henotikon]], and excommunicated Peter Mongus. | Mongus' rival Talaia, meanwhile, had sent ambassadors to Pope Simplicius to notify him of his election. However, at the same time, the pope received a letter from the emperor in which Talaia was accused of perjury and bribery. The emperor insisted that under the circumstances, the pope should recognize Mongus. Simplicius thus hesitated to recognize Talaia, but he also protested against the elevation of Mongus to the patriarchate. Acacius, nevertheless, maintained his alliance with Mongus and sought to prevail upon the Eastern bishops to enter into [[communion]] with him. Acacius now broke off communication with Simplicius, and the pope later wrote and blamed Acacius severely for his lapse. Talaia himself came to Rome in 483, but Simplicius was already dead. Pope Felix III welcomed Talaia, repudiated the [[Henotikon]], and excommunicated Peter Mongus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ----- | ||

| + | The first act of Pope Felix III was to repudiate the Henoticon, and address a letter of remonstrance to Acacius. When Acacius did not respond favorably Felix declared him deposed and excommunicited. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Felix excommunicated the Monophysite Bishop Peter the Fuller of Antioch who had been election against the pope's wishes. In 484, Felix also excommunicated Bishop [[Peter Mongus]] of Alexandria. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After Acacius' death in 489 an opportunity for ending the schism arose when he was succeeded by the orthodox Patriarch Euphemius. However, Pope [[Gelasius I]] insisted on the removal of his name of the much respected Acacius from the diptychs of Constantinope. Gelasius' book ''De duabus in Christo naturis'' ('On the dual nature of Christ') delineated the western view and set the papacy on a course of no compromise with Monophysitism. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (fill in data here) | ||

| + | In a letter to Emperor [[Anastasius I]] (491-518), Pope Symmachus defended the opponents of the ''[[Henotikon]]'', although without success. The Emperor was determined to put an end to the divisive debate over the question of Christ's natures. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Shortly after 506 the emperor wrote to Symmachus a letter full of invectives for daring to interfere both with imperial policy and the rights of the eastern patriarch, to whom he was superior in honor only. The pope replied with an equally firm answer, maintaining in the strongest terms the rights and Roman church as the representative of [[Saint Peter]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a letter of October, 8 512, addressed to the bishops of Illyria, the pope warned the clergy of that province not to hold communion with heretics, a direct assault on the principles of the [[Henotikon]]. | ||

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

Revision as of 12:15, 11 July 2008

| Part of the series on Eastern Christianity | |

| |

|

History | |

|

Traditions | |

|

Liturgy and Worship | |

|

Theology | |

Monophysitism (from the Greek monos meaning 'one, alone' and physis meaning 'nature') is the christological position that Christ has only one nature (divine), as opposed to the Chalcedonian position which holds that Christ has two natures, one divine and one human. The term also refers to the movement centered on this concept, which struggled against the Chalcedonian formula in the fifth through sixth centuries CE.

Monophysitism and its antithesis, Nestorianism, were both hotly disputed and divisive competing tenets in the maturing Christian traditions during the first half of the fifth century. Monophysitism grew to prominence in the Eastern Roman empire, particularly in Syria, the Levant, Egypt, and Anatolia, while the Western Roman empire remained for the most part under the religious influence of the papacy, which denounced the doctrine as heresy.

Two major doctrines are specifically associated with Monophysitism:

- Eutychianism, which held that the human and divine natures of Christ were fused into one new single (mono) nature.

- Apollinarianism, which held that, while Christ possessed a normal human body and emotions, the Divine Logos had basically taken the place of the nous, or mind.

The Eutychian form of Monophysitism emerged after the "diaphysite" doctrine of Nestorius, Archbishop of Constantinople, had been rejected at the First Council of Ephesus. Eutyches, also from Constantinople, emerged with a diametrally opposite view. Eutyches' was accused of heresy in 448, leading to his excommunication. In 449, at the controversial Second Council of Ephesus, Eutyches was reinstated and his chief opponents were deposed. However, Monophysitism and Eutyches were again rejected at the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

Monophysitism continued to have many adherents, however, and the controversy reemerged in a major way in late fifth century, in the form of the Acacian schism. In this drama, Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople and Emperor Zeno sought to reconcile the Monophysite and Chalcedonian Christians by means of the Henotikon, a document which essentially banned debate over the question of Christ's "natures." The schism lasted for several decades until the orthodox emperor Justin I reversed the policy of his predecessors and encouraged Patriarch John II of Constantinople to submit to the doctrine promulgated by Pope Hormisdas.

History

Background

The doctrine of Monophysitism can be seen as evolving in reaction to the "diaphysite" theory of Bishop Nestorius of Constantinople in the early fifth century. Nestorianism was an attempt to explain rationally the doctrine of the Incarnation, which held that God the Son had dwelt among men in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. Nestorius held that the human and divine essences of Christ were separate, so that the man Jesus and the divine Logos, were in effect two "persons," a similar sense of the Trinity being three "persons."[1] Consequently, Nestorians rejected such terminology as "God was crucified," because the humanity of Jesus Christ that suffered was distinct from his divinity. Likewise, Nestorius rejected the term Theotokos (God-bearer or Mother of God) as a title of the Virgin Mary, suggesting instead the title Christotokos (Mother of Christ), as more accurate.

Bishop Cyril of Alexandria led the theological criticism of Nestorius beginning 429. "I am amazed," he said, "that there are some who are entirely in doubt as to whether the holy Virgin should be called Theotokos or not." Pope Celestine I, who was suspicious of Nestorius for granting hospitality to certain certain Pelagian clerics whom the pope had condemned soon joined Cyril in condemning Nestorius. After considerable wrangling and intrigue the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus in 431 condemned Nestorianism as heresy. Nestorius himself was deposed as bishop of Constantinople and excommunicated.

Eutychianism

Cyril taught that in Christ, "There is only one physis, since it is the Incarnation, of God the Word." Only this sounds very much like Monophysitism, Cyril was apparently beyond reproach. Eutyches (c. 380—c. 456), a presbyter and archimandrite of a monastery of 300 monks near Constantinople, emerged after Cyril's death as Nestorianism's most vehement opponent. He held that Christ's divinity and humanity were perfectly united, and his vehement expression of this principle led to his being understood to insist that Christ had only one nature (essentially divine) rather than two.

Eutychianism became a major controversy among the eastern church and Pope Leo I, from Rome, wrote that Eutyches teaching was indeed an error, although he admitted that it seemed to be more from a lack of skill on the matters than from malice. Nevertheless, Eutyches found himself denounced as a heretic in November 447, during a local synod in Constantinople. Archbishop Flavian of Constantinople did not wish the council to consider the matter due to the great prestige that Eutyches enjoyed, but he finally relented, and Eutyches was condemned as a heretic by the synod. However, the emperor Theodosius II and the Patriarch Dioscorus of Alexandria did not accept this decision. Dioscorus held his own synod at Alexandria reinstating Eutyches, and the emperor called a council to be held in Ephesus in 449, inviting Pope Leo I, who agreed to be represented by four legates.

The Second Council of Ephesus convened on August 8, 449, with some 130 bishops in attendance. Dioscorus of Alexandria presided by command of the emperor, who denied a vote to any bishop who had voted in Eutyches' deposition two years earlier. As a result, there was a near-unanimous support for Eutyches—the pope's representatives being among the few who insisted on Eutyches' being in error. Moreover, the council went so far as to condemn and expel Archbishop Flavian of Constantinople, who soon died.

The decisions of this council threatened schism between the East and the West, and soon became known in the west as the "Robber Synod."

Chalcedon

The situation continued to deteriorate until the ascension of Emperor Marcian to the imperial throne, brought about a reversal of policy in the East. The Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon was now convened in 451, under terms less favorable to the Monophysites. It promulgated the doctrine which ultimately—though not without serious challenges—stood as the settled christological formula for most of Christendom. Eutychianism was once again rejected, and the formula of "two natures without confusion, change, division, or separation" was adopted.

- "We confess that one and the same Christ, Lord, and only-begotten Son, is to be acknowledged in two natures without confusion, change, division, or separation. The distinction between natures was never abolished by their union, but rather the character proper to each of the two natures was preserved as they came together in one person and one hypostasis."

Although this settled matters between Constantinople and Rome on the christological issue, a new controversy arose as a result of Chalcedon's canon number 28, granting Constantinople, as "New Rome" equal ecclesiastical privileges with "old" Rome. This, of course, was unacceptable to the pope, who accepted the council's theological points, but not its findings on church disciple.

Pope Simplicius role

Monophysitism continued to be a major movement in many eastern provinces, with popular sentiment on both sides of the issue sometimes breaking out into violence over the nomination of various bishops in cities often divided by Monophysite and Chalcedonian factions. In 474, Emperor Leo II sought Pope Simplicius' confirmation of Constantinople's status as "New Rome" and its rights to nominate bishops of certain cities previously under the pope's jurisdiction. Simplicius rejected the emperor's request.

In 476, after Leo II's death, Flavius Basiliscus drove the new emperor, Zeno, into exile and seized the Byzantine throne. Basiliscus looked to the Monophysites for support, and he allowed the deposed Monophysite patriarchs Timotheus Ailurus of Alexandria and Peter Fullo of Antioch to return to their sees. At the same time Basiliscus issued a religious edict which commanded that only the first three ecumenical councils were to be accepted, rejecting the Council of Chalcedon. All eastern bishops were commanded to sign the edict. The patriarch of Constantinople, Acacius, wavered; but a popular outcry led by rigidly orthodox monks moved the him to resist the emperor and to reject his overtures to the Monophysites.

When the former emperor, Zeno, regained power from Basiliscus in 477, he sent the pope an orthodox confession of faith, whereupon Simplicius congratulated him on his restoration to power. Zeno promptly voided the edicts of Basiliscus, banished Peter Fullo from Antioch, and reinstated Timotheus Salophakiolus at Alexandria. At the same time, he also allowed the Monophysite Patriarch Timotheus Ailurus to retain his office in the same city, reportedly on account of the latter's great age, although no doubt also because of the strength of the Monophysite adherents there. In any case, Ailurus soon died. The Monophysites of Alexandria now put forward Peter Mongus, the former archdeacon of Ailurus, as his successor. Urged by the pope and the orthodox parties of the east, Zeno commanded that Peter Mongus be banished. Peter, however, was able to remain in Alexandria, and fear of the Monophysites prevented the use of force.

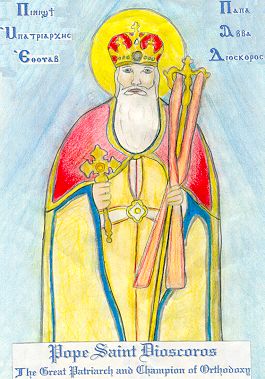

Meanwhile the orthodox Patriarch Timotheus Salophakiolus, apparently seeking conciliation, risked the ire of the anti-Monophysites by placing of the name of the respected deceased Monophysite patriarch Dioscurus I on the diptychs, the list of honored leaders to be read at the church services. Simplicius wrote to Acacius of Constantinople on March 13, 478 urging that Salophakiolus should be commanded to reverse himself on this matter. Salophakiolus sent legates and letters to Rome to assure the pope that Dioscorus' name would be removed from the lists.

Patriarch Acacius continued his campaign against the Monophysistes, and at his request Pope Simplicius condemned by name the previously named "heretics" Mongus and Fullo, as well as several others. The pope also named Acacius as his representative in the matter. When the Monophysites at Antioch raised a revolt in 497 against anti-Monophysite Patriarch Stephen II and killed him, Acacius himself chose and consecrated Stephen's successors. Simplicius demanded that the emperor punish the murderers of the patriarch, but—ever vigilant to defend Rome's prerogatives—strongly reproved Acacius for allegedly exceeding his competence in performing the consecration of Stephen III. Relations between the patriarchs of the two great cities now soured considerably.

The Acacian schism

After the death of Salophakiolus, the Monophysites of Alexandria again elected Peter Mongus patriarch, while the orthodox chose Johannes Talaia. Despite Acacius' earlier opinion that Mongus was a heretic, both Acacius and the emperor were opposed to Talaia and sided with Mongus, perhaps on the grounds that his moral reputation was superior. When Mongus came to Constantinople to advance his cause, Acacius and he agreed upon a formula of union between the Catholics and the Monophysites—the Henotikon—that was approved by the Emperor Zeno in 482. This document essentially banned further debate on the subject of Christ's nature(s).

Mongus' rival Talaia, meanwhile, had sent ambassadors to Pope Simplicius to notify him of his election. However, at the same time, the pope received a letter from the emperor in which Talaia was accused of perjury and bribery. The emperor insisted that under the circumstances, the pope should recognize Mongus. Simplicius thus hesitated to recognize Talaia, but he also protested against the elevation of Mongus to the patriarchate. Acacius, nevertheless, maintained his alliance with Mongus and sought to prevail upon the Eastern bishops to enter into communion with him. Acacius now broke off communication with Simplicius, and the pope later wrote and blamed Acacius severely for his lapse. Talaia himself came to Rome in 483, but Simplicius was already dead. Pope Felix III welcomed Talaia, repudiated the Henotikon, and excommunicated Peter Mongus.

The first act of Pope Felix III was to repudiate the Henoticon, and address a letter of remonstrance to Acacius. When Acacius did not respond favorably Felix declared him deposed and excommunicited.

Felix excommunicated the Monophysite Bishop Peter the Fuller of Antioch who had been election against the pope's wishes. In 484, Felix also excommunicated Bishop Peter Mongus of Alexandria.

After Acacius' death in 489 an opportunity for ending the schism arose when he was succeeded by the orthodox Patriarch Euphemius. However, Pope Gelasius I insisted on the removal of his name of the much respected Acacius from the diptychs of Constantinope. Gelasius' book De duabus in Christo naturis ('On the dual nature of Christ') delineated the western view and set the papacy on a course of no compromise with Monophysitism.

(fill in data here) In a letter to Emperor Anastasius I (491-518), Pope Symmachus defended the opponents of the Henotikon, although without success. The Emperor was determined to put an end to the divisive debate over the question of Christ's natures.

Shortly after 506 the emperor wrote to Symmachus a letter full of invectives for daring to interfere both with imperial policy and the rights of the eastern patriarch, to whom he was superior in honor only. The pope replied with an equally firm answer, maintaining in the strongest terms the rights and Roman church as the representative of Saint Peter.

In a letter of October, 8 512, addressed to the bishops of Illyria, the pope warned the clergy of that province not to hold communion with heretics, a direct assault on the principles of the Henotikon.

Legacy

Monophysitism is also rejected by the Oriental Orthodox Churches, but was widely accepted in Syria, the Levant, and Egypt leading to many tensions in the early days of the Byzantine Empire.

Later, Monothelitism was developed as an attempt to bridge the gap between the Monophysite and the Chalcedonian position, but it too was rejected by the members of the Chalcedonian synod, despite at times having the support of the Byzantine emperors and one of the Popes of Rome, Honorius I. Some are of the opinion that Monothelitism was at one time held by the Maronites, but the Maronite community, for the most part, dispute this, stating that they have never been out of communion with the Catholic Church.

Miaphysitism, the christology of the Oriental Orthodox churches, is sometimes considered a variant of Monophysitism, but these churches view their theology as distinct from Monophysitism and anathematize Eutyches.

See also

- Diophysitism

- Acephali

- Henotikon

- the Three-Chapter Controversy

- Christ the Logos

- West Syrian Rite

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agreed Statements between representative of the Oriental and Eastern Orthodox Churches

- Joint Declaration by the Oriental and the Catholic Church

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ The Greek word hypostasis, translated into Latin as "persona" does not carry quite the same sense of distinction as the Latin, a factor that has contributed to the many theological misunderstandings between eastern and western Christianity, both during this and other theological controversies.