Difference between revisions of "Money supply" - New World Encyclopedia

m ({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Economics]] | [[Category:Economics]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}} |

| − | {{ | + | {{Public finance}} |

| + | '''Money supply''', "monetary aggregates" or "money stock" is a [[macroeconomics|macroeconomic]] concept defining the quantity of [[money]] available within a nation’s economy which can be used to purchase [[consumer good|goods]], services, or financial [[securities]]. A nation’s money supply is comprised of all [[currency]] including bills, [[coin]]s, and deposits issued by the nation’s [[central bank]]. Reserves mark the sum of all bank vault values and all reserve deposits held by the central bank. Combined, a nation’s currency and the level of bank reserves comprise the total money supply, or monetary base. Total money supplies are generally measured by the sum of currency in circulation, checking deposits, and saving deposits. The [[United States|U.S.]] [[Federal Reserve]] uses three definitions of money to measure its money supply; M1 which measures money in exchange, M2 which measures money in storage, and M3 which measures objects that can act as money substitutes. Generally, central banks regulate the money supply through the operation of various [[monetary policy|monetary policies]], in efforts to stabilize their economy. While it is agreed that the money supply of a country is a significant factor, understanding how to best regulate it in order to promote a healthy economy is less clear. As humankind develops greater maturity, learning to live harmoniously for the sake of others, our understanding of how to regulate the money supply will also develop and be able to be implemented successfully, supporting the maintenance of a peaceful world of harmony and co-prosperity. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==Monetary Aggregates== | ||

| + | Different measures of a nation's money supply reflect various degrees of asset [[liquidity]], which marks the ease at which a monetary asset can be turned into cash. Liquid assets include [[coin]]s, paper [[currency]], checkable-type deposits, and traveler’s checks. Less liquid assets include money market deposits and saving account deposits. Measure MI, the most narrow of measures, includes only the most liquid forms of monetary assets&dmash;all currency and bank deposits held by a nation’s public. M2, a slightly broader measure includes all values incorporated under MI, in addition to assets held in savings accounts, certain time deposits and mutual fund balances. | ||

| − | + | ===The United States=== | |

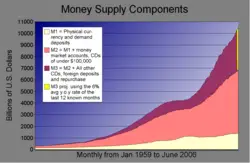

| − | + | [[Image:Money-supply.png|thumb|right|250 px|U.S. Money Supply from 1959-2006]] | |

| − | == | + | Under the U.S. [[Federal Reserve]], the most common measures of money supply are termed M0, M1, M2, and M3. The Federal Reserve defines such measures as follows: |

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Image:Money-supply.png|thumb|right|U.S. Money Supply from 1959-2006]] | ||

* '''M0''': The total of all physical [[currency]], plus accounts at the central bank which can be exchanged for physical currency. | * '''M0''': The total of all physical [[currency]], plus accounts at the central bank which can be exchanged for physical currency. | ||

| − | * '''M1''': M0 | + | * '''M1''': Measure '''M0''' plus the amount in demand accounts, including "checking" or "current" accounts. |

| − | * '''M2''': M1 | + | * '''M2''': Measure '''M1''' plus most savings accounts, money market accounts, and certificate of deposit (CD) accounts of under $100,000. |

| − | * '''M3''': | + | * '''M3''': Measure '''M2''' plus all other CDs, deposits of eurodollars and repurchase agreements. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | ===The United Kingdom=== |

| + | Within the [[United Kingdom]], there are just two official money supply measures. M0, which is referred to as the "wide monetary base" or "narrow money," and M4, which is referred to as "broad money" or simply "the money supply." These measures are defined as such: | ||

| + | * '''M0''': All cash outside the Bank of England plus private banks' operational deposits with the Bank of England. | ||

| + | * '''M4''': All cash outside banking institutes, either in circulation with the public and non-bank firms, plus private-sector retail bank and building society deposits plus private-sector wholesale bank and building society deposits and certificates of deposits. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Determination== |

| + | A nation’s money supply is determined by the [[monetary policy]] actions of its [[central bank]]. [[Commercial bank]]s, as required by the central bank, must keep a fraction of all accepted deposits on reserve either in bank vaults or in central bank deposits. Accordingly, a nation’s central bank can maintain control of such reserves by lending to commercial banks and altering the [[rate of interest]] to be charged on such loans. These actions are known as [[open market operations]] and allow central banks to achieve a desired level of reserves. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In determining a nation’s money supply, its central bank first sets the supply of the monetary base and upholds certain restrictions on the value of assets and liabilities held by smaller commercial banks. Though the consumer demand for liquidity is dictated by the public, small commercial banks are required to meet consumer demand and do so by identifying certain conditions including a set interest rate which apply to the loaning of bank liabilities. Commercial bank behavior, ultimately regulated by the nation’s central banking institution, and conjunction with consumer demand define the total stock of money, bank credit, and rates of interest which shape national economic conditions. | ||

| − | + | The value of the money supply is determined by the money multiplier and the monetary base. The monetary base consists of the total quantity of government-produced money and includes all [[currency]] held by the public and reserves held by commercial banks. The central bank retains tight control over its nation’s money supply through the use of open market operations, the discount rate, and reserve requirements. | |

| − | == | + | ===Money Multiplier=== |

| + | The money multiplier is jointly determined by the economic behavior of consumers, [[commercial bank]]s, and the [[central bank]]. Factors which limit the money multiplier include consumer expectations and their decisions to hold money, and the liquidity preferences of commercial banks to hold excess reserves. In short, the money multiplier must account for various levels of consumer demand, private bank demands, and any resulting [[market]] conditions. | ||

| − | + | The value of the money multiplier is directly related to consumer behavior in that an increase in the demand for money will subsequently decrease the size of the money multiplier. An increase in the demand for excess reserves by private banks will also diminish the money multiplier, decreasing with it the value of the money supply, the amount of bank loans, and deposits. Changes in the money multiplier represent short-run fluctuations and often denote temporary changes to the total money supply. | |

| − | == | + | ===Monetary Base=== |

| − | + | A nation’s monetary base constitutes its total money supply. It defines the volume of money within the economy and is comprised of [[currency]], banknotes, [[coin]]s, and commercial bank reserves held by the central bank. A narrow definition of the money supply, the monetary base consists of only the most liquid forms of [[money]] and can be controlled by a nation’s [[central bank]] through its use of monetary policy in particular the employment of [[open market operation]]s. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Central Bank Policies== |

| − | + | A nation’s money supply is closely tied to all levels of its economic activity. Short-run changes in a nation’s money supply may prove to have immediate economic effects on employment levels, output levels, and real income levels, while the long-run behavior of a nation’s money supply often determines levels of price [[inflation]]. Increases in a nation’s money supply have been shown to increase levels of aggregate [[demand]], raising with it spending levels, production, the demand for [[labor]] and for [[capital]] goods. A decrease in a nation’s money supply has been shown to reverse such effects—consumer demand falls, spending levels tighten and the level of economic activity declines. A nation’s central bank can alter is total money supply by employing open market operations, changes in the discount rate, or alterations to reserve requirements. | |

| − | === | + | ===Open Market Operations=== |

| − | + | Open market operations, the most dominant instrument of monetary policy, is the behavior of a nation’s [[central bank]] to trade or purchase government securities for cash in attempts to expand or contract the total money supply. While purchases of government securities prove to expand the total monetary base, the selling of government securities will ultimately contract a nation’s monetary base. | |

| − | + | ===Reserve Requirements=== | |

| + | Under fractional reserve banking, a nation’s [[central bank]] is responsible for holding a certain fraction of all deposits as cash or on account with the central bank. Central banks may alter the total money supply by changing the required percentage of total deposits to be held by [[commercial bank]]s. An increase in reserve requirements would decrease the monetary base; a decrease in the requirements would increase the monetary base. | ||

| − | + | ===Discount Rate=== | |

| − | + | A nation’s [[central bank]] is also responsible for supplying [[commercial bank]]s with enough currency to meet consumer [[demand]]. By controlling the national [[interest rate]], a central bank can adequately meet and further dictate the consumer demand for money. A decrease in the interest rate will spark an increase in the consumer demand for money; an increase in the rate of interest will lessen its demand. Changes in the interest rate also play a role in the setting of [[price]] levels. Any increase in the demand for money will increase spending levels and cause prices to rise. A decrease in the demand for money will slow spending levels and produce a subsequent decrease in price levels. If consumers expect price levels to fall, the demand for money will increase. If consumers expect price levels to increase, the demand for money will decline. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Monetary Objectives== | |

| − | + | Though a nation’s money supply delineates the total amount of [[money]] within a national economy, nations also employ various methods or principles to measure their total money stock. Similarly, a nation’s [[central bank]]ing institution retains various monetary objectives to ensure national economic stability. Some objectives belonging to the [[Money supply#The Federal Reserve|Federal Reserve]], the [[Money supply#The Bank of England|Bank of England]] and the [[Money supply#The European Central Bank|European Central Bank]] are listed below. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===The Federal Reserve=== |

| − | + | The U.S. [[Federal Reserve]] is responsible for monitoring the money supply of the [[United States]]. When aiming to expand the U.S. money supply by means of expansive [[monetary policy]], the Federal Reserve adds more reserves to the banking system in order to allow private banks more liquidity and ensure their ability to issue loans. The Federal Reserve aims to foster economic growth within the United States by maintaining stability within the national money supply and regulating the actions of private banking institutions throughout the U.S. | |

| − | + | ===The Bank of England=== | |

| + | The [[Bank of England]] is the [[central bank]]ing institution of the [[United Kingdom]], retaining control over its money supply and the determination of its [[interest]] rate. The Bank of England is responsible for controlling the U.K.’s [[foreign exchange]] rates and [[gold reserve]]s and aims toward ensuring monetary and financial stability. The interest rate set by the Bank of England is set through financial market operations and dictates the rate at which the Bank of England lends credit to various financial institutions. The Bank retains a [[monopoly]] on the issuance of banknotes within the United Kingdom and, under the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee, aims to set a general interest rate that meets an overall economic inflation target. | ||

| − | + | ===The European Central Bank=== | |

| + | The [[European Central Bank]] (ECB), is responsible for controlling the money supply and setting the rate of [[interest]], or the discount rate, for the countries that comprise the [[European Union]]. The main objective of the ECB is to ensure price stability and to limit inflationary pressures that constrain consumer purchasing power throughout the EU. In order to maintain economic health, contemporary ECB policies have targeted annual [[inflation]] rates that ensure less than two percent increases in consumer price levels. By retaining tight control of the money supply to limit inflation levels, and by further monitoring present and past [[price]] trends, the ECB aims to adequately assess the risks to price stability and attempt to assuage them. | ||

| − | + | ==Policy Criticism== | |

| + | [[Image:Us proportionate m3.svg|thumb|left|250 px|U.S. M3 money supply as a proportion of gross domestic product.]] One of the principal jobs of [[central bank]]s, such as the U.S. [[Federal Reserve]], the [[Bank of England]] and the [[European Central Bank]], is to keep money supply growth in line with real [[Gross Domestic Product]] (GDP) growth. Central banks do this primarily by targeting some inter-bank interest rate. In the United States, this is the federal funds rate obtained through the use of [[open market operation]]s. | ||

| − | + | A very common criticism of this target policy is that "real GDP growth" is, in fact, meaningless and since GDP can grow for many reasons including man-made disasters and crises, is not correlated with any known means of measurement well-being. The policy use of GDP figures is considered to be an abuse, and a common solution proposed by such critics is that a nation’s money supply should be kept in line with a more ecological, social and human mean of well-being. In theory, money supply would expand when well-being is improving and contract when well-being is decreasing. Proponents believe this policy to give all parties in the economy a direct interest in improving well-being. | |

| − | + | This argument must be balanced against the standard view among economists: that the control of [[inflation]] is the main job of a central bank, and that any introduction of non-financial means of measuring well-being has an inevitable "domino effect" of increasing [[government]] spending and diluting [[capital]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Currency]] integration is thought by some economists, including [[Nobel Prize]] winner [[Robert Mundell]], to alleviate this problem by ensuring that currencies become less competitive in the commodity [[market]]s, and that a wider [[politics|political]] base be employed in the setting of currency and [[inflation]] and well-being policy. This thinking is in part the basis of the [[Euro]] currency integration within the [[European Union]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Some economists argue for the money supply to remain constant at all times. With growth in production, this would result in falling prices. A constant money supply would keep nominal incomes constant over time; however falling prices lead to an increase in real incomes. Due to such conflict, policy regarding a nation’s money supply remains one of the most controversial aspects of [[economics]] itself. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ==References== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *Federal Reserve Bank of New York. [http://www.ny.frb.org/aboutthefed/fedpoint/fed49.html ''The Money Supply'']. Retrieved July 20, 2007. | ||

| + | *Hussman, John P. ''Breaking Monetary Policy into Pieces''. Hussman Funds Weekly Market Comment. [http://www.hussmanfunds.com/wmc/wmc040524.htm Hussman Funds] Retrieved July 20, 2007. | ||

| + | *Ingham, Geoffrey. ''The Nature of Money''. Polity Press, 2004. ISBN 074560997X | ||

| + | *Mzumara, Macleans. ''The Theory of Money and Banking in Modern Times''. Tate Publishing & Enterprises, 2006. ISBN 1933290021 | ||

| + | *Schwartz, Anna J. ''Money in Historical Perspective''. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press, 1989. ISBN 0226742288 | ||

| + | *Schwartz, Anna J. [http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/MoneySupply.html ''Money Supply'']. The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Retrieved July 20, 2007. | ||

| + | ==External Links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 9, 2022. | ||

| + | *[http://www.frbsf.org/education/activities/drecon/2001/0111.html Do All Banks Hold Reserves, and, if so, Where Do They Hold Them? (11/2001)] | ||

| + | *[http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/current/h6.htm Money Stock Measures (H.6)] | ||

| + | *[http://www.bullandbearwise.com/MoneySupplyChart.asp Trailing Five-Year U.S. Money Supply Chart] | ||

| + | *[http://www.bullandbearwise.com/MoneySupplyChgChart.asp Trailing Five-Year U.S. Money Supply Rate of Change Chart] | ||

| + | *[http://www.frbsf.org/education/activities/drecon/2001/0108.html What Effect Does a Change in the Reserve Requirement Have on the Money Supply? (08/2001)] | ||

{{credit1|Money_supply|87810786|}} | {{credit1|Money_supply|87810786|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:56, 9 November 2022

| Public finance |

|

| This article is part of the series: Finance and Taxation |

| Taxation |

|---|

| Ad valorem tax · Consumption tax Corporate tax · Excise Gift tax · Income tax Inheritance tax · Land value tax Luxury tax · Poll tax Property tax · Sales tax Tariff · Value added tax |

| Tax incidence |

| Flat tax · Progressive tax Regressive tax · Tax haven Tax rate |

| Economic policy |

| Monetary policy Central bank · Money supply |

| Fiscal policy Spending · Deficit · Debt |

| Trade policy Tariff · Trade agreement |

| Finance |

| Financial market Financial market participants Corporate · Personal Public · Banking · Regulation |

Money supply, "monetary aggregates" or "money stock" is a macroeconomic concept defining the quantity of money available within a nation’s economy which can be used to purchase goods, services, or financial securities. A nation’s money supply is comprised of all currency including bills, coins, and deposits issued by the nation’s central bank. Reserves mark the sum of all bank vault values and all reserve deposits held by the central bank. Combined, a nation’s currency and the level of bank reserves comprise the total money supply, or monetary base. Total money supplies are generally measured by the sum of currency in circulation, checking deposits, and saving deposits. The U.S. Federal Reserve uses three definitions of money to measure its money supply; M1 which measures money in exchange, M2 which measures money in storage, and M3 which measures objects that can act as money substitutes. Generally, central banks regulate the money supply through the operation of various monetary policies, in efforts to stabilize their economy. While it is agreed that the money supply of a country is a significant factor, understanding how to best regulate it in order to promote a healthy economy is less clear. As humankind develops greater maturity, learning to live harmoniously for the sake of others, our understanding of how to regulate the money supply will also develop and be able to be implemented successfully, supporting the maintenance of a peaceful world of harmony and co-prosperity.

Monetary Aggregates

Different measures of a nation's money supply reflect various degrees of asset liquidity, which marks the ease at which a monetary asset can be turned into cash. Liquid assets include coins, paper currency, checkable-type deposits, and traveler’s checks. Less liquid assets include money market deposits and saving account deposits. Measure MI, the most narrow of measures, includes only the most liquid forms of monetary assets&dmash;all currency and bank deposits held by a nation’s public. M2, a slightly broader measure includes all values incorporated under MI, in addition to assets held in savings accounts, certain time deposits and mutual fund balances.

The United States

Under the U.S. Federal Reserve, the most common measures of money supply are termed M0, M1, M2, and M3. The Federal Reserve defines such measures as follows:

- M0: The total of all physical currency, plus accounts at the central bank which can be exchanged for physical currency.

- M1: Measure M0 plus the amount in demand accounts, including "checking" or "current" accounts.

- M2: Measure M1 plus most savings accounts, money market accounts, and certificate of deposit (CD) accounts of under $100,000.

- M3: Measure M2 plus all other CDs, deposits of eurodollars and repurchase agreements.

The United Kingdom

Within the United Kingdom, there are just two official money supply measures. M0, which is referred to as the "wide monetary base" or "narrow money," and M4, which is referred to as "broad money" or simply "the money supply." These measures are defined as such:

- M0: All cash outside the Bank of England plus private banks' operational deposits with the Bank of England.

- M4: All cash outside banking institutes, either in circulation with the public and non-bank firms, plus private-sector retail bank and building society deposits plus private-sector wholesale bank and building society deposits and certificates of deposits.

Determination

A nation’s money supply is determined by the monetary policy actions of its central bank. Commercial banks, as required by the central bank, must keep a fraction of all accepted deposits on reserve either in bank vaults or in central bank deposits. Accordingly, a nation’s central bank can maintain control of such reserves by lending to commercial banks and altering the rate of interest to be charged on such loans. These actions are known as open market operations and allow central banks to achieve a desired level of reserves.

In determining a nation’s money supply, its central bank first sets the supply of the monetary base and upholds certain restrictions on the value of assets and liabilities held by smaller commercial banks. Though the consumer demand for liquidity is dictated by the public, small commercial banks are required to meet consumer demand and do so by identifying certain conditions including a set interest rate which apply to the loaning of bank liabilities. Commercial bank behavior, ultimately regulated by the nation’s central banking institution, and conjunction with consumer demand define the total stock of money, bank credit, and rates of interest which shape national economic conditions.

The value of the money supply is determined by the money multiplier and the monetary base. The monetary base consists of the total quantity of government-produced money and includes all currency held by the public and reserves held by commercial banks. The central bank retains tight control over its nation’s money supply through the use of open market operations, the discount rate, and reserve requirements.

Money Multiplier

The money multiplier is jointly determined by the economic behavior of consumers, commercial banks, and the central bank. Factors which limit the money multiplier include consumer expectations and their decisions to hold money, and the liquidity preferences of commercial banks to hold excess reserves. In short, the money multiplier must account for various levels of consumer demand, private bank demands, and any resulting market conditions.

The value of the money multiplier is directly related to consumer behavior in that an increase in the demand for money will subsequently decrease the size of the money multiplier. An increase in the demand for excess reserves by private banks will also diminish the money multiplier, decreasing with it the value of the money supply, the amount of bank loans, and deposits. Changes in the money multiplier represent short-run fluctuations and often denote temporary changes to the total money supply.

Monetary Base

A nation’s monetary base constitutes its total money supply. It defines the volume of money within the economy and is comprised of currency, banknotes, coins, and commercial bank reserves held by the central bank. A narrow definition of the money supply, the monetary base consists of only the most liquid forms of money and can be controlled by a nation’s central bank through its use of monetary policy in particular the employment of open market operations.

Central Bank Policies

A nation’s money supply is closely tied to all levels of its economic activity. Short-run changes in a nation’s money supply may prove to have immediate economic effects on employment levels, output levels, and real income levels, while the long-run behavior of a nation’s money supply often determines levels of price inflation. Increases in a nation’s money supply have been shown to increase levels of aggregate demand, raising with it spending levels, production, the demand for labor and for capital goods. A decrease in a nation’s money supply has been shown to reverse such effects—consumer demand falls, spending levels tighten and the level of economic activity declines. A nation’s central bank can alter is total money supply by employing open market operations, changes in the discount rate, or alterations to reserve requirements.

Open Market Operations

Open market operations, the most dominant instrument of monetary policy, is the behavior of a nation’s central bank to trade or purchase government securities for cash in attempts to expand or contract the total money supply. While purchases of government securities prove to expand the total monetary base, the selling of government securities will ultimately contract a nation’s monetary base.

Reserve Requirements

Under fractional reserve banking, a nation’s central bank is responsible for holding a certain fraction of all deposits as cash or on account with the central bank. Central banks may alter the total money supply by changing the required percentage of total deposits to be held by commercial banks. An increase in reserve requirements would decrease the monetary base; a decrease in the requirements would increase the monetary base.

Discount Rate

A nation’s central bank is also responsible for supplying commercial banks with enough currency to meet consumer demand. By controlling the national interest rate, a central bank can adequately meet and further dictate the consumer demand for money. A decrease in the interest rate will spark an increase in the consumer demand for money; an increase in the rate of interest will lessen its demand. Changes in the interest rate also play a role in the setting of price levels. Any increase in the demand for money will increase spending levels and cause prices to rise. A decrease in the demand for money will slow spending levels and produce a subsequent decrease in price levels. If consumers expect price levels to fall, the demand for money will increase. If consumers expect price levels to increase, the demand for money will decline.

Monetary Objectives

Though a nation’s money supply delineates the total amount of money within a national economy, nations also employ various methods or principles to measure their total money stock. Similarly, a nation’s central banking institution retains various monetary objectives to ensure national economic stability. Some objectives belonging to the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank are listed below.

The Federal Reserve

The U.S. Federal Reserve is responsible for monitoring the money supply of the United States. When aiming to expand the U.S. money supply by means of expansive monetary policy, the Federal Reserve adds more reserves to the banking system in order to allow private banks more liquidity and ensure their ability to issue loans. The Federal Reserve aims to foster economic growth within the United States by maintaining stability within the national money supply and regulating the actions of private banking institutions throughout the U.S.

The Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central banking institution of the United Kingdom, retaining control over its money supply and the determination of its interest rate. The Bank of England is responsible for controlling the U.K.’s foreign exchange rates and gold reserves and aims toward ensuring monetary and financial stability. The interest rate set by the Bank of England is set through financial market operations and dictates the rate at which the Bank of England lends credit to various financial institutions. The Bank retains a monopoly on the issuance of banknotes within the United Kingdom and, under the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee, aims to set a general interest rate that meets an overall economic inflation target.

The European Central Bank

The European Central Bank (ECB), is responsible for controlling the money supply and setting the rate of interest, or the discount rate, for the countries that comprise the European Union. The main objective of the ECB is to ensure price stability and to limit inflationary pressures that constrain consumer purchasing power throughout the EU. In order to maintain economic health, contemporary ECB policies have targeted annual inflation rates that ensure less than two percent increases in consumer price levels. By retaining tight control of the money supply to limit inflation levels, and by further monitoring present and past price trends, the ECB aims to adequately assess the risks to price stability and attempt to assuage them.

Policy Criticism

One of the principal jobs of central banks, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, is to keep money supply growth in line with real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth. Central banks do this primarily by targeting some inter-bank interest rate. In the United States, this is the federal funds rate obtained through the use of open market operations.

A very common criticism of this target policy is that "real GDP growth" is, in fact, meaningless and since GDP can grow for many reasons including man-made disasters and crises, is not correlated with any known means of measurement well-being. The policy use of GDP figures is considered to be an abuse, and a common solution proposed by such critics is that a nation’s money supply should be kept in line with a more ecological, social and human mean of well-being. In theory, money supply would expand when well-being is improving and contract when well-being is decreasing. Proponents believe this policy to give all parties in the economy a direct interest in improving well-being.

This argument must be balanced against the standard view among economists: that the control of inflation is the main job of a central bank, and that any introduction of non-financial means of measuring well-being has an inevitable "domino effect" of increasing government spending and diluting capital.

Currency integration is thought by some economists, including Nobel Prize winner Robert Mundell, to alleviate this problem by ensuring that currencies become less competitive in the commodity markets, and that a wider political base be employed in the setting of currency and inflation and well-being policy. This thinking is in part the basis of the Euro currency integration within the European Union.

Some economists argue for the money supply to remain constant at all times. With growth in production, this would result in falling prices. A constant money supply would keep nominal incomes constant over time; however falling prices lead to an increase in real incomes. Due to such conflict, policy regarding a nation’s money supply remains one of the most controversial aspects of economics itself.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The Money Supply. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- Hussman, John P. Breaking Monetary Policy into Pieces. Hussman Funds Weekly Market Comment. Hussman Funds Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- Ingham, Geoffrey. The Nature of Money. Polity Press, 2004. ISBN 074560997X

- Mzumara, Macleans. The Theory of Money and Banking in Modern Times. Tate Publishing & Enterprises, 2006. ISBN 1933290021

- Schwartz, Anna J. Money in Historical Perspective. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press, 1989. ISBN 0226742288

- Schwartz, Anna J. Money Supply. The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

External Links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Do All Banks Hold Reserves, and, if so, Where Do They Hold Them? (11/2001)

- Money Stock Measures (H.6)

- Trailing Five-Year U.S. Money Supply Chart

- Trailing Five-Year U.S. Money Supply Rate of Change Chart

- What Effect Does a Change in the Reserve Requirement Have on the Money Supply? (08/2001)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.