Lughnasadh

| Lughnasadh | |

|---|---|

| Also called | Lúnasa (Modern Irish) Lùnastal (Scottish Gaelic) Luanistyn (Manx Gaelic) |

| Observed by | Historically: Gaels Today: Irish people, Scottish people, Manx people, Celtic neopagans |

| Type | Cultural, Pagan (Celtic polytheism, Celtic Neopaganism) |

| Significance | Beginning of the harvest season |

| Date | Sunset on 31 July – Sunset on 1 August (Northern Hemisphere) |

| Celebrations | Offering of First Fruits, feasting, handfasting, fairs, athletic contests |

| Related to | Calan Awst, Lammas |

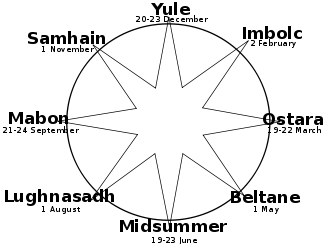

Lughnasadh or Lughnasa (pronounced LOO-nə-sə; Irish: Lúnasa; Scottish Gaelic: Lùnastal; Template:Lang-gv) is a Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season that was historically observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Originally it was held on 31 July – 1 August, or approximately halfway between the summer solstice and autumn equinox. However, over time the celebrations shifted to the Sundays nearest this date. Lughnasadh is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals; along with Samhain, Imbolc, and Beltane. It corresponds to other European harvest festivals, such as the Welsh Calan Awst and the English Lammas.

Lughnasadh is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature and is believed to have pagan origins. The festival itself is named after the god Lugh. It involved great gatherings that included religious ceremonies, ritual athletic contests (most notably the Tailteann Games), feasting, matchmaking and trading. There were also visits to holy wells. According to folklorist Máire MacNeill, evidence shows that the religious rites included an offering of the first of the corn, a feast of the new food and of bilberries, the sacrifice of a bull and a ritual dance-play. Much of this would have taken place on top of hills and mountains.

Lughnasadh customs persisted widely until the twentieth century, with the event being variously named 'Garland Sunday', 'Bilberry Sunday', 'Mountain Sunday', and 'Crom Dubh Sunday'. The custom of climbing hills and mountains at Lughnasadh has survived in some areas, although it has been re-cast as a Christian pilgrimage. The best known is the 'Reek Sunday' pilgrimage to the top of Croagh Patrick on the last Sunday in July. A number of fairs are also believed to be survivals of Lughnasadh, for example the Puck Fair. Since the latter twentieth century, Celtic neopagans have observed Lughnasadh, or something based on it, as a religious holiday. In some places, elements of the festival have been revived as a cultural event.

Etymology

In Old Irish (or Old Gaelic), the name was Lugnasad. This is a combination of Lug (the god Lugh) and násad (an assembly).[1] Later spellings include Luġnasaḋ, Lughnasadh, and Lughnasa.

In Modern Irish (Gaeilge), the spelling is Lúnasa, which is also the name for the month of August. In Modern Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), the festival and the month are both called Lùnastal.[2] In Manx (Gaelg), the festival and the month are both called Luanistyn.

In Welsh (Cymraeg), the day is known as Calan Awst, originally a Latin term,[3] the Calends of August in English.[1]

History

Lughnasadh was one of the four main festivals of the medieval Celtic calendar: Imbolc at the beginning of February, Beltane on the first of May, Lughnasadh in August, and Samhain in October. Lughnasadh marked the beginning of the harvest season, the ripening of first fruits, and was traditionally a time of community gatherings, market festivals, horse races, and reunions with distant family and friends.

In Irish mythology, the Lughnasadh festival is said to have been begun by the god Lugh (modern spelling: Lú) as a funeral feast and athletic competition (see funeral games) in commemoration of his mother (or foster-mother) Tailtiu, who was said to have died of exhaustion after clearing the plains of Ireland for agriculture.[4] The funeral games in her honor were called the Óenach Tailten or Áenach Tailten (modern spelling: Aonach Tailteann) and were held at Tailtin in what is now County Meath. The Óenach Tailten was similar to the Ancient Olympic Games and included ritual athletic and sporting contests. The event also involved trading, the drawing-up of contracts, and matchmaking.[4] At Tailtin, trial marriages were conducted, whereby young couples joined hands through a hole in a wooden door. The trial marriage lasted a year and a day, at which time the marriage could be made permanent or broken without consequences.[4][5][6][7]

A similar Lughnasadh festival, the Óenach Carmain, was held in what is now County Kildare. Carman is also believed to have been a goddess, perhaps one with a similar tale as Tailtiu.[3] After the ninth century the Óenach Tailten was celebrated irregularly and it gradually died out.[8] It was revived for a period in the twentieth century as the Tailteann Games.[5][3]

Folklorist Máire MacNeill researched historic accounts and earlier medieval writings about Lughnasadh, and concluded that the ancient festival on August 1st involved the following:

[A] solemn cutting of the first of the corn of which an offering would be made to the deity by bringing it up to a high place and burying it; a meal of the new food and of bilberries of which everyone must partake; a sacrifice of a sacred bull, a feast of its flesh, with some ceremony involving its hide, and its replacement by a young bull; a ritual dance-play perhaps telling of a struggle for a goddess and a ritual fight; an installation of a head on top of the hill and a triumphing over it by an actor impersonating Lugh; another play representing the confinement by Lugh of the monster blight or famine; a three-day celebration presided over by the brilliant young god or his human representative. Finally, a ceremony indicating that the interregnum was over, and the chief god in his right place again.[9]

Historic customs

Many of Ireland's prominent mountains and hills were climbed at Lughnasadh into the modern era. Over time, this custom was Christianized and some of the treks were re-cast as Christian pilgrimages. The most well-known is Reek Sunday—the yearly pilgrimage to the top of Croagh Patrick in County Mayo in late July.[10] As with the other Gaelic seasonal festivals, feasting was part of the celebrations.[11] Bilberries were gathered on the hills and mountains and were eaten on the spot or saved to make pies and wine.[12] In the Scottish Highlands, people made a special cake called the lunastain, which was also called luinean when given to a man and luineag when given to a woman. This may have originated as an offering to the gods.[13]

Another custom that Lughnasadh shared with Imbolc and Bealtaine was visiting holy wells. Visitors to holy wells would pray for health while walking sunwise around the well. They would then leave offerings; typically coins or clooties (see clootie well).[14] Although bonfires were lit at some of the open-air gatherings in Ireland, they were rare and incidental to the celebrations.[15]

Among the Irish, Lughnasadh was a favored time for handfastings - trial marriages that would generally last a year and a day, with the option of ending the contract before the new year, or later formalizing it as a more permanent marriage.[6][7][5]

Modern customs

In Ireland, some of the mountain pilgrimages have survived. By far the most popular is the Reek Sunday pilgrimage at Croagh Patrick, which attracts tens of thousands of pilgrims each year. The Catholic Church in Ireland established the custom of blessing fields at Lughnasadh.

The Puck Fair is held each year in early August in the town of Killorglin, County Kerry. It has been traced as far back as the 16th century but is believed to be a survival of a Lughnasadh festival. At the beginning of the three-day festival, a wild goat is brought into the town and crowned 'king', while a local girl is crowned 'queen'. The festival includes traditional music and dancing, a parade, arts and crafts workshops, a horse and cattle fair, and a market. It draws a great number of tourists each year.

In recent years, other towns in Ireland have begun holding yearly Lughnasa Festivals and Lughnasa Fairs. Like the Puck Fair, these often include traditional music and dancing, arts and crafts workshops, traditional storytelling, and markets. Such festivals have been held in Gweedore,[16] Sligo,[17] Brandon,[18] Rathangan[19] and a number of other places. Craggaunowen, an open-air museum in County Clare, hosts a yearly Lughnasa Festival at which historical re-enactors demonstrate elements of daily life in Gaelic Ireland. It includes displays of replica clothing, artefacts, weapons and jewellery.[20] A similar event has been held each year at Carrickfergus Castle in County Antrim.[21] In 2011, RTÉ aired a live television program from Craggaunowen at Lughnasa, called Lughnasa Live.[22]

In the Irish diaspora, survivals of the Lughnasadh festivities are often seen by some families still choosing August as the traditional time for family reunions and parties, though due to modern work schedules these events have sometimes been moved to adjacent secular holidays, such as the Fourth of July in the United States.[5][6]

The festival is referenced in Brian Friel's play Dancing at Lughnasa (1990), which was made into a film of the same name.

On mainland Europe and in Ireland many people continue to celebrate the holiday with bonfires and dancing. The Christian church has established the ritual of blessing the fields on this day. In the Irish diaspora, survivals of the Lá Lúnasa festivities are often seen by some families still choosing August as the traditional time for family reunions and parties, though due to modern work schedules these events have sometimes been moved to adjacent secular holidays, such as the Fourth of July in the United States.[6][5]

On August 1st, the national holiday of Switzerland, it is traditional to celebrate with bonfires. This practice may trace back to the Lughnasadh celebrations of the Helvetii, Celtic people of the Iron Age who lived in what is now Switzerland.

In Northern Italy, e.g. in Canzo, Lughnasadh traditions are still incorporated into modern 1 August festivities.

Lammas

In some English-speaking countries in the Northern Hemisphere, August 1 is Lammas Day (Anglo-Saxon hlaf-mas, "loaf-mass"), the festival of the wheat harvest, and is the first harvest festival of the year. On this day it was customary to bring to church a loaf made from the new crop, which began to be harvested at Lammastide. The loaf was blessed, and in Anglo-Saxon England it might be employed afterwards to work magic:[23] a book of Anglo-Saxon charms directed that the lammas bread be broken into four bits, which were to be placed at the four corners of the barn, to protect the garnered grain. In many parts of England, tenants were bound to present freshly harvested wheat to their landlords on or before the first day of August. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, where it is referred to regularly, it is called "the feast of first fruits". The blessing of first fruits was performed annually in both the Eastern and Western Churches on the first or the sixth of August (the latter being the feast of the Transfiguration of Christ).

Lammas coincides with the feast of St. Peter in Chains, commemorating St. Peter's miraculous deliverance from prison.

History

In medieval times the feast was sometimes known in England and Scotland as the "Gule of August",[24] but the meaning of "gule" is unclear. Ronald Hutton suggests[25] following the 18th-century Welsh clergyman antiquary John Pettingall[26] that it is merely an Anglicisation of Gŵyl Awst, the Welsh name of the "feast of August". OED and most etymological dictionaries give it a more circuitous origin similar to gullet; from O.Fr. goulet, dim. of goule, "throat, neck," from L. gula "throat,".

Several antiquaries beginning with John Brady[27] offered a back-construction to its being originally known as Lamb-mass, under the undocumented supposition that tenants of the Cathedral of York, dedicated to St. Peter ad Vincula, of which this is the feast, would have been required to bring a live lamb to the church,[28] or, with John Skinner, "because Lambs then grew out of season." This is a folk etymology, of which OED notes that it was "subsequently felt as if from LAMB + MASS".

For many villeins, the wheat must have run low in the days before Lammas, and the new harvest began a season of plenty, of hard work and company in the fields, reaping in teams.[29] Thus there was a spirit of celebratory play.

In the medieval agricultural year, Lammas also marked the end of the hay harvest that had begun after Midsummer. At the end of hay-making a sheep would be loosed in the meadow among the mowers, for him to keep who could catch it.[30]

In Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet (1.3.19) it is observed of Juliet, "Come Lammas Eve at night shall she [Juliet] be fourteen." Since Juliet was born Lammas eve, she came before the harvest festival, which is significant since her life ended before she could reap what she had sown and enjoy the bounty of the harvest, in this case full consummation and enjoyment of her love with Romeo.

Another well-known cultural reference is the opening of The Battle of Otterburn: "It fell about the Lammas tide when the muir-men win their hay".

William Hone speaks in The Every-Day Book (1838) of a later festive Lammas day sport common among Scottish farmers near Edinburgh. He says that they "build towers...leaving a hole for a flag-pole in the centre so that they may raise their colours." When the flags over the many peat-constructed towers were raised, farmers would go to others' towers and attempt to "level them to the ground." A successful attempt would bring great praise. However, people were allowed to defend their towers, and so everyone was provided with a "tooting-horn" to alert nearby country folk of the impending attack and the battle would turn into a "brawl." According to Hone, more than four people had died at this festival and many more were injured. At the day's end, races were held, with prizes given to the townspeople.

Lammas is one of the Scottish quarter days.

Revival

Neo-Paganism

Lughnasadh and Lughnasadh-based festivals are held by some Neopagans, especially Celtic Neopagans. However, their Lughnasadh celebrations can be very different despite the shared name. Some try to emulate the historic festival as much as possible,[31] while others base their celebrations on many sources, the Gaelic festival being only one of them.[32]

Neopagans usually celebrate Lughnasadh on July 31 – August 1 in the Northern Hemisphere and January 31 – February 1 in the Southern Hemisphere, beginning and ending at sunset.[33][34] Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the summer solstice and autumn equinox (or the full moon nearest this point).[35]

Wicca

In Wicca, Lughnasadh is one of the eight "sabbats" or solar festivals in the Wiccan Wheel of the Year, following Midsummer and preceding Mabon. Wiccans use the names "Lughnasadh" or "Lammas" for the first of their autumn harvest festivals, the other two being the Autumn equinox (or Mabon) and Samhain. Lughnasadh is seen as one of the two most auspicious times for handfasting, the other being at Beltane.[36]

Some Wiccans mark the holiday by baking a figure of the "corn god" in bread, and then symbolically sacrificing and eating it.[33]

Celtic Reconstructionism

In Celtic Reconstructionism Lá Lúnasa is seen as a time to give thanks to the spirits and deities for the beginning of the harvest season, and to propitiate them with offerings and prayers to not harm the still-ripening crops. The god Lugh is honored by many at this time, as he is a deity of storms and lightning, especially the storms of late summer. However, gentle rain on the day of the festival is seen as his presence and his bestowing of blessings. Many Celtic Reconstructionists also honor the goddess Tailitu on this day, and may seek to keep the Cailleachan ("Storm Hags") from damaging the crops, much in the way appeals are made to Lugh.[6][37][5]

Celtic Reconstructionists who follow Gaelic traditions tend to celebrate Lughnasadh at the time of "first fruits", or on the full moon nearest this time. In the Northeastern United States, this is often the time of the blueberry harvest, while in the Pacific Northwest the blackberries are often the festival fruit.[6]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Patrick S. Dinneen, Irish English Dictionary (Nabu Press, 2010).

- ↑ Alexander MacBain, Etymological Dictionary of Scottish-Gaelic (New York, NY: Hippocrene Books, 1998, ISBN 978-0781806329).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 James MacKillop, Dictionary of Celtic Mythology (Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0192801203).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Patricia Monaghan, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore (Checkmark Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0816075560).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 F. Marian McNeill, Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Vols. 1-4 (Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990, ISBN 978-0948474040).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Kevin Danaher, The Year in Ireland (Dublin: Mercier, 1972, ISBN 978-1856350938).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nora Chadwick, The Celts (Penguin Books, 1971, ISBN 978-0140212112).

- ↑ John Thomas Koch, (ed.), Celtic Culture : A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2005, ISBN 978-1851094400).

- ↑ Máire MacNeill, The Festival of Lughnasa (Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0906426104).

- ↑ Monaghan, p.104

- ↑ Monaghan, p.180

- ↑ Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing, 2004. p.45

- ↑ Monaghan, p.299

- ↑ Monaghan, p.41

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald. Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press, 1996. pp.327–330

- ↑ Loinneog Lúnasa. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ Sligo Lúnasa Festival. Sligo Tourism. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ Festival of Lughnasa – Cloghane & Brandon. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ Rathangan Lughnasa Festival. Kildare.tv. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ Lughnasa Festival at Craggaunowen. Shannon Heritage. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ "Lughnasa Fair returns to Carrickfergus Castle". Carrickfergus Advertiser, 25 July 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ RTÉ Television – Lughnasa Live. RTÉ.ie. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ T.C. Cokayne, ed. Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcarft (Rolls Series) vol. III:291, noted by George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991:371.

- ↑ J.P. Bacon Phillips, inquiring the significance of "gule", "Lammas-Day and the Gule of August", Notes and Queries, 2 August 1930:83.

- ↑ Hutton, The Stations of the Sun, Oxford 1996.

- ↑ Pettingall, in Archaeologia or, Miscellaneous tracts, relating to antiquity..., (Society of Antiquaries of London) 2:67.

- ↑ Brady, Clavis Calendaris, 1812, etc. s.v. "Lammas-Day".

- ↑ Reported without comment in John Brand, Henry Ellis, J.O. Halliwell-Phillips, Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, new ed. 1899: vol. I, s.v. "Lammas".

- ↑ Noted by Homans 1991:371.

- ↑ Homans 1991:371.

- ↑ Eugene V. Gallagher and W. Michael Ashcraft (eds.), Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0275987121).

- ↑ Margot Adler, Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0807032374).

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Starhawk, The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (San Francisco, CA: Harper, 1989, ISBN 978-0062508140).

- ↑ Murphy Pizza and James R. Lewis (eds.), Handbook of Contemporary Paganism (Brill Academic Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-9004163737).

- ↑ Seasons Archaeoastronomy.com. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ↑ Janet Farrar and Stewart Farrar, Eight Sabbats for Witches (Phoenix Publishing, 1988, ISBN 978-0919345263).

- ↑ Isaac Bonewits, Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism (Citadel Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0806527109).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0807032374

- Bonewits, Isaac. Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. Citadel Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0806527109

- Cabot, Laurie, and Jean Mills. Celebrate the Earth: A Year of Holidays in the Pagan Tradition. New York, NY: Dell Publisching, 1994. ISBN 978-0385309202

- Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica. Lindisfarne Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0940262508

- Danaher, Kevin. The Year in Ireland. Dublin: Mercier, 1972. ISBN 978-1856350938

- Dinneen, Patrick S. Irish English Dictionary. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1175212382

- Farrar, Janet, and Stewart Farrar. Eight Sabbats for Witches. Phoenix Publishing, 1988. ISBN 978-0919345263

- Gallagher, Eugene V., and W. Michael Ashcraft (eds.). Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0275987121

- Hamilton, Claire. Celtic Book of Seasonal Meditations: Celebrate the Traditions of the Ancient Celts. York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2003. ISBN 978-1590030554

- Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Wiley-Blackwell, 1993. ISBN 978-0631189466

- Hutton, Ronald. The Stations of the Sun. Oxford, 2001. ISBN 978-0192854483

- Koch, John Thomas (ed.). Celtic Culture : A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 978-1851094400

- MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0192801203

- MacBain, Alexander. Etymological Dictionary of Scottish-Gaelic. New York, NY: Hippocrene Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0781806329

- McNeill, F. Marian. Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Vols. 1-4. Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990. ISBN 978-0948474040

- MacNeill, Máire. The Festival of Lughnasa. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0906426104

- Melia, Daniel F. "The Grande Troménie at Locronan: A Major Breton Lughnasa Celebration" The Journal of American Folklore 91(359) (January 1978): 528-542.

- Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Checkmark Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0816075560

- Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. San Francisco, CA: Harper, 1989. ISBN 978-0062508140

- 'Publications of the Scottish Historical Society' 1964

External links

All links retrieved

- Lammas, Lughnasadh MYTH*ING LINKS

- Lammas (also called Lughnasadh) BBC

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.