Samhain

| Samhain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Neopagan celebration of Samhain | |

| Observed by | Gaels (Irish people, Scottish people), Neopagans (Wiccans, Celtic Reconstructionists) |

| Type | Festival of the Dead |

| Begins | Northern Hemisphere: Evening of October 31 Southern Hemisphere: Evening of April 30 |

| Ends | Northern Hemisphere: November 1 or November 11 Southern Hemisphere: May 1 |

| Celebrations | Traditional first day of winter in Ireland |

| Related to | Hallowe'en, All Saints Day, All Souls Day |

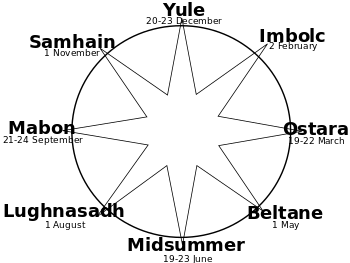

Samhain (pronounced /ËsÉËwÉȘn/ SAH-win or /ËsaÊ.ÉȘn/ SOW-in in English; from Irish samhain, Scottish samhuinn, Old Irish samain) is a Gaelic festival marking the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter or the "darker half" of the year. It is celebrated from sunset on October 31 to sunset on November 1. Along with Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh it makes up the four Gaelic seasonal festivals. It was traditionally observed in Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. Kindred festivals were held at the same time of year in other Celtic lands; for example the Brythonic Calan Gaeaf (in Wales), Kalan Gwav (in Cornwall) and Kalan Goañv (in Brittany). The Gaelic festival became associated with the Catholic All Souls' Day, and appears to have influenced the secular customs now connected with Halloween. In modern Ireland and Scotland, the name by which Halloween is known in the Gaelic language is still OĂche/Oidhche Shamhna.

Samhain (like Beltane) was seen as a liminal time, when the Aos SĂ (spirits or fairies) could more easily come into our world. It was believed that the Aos SĂ needed to be propitiated to ensure that the people and their livestock survived the winter and so offerings of food and drink were left for them. The spirits of the dead were also thought to revisit their homes. Feasts were held, at which the spirits of the ancestors and dead kinfolk were invited to attend and a place set at the table for them.

Etymology

The term "Samhain" derives from the name of the month SAMON[IOS] in the ancient Celtic calendar, in particular the first three nights of this month when the festival marking the end of the summer season and the end of the harvest is held.

The Irish word Samhain is derived from the Old Irish samain, samuin, or samfuin, all referring to November 1 (latha na samna: 'samhain day'), and the festival and royal assembly held on that date in medieval Ireland (oenaig na samna: 'samhain assembly'). Also from the same source are the Scottish Gaelic Samhainn/Samhuinn and Manx Gaelic Sauin. These are also the names of November in each language, shortened from MĂ na Samhna (Irish), MĂŹ na Samhna (Scottish Gaelic) and Mee Houney (Manx). The night of October 31 (Halloween) is OĂche Shamhna (Irish), Oidhche Shamhna (Scottish Gaelic) and Oie Houney (Manx), all meaning "Samhain night." November 1, or the whole festival, may be called LĂĄ Samhna (Irish), LĂ Samhna (Scottish Gaelic) and Laa Houney (Manx), all meaning "Samhain day."

Coligny calendar

The Coligny calendar split the year into two-halves: the 'dark' half beginning with the month Samonios (the October/November lunation), and the 'light' half beginning with the month GIAMONIOS (the April/May lunation), which is related to the word for winter.

The entire year may have been considered as beginning with the 'dark' half. Samonios was the first month of the 'dark' half of the year, and the festival of Samhain was held during the "three nights of Samonios."[1] Thus, Samhain may have been a celebration marking the beginning of the Celtic year.[2][3][4]

The lunations marking the middle of each half-year may also have been marked by specific festivals. The Coligny calendar marks the mid-summer moon (Lughnasadh), but omits the mid-winter one (Imbolc). The seasons are not oriented at the solar year, the solstice and equinox, so the mid-summer festival would fall considerably later than summer solstice, around August 1 (Lughnasadh). It appears that the calendar was designed to align the lunations with the agricultural cycle of vegetation, and that the exact astronomical position of the Sun at that time was considered less important.

History

Samhain is known to have pre-Christian roots. It was the name of the feis or festival marking the beginning of winter in Gaelic Ireland. It is attested in some of the earliest Old Irish literature, from the tenth century onward. It was one of four Celtic seasonal festivals: Samhain (~1 November), Imbolc (~1 February), Beltane (~1 May) and Lughnasadh (~1 August). Samhain and Beltane, at opposite sides of the year from each other, are thought to have been the most important. Sir James George Frazer wrote in The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion that May 1 and November 1 are of little importance to European crop-growers, but of great importance to herdsmen. It is at the beginning of summer that cattle is driven to the upland summer pastures and the beginning of winter that they are led back. Thus, Frazer suggested that halving the year at May 1 and November 1 dates from a time when the Celts were mainly a pastoral people, dependent on their herds.[5]

The Celts regarded winter, the season of cold and death, as the time of year ruled by the Cailleach, the old hag. Livestock were brought inside or slaughtered for food, and the harvest was gathered prior to Samhain. Anything remaining in the fields would be taken by the Cailleach, who would kill anything left alive. It was a time to reflect on the past and prepare for the future, to rest and conserve energy in anticipation of the spring when the crops and animals would have new life and the people would be reinvigorated spiritually and physically.[6]

In medieval Ireland, Samhain became the principal festival, celebrated with a great assembly at the royal court in Tara, lasting for three days. It marked the end of the season for trade and warfare and was an ideal date for tribal gatherings. After being ritually started on the Hill of Tlachtga, a bonfire was set alight on the Hill of Tara, which served as a beacon, signaling to people gathered atop hills all across Ireland to light their ritual bonfires. These gatherings are a popular setting for early Irish tales.[7]

In Irish mythology

According to Irish mythology, Samhain (like Beltane) was a time when the doorways to the Otherworld opened, allowing the spirits and the dead to come into our world; but while Beltane was a summer festival for the living, Samhain "was essentially a festival for the dead."[8] The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn says that the sĂdhe (fairy mounds or portals to the Otherworld) "were always open at Samhain."[9]

Many important events in Irish mythology happen or begin on Samhain. The invasion of Ulster that makes up the main action of the TĂĄin BĂł CĂșailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley) begins on Samhain. As cattle-raiding typically was a summer activity, the invasion during this off-season surprised the Ulstermen. The Second Battle of Maighe Tuireadh also begins on Samhain.[8]

According to the Dindsenchas and Annals of the Four Masters, which were written by Christian monks, Samhain in ancient Ireland was associated with the god Crom Cruach. The texts claim that King Tigernmas (Tighearnmhas) made offerings to Crom Cruach each Samhain, sacrificing a first-born child by smashing their head against a stone idol of the god.[8] The Four Masters says that Tigernmas, with "three-fourths of the men of Ireland about him" died while worshiping Crom Cruach at Magh Slécht on Samhain.[10] Other texts say that Irish kings Diarmait mac Cerbaill and Muirchertach mac Ercae both die a threefold death on Samhain, which may be linked to human sacrifice.[11]

The Ulster Cycle contains many references to Samhain. In the tenth-century Tochmarc Emire (the Wooing of Emer), Samhain is the first of the four "quarter days" of the year mentioned by the heroine Emer.[7] The twelfth century tales Mesca Ulad and Serglige Con Culainn begin at Samhain. In Serglige Con Culainn, it is said that the festival of the Ulaidh at Samhain lasted a week: Samhain itself, and the three days before and after. They would gather on the Plain of Muirthemni where there would be meetings, games, and feasting.[7] In Aislinge Ăengusa (the Dream of Ăengus) it is when he and his bride-to-be switch from bird to human form, and in Tochmarc ĂtaĂne (the Wooing of ĂtaĂn) is the day on which Ăengus claims the kingship of BrĂș na BĂłinne.[11] In Echtra NeraĂ (the Adventure of Nera), one Nera from Connacht undergoes a test of bravery on Samhain.[8]

In the Boyhood Deeds of Fionn, the young Fionn Mac Cumhaill visits Tara where Aillen the Burner puts everyone to sleep at Samhain and burns the place. However, Fionn is able to stay awake and slays Aillen, and is made the head of the fianna.

Several sites in Ireland are especially linked to Samhain. A host of otherworldly beings was said to emerge from Oweynagat ("cave of the cats"), near Rathcroghan in County Roscommon, each Samhain.[12] The Hill of Ward (or Tlachta) in County Meath is thought to have been the site of a great Samhain gathering and bonfire.[8]

Historic customs

Samhain was one of the four main festivals of the Gaelic calendar, marking the end of the harvest and beginning of winter. Traditionally, Samhain was a time to take stock of the herds and food supplies. Cattle were brought down to the winter pastures after six months in the higher summer pastures. It was also the time to choose which animals would need to be slaughtered for the winter. This custom is still observed by many who farm and raise livestock.[13][4] because it is when meat will keep since the freeze has come and also since summer grass is gone and free foraging is no longer possible.

As at Beltane, bonfires were lit on hilltops at Samhain. However, by the modern era, they only seem to have been common along Scotland's Highland Line, on the Isle of Man, in north and mid Wales, and in parts of Ulster heavily settled by Scots.[7] It has been suggested that the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic â they mimicked the Sun, helping the "powers of growth" and holding back the decay and darkness of winter. They may also have served to symbolically "burn up and destroy all harmful influences".[5] Accounts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries suggest that the fires (as well as their smoke and ashes) were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.[7] Sometimes, two bonfires would be built side by side, and the people â sometimes with their livestock â would walk between them as a cleansing ritual. The bones of slaughtered cattle were said to have been cast upon bonfires.

People took flames from the bonfire back to their homes. In northeastern Scotland, they carried burning fir around their fields to protect them, and on South Uist they did likewise with burning turf.[7] In some places, people doused their hearth fires on Samhain night. Each family then solemnly re-lit its hearth from the communal bonfire, thus bonding the families of the village together.[13][4]

The bonfires were also used in divination rituals. In the late eighteenth century, in Ochtertyre, a ring of stones was laid round the fire to represent each person. Everyone then ran round it with a torch, "exulting." In the morning, the stones were examined and if any was mislaid it was said that the person for whom it was set would not live out the year. A similar custom was observed in north Wales[7] and in Brittany. Frazer suggested that this may come from "an older custom of actually burning them" (human sacrifice) or may have always been symbolic.[5]

Divination has likely been a part of the festival since ancient times,[8] and it has survived in some rural areas.[3] At household festivities throughout the Gaelic regions and Wales, there were many rituals intended to divine the future of those gathered, especially with regard to death and marriage.[8][7] Seasonal foods such as apples and nuts were often used in these rituals. Apples were peeled, the peel tossed over the shoulder, and its shape examined to see if it formed the first letter of the future spouse's name.[3] Nuts were roasted on the hearth and their behavior interpreted â if the nuts stayed together, so would the couple. Egg whites were dropped in water, and the shapes foretold the number of future children. Children would also chase crows and divine some of these things from the number of birds or the direction they flew.[13][4]

Samhain was seen as a liminal time, when spirits or fairies (the aos sĂ) could more easily come into our world. At Samhain, it was believed that the aos sĂ needed to be propitiated to ensure that the people and their livestock survived the harsh winter. Thus, offerings of food and drink were left for the aos sĂ.[14][15][4] Portions of the crops might also be left in the ground for them.[3] People also took special care not to offend the aos sĂ and sought to ward-off any who were out to cause mischief. They stayed near to home or, if forced to walk in the darkness, turned their clothing inside-out or carried iron or salt to keep them at bay.[8]

The souls of the dead were also thought to revisit their homes. Places were set at the dinner table or by the fire to welcome them.[4][13] The souls of thankful kin could return to bestow blessings just as easily as that of a murdered person could return to wreak revenge.[8] It is still the custom in some areas to set a place for the dead at the Samhain feast, and to tell tales of the ancestors on that night.[3][4][13]

Mumming and guising was a part of Samhain from at least the sixteenth century and was recorded in parts of Ireland, Scotland, Mann, and Wales. This involved people going from house to house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting songs or verses in exchange for food. The costumes may have been a way of imitating, or disguising oneself from, the aos sĂ.[7] McNeill suggests that the ancient festival included people in masks or costumes representing these spirits and that the modern custom came from this.[16]

In Ireland, costumes were sometimes worn by those who went about before nightfall collecting for a Samhain feast.[7] In parts of southern Ireland during the nineteenth century, the guisers included a hobby horse known as the LĂĄir BhĂĄn (white mare). A man covered in a white sheet and carrying a decorated horse skull (representing the LĂĄir BhĂĄn) would lead a group of youths, blowing on cow horns, from farm to farm. At each they recited verses, some of which "savoured strongly of paganism," and the farmer was expected to donate food. This is similar to the Mari Lwyd (grey mare) procession in Wales.

In Scotland, young men went house-to-house with masked, veiled, painted, or blackened faces,[17] often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed.[7] It is suggested that the blackened faces comes from using the bonfire's ashes for protection.[16] Elsewhere in Europe, costumes, mumming and hobby horses were part of other yearly festivals. However, in the Celtic-speaking regions they were "particularly appropriate to a night upon which supernatural beings were said to be abroad and could be imitated or warded off by human wanderers".[7]

Playing pranks at Samhain is recorded in the Scottish Highlands as far back as 1736 and was also common in Ireland, which led to Samhain being nicknamed "Mischief Night" in some parts: "When imitating malignant spirits it was a very short step from guising to playing pranks."[7] Wearing costumes at Halloween spread to England in the twentieth century, as did the custom of playing pranks, though there had been mumming at other festivals. "Trick-or-treating" may have come from the custom of going door-to-door collecting food for Samhain feasts, fuel for Samhain bonfires, and/or offerings for the aos sĂ.

The "traditional illumination for guisers or pranksters abroad on the night in some places was provided by turnips or mangel wurzels, hollowed out to act as lanterns and often carved with grotesque faces to represent spirits or goblins."[7] They may have also been used to protect oneself from harmful spirits.[17] These turnip lanterns were also found in Somerset in England. In the twentieth century they spread to other parts of England and became generally known as jack-o'-lanterns.

Celtic Revival

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Celtic Revival, there was an upswell of interest in Samhain and the other Celtic festivals. The Tochmarc Emire, written in the Middle Ages, reckoned the year around the four festivals at the beginning of each season, and put Samhain at the beginning of those.

In the Hibbert Lectures in 1886, Welsh scholar Sir John Rhys set out the the idea that Samhain was the "Celtic New Year."[18] This he inferred from folkore in Wales and Ireland, and visit to the Isle of Man where he found that the Manx sometimes called October 31st "New Year's Night" or Hog-unnaa. Rhys' theory was popularized by Sir James George Frazer, though at times he did acknowledge that the evidence is inconclusive. Since then, Samhain has been seen as the Celtic New Year and an ancient festival of the dead.

Related festivals

In the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages, Samhain is known as the "calends of winter." The Brythonic lands of Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany held festivals on October 31st similar to the Gaelic one. In Wales it is Calan Gaeaf, in Cornwall it is Allantide or Kalan Gwav and in Brittany it is Kalan Goañv.[11]

Brittany

In parts of western Brittany, Samhain is still heralded by the baking of kornigou, cakes baked in the shape of antlers to commemorate the god of winter shedding his 'cuckold' horns as he returns to his kingdom in the Otherworld.

With Christianization, the festival in November became All Hallows' Day on November 1st, followed by All Souls' Day on November 2nd. Over time, the night of October 31st came to be called All Hallow's Eve, and the remnants festival dedicated to the dead eventually morphed into the secular holiday known as Halloween.

Wales

The Welsh equivalent of this holiday is called Galan Gaeaf. As with Samhain, this marks the beginning of the dark half of the year, or winter, and it officially begins at sunset on October 31st. The night before is Nos Calan Gaeaf, an Ysbrydnos when spirits are abroad. People avoid churchyards, stiles, and crossroads, since spirits are thought to gather there.

Isle of Man

Hop-tu-Naa is a Celtic festival celebrated in the Isle of Man on 31 October. Predating Halloween, it is the celebration of the original New Year's Eve (Oie Houney). The term is Manx Gaelic in origin, deriving from Shogh taân Oie, meaning "this is the night." Hogmanay, which is the Scottish New Year, comes from the same root.

For Hop-tu-Naa children dress up as scary beings and go from house to house carrying turnips, with the hope of being given treats.

All Saints' Day

The Roman Catholic holy day of All Saints (or All Hallows) was introduced in the year 609, but was originally celebrated on May 13. In 835, Louis the Pious switched it to November 1 in the Carolingian Empire, at the behest of Pope Gregory IV. However, from the testimony of Pseudo-Bede, it is known that churches in what are now England and Germany were already celebrating All Saints on November 1 at the beginning of the eighth century Thus, Louis merely made official the custom of celebrating it on November 1. James Frazer suggests that November 1 was chosen because it was the date of the Celtic festival of the dead (Samhain) â the Celts had influenced their English neighbors, and English missionaries had influenced the Germans. However, Ronald Hutton points out that, according to Ăengus of Tallaght (d. ca. 824), the seventh/eighth century church in Ireland celebrated All Saints on April 20th. He suggests that the November 1st date was a Germanic rather than a Celtic idea.[7]

Over time, the night of October 31st came to be called All Hallows' Eve (or All Hallows' Even). Samhain influenced All Hallows' Eve and vice-versa, and the two eventually morphed into the secular holiday known as Halloween.

Neopaganism

Samhain is also the name of a festival in various currents of Neopaganism inspired by Gaelic tradition.[3][4][19] Samhain is observed by various Neopagans in various ways. As forms of Neopaganism can differ widely in both their origins and practices, these representations can vary considerably despite the shared name. Some Neopagans have elaborate rituals to honor the dead, and the deities who are associated with the dead in their particular culture or tradition. Some celebrate in a manner as close as possible to how the Ancient Celts and Living Celtic cultures have maintained the traditions, while others observe the holiday with rituals culled from numerous other unrelated sources, Celtic culture being only one of the sources used.[20][19]

Neopagans usually celebrate Samhain on October 31 â November 1 in the Northern Hemisphere and April 30 â May 1 in the Southern Hemisphere, beginning and ending at sundown.[21] Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the autumn equinox and winter solstice (or the full moon nearest this point).

Celtic Reconstructionism

Celtic Reconstructionist Pagans tend to celebrate Samhain on the date of first frost, or when the last of the harvest is in and the ground is dry enough to have a bonfire. Like other Reconstructionist traditions, Celtic Reconstructionists place emphasis on historical accuracy, and base their celebrations and rituals on traditional lore from the living Celtic cultures, as well as research into the older beliefs of the polytheistic Celts. At bonfire rituals, some observe the old tradition of building two bonfires, which celebrants and livestock then walk or dance between as a ritual of purification.[22][4][13]

According to Celtic lore, Samhain is a time when the boundaries between the world of the living and the world of the dead become thinner, allowing spirits and other supernatural entities to pass between the worlds to socialize with humans. It is the time of the year when ancestors and other departed souls are especially honored. Though Celtic Reconstructionists make offerings to the spirits at all times of the year, Samhain in particular is a time when more elaborate offerings are made to specific ancestors. Often a meal will be prepared of favorite foods of the family's and community's beloved dead, a place set for them at the table, and traditional songs, poetry and dances performed to entertain them. A door or window may be opened to the west and the beloved dead specifically invited to attend. Many leave a candle or other light burning in a western window to guide the dead home. Divination for the coming year is often done, whether in all solemnity or as games for the children. The more mystically inclined may also see this as a time for deeply communing with the deities, especially those whom the lore mentions as being particularly connected with this festival.[22][4][13]

Wicca

Samhain is one of the eight annual festivals, often referred to as 'Sabbats', observed as part of the Wiccan Wheel of the Year. It is considered by most Wiccans to be the most important of the four 'greater Sabbats'. It is generally observed on October 31st in the Northern Hemisphere, starting at sundown. Samhain is considered by some Wiccans as a time to celebrate the lives of those who have passed on, because at Samhain the veil between this world and the afterlife is at its thinnest point of the whole year, making it easier to communicate with those who have left this world. Festivals often involve paying respect to ancestors, family members, elders of the faith, friends, pets, and other loved ones who have died. In some rituals the spirits of the departed are invited to attend the festivities.

Samhain is seen as a festival of darkness, which is balanced at the opposite point of the wheel by the spring festival of Beltane, which Wiccans celebrate as a festival of light and fertility.[23]

Notes

- â The Coligny Tablet Roman Britain. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- â Nora Chadwick, The Celts (London: Penguin, 1970, ISBN 0140212116).

- â 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Kevin Danaher, The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs Dublin: Mercier, 1972, ISBN 1856350932).

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 F. Marian McNeill, Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals - Hallowe'en to Yule Vol. 3 (Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990, ISBN 0948474041).

- â 5.0 5.1 5.2 James George Frazer, The Golden Bough (Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1998, ISBN 978-1853263101).

- â Claire Hamilton, Celtic Book of Seasonal Meditations: Celebrate the Traditions of the Ancient Celts (York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2003, ISBN 978-1590030554), 2-6.

- â 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0192854483).

- â 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 Patricia Monaghan, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore (Checkmark Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0816075560).

- â John T. Koch, Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2006, ISBN 978-1851094400), 388.

- â Annals of the Four Masters: Part 6 Corpus of Electronic Texts. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- â 11.0 11.1 11.2 John T. Koch, The Celts: History, Life, and Culture (ABC-CLIO, 2012, ISBN 978-1598849646), 690.

- â Andy Halpin and Conor Newman, Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0192880574), 236.

- â 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Robert O'Driscoll (ed.), The Celtic Consciousness (New York, NY: George Braziller, 1985, ISBN 0807611360).

- â Sharon Paice MacLeod, Celtic Myth and Religion (McFarland, 2011, ISBN 978-0786464760).

- â Walter Evans-Wentz The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries(New York, NY: Citadel, 1990, ISBN 0806511605).

- â 16.0 16.1 F. Marian McNeill, Hallowe'en: Its Origin, Rites and Ceremonies in the Scottish Tradition (Albyn Press, 1970, ISBN 978-0284985378), 29â31.

- â 17.0 17.1 Bettina Arnold, Halloween Lecture: Halloween Customs in the Celtic World UWM Center for Celtic Studies Halloween Inaugural Celebration UWM Hefter Center, October 31, 2001. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- â John Rhys, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by Celtic Heathendom (Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-1419173264).

- â 19.0 19.1 Ronald Hutton, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993, ISBN 978-0631189466).

- â Margot Adler, Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0807032374).

- â Murphy Pizza and James R. Lewis (eds.), Handbook of Contemporary Paganism (Brill Academic Pub, 2009, ISBN 978-9004163737).

- â 22.0 22.1 Isaac Bonewits, Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism (New York, NY: Kensington Publishing Group, 2006, ISBN 978-0806527109).

- â Starhawk, The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (New York: Harper and Row, 1989, ISBN 978-0062516329).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0807032374

- Bonewits, Isaac. Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, NY: Citadel Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0806527109

- Cabot, Laurie, and Jean Mills. Celebrate the Earth: A Year of Holidays in the Pagan Tradition. New York, NY: Delta, 1994. ISBN 978-0385309202

- Campbell, John Gregorson, and Ronald Black. The Gaelic Otherworld. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd., 2005. ISBN 978-1841582078

- Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica. Lindisfarne Press, 1992. ISBN 0940262509

- Chadwick, Nora. The Celts. London: Penguin, 1970. ISBN 0140212116

- Danaher, Kevin. The Year in Ireland. Dublin: Mercier, 1972. ISBN 1856350932

- Evans-Wentz, Walter. The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries. New York, NY: Citadel, 1990. ISBN 0806511605

- Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough. Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1998. ISBN 978-1853263101

- Halpin, Andy, and Conor Newman. Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0192880574

- Hamilton, Claire. Celtic Book of Seasonal Meditations: Celebrate the Traditions of the Ancient Celts. York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2003. ISBN 978-1590030554

- Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford: Blackwell, 1993. ISBN 978-0631189466

- Hutton, Ronald. The Stations Of The Sun. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0192854483

- Koch, John T. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 978-1851094400

- Koch, John T. The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. ABC-CLIO, 2012. ISBN 978-1598849646

- MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0192801201

- MacLeod, Sharon Paice. Celtic Myth and Religion. McFarland, 2011. ISBN 978-0786464760

- McNeill, F. Marian. Hallowe'en: Its Origin, Rites and Ceremonies in the Scottish Tradition. Albyn Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0284985378

- McNeill, F. Marian. Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals - Hallowe'en to Yule Vol. 3. Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990. ISBN 0948474041

- Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Checkmark Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0816075560

- O'Driscoll, Robert (ed.). The Celtic Consciousness. New York, NY: George Braziller, 1985. ISBN 0807611360

- Pizza, Murphy, and James R. Lewis (eds.). Handbook of Contemporary Paganism. Brill Academic Pub, 2009. ISBN 978-9004163737

- Rhys, John. Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by Celtic Heathendom. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-1419173264

- Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1999. ISBN 978-0062516329

External links

All links retrieved September 20, 2023.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.