Difference between revisions of "Knossos" - New World Encyclopedia

(Images OK) |

(Approved) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

[[Category:Nations and places]] | [[Category:Nations and places]] | ||

| − | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Contracted}} | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Contracted}} |

[[Image:knossos_r5.jpg|thumb|right|200px|A portion of Arthur Evans' reconstruction of the Minoan palace at Knossos]] | [[Image:knossos_r5.jpg|thumb|right|200px|A portion of Arthur Evans' reconstruction of the Minoan palace at Knossos]] | ||

Revision as of 06:54, 25 November 2006

Knossos, also spelled Knossus, Cnossus, Gnossus (in traditional Greek Κνωσός, in Mycenaean Greek ko-no-so, and ku-ni-su in Minoan), is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete, possibly the ceremonial and political center of the Minoan culture. Minoan culture continues to hold many mysteries, including their script Linear A, but numerous examples of their art have been uncovered, preserved, and displayed to the public. Knossos is a popular tourist destination, as it is near the main city of Heraklion, and has been substantially if imaginatively "rebuilt," making the site accessible to the casual visitor in a way that a field of unmarked ruins is not. Thus, the beauty of this long-lost civilization, known to us as "Minoan," can still be experienced and appreciated, even if not in its original form.

Discovery

Knossos was discovered in 1878 by Minos Kalokairinos, a Cretan merchant and antiquarian. Kolokairinos himself conducted the first excavations which brought to light part of the magazines in the west wing of the palace and a section of the west facade. After Kalokairinos, several people attempted to continue the excavations, but it was not until March 16, 1900 that British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans was able to purchase the entire site and conduct massive excavations. Assisted by Duncan Mackenzie and the British School of Athens architect, Fyfe, Evans employed a large staff of excavators and by June of 1900 had uncovered a large portion of the palace.

History

One of the most unique features of the site is its mosaic of styles and inhabitation; natural disasters, such as fires and earthquakes, along with numerous occupations by different cultures, caused constant re-building and additions to the site. Knossos was most likely settled at some point before 7000 B.C.E., inhabited by the Minoans who, along with the Mycenaeans, are thought to be the descendents of early, Neolithic peoples from Asia Minor that settled in the region long before Greek civilization was a dominant power. The oldest buildings on Knossos are simple, stone structures from this time and, due to the constant re-construction of the time, not many survive.

The Minoan Period

Around 3000 B.C.E., during the early Bronze Age, architecture and culture started to show definitive Minoan characteristics. This was the time when the first palace of Knossos was built along with other impressive structures, such as villas, tombs, temples, and even a hospice.[1]

The palace was re-built in 1700 B.C.E. because of an earthquake, and was greatly expanded upon at that time. The design schematic it is based on is that of a central court in rectangular shape flanked by four wings, one on each side. The central court is aligned to North and South, and the labyrinth quality of the new design lends itself as the source of the myth of King Minos’ minotaur, which was housed in a labyrinth built by Daedalus. While there is no literal labyrinth at the site, the complexity of the layout (there are 1,300 rooms which connect to corridors of varying size and direction) adds to the enduring quality of the myth.

The palace was designed to take best advantage of natural lighting during the long days of the summer season. The suites of rooms were arranged around courtyards to provide more window openings, the doors were polythyra [2] ("multiple-door") to provide more door opening area, stairs[3] wound around the periphery of light wells, and corridors were open porticos [4] wherever possible. One cannot imagine that the palace shut down at night for lack of light, however. Minoan Crete had a long tradition of ceramic lamps,[5] which consisted of a reservoir of olive oil surrounded by niches for one or more wicks.

Some of the most significant aspects of the palace are the large store rooms located in the western wing of the palace, where pithoi (large clay vase) were used to store oils, grains, dried fish, beans, and olives. The Minoan column is also a striking characteristic for it differs sharply from the traditional Greek columns in that it was made of wood, painted red, and was also "inverted" in the sense that it was larger at the top than the bottom, the inversion of the Greek style.

Outside of the main palace, some of the other structures the Minoans were responsible for include a smaller palace dubbed the Little Palace, the Temple Tomb, in which one of the last Minoan Kings were buried, and what is referred to as the South Mansion, one of the larger private residences.[1] Scholars can only conjecture as to whether the palace's main role was religious, ceremonial, or administrative and whether it was the central palace of Minoan culture or shared an equal footing with other palaces of the time.

There is still much that is unknown about Minoan culture, particularly due to continuing inability to decipher their written language, called Linear A that was preserved on clay tablets. Archaeologists and historians know that at one point the Minoans played a pivotal role in the major sea trading routes with Egypt, but appeared to be less imperialistic than other regional powers of the time. They worshiped a fertility goddess, seemed to be actively engaged in rituals and sports, and from their art work revered nature. The Minoans excelled at art, especially with bronze, ivory, and stone sculptures depicting slender male and female figures in worship along with animals and god figures.

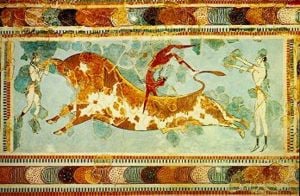

One of the more remarkable discoveries at Knossos was the extensive set of frescoes that decorated the plastered walls, one of the first examples of landscapes painted for their own sake, without enhancement by human figures for comparison.[6] All were very fragmentary and their reconstruction and placement in the rooms of the palace by the artist Piet de Jong is not without controversy. These sophisticated, colorful paintings portray a society who, in comparison to the roughly contemporaneous art of Middle and New Kingdom Egypt, are conspicuously non-militaristic. In addition to scenes of women and men linked to activities like fishing and flower gathering, the murals also portray athletic feats. The most notable of these is bull-vaulting, where a young man apparently leaps onto and over a charging bull's back. The question remains as to whether this activity was a ritual or a sport. Some have proposed that it was a sacrificial activity or early bullfighting. Indeed, many people have questioned if this activity is even possible. The most famous example is the Toreador Fresco, painted around 1550-1450 B.C.E. It is now located in the Archaeological Museum of Herakleion in Crete.

The Mycenaean Period

The decline of the Minoan civilization came during the rise of the Mycenaeans, one of the mainland Aegean civilizations. The Mycenaeans came to the island of Crete in the fifteenth century. They maintained the palace and the city, and detailed records, in the Mycenaean script known as Linear B, found in Knossos reveal Mycenaean control over much of Crete.

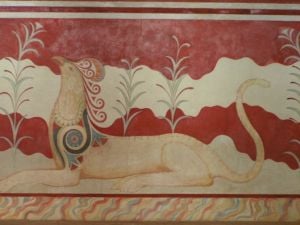

The centerpiece of the "Mycenaean" palace was the so-called Throne Room. This chamber has an alabaster "throne" built into the wall, facing a number of benches. The throne is flanked by mythological beasts such as griffins, which are thought to symbolize divinity, as seen on other media of iconography such as seal rings.

The throne is flanked by the Griffin Fresco, with two griffins couchant facing the throne on either side. Griffins also appear on seal rings, which, no matter what purposes the throne and throne room had, were used to stamp the identity of the bearer or his authority in pliable material, such as clay or wax.

The actual use of the Throne Room and the throne is unclear, but may well have been part of a ritual where it was imagined that a goddess appeared, or that a priestess dressed as a goddess. The actual use of the Room and the throne is unclear. The two main theories are:

- The seat of a priest-king or his consort, the queen. This is the older theory, originating with Arthur Evans. In that regard Matz[7] speaks of the "heraldic arrangement" of the griffins, meaning that they are more formal and monumental than previous Minoan decorative styles. In theory, the Mycenaean Greeks would have held court in this room, as they came to power in Knossos at about 1450 b.c.e..

- A room reserved for the supposed epiphany of a goddess,[8] who would have sat in the throne, either in effigy, or the person of a priestess, or in imagination only. In that case the griffins would have been purely a symbol of divinity rather than a heraldic motif.

This room has a lustral basin, originally thought to have had a ritual washing use, but the lack of drainage has more recently brought scholars to doubt this theory. In addition, the Mycenaeans also added defensive structures, cemeteries, and sanctuaries to Glaukos and Demeter to the surrounding town.[1]

The Mycenaeans not only occupied the structures of Knossos, they took over the wealth and regional trading role the Minoans had played, although they were not as successful as their forbearers. In 1200 B.C.E. the Mycenaean civilization collapsed.

Later Occupations

The Dorian invasion around 1200 B.C.E. not only led to the destruction of Mycenaean civilization, but left Knossos in the invader's hands for roughly 1100 years. In the first century B.C.E., Quintus Caecilius Metelus Cretieus of Rome captured Knossos, and Crete became a long standing colony of the Roman Empire. One of the most famous Roman additions is the Villa of Dionysos, a large, decorative structure that was most likely used for Dionysian festivals.

Reconstruction

By the fall of the Roman Empire, most of the original structures were buried and, or destroyed by natural and human means. When Arthur Evans came upon the site during the early twentieth century, it bore little resemblance to what it once was. Fascinated by antiquity, Evans conducted mass excavations until he believed he had unearthed enough of the ruined city to re-build it.

Evans' work has drawn criticism over the years, for without blue prints of any kind, he re-built structures by speculating on how they should have looked. One of the famous examples was a series of structures he took to be the base of the mythical labyrinth of King Minoa, creating a real labyrinth in the ruins, that may or may not have been such a structure. Evans also used modern building materials to complete the re-construction, thus mixing old technology with new. While the job was carried out with such precision that buildings appear authentic, which is good for tourism, critics argue that it does not accurately represent the original Knossos and that complete reconstruction of sites does not correspond to the ideals of preservation.

Today the site is maintained by the Hellenic Archaeological Service of the Ministry of Culture, and continues to be a place of study and preservation.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Knossos" Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

- ↑ photo of polythyra doors at Knossos

- ↑ photo of stairs at Knossos

- ↑ photo of porticos at Knossos

- ↑ photo of Minoan clay lamps

- ↑ “Aegean Civilization” Funk & Wagnalls Encyclopedia. 2006 World Almanac Education Group.

- ↑ Matz, Friedrich. 1962. The Art of Crete and Early Greece Greystone Press. ISBN 0442315252

- ↑ Peter Warren. 1988. Minoan Religion as Ritual Action. P. Astroms.

Sources

- Benton, Janetta Rebold and Robert DiYanni.Arts and Culture: An introduction to the Humanities, Volume 1. Prentice Hall. New Jersey, 1998. [Pages 64-70]

- Bourbon, F. Lost Civilizations Barnes and Noble, Inc. New York, 1998. [Pages 30-35]

External

- Hellenic Ministry of Culture

- British School at Athens Knossos Pages

- Aegean Prehistory Online at Dartmouth

- Knossos photo gallery

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.