Kaunda, Kenneth

| (46 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | + | {{epname|Kaunda, Kenneth}} | |

| − | {{ | + | {{Infobox_Officeholder|name=Kenneth Kaunda |

|nationality=Zambian | |nationality=Zambian | ||

| − | |image=Kenneth Kaunda.jpg | + | |image=Kenneth David Kaunda detail DF-SC-84-01864.jpg |

| − | |order=1st [[List of Presidents of Zambia|President of | + | |order=1st [[List of Presidents of Zambia|President of Zambia]] |

| − | |term_start=24 | + | |term_start=October 24, 1964 |

| − | |term_end=2 | + | |term_end=November 2, 1991 |

|predecessor= | |predecessor= | ||

|successor=[[Frederick Chiluba]] | |successor=[[Frederick Chiluba]] | ||

| − | |birth_date= | + | |order2=3rd [[Non-Aligned_Movement#Secretaries General|Secretary General of Non-Aligned Movement]] |

| + | |term_start2=September 10, 1970 | ||

| + | |term_end2=September 9, 1973 | ||

| + | |predecessor2=[[Gamal Abdel Nasser]] | ||

| + | |successor2=[[Houari Boumédienne]] | ||

| + | |birth_date={{Birth date and age|1924|4|28|mf=y}} | ||

|birth_place=[[Chinsali]], [[Northern Rhodesia]] | |birth_place=[[Chinsali]], [[Northern Rhodesia]] | ||

| − | | | + | |death_date= {{Death date and age|2021|6|17|1924|4|28|mf=yes}} |

| − | | | + | |death_place= [[Lusaka]], Zambia |

| − | |death_place= | ||

|spouse= Betty Kaunda | |spouse= Betty Kaunda | ||

|party=[[United National Independence Party]] | |party=[[United National Independence Party]] | ||

| Line 20: | Line 24: | ||

|religion= [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterian]] | |religion= [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterian]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

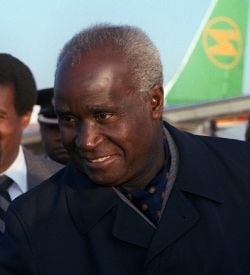

| − | '''Kenneth David Kaunda''', | + | '''Kenneth David Kaunda''', (April 28, 1924 - June 17, 2021) served as the first president of [[Zambia]], from 1964 to 1991. He played a major role in Zambia's independence movement which sought to free itself from [[Rhodesia]] and white minority rule. For his efforts, Kaunda suffered imprisonment and several confrontations with rival groups. |

| − | + | From the time he became President until his fall from power in 1991, Kaunda ruled under emergency powers, eventually banning all parties except his own [[United National Independence Party]]. While president, he dealt in autocratic fashion with severe [[economics|economic]] problems and challenges to his power, aligning his country against the West and instituting, with little success, [[socialism|socialist]] economic policies. Eventually because of mounting international pressure for more democracy in [[Africa]], and continuing economic problems, Kaunda was forced out of office in 1991. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Overall, however, Kaunda is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern Africa. | ||

| − | + | ==Early life== | |

| + | Kaunda was the youngest of eight children. He was born at Lubwa Mission in Chinsali, Northern Province of [[Northern Rhodesia]], now [[Zambia]]. His father was the Reverend David Kaunda, an ordained [[Church of Scotland]] missionary and teacher, who was born in [[Malawi]] and had moved to Chinsali to work at Lubwa Mission. He attended Munali Training Centre in [[Lusaka]] (August 1941–1943). | ||

| − | In | + | Kaunda was first a teacher at the Upper Primary School and boarding master at Lubwa and then headmaster at Lubwa from 1943 to 1945. He left Lubwa for Lusaka to become an instructor in the army, but was dismissed. He was for a time working at the Salisbury and Bindura Mine. In early 1948, he became a teacher in Mufulira for the United Missions to the Copperbelt (UMCB). He was then assistant at an African welfare center and Boarding Master of a mine school in Mufulira. In this period, he led a Pathfinder Scout group and was choirmaster at a Church of Central Africa Congregation. He was also for a time vice-secretary of the Nchanga Branch of Congress. |

| − | + | Kaunda married Betty Banda in 1946, with whom he had eight children. She died on September 17, 2013, aged 87, while visiting one of their daughters in Harare, Zimbabwe. | |

| − | + | ==Independence struggle== | |

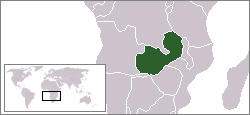

| + | [[Image:LocationZambia.png|thumb|400px|Location of Northern Rhodesia, today called Zambia]] | ||

| + | In 1949, Kaunda became an interpreter and adviser on African affairs to Sir Stewart Gore-Browne, a white settler and member of the Northern Rhodesian Legislative Council. Kaunda acquired knowledge of the colonial government and learned valuable political skills, both of which served him well when later that year he joined the [[African National Congress]] (ANC), the first major anti-colonial organization in Northern Rhodesia. In the early 1950s Kaunda became the ANC's secretary-general. He served as an organizing officer, a role that brought him into close contact with the movement's rank and file. Thus, when the leadership of the ANC clashed over strategy in 1958–1959, Kaunda carried a major part of the ANC operating structure into a new organization, the Zambia African National Congress. | ||

| − | + | In April 1949, Kaunda returned to Lubwa to become a part-time teacher, but resigned in 1951. In that year, he became an organizing secretary of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress for Northern Province, which included at that time Luapula Province. In November 1953 he moved to Lusaka to take up the post of Secretary General of the ANC, under the presidency of [[Harry Nkumbula]]. The combined efforts of Kaunda and Nkumbula at that time were unsuccessful in mobilizing African people against the white-dominated Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. In 1955, Kaunda and Nkumbula were imprisoned for two months at hard labor for distributing subversive literature. Such imprisonment and other forms of harassment were customary for African nationalist leaders. However, the experience of imprisonment had a radicalizing impact on Kaunda. | |

| − | + | Kaunda and Nkumbula drifted apart as Nkumbula became increasingly influenced by white liberals and was seen as being willing to compromise on the issue of majority rule. Nkumbula's allegedly autocratic leadership of the ANC eventually resulted in a complete split. Kaunda broke from the ANC and formed the Zambian African National Congress (ZANC) in October 1958. | |

| + | ZANC was banned in March 1959. In June 1959, Kaunda was sentenced to nine months' imprisonment, which he spent first in Lusaka, then in Salisbury (Harare). While Kaunda was in prison, Mainza Chona and other nationalists broke away from the ANC. In October 1959, Chona became the first president of the United National Independence Party (UNIP), the successor to ZANC. However, Chona did not see himself as the party's main founder. When Kaunda was released from prison in January 1960 he was elected President of UNIP. In July 1961, Kaunda organized a violent [[civil disobedience]] campaign in Northern Province which consisted of burning schools and blocking roads. | ||

| − | + | Kaunda ran as an UNIP candidate during the 1962 elections. This resulted in a UNIP–ANC Coalition Government, with Kaunda as Minister of Local Government and Social Welfare. In January 1964, UNIP won the general election under the new constitution, beating the ANC under Nkumbula. Kaunda was appointed prime minister. On October 24, 1964 he became the first president of independent [[Zambia]]. Simon Kapwepwe was appointed as the first Vice President. | |

| − | Kaunda | ||

| − | Kaunda | + | ==Presidency== |

| + | Kaunda ruled under a state of emergency from the time he became president until his fall from power in 1991. Becoming increasingly intolerant of opposition, Kaunda eventually banned all parties except his own UNIP, following violence during the 1968 elections. | ||

| − | == | + | ===Lumpa Church=== |

| − | In | + | In 1964, the year of Zambia's independence, Kaunda had to deal with the independent Lumpa Church, led by Alice Lenshina in Chinsali, his home district in the Northern Province. His struggles with the Lumpa Church became a constant problem for Kaunda. The Lumpa Church rejected all earthly authority. It used its own courts and refused to pay taxes or be registered with the state. The church tried to take up a neutral position in the political conflict between UNIP and the ANC, but was accused by UNIP of collaboration with the white minority governments. |

| − | + | Conflicts arose between UNIP youth and Lumpa members, especially in Chinsali District, the headquarters of the church. Kaunda, as prime minister, sent in two battalions of the Northern Rhodesia Regiment, which led to the deaths of about 1,500 villagers and the flight to Katanga of tens of thousands of followers of Lenshina. Kaunda banned the Lumpa Church in August 1964 and proclaimed a state of emergency that was retained until 1991. | |

| − | == | + | ===One-Party State and "African Socialism"=== |

| − | In 1964, | + | In 1964, Kaunda declared a state of emergency to deal with the Lumpa Church crisis, which gave him nearly absolute power and lasted until he left office in 1991. Violence that began on a small scale escalated into a small [[civil war]] in which several thousand people were reportedly killed. |

| − | + | Kaunda increasingly became intolerant of opposition and banned all parties except UNIP, following violence during the 1968 elections. In 1972, he made [[Zambia]] a one-party state. The ANC ceased to exist after the dissolution of parliament in October 1973. | |

| − | + | Kaunda kept his enemies at bay in several different ways. The most common method was to insure that they could not run for President. National activists Harry Mwaanga and Baldwin Nkumbula, both of whom were heavily involved in the struggle for independence from Northern Rhodesia, were eliminated when Kaunda was able to obtain a new UNIP rule that required each presidential candidate to have the signatures of at least 200 delegates from ''each'' province. Another potential presidential candidate, Robert Chiluwe, could also not obtain the required number of supporters. He was eventually declared bankrupt when his bank accounts were frozen. He was also beaten up by the UNIP Youth Wing, the party militants who meted out [[punishment]] to anyone accused of disrespecting party leadership. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Simon Kapwepwe, another leader of the independence movement who opposed Kaunda's sole candidacy for the 1978 UNIP elections, was effectively eliminated from the political process when he was told that he was not eligible to run against Kaunda because only people who had been members in UNIP for at least five years could be nominated to the presidency (he had only joined UNIP three years before). | |

| − | + | With no more opposition remaining, Kaunda fostered the creation of a [[personality cult]]. He developed a national [[ideology]], called "Zambian Humanism." To elaborate his ideology, Kaunda published several books: ''Humanism in Zambia and a Guide to its Implementation, Parts 1, 2 and 3.'' Other publications on Zambian Humanism are: ''Fundamentals of Zambian Humanism,'' by Timothy Kandeke; ''Zambian Humanism, religion and social morality,'' by Cleve Dillion-Malone S.J., and ''Zambian Humanism: some major spiritual and economic challenges,'' by Justin B. Zulu. | |

| − | + | In 1967, Kaunda signed a treaty with [[Peoples' Republic of China|Red China]] and two years later [[nationalization|nationalized]] all foreign industries and corporations. In 1972, the Assembly passed a law making the ruling United National Independence Party (UNIP) the only legal party. All other political parties were brutally suppressed. The prisons were filled with political opponents and critics of the President. Zambia then signed a treaty with the [[Soviet Union]]. Some of the highest ranking Soviet officials—including the Soviet president—visited the country. Soviet, [[North Korea]]n, and [[Cuba]]n military advisers were a common sight. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Between 1967 and 1972, Zambia played host to an assortment of [[Marxism|Marxist]] revolutionary movements. The MPLA, Frelimo, ZANU, ZAPU, SWAPO, the PAC, and the ANC all used Zambia as a launching pad for military or [[terrorism|terrorist attacks]] against such neighboring nations as [[Mozambique]], [[Angola]], Southwest [[Africa]], [[Rhodesia]], and [[South Africa]]. SWAPO and the ANC even ran concentration camps in Zambia for those who opposed them. Those who escaped were hunted down by the Zambian police and handed back to SWAPO or the ANC for [[torture]] or execution. Thousands of members of SWAPO and the ANC were also killed by their own people on Zambian soil. | |

| − | + | ===Educational policies=== | |

| + | At independence, [[Zambia]] had just 109 university graduates and less than 0.5 percent of the population was estimated to have completed primary education. The nation's educational system was one of the most poorly developed in all of Britain's former colonies. Kaunda instituted a policy where all children, irrespective of their parents' ability to pay, were given ''free exercise books, pens and pencils.'' The parents' main responsibility was to buy uniforms, pay a token "school fee," and ensure that the children attended school. Not every child could go to secondary school, however. | ||

| − | + | The University of Zambia was opened in Lusaka in 1966, after Zambians all over the country had been encouraged to donate whatever they could afford toward its construction. Kaunda had himself appointed chancellor and officiated at the first graduation ceremony in 1969. The main campus was situated on the Great East Road, while the medical campus was located at Ridgeway near the University Teaching Hospital. In 1979, another campus was established at the Zambia Institute of Technology in Kitwe. In 1988 the Kitwe campus was upgraded and renamed the Copperbelt University, offering business studies, industrial studies and environmental studies. The University of Zambia offered courses in [[agriculture]], [[education]], [[engineering]], humanities and social sciences, law, [[medicine]], [[mining]], natural sciences, and [[veterinary medicine]]. The basic program is four years long, although engineering and medical courses are five and seven years long, respectively. | |

| − | + | Other tertiary-level institutions established during Kaunda's era were vocationally focused and fell under the aegis of the Department of Technical Education and Vocational Training. They include the Evelyn Hone College of Applied Arts and Commerce and the Natural Resources Development College (both in Lusaka), the Northern Technical College at Ndola, the Livingstone Trades Training Institute in Livingstone, and teacher-training colleges. | |

| − | === | + | ===Economic policies=== |

| − | + | At independence, [[Zambia]] was a country with an economy largely under the control of white Africans and foreigners. For example, the British South Africa Company (BSAC) retained commercial assets and [[mineral rights]] that it claimed it acquired from a concession signed with the Litunga of Bulozi in 1890 (the Lochner Concession). By threatening to expropriate it, on the eve of independence, Kaunda managed to get the BSAC to assign its mineral rights to the incoming Zambian government. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1975, a slump in copper prices and a severe decrease in export earnings resulted in Zambia having a massive balance of payments crisis and debt to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Zambia under Kaunda's leadership instituted a program of national development plans, under the direction of the National Commission for Development Planning: first, the Transitional Development Plan, which was followed by the First National Development Plan (1966–1971). These two plans provided for major investment in infrastructure and manufacturing. They were generally successful. This was not true for subsequent plans. | |

| − | + | A major switch in the structure of Zambia's economy came with the Mulungushi Reforms of April 1968: the government declared its intention to acquire an equity holding (usually 51 percent or more) in a number of key foreign-owned firms, to be controlled by the Industrial Development Corporation (INDECO). By January 1970, Zambia had acquired majority holding in the Zambian operations of the two major foreign mining corporations, the Anglo American Corporation and the Rhodesia Selection Trust (RST); the two became the Nchanga Consolidated Copper Mines (NCCM) and Roan Consolidated Mines (RCM), respectively. | |

| + | Kaunda announced the creation of a new company owned or controlled wholly or partly by the government—the Mining Development Corporation (MINDECO). The Finance and Development Corporation (FINDECO) allowed the Zambian government to gain control of insurance companies and building societies. | ||

| − | + | Foreign-owned banks, such as Barclays, Standard Chartered and Grindlays, however, successfully resisted takeover. However, in 1971, INDECO, MINDECO, and FINDECO were brought together under a government owned entity or parastatal, the Zambia Industrial and Mining Corporation (ZIMCO), to create one of the largest companies in sub-Saharan Africa, with Kaunda as chairman. The management contracts under which day-to-day operations of the mines had been carried out by Anglo American and RST were ended in 1973. In 1982, NCCM and RCM were merged into the giant Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Ltd (ZCCM). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Unfortunately, these policies, as well as events that were beyond Kaunda's control would wreck the country's plans for national development. In 1973, the massive increase in the price of oil was followed by a slump in copper prices in 1975 and a diminution of export earnings. In 1973 the price of copper accounted for 95 percent of all export earnings; this halved in value on the world market in 1975. By 1976, Zambia had a balance-of-payments crisis, and rapidly became massively indebted to the International Monetary Fund. The Third National Development Plan (1978–1983) had to be abandoned as crisis management replaced long-term planning. | |

| − | + | By the mid-1980s, Zambia was one of the most indebted nations in the world, relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). The IMF recommended that the Zambian government should introduce programs aimed at stabilizing the economy and restructuring it to reduce dependence on [[copper]]. The proposed measures included: the ending of price controls; devaluation of the ''kwacha'' (Zambia's currency); cut-backs in government expenditure; cancellation of subsidies on food and fertilizer; and increased prices for farm produce. Kaunda's removal of food subsidies caused massive increases in the prices of basic foodstuffs; the country's urban population rioted in protest. In desperation, Kaunda broke with the IMF in May 1987 and introduced a New Economic Recovery Program in 1988. However, this failed to achieve success, and he eventually moved toward a new understanding with the IMF in 1989. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1990, with the collapse of the [[Soviet Union]] and Eastern Europe, Kaunda was forced to make a major policy shift: he announced the intention to partially privatize various state-owned corporations. However, these changes came too late to prevent his fall from power, which was largely the result of the economic troubles. | |

| − | + | ===Foreign policy=== | |

| + | During his early presidency he was an outspoken supporter of the anti-[[apartheid]] movement and opposed [[Ian Smith|Ian Smith]]'s white minority rule in [[Rhodesia]]. As mentioned above, Kaunda allowed several African liberation fronts such as ZAPU and ZANU of Rhodesia and African National Congress to set up headquarters in [[Zambia]]. The struggle in both Rhodesia and South Africa and its offshoot wars in Namibia, Angola and Mozambique placed a huge economic burden on Zambia as these were the country's main trading partners. When [[Nelson Mandela]] was released from prison in 1990 the first country he visited was Zambia. | ||

| − | + | During the [[Cold War]] years Kaunda was a strong supporter of the so-called "[[Non-Aligned Movement]]." He hosted a NAM summit in Lusaka in 1970 and served as the movement’s chairman from 1970 to 1973. He maintained warm relations with the [[People's Republic of China]] who had provided assistance on many projects in Zambia. He also had a close friendship with [[Yugoslavia|Yugoslavia]]'s long-time leader [[Tito]]. He had frequent differences with United States President [[Ronald Reagan|Reagan]]<ref>[https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/remarks-president-reagan-and-president-kenneth-kaunda-zambia-following-their Remarks by President Reagan and President Kaunda, March 30, 1983], ''Ronald Reagan Presidential Library''. Retrieved August 24, 2023.</ref> and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_pictures/3945291.stm 40 Years of Zambia in pictures], ''BBC News''. Retrieved August 24, 2023.</ref> mainly over what he saw as the West's blind eye to apartheid, in addition to his economic and social policies. In the late 1980s, prior to the first [[Gulf War]], Kaunda developed a friendship with [[Saddam Hussein]] with whom he struck various agreements to supply oil to Zambia. | |

| − | === | + | ==Fall from Power== |

| − | + | Eventually, economic troubles and increasing international pressure for more democracy forced Kaunda to change the rules that had kept him in power for so many years. People who had been afraid to criticize him were now emboldened to challenge his competence. His close friend [[Julius Nyerere]] had stepped down from the presidency in [[Tanzania]] in 1985 and was quietly encouraging Kaunda to follow suit. Pressure for a return to multi-party politics increased, and Kaunda finally yielded and called for new elections in 1991, in which the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) won. Kaunda left office with the inauguration of MMD leader [[Frederick Chiluba]] as president on November 2, 1991. | |

| − | + | ==Post-presidency== | |

| + | After his successful bid for the presidency, Chiluba attempted to deport Kaunda on the grounds that he was not Zambian, but from neighboring [[Malawi]]. The MMD-dominated government under the leadership of Chiluba had the constitution amended, barring citizens with foreign parentage from standing for the presidency, and to prevent Kaunda from contesting the next elections in 1996. Kaunda retired from politics after he was accused of involvement in a failed 1997 [[coup d'etat|coup]] attempt. | ||

| − | + | After retiring, Kaunda was involved in various charitable organizations. From 2002 to 2004, he was an African President in Residence at Boston University. | |

| − | + | ==Death== | |

| + | Kenneth Kaunda died on June 17, 2021 at Mina Soko Medical Centre in Lusaka. The government announced a 21-day mourning period. During the mourning period Kaunda's body was taken around all 10 provincial towns and in each provincial capital, and a short church ceremony was conducted by the Military and the [[United Church in Zambia|United Church of Zambia]] which Kaunda belonged. The state funeral took place on July 2. Due to the [[COVID-19 pandemic in Zambia|COVID-19]] restrictions attendance was strictly by invitation. The funeral service was broadcast on [[Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation|national TV]] networks in [[Zambia]], [[South Africa]] and around the region. | ||

| − | + | Several African countries had declared an official period of national mourning. [[Zimbabwe]] declared fourteen days of mourning; [[South Africa]] declared ten days of mourning; [[Botswana]], [[Malawi]], [[Namibia]], and [[Tanzania]] all declared seven days of mourning; [[Mozambique]] declared six days of mourning; and [[South Sudan]] declared three days of mourning. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Kaunda's funeral took place at Lusaka Show Grounds on July 2, 2021, after his body had its last provincial visit. Ordinary Zambian citizens came out to show their last respects as they waved their white handkerchiefs in mourning, an item Kaunda carried with him when he was incarcerated during the struggle for liberation. During the state funeral, a 21-gun salute was given to the former president. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | Present-day [[Zambia]] is one of [[Sub-Saharan Africa]]'s most highly urbanized countries. More than a quarter of Zambia's population lives in two urban areas near the center: in the capital, Lusaka, and in the industrial towns of the Copperbelt (Ndola, Kitwe, Chingola, Luanshya and Mufulira). The rest of Zambia is very sparsely populated, particularly the west and the northeast; the majority of people make their living as subsistence farmers. | ||

| − | + | Kenneth Kaunda was the first President of Zambia and one of the major leaders of Zambia's independence movement. But many of the methods he used and his alliances with the [[Soviet Union]] and [[Cuba]] branded him as a misguided [[socialism|socialist]] revolutionary. For some he is remembered as an autocratic ruler with his "one party" state. But for many Africans, especially because of his fierce lifelong opposition to [[apartheid]], Kaunda is regarded as one of the founding founders of modern Africa. | |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Ipenburg, A. N. ''All Good Men. The Development of Lubwa Mission, Chinsali, Zambia, 1905-1967.'' Peter Lang Pub Inc., 1992. ISBN 9783631453384 | |

| − | * | + | * Macpherson, Fergus. ''Kenneth Kaunda: The Times and the Man.'' Oxford University Press Southern Africa, 1975. ISBN 9780195723373 |

| − | * | + | * Hall, Richard. ''The High Price of Principles: Kaunda and the White South.'' Penguin, 1973. ISBN 9780140410341 |

| − | * | + | * Mulford, David C., ''Zambia: The Politics of Independence, 1957–1964.'' Oxford U.P, 1967. {{ASIN|B0006BSSK2}} |

| − | * | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/25/newsid_2658000/2658325.stm 1964: President Kaunda takes power in Zambia] | + | All links retrieved August 24, 2023. |

| − | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/ | + | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/25/newsid_2658000/2658325.stm 1964: President Kaunda takes power in Zambia] ''BBC''. |

| + | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/6728015.stm Kaunda on Mugabe] ''BBC''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{{start box}} | {{start box}} | ||

| Line 137: | Line 143: | ||

{{end box}} | {{end box}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|149048707}} | {{Credit|149048707}} | ||

| + | [[Category:History]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:28, 24 August 2023

| Kenneth Kaunda | |

| |

1st President of Zambia

| |

| In office October 24, 1964 – November 2, 1991 | |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Chiluba |

|---|---|

3rd Secretary General of Non-Aligned Movement

| |

| In office September 10, 1970 – September 9, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Gamal Abdel Nasser |

| Succeeded by | Houari Boumédienne |

| Born | April 28 1924 (age 99) Chinsali, Northern Rhodesia |

| Died | June 17 2021 (aged 97) Lusaka, Zambia |

| Political party | United National Independence Party |

| Spouse | Betty Kaunda |

| Profession | Teacher |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

Kenneth David Kaunda, (April 28, 1924 - June 17, 2021) served as the first president of Zambia, from 1964 to 1991. He played a major role in Zambia's independence movement which sought to free itself from Rhodesia and white minority rule. For his efforts, Kaunda suffered imprisonment and several confrontations with rival groups.

From the time he became President until his fall from power in 1991, Kaunda ruled under emergency powers, eventually banning all parties except his own United National Independence Party. While president, he dealt in autocratic fashion with severe economic problems and challenges to his power, aligning his country against the West and instituting, with little success, socialist economic policies. Eventually because of mounting international pressure for more democracy in Africa, and continuing economic problems, Kaunda was forced out of office in 1991.

Overall, however, Kaunda is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern Africa.

Early life

Kaunda was the youngest of eight children. He was born at Lubwa Mission in Chinsali, Northern Province of Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia. His father was the Reverend David Kaunda, an ordained Church of Scotland missionary and teacher, who was born in Malawi and had moved to Chinsali to work at Lubwa Mission. He attended Munali Training Centre in Lusaka (August 1941–1943).

Kaunda was first a teacher at the Upper Primary School and boarding master at Lubwa and then headmaster at Lubwa from 1943 to 1945. He left Lubwa for Lusaka to become an instructor in the army, but was dismissed. He was for a time working at the Salisbury and Bindura Mine. In early 1948, he became a teacher in Mufulira for the United Missions to the Copperbelt (UMCB). He was then assistant at an African welfare center and Boarding Master of a mine school in Mufulira. In this period, he led a Pathfinder Scout group and was choirmaster at a Church of Central Africa Congregation. He was also for a time vice-secretary of the Nchanga Branch of Congress.

Kaunda married Betty Banda in 1946, with whom he had eight children. She died on September 17, 2013, aged 87, while visiting one of their daughters in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Independence struggle

In 1949, Kaunda became an interpreter and adviser on African affairs to Sir Stewart Gore-Browne, a white settler and member of the Northern Rhodesian Legislative Council. Kaunda acquired knowledge of the colonial government and learned valuable political skills, both of which served him well when later that year he joined the African National Congress (ANC), the first major anti-colonial organization in Northern Rhodesia. In the early 1950s Kaunda became the ANC's secretary-general. He served as an organizing officer, a role that brought him into close contact with the movement's rank and file. Thus, when the leadership of the ANC clashed over strategy in 1958–1959, Kaunda carried a major part of the ANC operating structure into a new organization, the Zambia African National Congress.

In April 1949, Kaunda returned to Lubwa to become a part-time teacher, but resigned in 1951. In that year, he became an organizing secretary of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress for Northern Province, which included at that time Luapula Province. In November 1953 he moved to Lusaka to take up the post of Secretary General of the ANC, under the presidency of Harry Nkumbula. The combined efforts of Kaunda and Nkumbula at that time were unsuccessful in mobilizing African people against the white-dominated Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. In 1955, Kaunda and Nkumbula were imprisoned for two months at hard labor for distributing subversive literature. Such imprisonment and other forms of harassment were customary for African nationalist leaders. However, the experience of imprisonment had a radicalizing impact on Kaunda.

Kaunda and Nkumbula drifted apart as Nkumbula became increasingly influenced by white liberals and was seen as being willing to compromise on the issue of majority rule. Nkumbula's allegedly autocratic leadership of the ANC eventually resulted in a complete split. Kaunda broke from the ANC and formed the Zambian African National Congress (ZANC) in October 1958.

ZANC was banned in March 1959. In June 1959, Kaunda was sentenced to nine months' imprisonment, which he spent first in Lusaka, then in Salisbury (Harare). While Kaunda was in prison, Mainza Chona and other nationalists broke away from the ANC. In October 1959, Chona became the first president of the United National Independence Party (UNIP), the successor to ZANC. However, Chona did not see himself as the party's main founder. When Kaunda was released from prison in January 1960 he was elected President of UNIP. In July 1961, Kaunda organized a violent civil disobedience campaign in Northern Province which consisted of burning schools and blocking roads.

Kaunda ran as an UNIP candidate during the 1962 elections. This resulted in a UNIP–ANC Coalition Government, with Kaunda as Minister of Local Government and Social Welfare. In January 1964, UNIP won the general election under the new constitution, beating the ANC under Nkumbula. Kaunda was appointed prime minister. On October 24, 1964 he became the first president of independent Zambia. Simon Kapwepwe was appointed as the first Vice President.

Presidency

Kaunda ruled under a state of emergency from the time he became president until his fall from power in 1991. Becoming increasingly intolerant of opposition, Kaunda eventually banned all parties except his own UNIP, following violence during the 1968 elections.

Lumpa Church

In 1964, the year of Zambia's independence, Kaunda had to deal with the independent Lumpa Church, led by Alice Lenshina in Chinsali, his home district in the Northern Province. His struggles with the Lumpa Church became a constant problem for Kaunda. The Lumpa Church rejected all earthly authority. It used its own courts and refused to pay taxes or be registered with the state. The church tried to take up a neutral position in the political conflict between UNIP and the ANC, but was accused by UNIP of collaboration with the white minority governments.

Conflicts arose between UNIP youth and Lumpa members, especially in Chinsali District, the headquarters of the church. Kaunda, as prime minister, sent in two battalions of the Northern Rhodesia Regiment, which led to the deaths of about 1,500 villagers and the flight to Katanga of tens of thousands of followers of Lenshina. Kaunda banned the Lumpa Church in August 1964 and proclaimed a state of emergency that was retained until 1991.

One-Party State and "African Socialism"

In 1964, Kaunda declared a state of emergency to deal with the Lumpa Church crisis, which gave him nearly absolute power and lasted until he left office in 1991. Violence that began on a small scale escalated into a small civil war in which several thousand people were reportedly killed.

Kaunda increasingly became intolerant of opposition and banned all parties except UNIP, following violence during the 1968 elections. In 1972, he made Zambia a one-party state. The ANC ceased to exist after the dissolution of parliament in October 1973.

Kaunda kept his enemies at bay in several different ways. The most common method was to insure that they could not run for President. National activists Harry Mwaanga and Baldwin Nkumbula, both of whom were heavily involved in the struggle for independence from Northern Rhodesia, were eliminated when Kaunda was able to obtain a new UNIP rule that required each presidential candidate to have the signatures of at least 200 delegates from each province. Another potential presidential candidate, Robert Chiluwe, could also not obtain the required number of supporters. He was eventually declared bankrupt when his bank accounts were frozen. He was also beaten up by the UNIP Youth Wing, the party militants who meted out punishment to anyone accused of disrespecting party leadership.

Simon Kapwepwe, another leader of the independence movement who opposed Kaunda's sole candidacy for the 1978 UNIP elections, was effectively eliminated from the political process when he was told that he was not eligible to run against Kaunda because only people who had been members in UNIP for at least five years could be nominated to the presidency (he had only joined UNIP three years before).

With no more opposition remaining, Kaunda fostered the creation of a personality cult. He developed a national ideology, called "Zambian Humanism." To elaborate his ideology, Kaunda published several books: Humanism in Zambia and a Guide to its Implementation, Parts 1, 2 and 3. Other publications on Zambian Humanism are: Fundamentals of Zambian Humanism, by Timothy Kandeke; Zambian Humanism, religion and social morality, by Cleve Dillion-Malone S.J., and Zambian Humanism: some major spiritual and economic challenges, by Justin B. Zulu.

In 1967, Kaunda signed a treaty with Red China and two years later nationalized all foreign industries and corporations. In 1972, the Assembly passed a law making the ruling United National Independence Party (UNIP) the only legal party. All other political parties were brutally suppressed. The prisons were filled with political opponents and critics of the President. Zambia then signed a treaty with the Soviet Union. Some of the highest ranking Soviet officials—including the Soviet president—visited the country. Soviet, North Korean, and Cuban military advisers were a common sight.

Between 1967 and 1972, Zambia played host to an assortment of Marxist revolutionary movements. The MPLA, Frelimo, ZANU, ZAPU, SWAPO, the PAC, and the ANC all used Zambia as a launching pad for military or terrorist attacks against such neighboring nations as Mozambique, Angola, Southwest Africa, Rhodesia, and South Africa. SWAPO and the ANC even ran concentration camps in Zambia for those who opposed them. Those who escaped were hunted down by the Zambian police and handed back to SWAPO or the ANC for torture or execution. Thousands of members of SWAPO and the ANC were also killed by their own people on Zambian soil.

Educational policies

At independence, Zambia had just 109 university graduates and less than 0.5 percent of the population was estimated to have completed primary education. The nation's educational system was one of the most poorly developed in all of Britain's former colonies. Kaunda instituted a policy where all children, irrespective of their parents' ability to pay, were given free exercise books, pens and pencils. The parents' main responsibility was to buy uniforms, pay a token "school fee," and ensure that the children attended school. Not every child could go to secondary school, however.

The University of Zambia was opened in Lusaka in 1966, after Zambians all over the country had been encouraged to donate whatever they could afford toward its construction. Kaunda had himself appointed chancellor and officiated at the first graduation ceremony in 1969. The main campus was situated on the Great East Road, while the medical campus was located at Ridgeway near the University Teaching Hospital. In 1979, another campus was established at the Zambia Institute of Technology in Kitwe. In 1988 the Kitwe campus was upgraded and renamed the Copperbelt University, offering business studies, industrial studies and environmental studies. The University of Zambia offered courses in agriculture, education, engineering, humanities and social sciences, law, medicine, mining, natural sciences, and veterinary medicine. The basic program is four years long, although engineering and medical courses are five and seven years long, respectively.

Other tertiary-level institutions established during Kaunda's era were vocationally focused and fell under the aegis of the Department of Technical Education and Vocational Training. They include the Evelyn Hone College of Applied Arts and Commerce and the Natural Resources Development College (both in Lusaka), the Northern Technical College at Ndola, the Livingstone Trades Training Institute in Livingstone, and teacher-training colleges.

Economic policies

At independence, Zambia was a country with an economy largely under the control of white Africans and foreigners. For example, the British South Africa Company (BSAC) retained commercial assets and mineral rights that it claimed it acquired from a concession signed with the Litunga of Bulozi in 1890 (the Lochner Concession). By threatening to expropriate it, on the eve of independence, Kaunda managed to get the BSAC to assign its mineral rights to the incoming Zambian government.

In 1975, a slump in copper prices and a severe decrease in export earnings resulted in Zambia having a massive balance of payments crisis and debt to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Zambia under Kaunda's leadership instituted a program of national development plans, under the direction of the National Commission for Development Planning: first, the Transitional Development Plan, which was followed by the First National Development Plan (1966–1971). These two plans provided for major investment in infrastructure and manufacturing. They were generally successful. This was not true for subsequent plans.

A major switch in the structure of Zambia's economy came with the Mulungushi Reforms of April 1968: the government declared its intention to acquire an equity holding (usually 51 percent or more) in a number of key foreign-owned firms, to be controlled by the Industrial Development Corporation (INDECO). By January 1970, Zambia had acquired majority holding in the Zambian operations of the two major foreign mining corporations, the Anglo American Corporation and the Rhodesia Selection Trust (RST); the two became the Nchanga Consolidated Copper Mines (NCCM) and Roan Consolidated Mines (RCM), respectively.

Kaunda announced the creation of a new company owned or controlled wholly or partly by the government—the Mining Development Corporation (MINDECO). The Finance and Development Corporation (FINDECO) allowed the Zambian government to gain control of insurance companies and building societies.

Foreign-owned banks, such as Barclays, Standard Chartered and Grindlays, however, successfully resisted takeover. However, in 1971, INDECO, MINDECO, and FINDECO were brought together under a government owned entity or parastatal, the Zambia Industrial and Mining Corporation (ZIMCO), to create one of the largest companies in sub-Saharan Africa, with Kaunda as chairman. The management contracts under which day-to-day operations of the mines had been carried out by Anglo American and RST were ended in 1973. In 1982, NCCM and RCM were merged into the giant Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Ltd (ZCCM).

Unfortunately, these policies, as well as events that were beyond Kaunda's control would wreck the country's plans for national development. In 1973, the massive increase in the price of oil was followed by a slump in copper prices in 1975 and a diminution of export earnings. In 1973 the price of copper accounted for 95 percent of all export earnings; this halved in value on the world market in 1975. By 1976, Zambia had a balance-of-payments crisis, and rapidly became massively indebted to the International Monetary Fund. The Third National Development Plan (1978–1983) had to be abandoned as crisis management replaced long-term planning.

By the mid-1980s, Zambia was one of the most indebted nations in the world, relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). The IMF recommended that the Zambian government should introduce programs aimed at stabilizing the economy and restructuring it to reduce dependence on copper. The proposed measures included: the ending of price controls; devaluation of the kwacha (Zambia's currency); cut-backs in government expenditure; cancellation of subsidies on food and fertilizer; and increased prices for farm produce. Kaunda's removal of food subsidies caused massive increases in the prices of basic foodstuffs; the country's urban population rioted in protest. In desperation, Kaunda broke with the IMF in May 1987 and introduced a New Economic Recovery Program in 1988. However, this failed to achieve success, and he eventually moved toward a new understanding with the IMF in 1989.

In 1990, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, Kaunda was forced to make a major policy shift: he announced the intention to partially privatize various state-owned corporations. However, these changes came too late to prevent his fall from power, which was largely the result of the economic troubles.

Foreign policy

During his early presidency he was an outspoken supporter of the anti-apartheid movement and opposed Ian Smith's white minority rule in Rhodesia. As mentioned above, Kaunda allowed several African liberation fronts such as ZAPU and ZANU of Rhodesia and African National Congress to set up headquarters in Zambia. The struggle in both Rhodesia and South Africa and its offshoot wars in Namibia, Angola and Mozambique placed a huge economic burden on Zambia as these were the country's main trading partners. When Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990 the first country he visited was Zambia.

During the Cold War years Kaunda was a strong supporter of the so-called "Non-Aligned Movement." He hosted a NAM summit in Lusaka in 1970 and served as the movement’s chairman from 1970 to 1973. He maintained warm relations with the People's Republic of China who had provided assistance on many projects in Zambia. He also had a close friendship with Yugoslavia's long-time leader Tito. He had frequent differences with United States President Reagan[1] and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher[2] mainly over what he saw as the West's blind eye to apartheid, in addition to his economic and social policies. In the late 1980s, prior to the first Gulf War, Kaunda developed a friendship with Saddam Hussein with whom he struck various agreements to supply oil to Zambia.

Fall from Power

Eventually, economic troubles and increasing international pressure for more democracy forced Kaunda to change the rules that had kept him in power for so many years. People who had been afraid to criticize him were now emboldened to challenge his competence. His close friend Julius Nyerere had stepped down from the presidency in Tanzania in 1985 and was quietly encouraging Kaunda to follow suit. Pressure for a return to multi-party politics increased, and Kaunda finally yielded and called for new elections in 1991, in which the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) won. Kaunda left office with the inauguration of MMD leader Frederick Chiluba as president on November 2, 1991.

Post-presidency

After his successful bid for the presidency, Chiluba attempted to deport Kaunda on the grounds that he was not Zambian, but from neighboring Malawi. The MMD-dominated government under the leadership of Chiluba had the constitution amended, barring citizens with foreign parentage from standing for the presidency, and to prevent Kaunda from contesting the next elections in 1996. Kaunda retired from politics after he was accused of involvement in a failed 1997 coup attempt.

After retiring, Kaunda was involved in various charitable organizations. From 2002 to 2004, he was an African President in Residence at Boston University.

Death

Kenneth Kaunda died on June 17, 2021 at Mina Soko Medical Centre in Lusaka. The government announced a 21-day mourning period. During the mourning period Kaunda's body was taken around all 10 provincial towns and in each provincial capital, and a short church ceremony was conducted by the Military and the United Church of Zambia which Kaunda belonged. The state funeral took place on July 2. Due to the COVID-19 restrictions attendance was strictly by invitation. The funeral service was broadcast on national TV networks in Zambia, South Africa and around the region.

Several African countries had declared an official period of national mourning. Zimbabwe declared fourteen days of mourning; South Africa declared ten days of mourning; Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, and Tanzania all declared seven days of mourning; Mozambique declared six days of mourning; and South Sudan declared three days of mourning.

Kaunda's funeral took place at Lusaka Show Grounds on July 2, 2021, after his body had its last provincial visit. Ordinary Zambian citizens came out to show their last respects as they waved their white handkerchiefs in mourning, an item Kaunda carried with him when he was incarcerated during the struggle for liberation. During the state funeral, a 21-gun salute was given to the former president.

Legacy

Present-day Zambia is one of Sub-Saharan Africa's most highly urbanized countries. More than a quarter of Zambia's population lives in two urban areas near the center: in the capital, Lusaka, and in the industrial towns of the Copperbelt (Ndola, Kitwe, Chingola, Luanshya and Mufulira). The rest of Zambia is very sparsely populated, particularly the west and the northeast; the majority of people make their living as subsistence farmers.

Kenneth Kaunda was the first President of Zambia and one of the major leaders of Zambia's independence movement. But many of the methods he used and his alliances with the Soviet Union and Cuba branded him as a misguided socialist revolutionary. For some he is remembered as an autocratic ruler with his "one party" state. But for many Africans, especially because of his fierce lifelong opposition to apartheid, Kaunda is regarded as one of the founding founders of modern Africa.

Notes

- ↑ Remarks by President Reagan and President Kaunda, March 30, 1983, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ↑ 40 Years of Zambia in pictures, BBC News. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ipenburg, A. N. All Good Men. The Development of Lubwa Mission, Chinsali, Zambia, 1905-1967. Peter Lang Pub Inc., 1992. ISBN 9783631453384

- Macpherson, Fergus. Kenneth Kaunda: The Times and the Man. Oxford University Press Southern Africa, 1975. ISBN 9780195723373

- Hall, Richard. The High Price of Principles: Kaunda and the White South. Penguin, 1973. ISBN 9780140410341

- Mulford, David C., Zambia: The Politics of Independence, 1957–1964. Oxford U.P, 1967. ASIN B0006BSSK2

External links

All links retrieved August 24, 2023.

| Preceded by: (–) |

Prime Minister of Northern Rhodesia 1964 |

Succeeded by: (–) |

| Preceded by: (none) |

President of Zambia 1964–1991 |

Succeeded by: Frederick Chiluba |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.