Jackdaw

| Jackdaw | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Corvus monedula (Linnaeus, 1758) | ||||||||||||||

Jackdaw range

|

Jackdaw is the common name for a Eurasian bird, Corvus monedula, one of the smallest species in the genus of crows and ravens, characterized by black plumage, a gray nape, and distinctive gray-white iris. It is found across Europe, western Asia and North Africa. It is sometimes known as the Eurasian jackdaw, European jackdaw, Western jackdaw, or formerly simply the daw.

The term jackdaw also is used for another member of the Corvus genus, the Daurian jackdaw (Corvus dauricus). These are quite similar in appearance and habits, but the Daurian jackdaw has a black iris, and many of the Daurian jackdaws have large areas of creamy white on the lower parts, extending up around the neck in a thick collar. This article, however, will be limited to discussion of Corvus monedula.

Overview and description

is one of the smallest species (34–39 cm in length) in the genus of crows and ravens. It is a black-plumaged bird with grey nape and distinctive white irises. Like all corvids, it is omnivorous. It is found across Europe, western Asia and North Africa. Four subspecies are currently recognised.

- It is the same size or perhaps slightly smaller (32 cm in length) than the latter species, with the same proportions and identical habits. The principal difference is its plumage; many but not all adults of this species have large areas of creamy white on the lower parts extending up around the neck as a thick collar. The head, throat, wings and tail are glossy black and the ear coverts are grizzled grey. Darker adults and young birds resemble Eurasian Jackdaws, though Daurian Jackdaws have a black iris, unlike the distinctive grey-white iris of the Eurasian Jackdaw.

- Crow is the common name for various large passerine birds in the genus Corvus of the family Corvidae, typically distinguished from ravens by smaller size and without the raven's shaggy throat feathers. The term crow also can be considered a more general term for all members of the Corvus genus, including ravens, rooks (one extant species), and jackdaws (two species).

- Tropical Asian species

- Daurian Jackdaw C. dauricus

- Like other members of the Corvidae family (jays, magpies, treepies and nutcrackers), members of the Corvus genus are characterized by strong feet and bills, feathered, rounded nostrils, strong tails and wings, rictal bristles, and a single molt each year (most passerines molt twice). The genus Corvus, including the crows, ravens, rooks (C. frugilegus), and jackdaws (C. dauricus and C. monedula), makes up over a third of the entire family.

Taxonomy

The Jackdaw was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th century work, Systema Naturae, and it still bears its original name of Corvus monedula.[2] The species name monedula is the Latin for jackdaw.[3]

The common name jackdaw first appears in the 16th century, and is a compound of the forename Jack used in animal names to signify a small form (e.g. jack-snipe) and the native English word daw. Formerly jackdaws were simply called daws (the only form in Shakespeare). Claims that the metallic chyak call is the origin of the jack part of the common name[4] are not supported by the Oxford English Dictionary.[5]

Daw is first attested in the 15th century, which the Oxford English Dictionary conjectures to be derived from an unattested Old English dawe, citing cognates in Old High German tâha, Middle High German tâhe and modern German dialect dähi, däche, dacha.

The original Old English name was ceo (pronounced with initial ch). Though now reserved for corvids of the genus Pyrrhocorax the word chough originally referred to the jackdaw.

English dialect names are numerous. Scottish and north England dialect has had ka or kae since the 14th century. The midlands form of this was co or coo. Caddow is potentially a compound of ka and dow, a variant of daw. Other dialect or obsolete names include caddesse, cawdaw, caddy, chauk, college-bird (from dialect college = cathedral), jackerdaw, jacko, ka-wattie, chimney-sweep bird, from their nesting propensities, and sea-crow, from their frequenting coasts. It was also frequently known quasi-nominally as Jack.[6][7][8][9]

An archaic collective noun for a group of jackdaws is a "clattering".[10] Another term used is "train,"[11] however, in practice, most people use the more generic term "flock".

Subspecies

There are four recognised subspecies[12][9]

- nominate C. m. monedula (Linnaeus, 1758) breeding in south-east Norway, southern Sweden and northern and eastern Denmark, with occasional wintering birds in England and France; has pale nape and side of the neck, dark throat, light grey partial collar of variable extent;

- C. m. spermologus (Vieillot, 1817) of west and central Europe, wintering to the Canary Islands and Corsica; darker in colour and lacks grey collar

- C. m. soemmerringii (Fischer, 1811) of north-east Europe, and north and central Asia, from former Soviet Union to Lake Baikal and north-west Mongolia and south to Turkey, Israel and the eastern Himalayas, and winters in Iran and NW India (Kashmir); distinguished by paler nape and side of the neck creating a contrasting black crown, and lighter grey partial collar;

- C. m. cirtensis (Rothschild and Hartert, 1912) of N Africa (Morocco and Algeria)

C. m. Monedula integrates into C. m. soemmerringii with the transition zone running from Finland south across the Baltic, east Poland to Romania and Croatia.[13]

Description

Measuring 34–39 cm (14-15 in), the jackdaw is the smallest species in the genus Corvus. Most of the plumage is black or greyish black except for the cheeks, nape and neck, which are light grey to greyish silver. The iris of adults is greyish white or silvery white, the only member of the genus outside of the Australasian region to have this feature. The iris of juvenile jackdaws is light blue.

In flight, jackdaws are separable from other corvids by their smaller size, faster and deepers wingbeats and proportionately narrower and less fingered wings. They also have a shorter, thicker neck, a much shorter bill and frequently fly in tighter flocks. Underwing is uniformly grey, unlike choughs.

On the ground, jackdaws strut about briskly and have an upright posture.

Sexes and ages are alike.[14][9]

Voice

Jackdaws are voluble birds. The call, frequently given in flight, is a metallic and somewhat squeaky, "chyak-chyak" or "kak-kak". Perched birds often chatter together, and before settling for the night large roosting flocks make a cackling noise. Jackdaws also have a hoarse, drawn-out alarm-call.[9]

Distribution and habitat

Jackdaws are resident over a large area stretching from North West Africa through virtually all of Europe, including the British Isles and southern Scandinavia, westwards through central Asia to the eastern Himalayas and Lake Baikal. They are resident throughout Turkey, the Caucasus, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and north-west India.

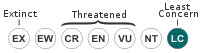

The species has a large range, with an estimated global extent of between 1,000,000 and 10,000,000 km². It has a large global population, with an estimated 10 to 29 million individuals in Europe.[15].

Jackdaws are mostly resident, but the northern and eastern populations are more migratory.[16] Their range expands northwards into Russia to Siberia during summer, and retracts in winter.[9] They are winter vagrants to Lebanon, first recorded there in 1962.[17] In Syria they are winter vagrants and rare residents with some confirmed breeding.[18] The soemmerringii race occurs in south-central Siberia and extreme northwest China and is accidental to Hokkaido, Japan.[19]

A small number of Jackdaws reached the northwest of North America in the 1980s, presumedly ship-assisted, and have been found from Atlantic Canada to Pennsylvania.[20] They have also occurred as vagrants in Canada, the Faroe Islands, Gibraltar, Iceland, Mauritania and Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Jackdaws are regionally extinct in Malta and Tunisia.[21]

They inhabit wooded steppes, woodland, cultivated land, pasture, coastal cliffs and villages and towns.

Behavior

Jackdaws are highly gregarious and are generally seen in small to large flocks, though males and females pair-bond for life and pairs stay together within flocks. Flock sizes increase in autmun and large flocks group together at dusk for communal roosting.[9] They become sexually mature in the first breeding season, and there is little evidence for divorce or extra pair coupling in jackdaws, even after multiple instances of reproductive failure.[22]

Jackdaws frequently congregate with Hooded Crow Corvus cornix,[23] and during migration often accompany Rooks C. frugilegus.

Like magpies, jackdaws are known to steal shiny objects such as jewelry to hoard in nests. John Gay in his Beggar's Opera notes that "A covetous fellow, like a jackdaw, steals what he was never made to enjoy, for the sake of hiding it"[24] and in Tobias Smollett's The Expedition of Humphry Clinker a scathing character assassination by Mr. Bramble runs "He is ungracious as a hog, greedy as a vulture, and thievish as a jackdaw."[25]

Feeding

The jackdaw mostly takes food from the ground but does take some food in trees.

In terms of animal food, jackdaws tend to feed upon small invertebrates found above ground between 2 and 18 mm in length, including imagines, larvae and pupae of Curculionidae, Coleoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera. Snails, spiders and some other insects also make up part of their animal diet. Unlike rooks and carrion crows, jackdaws do not generally feed on carrion, though they will eat stranded fish on the shore. The vegetal diet of jackdaws consists of farm grains (barley, wheat and oats), seeds of weeds, elderberries, acorns and various cultivated fruits.[26] Jackdaws also take scraps of human food in towns, and will more readily take food from bird tables than other Corvus species.

Jackdaws employ various feeding methods, such as jumping, pecking, clod-turning and scattering, probing the soil, and rarely digging. Flies around cow pats are caught by jumping from the ground or at times by dropping vertically from a few metres above onto the cow pat. Earthworms are not usually extracted from the ground by jackdaws but are eaten from freshly plough soil.[26]

Jackdaws practice active food sharing, where the initiative for the transfer lies with the donor, with a number of individuals, regardless of sex and kinship. They also share more of a preferred food than a less preferred food.[27]

Infant jackdaws are altricial and thus are completely dependent on being fed by their parents until they fledge.[22]

Breeding

Jackdaws usually nest in colonies with monogamous pairs collaborating to locate a nest site which they then defend from other pairs and predators most of the year.[22]

Jackdaws nest in cavities of trees, cliffs or ruined, and sometimes inhabited, buildings, often in chimneys, and even in dense conifers. They are famous for using church steeples for nesting, a fact reported in verse by William Cowper

A great frequenter of the church,

Where, bishoplike, he finds a perch,

And dormitory too.[28]

Nests are usually constructed by a mated pair blocking up the crevice by dropping sticks into it; the nest is then built atop the platform formed.[29] This behaviour has led to blocked chimneys and even nests, with the jackdaw present, crashing down into fireplaces.[30] Nest platforms can attain great size - John Mason Neale notes that a "Clerk was allowed by the Churchwarden to have for his own use all that the caddows had brought into the Tower: and he took home, at one time, two cart-loads of good firewood, besides a great quantity of rubbish which he threw away."[31]

Gilbert White, in his popular book The Natural History of Selborne, notes that jackdaws used to nest in crevices beneath the lintels of Stonehenge, and describes a curious example of jackdaws using rabbit burrows for nest sites.[11]

Nests are lined with hair, rags, bark, soil, and many other materials. Jackdaws nest in colonies and often close to rooks.[32] The eggs are smooth, glossy pale blue speckled with dark brown, measuring approximately 36 x 26 mm. Clutches of normally 4-5 eggs, are incubated by the female for 17-18 days and fledge after 28-35 days, when they are fed by both parents.[33]

Jackdaws hatch asynchronously and incubation begins before clutch completion, often leading to the death of the last-hatched young. The young which die in the nest do so quickly which minimises parental investment, and hence the brood size comes to fit the available food supply.[34]

Social behavior

The jackdaw is a highly sociable species outside of the breeding season, occurring in flocks that can contain hundreds of birds.[29]

Konrad Lorenz studied the complex social interactions that occur in groups of jackdaws and published his detailed observations of their social behavior in his book King Solomon's Ring. To study jackdaws, Lorenz put coloured rings on the legs of the jackdaws that lived around his house in Altenberg, Austria for identification, and he caged them in the winter because of their annual migration away from Austria. His book describes his observations on jackdaws' hierarchical group structure, in which the higher-ranking birds are dominant over lower ranked birds. The book also records his observations on jackdaws' strong male–female bonding; he noted that each bird of a pair both have about the same rank in the hierarchy, and that a low-ranked female jackdaw rocketed up the jackdaw social ladder when she became the mate of a high-ranking male.

Jackdaws have been observed sharing food and objects. The active giving of food is rare in primates, and in birds is found mainly in the context of parental care and courtship. Jackdaws show much higher levels of active giving than documented for chimpanzees. The function of this behaviour is not fully understood, although it has been found to be compatible with hypotheses of mutualism, reciprocity and harassment avoidance.[35]

Occasionally the flock makes 'mercy killings', in which a sick or injured bird is mobbed until it is killed.[29]

Cultural depictions and folklore

- In some cultures, a jackdaw on the roof is said to predict a new arrival; alternatively, a jackdaw settling on the roof of a house or flying down a chimney is an omen of death and coming across one is considered a bad omen.[36]

- A jackdaw standing on the vanes of a cathedral tower is meant to prognosticate rain. Czech superstition formerly held that if jackdaws are seen quarrelling, war will follow, and that jackdaws will not build nests at Sázava having been banished by Saint Procopius.[37]

- Ancient Greek authors tell how a jackdaw, being a social creature, may be caught with a dish of oil which it falls into while looking at its own reflection.[38]

- Pliny notes how the Thessalians, Illyrians and Lemnians cherished jackdaws for destroying grasshoppers' eggs. The Veneti are fabled to have bribed the jackdaws to spare their crops.[38]

- An ancient Greek and Roman adage runs "The swans will sing when the jackdaws are silent" meaning that educated or wise people will speak after foolish prattlers finally run out of talk.[39]

- The sentence "Jackdaws love my big sphinx of quartz" is a commonly used example of a pangram, (i.e. a sentence that contains all 26 letters of the English alphabet), while the sentence itself is only 31 letters long.[40]

External links

- Jackdaw videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Oiseaux Pictures

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta

- [2]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- BirdLife International (BI). 2008. Corvus monedula. In IUCN, 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ↑ BirdLife International, "Corvus monedula," In 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2008). Retrieved December 2, 2008.}

- ↑ (Latin) Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata.. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii)., 105.

- ↑ Simpson, D.P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary, 5, London: Cassell Ltd., 883. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- ↑ British Garden Birds: Jackdaw.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary: Jackdaw. 2nd ed. 1989.

- ↑ Swan, H. Kirke. A Dictionary of English and Folk-Names of British Birds, With their History, Meaning and first usage: and the Folk-lore, Weather-lore, Legends, etc., relating to the more familiar species. London: Witherby and Co. 1913.

- ↑ Wright, Joseph. The English Dialect Dictionary. Six volumes. London: Henry Frowde. 1898—1905.

- ↑ Swainson, Charles. Provincial Names and Folk Lore of British Birds. London: Trübner and Co., 1885.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Mullarney, Killian and Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (1999). Collins Bird Guide. Collins, 335. ISBN 0002197286.

- ↑ First recorded in Lydgate's Debate between the Horse, Goose and Sheep, c.1430, as "A clatering of chowhis", and then in Juliana Berners Book of St. Albans, c.1480, as "a Clateryng of choughes."

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 White, Gilbert (1833) The Natural Nistory of Selborne. London: N. Hailes, p. 163.

- ↑ [http://www.globaltwitcher.com/artspec.asp?thingid=26248 GlobalTwitcher.com: Eurasian Jackdaw Corvus monedula].

- ↑ Identification and occurrence of "Eastern" Jackdaws in the Netherlands.

- ↑ R.F. Porter, et al., Birds of the Middle East. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996: 405.

- ↑ Birdlife International. Data Zone. Species factsheet: Corvus monedula. Downloaded 23/11/2008.

- ↑ Identification and occurrence of "Eastern" Jackdaws in the Netherlands.

- ↑ Ghassan Ramadan-Jaradi, Thierry Bara and Mona Ramadan-Jaradi. "Revised checklist of the birds of Lebanon." Sandgrouse. 2008. 30(1):22-69.

- ↑ D.A. Murdoch and K.F. Betton. "A checklist of the birds of Syria." Sandgrouse: Supplement 2. 2008: 12.

- ↑ Mark Brazil. The Birds of East Asia. 2008.

- ↑ John L. Dunn and Jonanthan Alderfer, National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America. 5th ed. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006. p. 326

- ↑ The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Corvus monedula. Downloaded 23/11/2008.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Nathan J Emery, Amanda M Seed, Auguste M.P von Bayern, and Nicola S Clayton. "Cognitive adaptations of social bonding in birds." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: B Biological Sciences. 2007 April 29; 362(1480): 489–505.

- ↑ R.F. Porter, et al., Birds of the Middle East. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996: 405.

- ↑ John Gay. The Beggar's Opera. Edinburgh: A. Donaldson, 1760: 36.

- ↑ Tobias Smollett. Humphry Clinker. London: G. Routledge and Co., 1857: 78.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 J. D. Lockie "The Food and Feeding Behaviour of the Jackdaw, Rook and Carrion Crow." The Journal of Animal Ecology. 25:2 (Nov., 1956), pp. 421-428.

- ↑ Selvino R. de Kort, Nathan J. Emery and Nicola S. Clayton. "Food sharing in jackdaws, Corvus monedula: what, why and with whom?" Animal Behaviour 72:2 (August 2006): 297-304.

- ↑ The Poetical Works of William Cowper. Vol. 2. London: William Pickering, 1853. p. 336.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Wilmore, S. Bruce. Crows, jays, ravens and their relatives. London: David and Charles Ltd, 1977

- ↑ Greenoak, F. All the birds of the air; the names, lore and literature of British birds. London: Book Club Associates, 1979

- ↑ [John Mason Neale A Few Words to Parish Clerks and Sextons of Country Parishes. London: Joseph Masters, 1846.].

- ↑ British Garden Birds: Jackdaw.

- ↑ British Garden Birds: Jackdaw.

- ↑ David Wingfield Gibbons. 'Hatching Asynchrony Reduces Parental Investment in the Jackdaw.' Journal of Animal Ecology (1987) 53: 403-414.

- ↑ Frequent food- and object-sharing during jackdaw (Corvus monedula) socialisation, [1].

- ↑ Old superstitions: Jackdaw.

- ↑ Swainson, Charles. Provincial Names and Folk Lore of British Birds. London: Trübner and Co., 1885.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, A Glossary of Greek Birds. Oxford, 1895. p. 89.

- ↑ Collected Works of Erasmus: Adages: Ivi1 to Ix100. Translated by Roger A. Mynors. University of Toronto Press, 1989. p. 314.

- ↑ Fun with words

Further reading

Identification

Harrop, Andrew (2000) Identification of Jackdaw forms in northwestern Europe Birding World vol. 13, no. 7 pages 290-295

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.