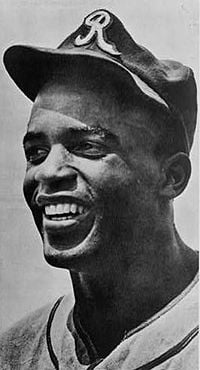

Jackie Robinson

| Jackie Robinson | |

|---|---|

| Position | 2B (748 games) 3B (356 games) 1B (197 games) OF (162 games) SS (1 game) |

| MLB Seasons | 10 |

| Team(s) | Brooklyn Dodgers |

| Debut | April 15, 1947 |

| Final Game | September 30, 1956 |

| Total Games | 1,382 batting 1,364 fielding |

| NL Pennants | 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955, 1956 |

| World Series Teams | 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955, 1956 |

| All-Star Teams | 1949 (2B), 1950 (2B), 1951 (2B), 1952 (2B), 1953 (3B), 1954 (OF) |

| Awards | Rookie of the Year (1947) |

| National League MVP (1949) | |

| NL batting leader (.342 - 1949) | |

| Baseball Hall of Fame (1962) | |

| Nickname | |

| "Jackie" | |

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 â October 24, 1972) became the first African-American Major League Baseball player of the modern era in 1947. His courage and conviction in breaking the so-called "color barrier" in Major League Baseball had an enormous impact on creating the conditions in which integration in all walks of life could be accepted by the masses. Robinson was a fierce competitor with a reputation for grace under fire, despite the racial taunts and bigotry that came his way. His courage and dignity helped America to overcome its legacy of racial prejudice.

Robinson's achievement has been recognized with the retirement by each Major League team of his uniform number, 42.

Before the Major Leagues

Born in Cairo, Georgia, Robinson moved with his mother and siblings to Pasadena, California in 1920, after his father deserted the family. At UCLA, he was a star in football, basketball, track, as well as baseball. He played with Kenny Washington, who would become one of the first black players in the National Football League in the early 1930s. Robinson also met his future wife Rachel at UCLA. His brother Matthew "Mack" Robinson (1912-2000) competed in the 1936 Summer Olympics, finishing second in the 200-meter sprint behind Jesse Owens.

After leaving UCLA his senior year, Robinson enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II. He trained with the segregated U.S. 761st Tank Battalion. Initially refused entry to Officer Candidate School, he fought and was eventually accepted, graduating as a second lieutenant. While training at Fort Hood, Texas, Robinson refused to go to the back of a bus. He was court-martialed for insubordination, and thus never shipped out to Europe with his unit. He received an honorable discharge in 1944, after being acquitted of all charges at the court-martial.

Jackie played baseball in 1944 for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro American League where he caught the eye of Clyde Sukeforth, a scout working for Branch Rickey.

The Dodgers

Branch Rickey was the club president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who harbored the secret goal of signing the Negro Leagues' top players to the team. Although there was no official ban on blacks in organized baseball, previous attempts at signing black ballplayers had been thwarted by league officials and rival clubs in the past, so Rickey operated undercover. His scouts were told that they were seeking players for a new all-black league Rickey was forming; not even they knew his true objective.

Robinson drew national attention when Rickey selected him from a list of promising candidates and signed him. In 1946, Robinson was assigned to play for the Dodgers' minor league affiliate in Montreal, the Montreal Royals. Although that season was very tiring emotionally for Robinson, it was also a spectacular success in a city that treated him with all the wild fan support that made the Canadian city a welcome refuge from the racial harassment he experienced elsewhere.

Robinson was a somewhat curious candidate to be the first black Major Leaguer in 60 years (see Moses Fleetwood Walker). Not only was he 27 (relatively old for a prospect), but he also had a fiery temperament. While some felt his more laid-back future teammate Roy Campanella might have been a better candidate to face the expected abuse, Rickey chose Robinson knowing that Jackie's outspoken nature would, in the long run, be more beneficial for the cause of black athletes than Campanella's relative docility. However, to ease the transition, Rickey asked Robinson to restrain his temper and his outspokenness for his first two years, and to moderate his natural reaction to the abuse. Aware of what was at stake, Robinson agreed.

Robinson's debut at first base with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947 (he batted 0 for 3), was one of the most eagerly-awaited events in baseball history, and one of the most profound in the history of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. During that first season, the abuse to which Robinson was subjected made him come close to losing his patience more than once. Many Dodgers were initially resistant to his presence. A group of Dodger players, mostly Southerners led by Dixie Walker, suggested they would strike rather than play alongside Robinson, but the mutiny ended when Dodger management informed the players they were welcome to find employment elsewhere. He did have the support of Kentucky-born shortstop Pee Wee Reese, who proved to be his closest comrade on the team. In a now legendary show of support, Reese put his arm around Robinsonâs shoulder to demonstrate his backing. The pair became a very effective defensive combination as a result. (Although he played his entire rookie year at first base, Robinson spent most of his career as a second baseman. He later played many games at third base and in the outfield.) Pittsburgh Pirate Hank Greenberg, the first major Jewish baseball star who experienced anti-Semitic abuse, also gave Robinson encouragement.

Throughout that first season, Robinson experienced considerable harassment from both players and fans. The Philadelphia Philliesâencouraged by manager Ben Chapmanâwere particularly abusive. In their April 22nd game against the Dodgers, they barracked him continually, calling him a "nigger" from the bench, telling him to "go back to the jungle." Rickey would later recall that "Chapman did more than anybody to unite the Dodgers. When he poured out that string of unconscionable abuse, he solidified and united 30 men." Baseball Commissioner A. B. "Happy" Chandler I admonished the Phillies but asked Robinson to pose for photographs with Chapman as a conciliatory gesture. To his credit, Robinson didn't refuse.

In Robinson's rookie season, he earned the major-league minimum salary of $5000. He played in 151 games, hit .297, and was the league leader in stolen bases with 29.

Robinson was awarded the Rookie of the Year award in 1947, and the Most Valuable Player award for the National League in 1949. He not only contributed to Brooklyn pennants in both years, but his determination and hustle helped keep the Dodgers in pennant races in both the 1950 and 1951 seasons. (The 1951 season must have been particularly galling for a competitor like Robinson. The Dodgers blew a large lead and lost the one game playoff on the famous "shot heard round the world" by Giant batter Bobby Thompson off Ralph Branca.) In 1955, though clearly on the downside of his career, Robinson would play a prominent role in leading the Brooklyn Dodgers to their first and only World Series championship in Brooklyn, in a seven game victory over the New York Yankees.

Robinson's Major League career was fairly short. He did not enter the majors until he was 28, and was often injured as he aged. But in his prime, he was respected by every opposing team in the league.

After the 1956 season, Robinson was sold by the Dodgers to the New York Giants (soon to become the San Francisco Giants). Rather than report to the Giants, however, Robinson chose to retire at age 37. This sale further added to Robinson's growing disillusionment with the Dodgers, and in particular Walter O'Malley (who had forced Rickey out as General Manager) and manager Walter Alston.

Robinson was an exceptionally talented and disciplined hitter, with a career average of .311 and a very high walks to strikeouts ratio. He played several defensive positions extremely well and was the most aggressive and successful baserunner of his era; he was among the few players to "steal home" frequently, doing so at least 19 documented times, including a famous steal of home in the 1955 World Series. Robinson's overall talent was such that he is often cited as among the best players of his era. His speed and physical presence often disrupted the concentration of pitchers, catchers, and middle infielders. It is also frequently claimed that Robinson was one of the most intelligent baseball players ever, a claim that is well supported by his home plate discipline and defensive prowess. Robinson was among the best players of his era, but his lasting contribution to the game will remain his grace under enormous pressure in breaking baseballâs so-called color barrier. In one of his most famous quotes, he said "I'm not concerned with your liking or disliking meâŚall I ask is that you respect me as a human being."

Post-Dodgers

Robinson retired from the game on January 5, 1957. He had wanted to manage or coach in the major leagues, but received no offers. He became a vice-president for the Chock Full O' Nuts Corporation instead, and served on the board of the NAACP till 1967, when he resigned because of the movement's lack of younger voices. In 1960, he involved himself in the presidential election, campaigning for Hubert Humphrey. Then, after meeting both Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy, Robinson endorsed Nixon, citing his record on civil rights. He campaigned diligently for Humphrey in 1968. After Nixon was elected in 1968, Robinson wrote that he regretted the previous endorsement.

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, his first year of eligibility, becoming the first African-American so honored. On June 4, 1972 the Dodgers retired his uniform number 42 alongside Roy Campanella (39) and Sandy Koufax (32).

Robinson made his final public appearance on October 14, 1972, before Game two of the World Series in Cincinnati. He used this opportunity to express his desire to see a black manager hired by a major league baseball team. This wish was granted two years later, following the 1974 season, when the Cleveland Indians gave their managerial post to Frank Robinson, a Hall-of-Fame-bound slugger who was then still an active player, and no relation to Jackie Robinson. At the press conference announcing his hiring, Frank expressed his regret that Jackie had not lived to see the moment (Jackie died October 24, 1972). In 1981, four years after being fired as Indians manager, Frank Robinson was hired as the first black manager of a National League team, the San Francisco Giants. As of the conclusion of the 2005 season, five teams had black or Hispanic managers, including Frank Robinson, now with the Washington Nationals, and 13 of the 30 teams had hired one at some point in their history.

Robinson's final few years were marked by tragedy. In 1971, his elder son, Jackie, Jr., was killed in an automobile accident. The diabetes that plagued him in middle age had left him virtually blind and contributed to severe heart troubles. Jackie Robinson died in Stamford, Connecticut on October 24, 1972, and was interred in the Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

In 1997 (the 50th anniversary of his major league debut), his number (42) was retired by all Major League Baseball teams. In 2004, Major League Baseball designated that April 15th of each year would be marked as "Jackie Robinson Day" at all ballparks.

On October 29, 2003, the United States Congress posthumously awarded Robinson the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest award the Congress can bestow. Robinson's widow accepted the award in a ceremony in the Capital Rotunda on March 2, 2005.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Rampersad, Arnold. Jackie Robinson: A Biography. Ballantine Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0345426550

- Robinson, Jackie, and Alfred Duckett. I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson. Ecco, 2003. ISBN 978-0060555979

- Robinson, Sharon. Promises to Keep: How Jackie Robinson Changed America. Scholastic Inc., 2004. ISBN 978-0439425926

- Tygiel, Jules. Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0195339284

External links

All links retrieved December 13, 2024.

- Jackie Robinson Baseball Reference.com

- Jackie Robinson Stats Baseball Almanac

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.