Difference between revisions of "Holy Chalice" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) m |

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Image:Methodistcommunion2.jpg|thumb|220px|This modern celebration of the Eucharist retains the original elements of the ''Last Supper'', the bread and the chalice. The priest uses the words of Jesus.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[Christian tradition]] the '''Holy Chalice''' is the vessel which Jesus used at the [[Last Supper]] to serve the wine. The ''[[Gospel of Matthew]]'' says: | ||

| + | :"And he took a cup and when he had given thanks he gave it to them saying 'Drink this, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until I drink it new with you in my Father's kingdom." | ||

| + | |||

| + | This incident, traditionally known as the [[Last Supper]], is also described by the gospel writers, [[Mark the Evangelist|Mark]] and [[Luke the Evangelist|Luke]], and by the [[Apostle Paul]] in I Corinthians. With the preceding description of the breaking of bread, it is the foundation for the tradition of the [[Eucharist]] or [[Holy Communion]], celebrated regularly in many Christian churches. The [[Bible]] makes no mention of the cup except within the context of the Last Supper and gives no significance whatever to the object itself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | St. [[John Chrysostom]], (347-407 C.E.), in his homily on ''[[Book of Matthew|Matthew]]'' asserted: | ||

| + | :The table was not of silver, the chalice was not of gold in which Christ gave His blood to His disciples to drink, and yet everything there was precious and truly fit to inspire awe. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Herbert Thurston in the ''[[Catholic Encyclopedia]]'' 1908 concluded that: | ||

| + | :No reliable tradition has been preserved to us regarding the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper. In the sixth and seventh centuries pilgrims to Jerusalem were led to believe that the actual chalice was still venerated in the church of the Holy Sepulchre, having within it the sponge which was presented to Our Saviour on Calvary. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Catholic tradition== | ||

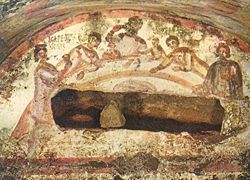

| + | [[Image:Agape feast 03.jpg|thumb|250px|Early Christians celebrating Communion at an [[Agape]] Feast, from the [[Catacomb]] of Ss. Peter and Marcellinus.]] | ||

| + | According to [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholic]] tradition, the cup of the [[Last Supper]], known as the ''Holy Chalice'', was safeguarded by [[Saint Peter]], who used it to say [[Mass]], and took it with him when he travelled to [[Rome]]. After Peter's death, tradition states that the cup was passed on to his successor popes, until [[Sixtus II]] in 258 C.E., when Christians were being persecuted by Emperor [[Valerian]], and the Romans demanded that relics be turned over to the government. Sixtus gave the cup to his deacon, [[Saint Lawrence]], who passed it to a Spanish soldier, Proselius, with instructions to take it to safety in Lawrence's home country of Spain. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The continuing tradition of the association of the ''Holy Chalice'' with Spain is that it was safeguarded by a series of Spanish monarchs, including King [[Alfonso]] in 1200 C.E. At one point when he needed money for a military campaign, Alfonso borrowed from the [[Cathedral of Valencia]], using the Chalice as collateral. When he defaulted on the loan, the relic became the property of the church (see Holy Chalice of Valencia, below). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Association with the "Holy Grail"== | ||

| + | There is an entirely different and pervasive tradition concerning the cup of the ''Last Supper''. In this highly muddled though better-known version, the vessel is known as [[Holy Grail]]. In this legend, the cup was used to collect and store the blood of Christ at the Crucifixion. This conflicts with the notion that Peter might have used the cup of the ''[[Last Supper]]'' to celebrate the [[Mass]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although the traditions of the ''Holy Chalice'' and the '' Holy Grail'' seem irreconcilable, there is an underlying concept. Since in [[Catholic]] theology, the wine consecrated in the mass becomes the true [[blood of Christ]], both of these seemingly conflicting traditions emphasize the vessel as a cup which holds the blood of [[Jesus Christ]], either in [[sacramental]] or literal form. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Oral tradition]], poems and bardic tales combined the stories of the ''Holy Chalice'' and the [[Holy Grail]]. A mix of fact and fiction incorporated elements around [[Crusaders]], [[knights]] and [[King Arthur]], as well as being blended with [[Celt]]ic and [[Germany|German]] legends. In 1485 C.E., Sir [[Thomas Malory]], combined many of the traditions in his ''King Arthur and the Knights'' (''Le Morte d'Arthur''), in which the fictional character of [[Sir Galahad]] goes on the quest for the Holy Grail. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Iconography of the Holy Chalice== | ||

| + | [[Image:Gotland-Oeja Kyrka Passionszyklus 02.jpg|thumb|250px|Two episodes from the Passion-cycle murals of Öja Church, [[Gotland]].]] | ||

| + | The [[icon]]ic significance of the Chalice grew during the Early Middle Ages. In the fourteenth-century frescoes of the church at the Öja, [[Gotland]] ''(illustration, right)'', when Jesus prays in the Garden of Gethsemane, it is a prefigured apparition of the Holy Chalice that stands at the top of the mountain. Together with the halo-enveloped Hand of God and the haloed figure of Jesus, the halo image atop the chalice, as if of a consecrated communion wafer, completes the Trinity by embodying the Holy Spirit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Four medieval relics== | ||

| + | During the Middle Ages, three major contenders for the position of Holy Chalice stood out from the rest, one in [[Jerusalem]], one in [[Genoa]] and the third in [[Valencia, Spain|Valencia]]. A fourth medieval cup was briefly touted as the Holy Chalice when it was discovered in the early 20th century; it is known as the ''Antioch Chalice'' and is in the [[Metropolitan Museum]], [[New York]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Jerusalem Chalice=== | ||

| + | The earliest record of a chalice from the Last Supper is the account of [[Arculf]] a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon pilgrim who described it in ''De locis sanctis'' as being located in a reliquary in a chapel near [[Jerusalem]], between the basilica of [[Golgotha]] and the Martyrium. He described it as a two-handled silver chalice with the measure of a [[Gaul]]ish [[pint]]. Arculf kissed his hand and reached through an opening of the perforated lid of the reliquary to touch the chalice. He said that the people of the city flocked to it with great veneration. (Arculf also saw the [[Holy Lance]] in the porch of the basilica of Constantine.) This is the only mention of the ''Holy Chalice'' being situated in the Holy Land. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Genoa Chalice=== | ||

| + | Of two vessels that survive today, one is at [[Genoa]], in the cathedral. The hexagonal vessel is known as the ''sacro catino'', the holy basin. Traditionally said to be carved from [[emerald]], it is in fact a green Egyptian glass dish, about eighteen inches (37 cm) across. It was sent to Paris after [[Napoleon]]’s conquest of Italy, and was returned broken, which identified the emerald as glass. Its origin is uncertain; according to [[William of Tyre]], writing in about 1170, it was found in the mosque at [[Caesarea Maritima|Caesarea]] in 1101: "a vase of brilliant green shaped like a bowl." The Genoese, believing that it was of emerald, accepted it in lieu of a large sum of money. An alternative story in a Spanish chronicle says that it was found when [[Alfonso VII of Castile]] captured [[Almería]] from the Moors in 1147 with Genoese help, ''un vaso de piedra esmeralda que era tamanno como una escudiella'', "a vase carved from emerald which was like a dish." The Genoese said that this was the only thing they wanted from the sack of Almería. The identification of the ''sacro catino'' with the ''Holy Chalice'' is not made until later, however, by [[Jacobus de Voragine]] in his chronicle of Genoa, written at the close of the 13th century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Valencia Chalice=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Juan de Juanes 002.jpg|thumb|270px|The cup depicted here by Juan Juanes in the late 16th century is the ''Chalice of Valencia''.]] | ||

| + | The other surviving ''Holy Chalice'' vessel is the ''santo cáliz'', an [[agate]] cup in the [[Saint Mary of Valencia Cathedral|Cathedral of Valencia]]. It is preserved in a chapel consecrated to it, where it still attracts the faithful on pilgrimage. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The piece is a hemispherical cup made of dark red [[agate]] about 9 centimeters/ 3.5 inches in diameter and about 17 centimeters/ 7 inches high, including the base which has been made of an inverted cup of [[chalcedony]]. The upper agate portion, without the base, fits a description by [[Saint Jerome]]. The lower part contains Arabic inscriptions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After an inspection in 1960, the Spanish archaeologist Antonio Beltrán asserted that the cup was produced in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the 4th century B.C.E. and the 1st century C.E. The surface has not been dated by microscopic scanning to assess [[recrystallization]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''The Chalice of Valencia'' comes complete with a certificate of authenticity, an inventory list on vellum, said to date from 262 C.E., that accompanied a lost letter of which details state-sponsored Roman persecution of Christians that forces the church to split up its treasury and hide it with members, specifically the deacon [[Saint Lawrence]]. It goes on to enumerate all precious items. The physical properties of the Holy Chalice are described and it is stated the vessel had been used to celebrate Mass by the early [[Pope]]s succeeding [[Saint Peter]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first explicit inventory reference to the present ''Chalice of Valencia'' dates from 1134, an inventory of the treasury of the monastery of San Juan de la Peña drawn up by Don Carreras Ramírez, Canon of Zaragoza, December 14, 1134: "En un arca de marfil está el Cáliz en que Cristo N. Señor consagró su sangre, el cual envió [[Saint Lawrence|S. Lorenzo]] a su patria, Huesca." According to the wording of this document, the Chalice is described as the vessel in which "Christ Our Lord consigned his blood." <ref> While this appears to refer to an association with the [[Holy Grail]], during the [[Last Supper]] Christ referred to the wine as "My blood which is poured out for many." Moreover, with the [[Roman Catholic]] [[doctrine]] of [[transubstantiation]], the wine used during the [[Eucharist]] is considered to become truly the blood of Christ. For the subsequent separate development of a Grail myth see [[Holy Grail]]. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Reference to the chalice is made in 1399, when it was given by the monastery of [[San Juan de la Peña]] to king [[Martin I of Aragon]] in exchange for a gold cup. By the end of the century a provenance for the chalice can be detected, by which [[Saint Peter]] had brought it to Rome. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Pope John Paul II]] himself celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice in Valencia in November 1982, causing some uproar both in [[skeptic]] circles and in the circles that hoped he would say ''accipiens et hunc praeclarum Calicem'' ("this most famous chalice") in lieu of the ordinary words of the [[Mass]] taken from ''Matthew'' 26:27). For some people, the authenticity of the Chalice of Valencia failed to receive papal blessing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In July 2006, at the closing Mass of the 5th World Meeting of Families in Valencia, [[Pope Benedict XVI]] also celebrated with the Holy Chalice, on this occasion saying "this most famous chalice," words in the [[Roman Canon]] said to have been used for the first popes until 4th century in Rome, and supporting in this way the tradition of ''the Holy Chalice of Valencia''. This artifact has seemingly never been accredited with any [[supernatural]] powers, which [[superstition]] apparently confines to other relics such as the [[Holy Grail]], the [[Spear of Destiny]] and the [[True Cross]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In ''Saint Laurence and the Holy Grail'', Janice Bennett gives an account of the chalice's history, carried on [[Saint Peter]]'s journey to Rome, entrusted by [[Pope Sixtus II]] to [[Saint Lawrence]] in the third century, sent to Huesca in Spain when the Hispanic saint was martyred on a gridiron during the Valerian persecution in Rome in 258 C.E., sent to the Pyrenees for safekeeping, where it passed from monastery to monastery, in accordance with all the claims to former possession of the Chalice, and venerated by the monks of the Monastery of San Juan de la Peña. Emerging there into the light of history, the monastery's agate cup was acquired by King [[Martin I of Aragon]] in 1399 who kept it at Zaragoza. After his death, King [[Alfonso V of Aragón]] brought it to Valencia, where it has remained. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bennett presents as historical evidence a 6th-century manuscript Latin ''Vita'' written by Donato, an Augustinian monk who founded a monastery in the area of Valencia, which contains circumstantial details of the life of Saint Laurence and details surrounding the transfer of the Chalice to Spain. The original manuscript does not exist, but a 17th-century Spanish translation entitled "Life and Martyrdom of the Glorious Spaniard St. Laurence" is in a monastery in Valencia. The main source for the life of St. Laurence, the poem ''Peristephanon'' by the 5th-century poet [[Prudentius]], does not mention the Chalice that was later said to have passed through his hands. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1960 the Spanish archeologist Antonio Beltrán studied the Chalice and concluded: "Archeology supports and definitively confirms the historical authenticity." "Everyone in Spain believes it is the cup," Bennett said to a reporter from the ''Denver Catholic Register''. "You can see it every day that the chapel is open." | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:The Antioch Chalice, first half of 6th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg|thumb|The Antioch Chalice, first half of 6th century, [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]]]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Antioch Chalice=== | ||

| + | The silver gilt object originally identified as an early Christian chalice is in the collection of the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]] in [[New York City]], It was apparently made at [[Antioch]] in the early 6th century and is of double-cup construction, with an outer shell of cast-metal open work enclosing a plain silver inner cup. When it was first recovered in Antioch just before [[World War I]], it was touted as the Holy Chalice, an identification the Metropolitan Museum characterizes as "ambitious." It is no longer identified as a chalice, having been identified by experts at Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, believed to be a hanging lamp, of a style of the 6th century. It appears that its support rings have been removed and the lamp reshaped with a base. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | {{reflist}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * Bennett, Janice, ''Saint Laurence and the Holy Grail'' (self-published through the Catholic Ignatius Press), 2004. | ||

| + | * Eisen, Gustavus A., ''The great chalice of Antioch'', New York, Fahim Kouchakji, 1933. | ||

| + | * Eisen, Gustavus A., ''The great chalice of Antioch, on which are depicted in sculpture the earliest known portraits of Christ, apostles and evangelists'', New York, Kouchakji frères, 1923. | ||

| + | * Salvador Antuñano Alea, ''Truth and Symbolism of Holy Grail: Revelations Surrounding Valencia's Sacred Chalice'' (in Spanish, with a prologue by Archbishop Agustin Garcia Gasco of Valencia), 1999 | ||

| + | * Strzygowski, Josef, ''L'ancien art chrétien de Syrie'', Paris, E. de Boccard, 1936. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External Links== | ||

| + | *[http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Rhodes/3946/santocaliz The Grail of the Last Supper]:with a chronicle of the supposed movements of the Santo Caliz. Retrieved August 10, 2008. | ||

| + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03561a.htm ''Catholic Encyclopedia'':] Chalice (illustration of the Holy Chalice of Valencia) Retrieved August 10, 2008. | ||

| + | *[http://www.archden.org/dcr/archive/20020911/2002091121ln.htm Report in the ''Denver Catholic Register''] Retrieved August 10, 2008. | ||

| + | *[http://www.ad2000.com.au/articles/1999/oct1999p12_297.html "Spanish academic revives speculation about authenticity of the Holy Grail"] Retrieved August 10, 2008. | ||

| + | *[http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ho/06/waa/hod_50.4.htm Metropolitan Museum:] Antioch Chalice. Retrieved August 10, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

[[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

[[Category:Religion]] | [[Category:Religion]] | ||

[[Category:Christianity]] | [[Category:Christianity]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{credits|227954066}} | ||

Revision as of 04:52, 10 August 2008

In Christian tradition the Holy Chalice is the vessel which Jesus used at the Last Supper to serve the wine. The Gospel of Matthew says:

- "And he took a cup and when he had given thanks he gave it to them saying 'Drink this, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until I drink it new with you in my Father's kingdom."

This incident, traditionally known as the Last Supper, is also described by the gospel writers, Mark and Luke, and by the Apostle Paul in I Corinthians. With the preceding description of the breaking of bread, it is the foundation for the tradition of the Eucharist or Holy Communion, celebrated regularly in many Christian churches. The Bible makes no mention of the cup except within the context of the Last Supper and gives no significance whatever to the object itself.

St. John Chrysostom, (347-407 C.E.), in his homily on Matthew asserted:

- The table was not of silver, the chalice was not of gold in which Christ gave His blood to His disciples to drink, and yet everything there was precious and truly fit to inspire awe.

Herbert Thurston in the Catholic Encyclopedia 1908 concluded that:

- No reliable tradition has been preserved to us regarding the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper. In the sixth and seventh centuries pilgrims to Jerusalem were led to believe that the actual chalice was still venerated in the church of the Holy Sepulchre, having within it the sponge which was presented to Our Saviour on Calvary.

Catholic tradition

According to Roman Catholic tradition, the cup of the Last Supper, known as the Holy Chalice, was safeguarded by Saint Peter, who used it to say Mass, and took it with him when he travelled to Rome. After Peter's death, tradition states that the cup was passed on to his successor popes, until Sixtus II in 258 C.E., when Christians were being persecuted by Emperor Valerian, and the Romans demanded that relics be turned over to the government. Sixtus gave the cup to his deacon, Saint Lawrence, who passed it to a Spanish soldier, Proselius, with instructions to take it to safety in Lawrence's home country of Spain.

The continuing tradition of the association of the Holy Chalice with Spain is that it was safeguarded by a series of Spanish monarchs, including King Alfonso in 1200 C.E. At one point when he needed money for a military campaign, Alfonso borrowed from the Cathedral of Valencia, using the Chalice as collateral. When he defaulted on the loan, the relic became the property of the church (see Holy Chalice of Valencia, below).

Association with the "Holy Grail"

There is an entirely different and pervasive tradition concerning the cup of the Last Supper. In this highly muddled though better-known version, the vessel is known as Holy Grail. In this legend, the cup was used to collect and store the blood of Christ at the Crucifixion. This conflicts with the notion that Peter might have used the cup of the Last Supper to celebrate the Mass.

Although the traditions of the Holy Chalice and the Holy Grail seem irreconcilable, there is an underlying concept. Since in Catholic theology, the wine consecrated in the mass becomes the true blood of Christ, both of these seemingly conflicting traditions emphasize the vessel as a cup which holds the blood of Jesus Christ, either in sacramental or literal form.

Oral tradition, poems and bardic tales combined the stories of the Holy Chalice and the Holy Grail. A mix of fact and fiction incorporated elements around Crusaders, knights and King Arthur, as well as being blended with Celtic and German legends. In 1485 C.E., Sir Thomas Malory, combined many of the traditions in his King Arthur and the Knights (Le Morte d'Arthur), in which the fictional character of Sir Galahad goes on the quest for the Holy Grail.

Iconography of the Holy Chalice

The iconic significance of the Chalice grew during the Early Middle Ages. In the fourteenth-century frescoes of the church at the Öja, Gotland (illustration, right), when Jesus prays in the Garden of Gethsemane, it is a prefigured apparition of the Holy Chalice that stands at the top of the mountain. Together with the halo-enveloped Hand of God and the haloed figure of Jesus, the halo image atop the chalice, as if of a consecrated communion wafer, completes the Trinity by embodying the Holy Spirit.

Four medieval relics

During the Middle Ages, three major contenders for the position of Holy Chalice stood out from the rest, one in Jerusalem, one in Genoa and the third in Valencia. A fourth medieval cup was briefly touted as the Holy Chalice when it was discovered in the early 20th century; it is known as the Antioch Chalice and is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

The Jerusalem Chalice

The earliest record of a chalice from the Last Supper is the account of Arculf a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon pilgrim who described it in De locis sanctis as being located in a reliquary in a chapel near Jerusalem, between the basilica of Golgotha and the Martyrium. He described it as a two-handled silver chalice with the measure of a Gaulish pint. Arculf kissed his hand and reached through an opening of the perforated lid of the reliquary to touch the chalice. He said that the people of the city flocked to it with great veneration. (Arculf also saw the Holy Lance in the porch of the basilica of Constantine.) This is the only mention of the Holy Chalice being situated in the Holy Land.

The Genoa Chalice

Of two vessels that survive today, one is at Genoa, in the cathedral. The hexagonal vessel is known as the sacro catino, the holy basin. Traditionally said to be carved from emerald, it is in fact a green Egyptian glass dish, about eighteen inches (37 cm) across. It was sent to Paris after Napoleon’s conquest of Italy, and was returned broken, which identified the emerald as glass. Its origin is uncertain; according to William of Tyre, writing in about 1170, it was found in the mosque at Caesarea in 1101: "a vase of brilliant green shaped like a bowl." The Genoese, believing that it was of emerald, accepted it in lieu of a large sum of money. An alternative story in a Spanish chronicle says that it was found when Alfonso VII of Castile captured Almería from the Moors in 1147 with Genoese help, un vaso de piedra esmeralda que era tamanno como una escudiella, "a vase carved from emerald which was like a dish." The Genoese said that this was the only thing they wanted from the sack of Almería. The identification of the sacro catino with the Holy Chalice is not made until later, however, by Jacobus de Voragine in his chronicle of Genoa, written at the close of the 13th century.

The Valencia Chalice

The other surviving Holy Chalice vessel is the santo cáliz, an agate cup in the Cathedral of Valencia. It is preserved in a chapel consecrated to it, where it still attracts the faithful on pilgrimage.

The piece is a hemispherical cup made of dark red agate about 9 centimeters/ 3.5 inches in diameter and about 17 centimeters/ 7 inches high, including the base which has been made of an inverted cup of chalcedony. The upper agate portion, without the base, fits a description by Saint Jerome. The lower part contains Arabic inscriptions.

After an inspection in 1960, the Spanish archaeologist Antonio Beltrán asserted that the cup was produced in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the 4th century B.C.E. and the 1st century C.E. The surface has not been dated by microscopic scanning to assess recrystallization.

The Chalice of Valencia comes complete with a certificate of authenticity, an inventory list on vellum, said to date from 262 C.E., that accompanied a lost letter of which details state-sponsored Roman persecution of Christians that forces the church to split up its treasury and hide it with members, specifically the deacon Saint Lawrence. It goes on to enumerate all precious items. The physical properties of the Holy Chalice are described and it is stated the vessel had been used to celebrate Mass by the early Popes succeeding Saint Peter.

The first explicit inventory reference to the present Chalice of Valencia dates from 1134, an inventory of the treasury of the monastery of San Juan de la Peña drawn up by Don Carreras Ramírez, Canon of Zaragoza, December 14, 1134: "En un arca de marfil está el Cáliz en que Cristo N. Señor consagró su sangre, el cual envió S. Lorenzo a su patria, Huesca." According to the wording of this document, the Chalice is described as the vessel in which "Christ Our Lord consigned his blood." [1]

Reference to the chalice is made in 1399, when it was given by the monastery of San Juan de la Peña to king Martin I of Aragon in exchange for a gold cup. By the end of the century a provenance for the chalice can be detected, by which Saint Peter had brought it to Rome.

Pope John Paul II himself celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice in Valencia in November 1982, causing some uproar both in skeptic circles and in the circles that hoped he would say accipiens et hunc praeclarum Calicem ("this most famous chalice") in lieu of the ordinary words of the Mass taken from Matthew 26:27). For some people, the authenticity of the Chalice of Valencia failed to receive papal blessing.

In July 2006, at the closing Mass of the 5th World Meeting of Families in Valencia, Pope Benedict XVI also celebrated with the Holy Chalice, on this occasion saying "this most famous chalice," words in the Roman Canon said to have been used for the first popes until 4th century in Rome, and supporting in this way the tradition of the Holy Chalice of Valencia. This artifact has seemingly never been accredited with any supernatural powers, which superstition apparently confines to other relics such as the Holy Grail, the Spear of Destiny and the True Cross.

In Saint Laurence and the Holy Grail, Janice Bennett gives an account of the chalice's history, carried on Saint Peter's journey to Rome, entrusted by Pope Sixtus II to Saint Lawrence in the third century, sent to Huesca in Spain when the Hispanic saint was martyred on a gridiron during the Valerian persecution in Rome in 258 C.E., sent to the Pyrenees for safekeeping, where it passed from monastery to monastery, in accordance with all the claims to former possession of the Chalice, and venerated by the monks of the Monastery of San Juan de la Peña. Emerging there into the light of history, the monastery's agate cup was acquired by King Martin I of Aragon in 1399 who kept it at Zaragoza. After his death, King Alfonso V of Aragón brought it to Valencia, where it has remained.

Bennett presents as historical evidence a 6th-century manuscript Latin Vita written by Donato, an Augustinian monk who founded a monastery in the area of Valencia, which contains circumstantial details of the life of Saint Laurence and details surrounding the transfer of the Chalice to Spain. The original manuscript does not exist, but a 17th-century Spanish translation entitled "Life and Martyrdom of the Glorious Spaniard St. Laurence" is in a monastery in Valencia. The main source for the life of St. Laurence, the poem Peristephanon by the 5th-century poet Prudentius, does not mention the Chalice that was later said to have passed through his hands.

In 1960 the Spanish archeologist Antonio Beltrán studied the Chalice and concluded: "Archeology supports and definitively confirms the historical authenticity." "Everyone in Spain believes it is the cup," Bennett said to a reporter from the Denver Catholic Register. "You can see it every day that the chapel is open."

The Antioch Chalice

The silver gilt object originally identified as an early Christian chalice is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, It was apparently made at Antioch in the early 6th century and is of double-cup construction, with an outer shell of cast-metal open work enclosing a plain silver inner cup. When it was first recovered in Antioch just before World War I, it was touted as the Holy Chalice, an identification the Metropolitan Museum characterizes as "ambitious." It is no longer identified as a chalice, having been identified by experts at Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, believed to be a hanging lamp, of a style of the 6th century. It appears that its support rings have been removed and the lamp reshaped with a base.

Notes

- ↑ While this appears to refer to an association with the Holy Grail, during the Last Supper Christ referred to the wine as "My blood which is poured out for many." Moreover, with the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, the wine used during the Eucharist is considered to become truly the blood of Christ. For the subsequent separate development of a Grail myth see Holy Grail.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, Janice, Saint Laurence and the Holy Grail (self-published through the Catholic Ignatius Press), 2004.

- Eisen, Gustavus A., The great chalice of Antioch, New York, Fahim Kouchakji, 1933.

- Eisen, Gustavus A., The great chalice of Antioch, on which are depicted in sculpture the earliest known portraits of Christ, apostles and evangelists, New York, Kouchakji frères, 1923.

- Salvador Antuñano Alea, Truth and Symbolism of Holy Grail: Revelations Surrounding Valencia's Sacred Chalice (in Spanish, with a prologue by Archbishop Agustin Garcia Gasco of Valencia), 1999

- Strzygowski, Josef, L'ancien art chrétien de Syrie, Paris, E. de Boccard, 1936.

External Links

- The Grail of the Last Supper:with a chronicle of the supposed movements of the Santo Caliz. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Chalice (illustration of the Holy Chalice of Valencia) Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- Report in the Denver Catholic Register Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- "Spanish academic revives speculation about authenticity of the Holy Grail" Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- Metropolitan Museum: Antioch Chalice. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.