The Last Supper was the final meal Jesus shared with his Twelve Apostles before his death, according to Christian tradition. Described in the synoptic gospels as a Passover Seder in which Jesus instituted the Eucharist, it plays a major role in Christian theology and has been the subject of numerous works of art, most famously by Leonardo da Vinci.

Also known as the Lord's Supper, the event is first described by Saint Paul in his first letter to the Corinthians, in which he says that he received Jesus' words at the supper through a personal revelation. In the gospels' description of the Last Supper, Jesus is depicted as predicting Judas Iscariot's betrayal, Peter's three-fold denial, and Jesus' abandonment by the rest of his disciples. While the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are in general agreement about the events of the Last Supper, the Gospel of John presents it quite differently, omitting the institution of the Eucharist, adding the scene of Jesus washing his disciples' feet, and describing it as something other than a Passover Seder.

The Last Supper is particularly important in Christian tradition as the moment when Jesus instituted the tradition of Holy Communion. After the Protestant Reformation, various interpretations of the meaning of this tradition have emerged. Since the nineteenth century, critical scholarship has questioned the historicity of the Last Supper, suggesting that it is largely the product of the developing sacramental tradition of the early Christian church.

New Testament

Earliest Description

The first written description of the Last Supper is that of the Apostle Paul in Chapter 11 of his first letter to the Corinthians:

For I received from the Lord what I also passed on to you: The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, "This is my body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of me." In the same way, after supper he took the cup, saying, "This cup is the new covenant in my blood; do this, whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me." For whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord's death until he comes. (1 Corinthians 11:23-26)

Paul indicates he learned of the ceremony directly from the Lord, through a revelation. The synoptic gospels present more details, while repeating many of the words given by Paul.

The fact that Paul claims to have learned what happened at the Last Supper through a personal revelation leads modern scholars to speculate that the tradition of the Last Supper may be based on what Paul believed to have happened, rather than on an oral tradition passed on by eye witnesses. Theologically, Paul placed strong emphasis on the atoning death and resurrection of Jesus as being God's intent in sending Jesus the Messiah. Paul's understanding of the Last Supper is thought by critical scholars to have been influenced by this belief. In this theory, the gospel writers relied on the tradition established by Paul, which they later incorporated into their texts. Traditionally, however, the Christian churches have taught that the description of the Last Supper given in the gospels is what actually happened.

Gospel accounts

According to the synoptic gospels, Jesus had instructed a pair of unnamed disciples to go to Jerusalem to meet a man carrying a jar of water who would lead them to a house, where they were to ask for the room, specified as being the "upper room." There, they were to prepare the Passover meal.

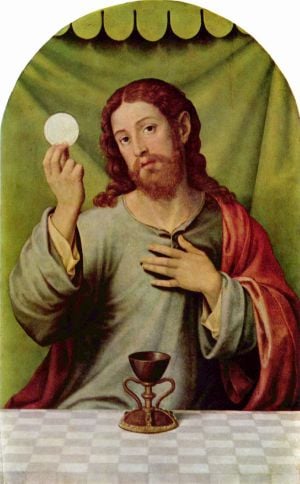

In the course of the meal‚ÄĒaccording to Paul and the synoptic gospels, but not the Gospel of John‚ÄĒJesus divides up some bread, says a prayer, and hands the pieces of bread to his disciples, saying "this is my body." He then takes a cup of wine, offers another prayer, and hands it around, saying "this is my blood of the everlasting covenant, which is poured for many." Finally, according to Paul and Luke, he tells the disciples "do this in memory of me." This event has been regarded by Christians of most denominations as the institution of the Eucharist or Holy Communion.

According to Matthew and Mark, the supper then concludes with the singing of a hymn, as was the tradition at Passover, and Jesus and his disciples then go the Mount of Olives. Luke, however, extends his description of the supper to include Jesus' prediction of his betrayal and other material (see below).

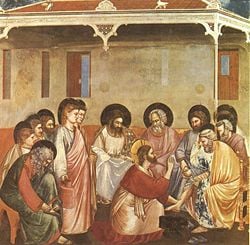

The account in John's gospel differs considerably from the above description, in which the meal is clearly a Passover Seder. In John 13, the meal takes place "just before the Passover Feast." Here, Jesus famously washes his disciples' feet, an event that is not mentioned in the other accounts. Some of the other details make it clear that this is the same meal that the synoptic Gospels describe, such as Jesus' identification of Judas Iscariot as his betrayer and the prediction of Peter's denial (John 13:21-38). However, there is no partaking of bread and wine to institute the Eucharist. In John's Gospel, Jesus has indicated from the beginning of his ministry that his disciples must "eat my body" and "drink my blood" to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

According to the synoptic accounts, Jesus now reveals that one of his Apostles would betray him, with Luke describing this as happening at the supper, while Matthew and Mark place it on the Mount of Olives. Despite assertions of each apostle that it would not be he, Jesus reiterates his prediction and goes on to place a curse on the betrayer, saying: "Woe to the man who betrays the Son of Man! It would be better for him if he had not been born." (Mark 14:20-21) Neither the Gospel of Mark nor the Gospel of Luke identifies the betrayer yet, but the Gospel of Matthew (26:23-26:25) and The Gospel of John (John 13:26-13:27) specify that it is Judas Iscariot.

All four canonical gospels recount that Jesus knew the apostles would "fall away." Simon Peter insists that he will not abandon Jesus even if the others do, but Jesus declares that Peter will deny Jesus three times before the cock had crowed twice. Peter insists that he will remain true even if it means death, and the other apostles are described as stating the same about themselves.

After the meal, according to John (but not in synoptics), Jesus gives a long sermon to the disciples, often described as his "farewell discourse." Luke adds a remarkable passage in which Jesus avowedly contradicts his early teaching and commands his disciples to buy weapons:

"I sent you without purse, bag or sandals… now if you have a purse, take it, and also a bag; and if you don't have a sword, sell your cloak and buy one…. The disciples said, "See, Lord, here are two swords." "That is enough," he replied. (Luke 22:35-38)

These descriptions of the Last Supper are followed in the synoptic gospels by Jesus leading his disciples toward the Garden of Gethsemane, although once again not in the Gospel of John. There, Jesus commands his three core disciples to keep watch while he prays. While the disciples doze, Judas is able to approach with the Temple guards, who arrest Jesus and lead him to his fate.

Remembrances

In Early Christianity the tradition of agape feasts evolved into the ritual of Holy Communion, in which the story of the Last Supper plays a key role. Originally, these "love feasts" were apparently a full meal, with each participant bringing food, and with the meal eaten in a common room. The feast was held on Sundays, which became known as the "the Lord's Day," to recall the resurrection. At some point in the evolving tradition, the invocation of Jesus' words over bread and wine began to be invoked. At what point the agape feasts became commemorations of the Last Supper is a matter of much discussion.

The meals eventually evolved into more formal worship services and became codified as the Mass in Catholic Church and as the Divine Liturgy in the Orthodox Churches. At these liturgies, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians celebrate the sacrament of the Eucharist, a Greek word (eucharistia) which means "thanksgiving." The various denominations of Protestantism developed widely divergent theologies about the exact meaning the Eucharist and the role of the Last Supper in their traditions.

The historical Last Supper

As with many events in the life of Jesus, what actually happened historically at the Last Supper is not easy to discern. The synoptic gospels, supplemented with other details from the Gospel of John, paint a picture which has passed vividly into the collective memory of the Christian world. However, with the advent of biblical criticism in the nineteenth century, many of the details are now questioned.

Critics point out that the gospels were written at least a generation after the facts they describe. The synoptics appear to presume that Paul's revelation about the institution of the Eucharist was a real historical event and thus present it as such. Moreover, all of the gospels, again in accord with Paul's theology, presume that Jesus' crucifixion was God's original intent in sending him as the Messiah. Thus, Jesus is presented as knowing beforehand that he would soon die, that Judas was the one who would betray him, that Peter would deny him, and that his disciples would all abandon him.

Hints found in the New Testament, however, indicate that this may be a historical reconstruction based on later theological beliefs. For example, the fact that the Gospel of John remembers the Last Supper so differently from the synoptics shows that the communal memory of events was not clear. Different Christian communities were not in agreement over such details as what day of the week the meal was held on, whether it was as a Passover Seder or not, and whether Jesus instituted the Eucharist at this time or much earlier in his ministry.

Moreover, critics point out the disciples were greatly surprised and disillusioned by Jesus' crucifixion, which would not be the case if this had been a clear teaching of Jesus as he raised up the disciples to understand his mission in this way. Luke's story of the meeting on the road to Emmaus, for example, shows that the disciples as deeply shocked at Jesus' death since they expected him to fulfill the role of the Jewish Messiah by restoring the kingdom of Israel (Luke 24:19-20). Mark describes the disciples as all running away after Jesus arrest. John 21 describes the apostles as returning to the profession of fishing after Jesus' death. Luke 24:45-46 makes it clear that the disciples were not taught and did not believe that Jesus was supposed to die. The crucifixion thus seems to have caught Jesus' followers by surprise, throwing them into a deep crisis that was later resolved primarily by Paul (not present to Jesus' education of the disciples) who contrived a theology that the death of Jesus was foreordained by God. Jesus seeming announcement of his impending betrayal and death at the Last Supper has been confused with the Pauline innovation that this death was foreordained.

The conclusion of most critical scholars is thus that the description of the Last Supper is largely the product of church tradition centering on the Eucharist, evolving after the fact and later written back into the historical record of the gospels.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Raymond Edward. An Introduction to the New Testament. The Anchor Bible reference library. New York: Doubleday, 1997. ISBN 9780385247672

- Eichhorn, Albert, and Hugo Gressmann. The Lord's Supper in the New Testament. (History of Biblical studies, no. 1.) Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2007. ISBN 9781589832749

- Frederickson, Bruce G. Passover to Communion. Saint Louis: Concordia Pub. House, 2008. ISBN 9780758614711 (OCLC 228779938)

- Jeremias, Joachim. The Eucharistic Words of Jesus.. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977. ISBN 9780800613198

- Kodell, Jerome. The Eucharist in the New Testament. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1991. ISBN 9780814656631

- Koenig, John. The Feast of the World's Redemption: Eucharistic Origins and Christian Mission. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 2000. ISBN 9781563382741

- Wright, Ralph. Our Daily Bread: Glimpsing the Eucharist Through the Centuries. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2008. ISBN 9780809145256

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.