Difference between revisions of "Gaur" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Overview and description== | ==Overview and description== | ||

[[Image:Bos gaurus male münchen 2003.jpg|right|250px|thumb|Gaur bull with the typical high dorsal ridge]] | [[Image:Bos gaurus male münchen 2003.jpg|right|250px|thumb|Gaur bull with the typical high dorsal ridge]] | ||

| − | The gaur is recognized by the high convex ridge on the forehead between the horns, which bends forward, causing a deep hollow in the profile of the upper part of the head. The horns are found in both sexes, and grow from the sides of the head, curving upwards. They are regularly curved throughout their length, and are bent inward and slightly backward at their tips. The horns are flattened to a greater or less degree from front to back, more especially at their bases, where they present an elliptical cross-section; this characteristic being more strongly marked in the bulls than in the cows. Yellow at the base and turning black at the tips, the horns grow to a length of 80 centimeters (32 inches). A bulging gray-tan ridge connects the horns on the forehead. | + | The gaur is recognized by the high convex ridge on the forehead between the horns, which bends forward, causing a deep hollow in the profile of the upper part of the head. |

| + | |||

| + | The horns are found in both sexes, and grow from the sides of the head, curving upwards. They are regularly curved throughout their length, and are bent inward and slightly backward at their tips. The horns are flattened to a greater or less degree from front to back, more especially at their bases, where they present an elliptical cross-section; this characteristic being more strongly marked in the bulls than in the cows. Yellow at the base and turning black at the tips, the horns grow to a length of 80 centimeters (32 inches). A bulging gray-tan ridge connects the horns on the forehead. | ||

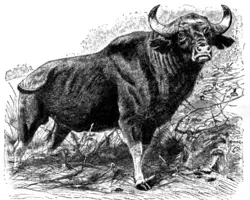

[[Image:GaurLyd2.png|thumb|left|250px]] | [[Image:GaurLyd2.png|thumb|left|250px]] | ||

The animals have a distinct ridge running from the shoulders to the middle of the back; the difference in height between the shoulders and rump may be as much as five inches in height. This ridge is caused by the great height of the spines of the vertebrae of the fore part of the trunk as compared with those of the loins. | The animals have a distinct ridge running from the shoulders to the middle of the back; the difference in height between the shoulders and rump may be as much as five inches in height. This ridge is caused by the great height of the spines of the vertebrae of the fore part of the trunk as compared with those of the loins. | ||

| − | The ears are very large and the tail only just reaches the hocks. There is a dewlap under the chin which extends between the front legs. There is a shoulder hump, especially pronounced in adult males. The hair is short, fine, and glossy, and the hoofs are narrow and pointed (Lydekker 1893). In old bulls the hair becomes very thin on the back (Lydekker 1893). | + | The ears are very large and the tail only just reaches the hocks. There is a dewlap under the chin which extends between the front legs. There is a shoulder hump, especially pronounced in adult males. The hair is short, fine, and glossy, and the hoofs are narrow and pointed (Lydekker 1893). In old bulls, the hair becomes very thin on the back (Lydekker 1893). |

Gaur are said to look like the front of a [[Wild Asian Water Buffalo|water buffalo]] with the back of a domestic [[cattle]]. Males have a highly muscular body, with a distinctive dorsal ridge and a large dewlap, forming a very powerful appearance. Females are substantially smaller, and their dorsal ridge and dewlaps are less developed. | Gaur are said to look like the front of a [[Wild Asian Water Buffalo|water buffalo]] with the back of a domestic [[cattle]]. Males have a highly muscular body, with a distinctive dorsal ridge and a large dewlap, forming a very powerful appearance. Females are substantially smaller, and their dorsal ridge and dewlaps are less developed. | ||

| − | Gaurs | + | Gaurs have a body length of about 2.5 to 3.6 meters (8.3-12 feet), a shoulder height of about 1.7 to 2.2 meters (5.6-7.2 feet), and a tail length of 0.7 to 1 meter (28-40 inches). On average, males stand about 1.8 meters to 1.9 meters at the shoulder, while females are about 20 centimeters less. Gaurs are the only wild bovids to exceed a shoulder height of 2 meters. |

| − | + | Gaurs are the heaviest and most powerful of all wild bovids. Males often reach 1000 to 1500 kilograms (2200-3300 pounds) and females 700 to 1000 kilograms (1540-2200 pounds). The three wild subspecies generally recognized vary in terms of weight. The Southeast Asian gaur is the largest, and the Malayan gaur is the smallest. The male Indian gaurs average 1300 kilograms, and large individuals may exceed 1700 kilograms, or 1.7 tons. On the other hand, a Malayan gaur usually weighs 1000 to 1300 kilograms. The largest of all gaur, the Southeast Asian gaur, weighs about 1500 kilograms (1.5 tons) for an average male. | |

In color, the adult male gaur is dark brown, approaching black in very old individuals; the upper part of the head, from above the eyes to the nape of the neck, is, however, ashy gray, or occasionally dirty white; the muzzle is pale colored, and the lower part of the legs pure white. The cows and young bulls are paler, and in some instances have a rufous tinge, which is most marked in individuals inhabiting dry and open districts. The color of the horns is some shade of pale green or yellow throughout the greater part of their length, but the tips are black (Lydekker 1893). | In color, the adult male gaur is dark brown, approaching black in very old individuals; the upper part of the head, from above the eyes to the nape of the neck, is, however, ashy gray, or occasionally dirty white; the muzzle is pale colored, and the lower part of the legs pure white. The cows and young bulls are paler, and in some instances have a rufous tinge, which is most marked in individuals inhabiting dry and open districts. The color of the horns is some shade of pale green or yellow throughout the greater part of their length, but the tips are black (Lydekker 1893). | ||

| − | |||

==Ecology and behavior== | ==Ecology and behavior== | ||

Revision as of 00:37, 24 December 2008

| Gaur | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A bull gaur diorama at the American Museum of Natural History

| ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Bos gaurus Smith, 1827 |

In zoology, gaur is the common name for a large, dark-coated, wild bovid, Bos gaurus, characterized by white or tan lower legs, large ears, strongly and regularly curved horns that curve inward and backward at the tip, and a a ridge and hollow on the forehead. The ridge on the back is very strongly marked, and there is no distinct dewlap on the throat and chest. The gaur is found in South Asia and Southeast Asia, with the biggest populations today found in India. The gaur (previously Bibos gauris) belongs to the same genus, Bos, as cattle (Bos taurus) and yaks (B. grunniens) and is the largest wild bovid (family Bovidae), being bigger than the Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) , water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), and bison (Bison sp.).

The gaur also is called seladang or in context with safari tourism Indian bison, although this is technically incorrect as it does not belong to the Bison genus. The gayal or mithun (Bos frontalis or B. gaurus frontalis) is often considered the domesticated form of the gaur.

Overview and description

The gaur is recognized by the high convex ridge on the forehead between the horns, which bends forward, causing a deep hollow in the profile of the upper part of the head.

The horns are found in both sexes, and grow from the sides of the head, curving upwards. They are regularly curved throughout their length, and are bent inward and slightly backward at their tips. The horns are flattened to a greater or less degree from front to back, more especially at their bases, where they present an elliptical cross-section; this characteristic being more strongly marked in the bulls than in the cows. Yellow at the base and turning black at the tips, the horns grow to a length of 80 centimeters (32 inches). A bulging gray-tan ridge connects the horns on the forehead.

The animals have a distinct ridge running from the shoulders to the middle of the back; the difference in height between the shoulders and rump may be as much as five inches in height. This ridge is caused by the great height of the spines of the vertebrae of the fore part of the trunk as compared with those of the loins.

The ears are very large and the tail only just reaches the hocks. There is a dewlap under the chin which extends between the front legs. There is a shoulder hump, especially pronounced in adult males. The hair is short, fine, and glossy, and the hoofs are narrow and pointed (Lydekker 1893). In old bulls, the hair becomes very thin on the back (Lydekker 1893).

Gaur are said to look like the front of a water buffalo with the back of a domestic cattle. Males have a highly muscular body, with a distinctive dorsal ridge and a large dewlap, forming a very powerful appearance. Females are substantially smaller, and their dorsal ridge and dewlaps are less developed.

Gaurs have a body length of about 2.5 to 3.6 meters (8.3-12 feet), a shoulder height of about 1.7 to 2.2 meters (5.6-7.2 feet), and a tail length of 0.7 to 1 meter (28-40 inches). On average, males stand about 1.8 meters to 1.9 meters at the shoulder, while females are about 20 centimeters less. Gaurs are the only wild bovids to exceed a shoulder height of 2 meters.

Gaurs are the heaviest and most powerful of all wild bovids. Males often reach 1000 to 1500 kilograms (2200-3300 pounds) and females 700 to 1000 kilograms (1540-2200 pounds). The three wild subspecies generally recognized vary in terms of weight. The Southeast Asian gaur is the largest, and the Malayan gaur is the smallest. The male Indian gaurs average 1300 kilograms, and large individuals may exceed 1700 kilograms, or 1.7 tons. On the other hand, a Malayan gaur usually weighs 1000 to 1300 kilograms. The largest of all gaur, the Southeast Asian gaur, weighs about 1500 kilograms (1.5 tons) for an average male.

In color, the adult male gaur is dark brown, approaching black in very old individuals; the upper part of the head, from above the eyes to the nape of the neck, is, however, ashy gray, or occasionally dirty white; the muzzle is pale colored, and the lower part of the legs pure white. The cows and young bulls are paler, and in some instances have a rufous tinge, which is most marked in individuals inhabiting dry and open districts. The color of the horns is some shade of pale green or yellow throughout the greater part of their length, but the tips are black (Lydekker 1893).

Ecology and behavior

In the wild, gaurs live in small herds of up to 40 individuals and graze on grasses, shoots, and fruits. Where gaurs have not been disturbed, they are basically diurnal, being most active in the morning and late afternoon and resting during the hottest time of the day. But where populations have been disturbed by human populations, gaurs have become largely nocturnal, rarely seen in the open by mid-morning.

During the dry season, herds congregate and remain in small areas, dispersing into the hills with the arrival of the monsoon. While gaurs depend on water for drinking, they do not seem to bathe or wallow.

Due to their formidable size and power, the gaur has few natural enemies. Crocodiles, leopards, and dhole packs occasionally attack unguarded calves or unhealthy animals, but only the tiger has been reported to kill a full-grown adult. One of the largest bull gaur seen by George Schaller during the year 1964 in Kanha national park was killed by a tiger (Schaller 1967). On the other hand, there are several cases of tigers being killed by gaur. In one instance, a tiger was repeatedly gored and trampled to death by a gaur during a prolonged battle (Sunquist and Sunquist 2002). In another case, a large male tiger carcass was found beside a small broken tree in Nagarahole national park, being fatally struck against the tree by a large bull gaur a few days earlier (Karanth and Nichols 2002). When confronted by a tiger, the adult members of a gaur herd often form a circle surrounding the vulnerable young and calves, shielding them from the big cat. A herd of gaur in Malaysia encircled a calf killed by a tiger and prevented it from approaching the carcass (Schaller 1967), while in Nagarahole, upon sensing a stalking tiger, a herd of gaur walked as a menacing phalanx towards it, forcing the tiger to retreat and abandon the hunt (Karanth 2001). Gaurs are not as aggressive toward humans as wild Asian water buffaloes (Perry 1965).

A family group consists of small mixed herds of 2-40 individuals. Gaur herds are led by an old adult female (the matriarch). Adult males may be solitary. During the peak of the breeding season, unattached males wander widely in search of receptive females. No serious fighting between males has been recorded, with size being the major factor in determining dominance. Males make a mating call of clear, resonant tones which may carry for more than 1.6 kilometres. Gaurs have also been known to make a whistling snort as an alarm call, and a low, cow-like moo.

The average population density is about 0.6 animals per square kilometre, with herds having home ranges of around 80 square kilometres.

The gaur belongs to the wild oxen family, which includes wild water buffaloes. In some regions in India where human disturbance is minor, the gaur is very timid and shy, and often shuns humans. When alarmed, gaurs crash into the jungle at a surprising speed. However, in South-east Asia and south India, where they are used to the presence of humans, gaurs are said by locals to be very bold and aggressive. They are frequently known to go down fields and graze alongside domestic cattle, sometimes killing them in fights. Gaur bulls may charge unprovoked, especially during summer time when the heat and parasitic insects make them more short-tempered than usual. To warn other members of its herd of approaching danger, the gaur lets out a high whistle for help.

Life history and reproduction

- Gestation period: 275 days.

- Young per birth: 1, rarely 2

- Weaning: 7-12 months.

- Sexual maturity: In the 2nd and 3rd year.

- Life span: About 30 years.

- Breeding takes place throughout the year, though there is a peak between December and June.

Subspecies

- Bos gaurus laosiensis (Heude, 1901; Myanmar to China), the South-east Asian gaur, sometimes also known as Bos gaurus readei (Lydekker, 1903).[1] This is the most endangered gaur subspecies. Nowadays, it is found mainly in Indochina and Thailand. The population in Myanmar has been wiped out almost entirely. Southeast Asian gaurs are now found mainly in small populations in scattered forests in the region. Many of these populations are too small to be genetically viable; moreover, they are isolated from each other due to habitat fragmentation. Together with illegal poaching, this will likely put an end to this subspecies in the not so distant future. Currently the last strongholds of these giants, which contain viable populations for long-term survival are Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve in southern Yunnan, China, Cat Tien National Park in VietNam, and Virachey national park in Cambodia. These forests, however, are under heavy pressure, suffering from the same poaching and illegal logging epidemic common in all other forests in South-east Asia.

- Bos gaurus gaurus[2] (India, Bangladesh, Nepal) also called "Indian bison". This is the most populous subspecies, containing more than 90 percent of the entire gaur population in the world. In 2006, a rare Manjampatti White Bison[3] was seen and photographed in Manjampatti Valley by Forest Department staff[4] and was also seen on the nearby mountain downs above Kukkal in Tamil Nadu.

- Bos gaurus hubbacki (Thailand, Malaysia). Found in southern Thailand and Malaysia peninsular, is the smallest subspecies of gaur.

- Bos gaurus frontalis[5], domestic gaur, probably a gaur-cattle hybrid breed

The wild group and the domesticated group are sometimes considered separate species, with the wild gaur called Bibos gauris or Bos gaurus, and the domesticated gayal or mithun (mithan) called Bos frontalis Lambert, 1804.

When wild Bos gaurus and the domestic Bos frontalis are considered to belong to the same species the older name Bos frontalis is used, according to the rules of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). However, in 2003, the ICZN "conserved the usage of 17 specific names based on wild species, which are pre-dated by or contemporary with those based on domestic forms", confirming Bos gaurus for the Gaur.[6]

Previously thought to be closer to bison, genetic analysis has found that they are closer to cattle with which they can produce fertile hybrids. They are thought to be most closely related to banteng and said to produce fertile hybrids.

Distribution

Tropical Asian woodlands interspread with clearings in the following countries: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India,Pakistan, Laos, Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia), Myanmar, Borneo, Nepal, Thailand, Viet Nam (IUCN, 2002).

Cloning

At 7:30 PM on Monday, 8 January 2001, the first successful birth of a cloned animal that is a member of an endangered species occurred, a gaur named Noah at Trans Ova Genetics in Sioux Center Iowa. He was carried and brought successfully by a surrogate mother from another, more common, species, in this case a domestic cow named Bessie. The biotechnology company Advanced Cell Technology was the first to succeed. While healthy at birth, Noah died within 48 hours of a common dysentery, likely unrelated to cloning. [7]

Miscellaneous

To the Adi people, the possession of gaur is the traditional measure of a family's wealth. In the Adi language, gaur are called "Tadok" and often referred to as "Mithun". Gaur are not milked or put to work but given supplementary care while grazing in the woods, until they are slaughtered.

External links

- Distribution and conservation of the Gaur Bos gaurus in the Indian Subcontinent

- Sankar, K.; Qureshi, Q : Ecology of gaur (Bos Gaurus) in Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, Table of Contents & Summary, pp. XIX

- Gaur bos gaurus Lambert from wildcattleconservation.org

- Gaur being killed and poisoned

- ARKive - images and movies of the gaur (Bos frontalis)

- Gaur fact sheet

- Images of Indian gaur

- Gaur in Mudumalai

- Thirteen Years Among the Wild Beasts of India: Their Haunts and Habits from Personal Observation

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

.[9]

Lydekker, Richard. 1893. The royal natural history. London: F. Warne.

[11].

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Former names: Bos annamiticus, Bos brachyrhinus, Bos diardii, Bos fuscicornis, Bos hubbacki, Bos leptoceros, Bos mekongensis, Bos platyceros, Bos readei, Bos sylvanus refered to the subspecies Bos frontalis laosiensis.

- ↑ Also known as Bison gaurus (Hamilton Smith, 1827), Bos gour (Hardwicke, 1827), Bibos cavifrons (Hodgson, 1837), , Bos guavera (Kerr, 1792), Bibos subhemachalanus (Hodgson, 1837), Bisonius subhaemachalensis (Hodgson), Bos Hardwickii (J. Brook, 1825), Bos aculeatus (Cuvier), Bos asseel (Horsefield, 1851)…

- ↑ The Indian Forester, Published by R. P. Sharma, Business Manager, Indian Forester. (1974) Item notes: v.100 1974 no.1-6, Original from the University of Michigan, page 186, Digitized Nov 1, 2007

- ↑ Maloney Clarence ed, Contributions by R G Sekar, Forester; T K Subramaniam, Forest Guard; B Nagarajan, Forest Watcher; V Ganesan, Forest Watcher; S Rajan, Headman of Thalinji village; Gopal, Headman of Manjampatti village; Appunan, a Muthuvan (2008-2-2), KodaiTalkease Trip Report], in text:, "Manjampatti Valley in the Palani Hills of South India: Its People and Environment", KodaiTalkEase 2008 (#14189): 1–12, Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, India, 2008-2-8

- ↑ Also known as asseel gayal, asseel gaydl, gau, gavi, Bos frontalis (Lambert, 1804), Bos gavaeus (Colebrook, 1805), Bos bubalis, Bos sylhetanus (F. Cuvier, 1824)…

- ↑ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 2003. Opinion 2027 (Case 3010). Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are pre-dated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved. Bull.Zool.Nomencl., 60:81-84.

- ↑ Advanced Cell Technology. 2001. Advanced Cell Technology, Inc. announced that the first cloned endangered animal was born at 7:30 PM on Monday, January 8, 2001. Press Release of 12 January 2001. Downloaded at 18 September 2006 from [1].

- ↑ Karanth U.& Nichols J.: Monitoring Tigers and Their Prey . Center for wildlife studies, 2002.

- ↑ * Karanth U.: Tigers 2001. Colin Baxter Photography, 2001

- ↑ Perry, Richard (1965). The World of the Tiger, 260. ASIN: B0007DU2IU.

- ↑ Schaller, G: The Deer and the Tiger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1967

- ↑ * Schaller, G: The Deer and the Tiger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1967

- ↑ Sunquist, Mel and Fiona Sunquist. 2002. Wild Cats of the World. University Of Chicago Press, Chicago