Difference between revisions of "Eleanor of Aquitaine" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Conflict) |

|||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

== Crusade == | == Crusade == | ||

[[Image:Bernhard von Clairvaux (Initiale-B).jpg|thumb|Bernard of Clairvaux.]] | [[Image:Bernhard von Clairvaux (Initiale-B).jpg|thumb|Bernard of Clairvaux.]] | ||

| − | Eleanor and Louis took up the cross during a sermon preached by [[Bernard of Clairvaux]]. She was followed by some of her royal ladies in waiting as well as 300 non-noble vassals. She insisted on taking part in the [[Crusades]] as the feudal leader of the soldiers from her duchy. The story that she and her ladies dressed as [[Amazons]] is disputed by | + | Eleanor and Louis took up the cross during a sermon preached by [[Bernard of Clairvaux]]. She was followed by some of her royal ladies in waiting as well as 300 non-noble vassals. She insisted on taking part in the [[Crusades]] as the feudal leader of the soldiers from her duchy. <ref>The story that she and her ladies dressed as [[Amazons]] is disputed by historians.</ref> Her testimonial launch of the [[Second Crusade]] from Vézelay, the supposed location of [[Mary Magdalene]]´s burial, dramatically emphasized the role of women in the campaign. She inspired more vassals to join the Crusade than her husband did. |

| − | Many women went on crusade seeking martyrdom to receive instant redemption to be able to join the saints in Heaven, others went seeking penance for their sins. Eleanor was religious throughout her life but | + | Many women went on crusade seeking martyrdom to receive instant redemption to be able to join the saints in Heaven, others went seeking penance for their sins. Eleanor was religious throughout her life but her motivation in taking up the cross is not known. <ref>Some suggest that it could have been in penance for the deaths at Vitry, others that it could have been to seek adventure and see new sights in a righteous cause.</ref> |

| − | The Crusade itself achieved little due to Louis' | + | The Crusade itself achieved little, due both to Louis' ineffective leadership and the hindering of the [[Byzantine Emperor]] [[Manuel I Comnenus]], who feared that the French army would jeopardize the tenuous safety of his empire. However, during their three-week stay with the Emperor at [[Constantinople]], Louis was fêted and Eleanor was much admired. She was compared with [[Penthesilea]], mythical queen of the [[Amazons]], by the Greek historian [[Nicetas Choniates]]. He added that she gained the epithet ''chrysopous'' (golden-foot) from the cloth of gold that decorated and fringed her robe. |

| − | From the moment the Crusaders entered Asia Minor, the Crusade went badly. The King and Queen, wrongly informed of a German victory, boldly marched on only to discover the remnants of the German army, including a dazed and sick Emperor Conrad, who brought news | + | From the moment the Crusaders entered Asia Minor, the Crusade went badly. The King and Queen, wrongly informed of a German victory, boldly marched on only to discover the remnants of the German army, including a dazed and sick Emperor Conrad, who brought news disaster. The French, with what remained of the Germans, then began to march in increasingly disorganized fashion, toward Antioch. Their spirits were buoyed on Christmas Eve--when camped near Ephesus and were ambushed by a Turkish detachment—but proceeded proceeded to slaughter this detachment and appropriate their camp instead. |

| − | As they ascended the Phrygian mountains, on the way to Eleanor's uncle Raymond in Antioch, the army and the King and Queen were horrified by the unburied corpses of the previously slaughtered German army. Eleanor's Aquitainian vassal, [[Geoffrey de Rancon]] led the march to the crossing of Mount Cadmos. Louis chose to take charge of the rear of the column, where the unarmed pilgrims and the baggage trains marched. Geoffrey unencumbered by baggage, chose to go further than planned which left the slower train open to attack by Turks, who had been following behind. | + | As they ascended the Phrygian mountains, on the way to Eleanor's uncle Raymond in Antioch, the army and the King and Queen were horrified by the unburied corpses of the previously slaughtered German army. Eleanor's Aquitainian vassal, [[Geoffrey de Rancon]] led the march to the crossing of Mount Cadmos. Louis chose to take charge of the rear of the column, where the unarmed pilgrims and the baggage trains marched. Geoffrey, unencumbered by baggage, chose to go further than planned, which left the slower train open to attack by Turks, who had been following behind. |

| − | The Turks | + | The Turks had seized the summit of the mountain, and the French (both soldiers and pilgrims) having been taken by surprise, had little hope of escape. Those who tried were caught and killed, and many men, horses and baggage were cast into the canyon below the ridge. William of Tyre placed the blame for this disaster firmly on the baggage--which was considered to have belonged largely to the women traveling with Eleanor. |

| − | The | + | The official scapegoat for the disaster was Geoffrey de Rancon, who had made the bad decision to continue beyond the planned stop, and it was suggested that he be hanged (a suggestion which the King ignored). Since he was Eleanor's vassal, this did nothing for her popularity in [[Christendom]]. Eleanor's reputation was further sullied by her supposed affair with her uncle [[Raymond of Antioch|Raymond of Poitiers]], [[Prince of Antioch]] when she decide to stay with him, probably angry with Louis. Eleanor was enraptured with the glamor of Antioch and with the reconnection to her uncle, who must have seemed much more interesting and worldly than her husband, "the monk."<ref>Wheeler (year)</ref> Louis, in retaliation, had her dragged out of the castle and put on board a separate ship to go home. |

| − | The | + | ==Maritime innovations== |

| + | The trip was not a total loss, however. While in the eastern Mediterranean, Eleanor learned about the maritime conventions developing there, which were the beginnings of what would become [[admiralty law]]. She introduced those conventions in her own lands, both on the island of [[Oleron]] in 1160 and later in England as well. She was also instrumental in developing trade agreements with Constantinople and ports of trade in the Holy Lands. | ||

| − | Eleanor was | + | == Annulment of first marriage == |

| + | [[Image:Dräkt, Riddare och drottning, Nordisk familjebok.png|thumb|right|130px|Medieval clothing]] | ||

| + | Even before the Crusade, Eleanor and Louis were becoming estranged. The city of Antioch had been annexed by Bohemond of Hauteville in the First Crusade, and it was now ruled by Eleanor's flamboyant uncle, [[Raymond of Antioch]], who had gained the principality by marrying its reigning Princess, [[Constance of Antioch]]. Clearly, Eleanor supported his desire to re-capture the nearby [[County of Edessa]], which was a major cause of the Crusade. In addition, having been close to him in their youth, she now showed excessive affection towards her uncle. While many historians today dismiss this as familial affection, amny at the time firmly believed the two to be involved in an incestuous and adulterous affair. Louis was directed by the Church to visit [[Jerusalem]] instead. When Eleanor declared her intention to stand with Raymond and the Aquitaine forces, Louis had her brought out by force. His long march to Jerusalem and back north debilitated his army, but her imprisonment disheartened her knights, and the divided Crusade armies could not overcome the [[Muslim]] forces. For reasons unknown, likely the Germans' insistence on conquest, the Crusade leaders targeted [[Damascus]], an ally until the attack. Failing in this attempt, they retired to Jerusalem, and then home. | ||

| − | + | Home, however, was not easily reached. The royal couple, on separate ships due to their disagreements, were first attacked in May by Byzantine ships attempting to capture both (in order to take them to Byzantium, according to the orders of the Emperor). Although they escaped this predicament unharmed, stormy weather served to drive Eleanor's ship far to the south (to the Barbary Coast). Neither was heard of for over two months, at which point, in mid-July, Eleanor's ship finally reached Palermo in Sicily, where she discovered that both she and her husband had been given up for dead. The King still lost, she was given shelter and food by servants of King [[Roger of Sicily]], until the Louis eventually reached Calabria, and she set out to meet him there. Later, at King Roger's court in Potenza, she learned of the death of her Uncle Raymond. This appears to have forced a change of plans, for instead of returning to France, they instead sought out the [[Pope Eugenius III]] in Tusculum, where he had been driven five months before by a Roman revolt. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The Pope did not, as Eleanor had hoped, grant a divorce; instead, he attempted to reconcile Eleanor and Louis, confirming the legality of their marriage, and proclaiming that no word could be spoken against it. Eventually, he maneuvered events so that Eleanor had no choice but to sleep with Louis in a bed specially prepared by the Pope. Eleanor thus conceived their second daughter, but the disappointment over the lack of a son only further endangered the marriage. Worried about being left with no male heir, facing substantial opposition to Eleanor from many of his Barons, and recognizing his wife's own desire for divorce, Louis had no choice but to bow to the inevitable. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | Louis had lost the champion of his marriage in Abbot Suger, who had died in 1151. He and Eleanor met on March 11, 1152, at the royal castle of Beaugency to dissolve the marriage. Archbishop [[Hugh Sens]], Primate of France, presided, and the archbishops of Bordeaux and Rouen were also present. Archbishop Sampson of [[Rheims]] acted for Eleanor. On March 21 the four archbishops, with the approval of Pope Eugenius, granted an annulment due to [[consanguinity]] within the fourth degree. <ref>Consanguinity is defined as a relationship by blood or by a common ancestor. Eleanor and Louis were third cousins, once removed and shared common ancestry with Robert II of France.</ref> Their two daughters were declared legitimate, however, and custody of them awarded to Louis. Archbishop Sampson received assurances from Louis that Eleanor's lands would be restored to her. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == Marriage to Henry II of England == | + | ==Marriage to Henry II of England== |

[[Image:Henry II of England.jpg|thumb|right|Henry II of England]] | [[Image:Henry II of England.jpg|thumb|right|Henry II of England]] | ||

| + | |||

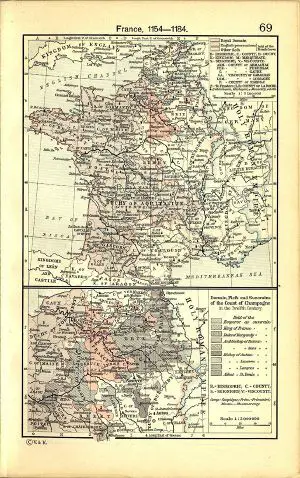

[[Image:France 12thC.jpg|thumb|right|The marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry of Anjou and Henry's subsequent succession to the throne of England created an empire.]] | [[Image:France 12thC.jpg|thumb|right|The marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry of Anjou and Henry's subsequent succession to the throne of England created an empire.]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | Two lords - Theobald of Blois, | + | Two lords--Theobald of Blois, ang Geoffrey of Anjou (brother of [[Henry II of England|Henry, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy]])--tried to kidnap Eleanor on her way to Poitiers in order to marry her and claim her lands, but she evaded them. As soon as she arrived in Poitiers, Eleanor sent envoys to Henry, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy, asking him to come at once and marry her. On [[Whit Sunday]], May 18, 1152, six weeks after her annulment, Eleanor married Henry 'without the pomp and ceremony that befitted their rank'.<ref>''Chronique de Touraine''</ref> She was nearly 11 years older than he, and related to him more closely than she had been to Louis. One of Eleanor's rumored lovers had been Henry's own father, [[Geoffrey of Anjou]], who had advised his son to avoid any involvement with her. But by uniting Eleanor's lands and Henry's, his dominion became the greatest in Europe, much larger than that of France. |

In the nearly two months she lived in Aquitaine before Henry arrived to marry her, she could rule in her own name, adjudicate in her own name and did so with the full support of her people. She was the lord of Aquitaine, due to the brilliant strategy of her father in insisting that she alone could claim the duchy. This right of rule for women was diminishing until it would rise again in England with Queen Elisabeth I, daughter of Henry VIII. | In the nearly two months she lived in Aquitaine before Henry arrived to marry her, she could rule in her own name, adjudicate in her own name and did so with the full support of her people. She was the lord of Aquitaine, due to the brilliant strategy of her father in insisting that she alone could claim the duchy. This right of rule for women was diminishing until it would rise again in England with Queen Elisabeth I, daughter of Henry VIII. | ||

| − | The popularity of the royal couple was linked to the ancient prophecies of Merlin, popular in Europe in the twelfth century, which were often thought to refer to the family of Henry II: "The eagle of the broken covenant, shall rejoice in her third nesting." Eleanor was thought to be the eagle, the broken covenant was the dissolution of her marriage to Louis, and the third nesting was thought to be the birth of her third son, Richard who would later be king.<ref>''Eleanor of Aquitaine'', Alison Weir</ref> | + | The popularity of the royal couple was linked to the ancient prophecies of [[Merlin]], popular in Europe in the twelfth century, which were often thought to refer to the family of Henry II: "The eagle of the broken covenant, shall rejoice in her third nesting." Eleanor was thought to be the eagle, the broken covenant was the dissolution of her marriage to Louis, and the third nesting was thought to be the birth of her third son, Richard who would later be king.<ref>''Eleanor of Aquitaine'', Alison Weir</ref> |

| − | Over the next | + | Over the next 13 years, she bore Henry five sons and three daughters: [[William, Count of Poitiers|William]], [[Henry the Young King|Henry]], [[Richard I of England|Richard]], [[Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany|Geoffrey]], [[John I of England|John]], [[Matilda of England|Matilda]], [[Leonora of Aquitaine|Eleanor]], and [[Joan of England, Queen consort of Sicily|Joanna]]. <ref>John Speed, in his 1611 work, ''History of Great Britain'', mentions the possibility that Eleanor had a son named Philip, who died young. His sources no longer exist and he alone mentions this birth. Weir, Alison, ''Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Life'', pages 154-155, Ballantine Books, 1999</ref> |

| − | Henry was by no means faithful to his wife | + | Henry had a reputation for philandering and was by no means faithful to his wife. Their son, William, and Henry's illegitimate son, Geoffrey, were born just months apart. Henry fathered other illegitimate children throughout the marriage. Eleanor appears to have taken an ambivalent attitude toward these affairs: for example, Geoffrey of York, an illegitimate son of Henry and a prostitute named Ykenai, was acknowledged by Henry as his child and raised at Westminster in the care of the Queen. |

| − | The period between Henry's accession and the birth of Eleanor's youngest son was turbulent | + | is Geof of York the same as the Geof born months apart from william? |

| + | this is not clear. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The period between Henry's accession and the birth of Eleanor's youngest son was turbulent. Aquitaine, as was the norm, defied the authority of Henry as Eleanor's husband. Attempts to claim Toulouse, the rightful inheritance of Eleanor's grandmother and father, were made, ending in failure; the news of Louis of France's widowhood and remarriage was followed by the marriage of Henry's son (young Henry) to Louis' daughter Marguerite; and, most climatically, the feud between the King and Thomas Becket, his Chancellor, and later his Archbishop of Canterbury. Little is known of Eleanor's involvement in these events, however. By late 1166, and the birth of her final child, however, Henry's notorious affair with [[Rosamund Clifford]] had become known, and her marriage to Henry appears to have become terminally strained. | ||

| + | |||

| + | the above Par. is too thick | ||

[[Image:Eleanor-and-Rosamond.jpg|thumb|Eleanor confronts Rosamund over her affair with Henry.]] | [[Image:Eleanor-and-Rosamond.jpg|thumb|Eleanor confronts Rosamund over her affair with Henry.]] | ||

| − | 1167 saw the marriage of Eleanor's third daughter, Matilda, to Henry the Lion of Saxony; Eleanor remained in England with her daughter for the year prior to Matilda's departure to Normandy in September. Afterwards, Eleanor proceeded to gather together her movable possessions in England and transport them on several ships in December to Argentan. At the royal court, celebrated there that Christmas, she appears to have agreed to a separation from Henry. Certainly, she left for her own city of Poitiers immediately after Christmas. Henry did not stop her; on the contrary, he and his army personally escorted her there, before attacking a castle belonging to the rebellious Lusignan family. Henry then went about his own business outside Aquitaine, leaving Earl Patrick (his regional military commander) as her protective custodian. When Patrick was killed in a skirmish, Eleanor (who proceeded to ransom his captured nephew, the young [[William Marshal]]), was left in control of her inheritance. Eleanor assumed control of the duchy of Aquitaine with Henry's support, after the death of his mother, Mathilda, in 1167. Perhaps, Henry had had enough of strong willed women and wished to be free. | + | The year 1167 saw the marriage of Eleanor's third daughter, Matilda, to Henry the Lion of Saxony; Eleanor remained in England with her daughter for the year prior to Matilda's departure to Normandy in September. Afterwards, Eleanor proceeded to gather together her movable possessions in England and transport them on several ships in December to Argentan. At the royal court, celebrated there that Christmas, she appears to have agreed to a separation from Henry. Certainly, she left for her own city of Poitiers immediately after Christmas. Henry did not stop her; on the contrary, he and his army personally escorted her there, before attacking a castle belonging to the rebellious Lusignan family. Henry then went about his own business outside Aquitaine, leaving Earl Patrick (his regional military commander) as her protective custodian. When Patrick was killed in a skirmish, Eleanor (who proceeded to ransom his captured nephew, the young [[William Marshal]]), was left in control of her inheritance. Eleanor assumed control of the duchy of Aquitaine with Henry's support, after the death of his mother, Mathilda, in 1167. Perhaps, Henry had had enough of strong willed women and wished to be free. |

| + | |||

At a small cathedral still stands the stained glass commemorating Eleanor and Henry with a family tree growing from their prayers. Away from Henry, Eleanor was able to encourage the cult of [[courtly love]] at her court. Apparently, however, both King and church expunged the records of the actions and judgments taken under her authority. A small fragment of her codes and practices was written by [[Andreas Capellanus]]. | At a small cathedral still stands the stained glass commemorating Eleanor and Henry with a family tree growing from their prayers. Away from Henry, Eleanor was able to encourage the cult of [[courtly love]] at her court. Apparently, however, both King and church expunged the records of the actions and judgments taken under her authority. A small fragment of her codes and practices was written by [[Andreas Capellanus]]. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

Henry concentrated on controlling his increasingly-large empire, badgering Eleanor's subjects in attempts to control her [[patrimony]] of Aquitaine and her court at [[Poitiers]]. Straining all bounds of civility, Henry caused the murder of Archbishop [[Thomas Becket]] at the altar of the church in 1170 (though there is considerable debate as to whether it was truly Henry's intent to be permanently rid of his archbishop). This aroused Eleanor's horror and contempt, along with most of Europe's. | Henry concentrated on controlling his increasingly-large empire, badgering Eleanor's subjects in attempts to control her [[patrimony]] of Aquitaine and her court at [[Poitiers]]. Straining all bounds of civility, Henry caused the murder of Archbishop [[Thomas Becket]] at the altar of the church in 1170 (though there is considerable debate as to whether it was truly Henry's intent to be permanently rid of his archbishop). This aroused Eleanor's horror and contempt, along with most of Europe's. | ||

Revision as of 00:43, 5 June 2007

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Duchess of Aquitaine and Gascony and Countess of Poitou (c. 1124 –April 1 1204) was one of the most powerful women in Europe during the High Middle Ages. She was Queen consort of both France and England in turn and the mother of both English Kings Richard I and John. She was one of the first women to take up the cross and go on crusade. She inspired and led her vassals to go with King Louis VII, her husband, on the

Early life

Ealeanor was raised in the court of her flamboyant, troubadour grandfather, William IX, who had been excommunicated due to his "kidnapping" of his lover, Dangereuse, from her husband, the Viscount of Châtellerault and living openly with her while William himself was still married to Philippa, mother of Eleanor's father. The court of William IX was filled with song, the culture of Courtly Love and abandance, as Aquitaine was the richest duchy in the south of France. William IX was very popular with his people despite his free-thinking lifestyle. In Aquitaine women were allowed a voice and even accepted as rulers during the times when Eleanor lived in the region.

The oldest of three children, Eleanor's father was William X, Duke of Aquitaine, and her mother was Aenor de Châtellerault, the daughter of Aimeric I, Vicomte of Châtellerault. Eleanor was named after her mother and called Aliénor, which means the other Aenor.

Inheritance and first marriage

In 1137, Duke William X left Eleanor and her sister Petronilla in the charge of the archbishop of Bordeaux, one of the Duke's few loyal vassals, on his way to the Shrine of Saint James of Compostela in North-western Spain for a pilgrimage of penance. However, on the April 9 (Good Friday), 1137 he was stricken with sickness, probably food poisoning and died that evening, having bequeathed the Aquitaine to Eleanor after receiving a premonition of his own death.

About the age of 13, Eleanor thus became the Duchess of Aquitaine, and the most eligible heiress in Europe. In those days kidnapping an heiress was seen as a viable option for attaining a title and lands. To prevent this, William had dictated a will appointing King Louis VI, nicknamed "the Fat", her guardian. His will indicated that Eleanor would retain the lands in her name even after she married, and that inheritance of these lands would follow Eleanor's heirs. He further requested that Louis find a suitable husband for her. Until a husband was found, the King had the right to use Eleanor's lands. Eleanor's father also ordered that his death be kept a secret until Louis was informed.

Louis the Fat, although old and gravely ill, remained clear-minded. Rather than act as guardian to the Duchess, he decided to immediately marry her to his own heir, and thus bring Aquitaine under the French crown. Within hours, Louis had arranged for his son, the future Louis VII, to be married to Eleanor, with the powerful Abbot Suger in charge of the wedding arrangements.

Louis VII arrived in Bordeaux on July 11, with an escort of 500 knights, and the next day, accompanied by the Archbishop of Bordeaux, the couple was married in the Cathedral of Saint-André. It was a magnificent ceremony with almost a thousand guests. She gave Louis a wedding present that is still in existence, a rock crystal vase, currently on display at the Louvre.However, there was a problem for Louis VII: Eleanor's land would remain independent of France. Her oldest son would be both King of France and Duke of Aquitaine. Thus, her holdings would not be merged with France until the next generation.

Something of a free spirit, Eleanor was not popular with the staid northerners. Her conduct was repeatedly criticized by Church elders, particularly Bernard of Clairvaux and Abbot Suger, as indecorous. The King, however, was madly in love with his beautiful and worldly young bride, and reportedly granted her every whim, even though her behavior baffled and vexed him to no end. Much money went into beautifying the austere Cité Palace in Paris for Eleanor's sake.

Conflict

Eleanor also received criticism in Louis' own court, especially for her outspokenness and dress, and was sometimes blamed for actions of her husband. For example, in 1147 Louis bolted the gates of Bourges against the Pope's new bishop, because he wished his own chancellor to hold that post. The Pope reportedly blamed Eleanor's for this. Outraged, Louis swore that the Pope's candidate should never enter Bourges. This brought the interdict upon the king's lands.

the 1147 story, above seems like it should come later?

Louis also became involved in a war with Count Theobald of Champagne, who had sided with the Pope, when Louis permitted Raoul I of Vermandois, to marry Eleanor's sister Petronilla after repudiating his wife (Theobald's niece), Lenora. Eleanor had urged Louis to support her sister's marriage to Raoul. The war lasted two years, and ended with the occupation of Champagne by the royal army. Louis was personally involved a attack on the town of Vitry. The town was burned, and more than 1,000 people, who had sought refuge in the local church, died in the flames.

In June of 1144, the King and Queen visited the newly built cathedral at Saint-Denis where the outspoken Eleanor met with Bernard of Clairvaux, demanding that he have the excommunication of Petronilla and Raoul lifted through his influence on the Pope. Dismayed at her attitude, Bernard scolded her for her lack of penitence and her interference in matters of state. In response, Eleanor broke down, claiming to be embittered because of her lack of children. Bernard then became more kindly towards her: "My child, seek those things which make for peace. Cease to stir up the King against the Church, and urge upon him a better course of action. If you will promise to do this, I in return, promise to entreat the merciful Lord to grant you offspring."

In a matter of weeks, peace had returned to France: Theobald's provinces had been returned, and the Pope's choice, Pierre de la Chatre, was installed as Archbishop of Bourges. And in 1145, Eleanor gave birth to a daughter, Marie.

Louis, however still burned with guilt over the massacre at Vitry-le-Brûlé, and desired to make a Pilgrimage to the Holy Land in order to atone for his sins. Fortuitously for him, in the Autumn of 1145, Pope Eugenius requested Louis to lead a Crusade to the Middle East to rescue the Frankish Kingdoms and Jerusalem from disaster. Accordingly, Louis declared on Christmas Day 1145 at Bourges his intention of going on a crusade. Eleanor, ever a pioneer, also determined to take up the cross and go on crusade.

Crusade

Eleanor and Louis took up the cross during a sermon preached by Bernard of Clairvaux. She was followed by some of her royal ladies in waiting as well as 300 non-noble vassals. She insisted on taking part in the Crusades as the feudal leader of the soldiers from her duchy. [1] Her testimonial launch of the Second Crusade from Vézelay, the supposed location of Mary Magdalene´s burial, dramatically emphasized the role of women in the campaign. She inspired more vassals to join the Crusade than her husband did.

Many women went on crusade seeking martyrdom to receive instant redemption to be able to join the saints in Heaven, others went seeking penance for their sins. Eleanor was religious throughout her life but her motivation in taking up the cross is not known. [2]

The Crusade itself achieved little, due both to Louis' ineffective leadership and the hindering of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus, who feared that the French army would jeopardize the tenuous safety of his empire. However, during their three-week stay with the Emperor at Constantinople, Louis was fêted and Eleanor was much admired. She was compared with Penthesilea, mythical queen of the Amazons, by the Greek historian Nicetas Choniates. He added that she gained the epithet chrysopous (golden-foot) from the cloth of gold that decorated and fringed her robe.

From the moment the Crusaders entered Asia Minor, the Crusade went badly. The King and Queen, wrongly informed of a German victory, boldly marched on only to discover the remnants of the German army, including a dazed and sick Emperor Conrad, who brought news disaster. The French, with what remained of the Germans, then began to march in increasingly disorganized fashion, toward Antioch. Their spirits were buoyed on Christmas Eve—when camped near Ephesus and were ambushed by a Turkish detachment—but proceeded proceeded to slaughter this detachment and appropriate their camp instead.

As they ascended the Phrygian mountains, on the way to Eleanor's uncle Raymond in Antioch, the army and the King and Queen were horrified by the unburied corpses of the previously slaughtered German army. Eleanor's Aquitainian vassal, Geoffrey de Rancon led the march to the crossing of Mount Cadmos. Louis chose to take charge of the rear of the column, where the unarmed pilgrims and the baggage trains marched. Geoffrey, unencumbered by baggage, chose to go further than planned, which left the slower train open to attack by Turks, who had been following behind.

The Turks had seized the summit of the mountain, and the French (both soldiers and pilgrims) having been taken by surprise, had little hope of escape. Those who tried were caught and killed, and many men, horses and baggage were cast into the canyon below the ridge. William of Tyre placed the blame for this disaster firmly on the baggage—which was considered to have belonged largely to the women traveling with Eleanor.

The official scapegoat for the disaster was Geoffrey de Rancon, who had made the bad decision to continue beyond the planned stop, and it was suggested that he be hanged (a suggestion which the King ignored). Since he was Eleanor's vassal, this did nothing for her popularity in Christendom. Eleanor's reputation was further sullied by her supposed affair with her uncle Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch when she decide to stay with him, probably angry with Louis. Eleanor was enraptured with the glamor of Antioch and with the reconnection to her uncle, who must have seemed much more interesting and worldly than her husband, "the monk."[3] Louis, in retaliation, had her dragged out of the castle and put on board a separate ship to go home.

Maritime innovations

The trip was not a total loss, however. While in the eastern Mediterranean, Eleanor learned about the maritime conventions developing there, which were the beginnings of what would become admiralty law. She introduced those conventions in her own lands, both on the island of Oleron in 1160 and later in England as well. She was also instrumental in developing trade agreements with Constantinople and ports of trade in the Holy Lands.

Annulment of first marriage

Even before the Crusade, Eleanor and Louis were becoming estranged. The city of Antioch had been annexed by Bohemond of Hauteville in the First Crusade, and it was now ruled by Eleanor's flamboyant uncle, Raymond of Antioch, who had gained the principality by marrying its reigning Princess, Constance of Antioch. Clearly, Eleanor supported his desire to re-capture the nearby County of Edessa, which was a major cause of the Crusade. In addition, having been close to him in their youth, she now showed excessive affection towards her uncle. While many historians today dismiss this as familial affection, amny at the time firmly believed the two to be involved in an incestuous and adulterous affair. Louis was directed by the Church to visit Jerusalem instead. When Eleanor declared her intention to stand with Raymond and the Aquitaine forces, Louis had her brought out by force. His long march to Jerusalem and back north debilitated his army, but her imprisonment disheartened her knights, and the divided Crusade armies could not overcome the Muslim forces. For reasons unknown, likely the Germans' insistence on conquest, the Crusade leaders targeted Damascus, an ally until the attack. Failing in this attempt, they retired to Jerusalem, and then home.

Home, however, was not easily reached. The royal couple, on separate ships due to their disagreements, were first attacked in May by Byzantine ships attempting to capture both (in order to take them to Byzantium, according to the orders of the Emperor). Although they escaped this predicament unharmed, stormy weather served to drive Eleanor's ship far to the south (to the Barbary Coast). Neither was heard of for over two months, at which point, in mid-July, Eleanor's ship finally reached Palermo in Sicily, where she discovered that both she and her husband had been given up for dead. The King still lost, she was given shelter and food by servants of King Roger of Sicily, until the Louis eventually reached Calabria, and she set out to meet him there. Later, at King Roger's court in Potenza, she learned of the death of her Uncle Raymond. This appears to have forced a change of plans, for instead of returning to France, they instead sought out the Pope Eugenius III in Tusculum, where he had been driven five months before by a Roman revolt.

The Pope did not, as Eleanor had hoped, grant a divorce; instead, he attempted to reconcile Eleanor and Louis, confirming the legality of their marriage, and proclaiming that no word could be spoken against it. Eventually, he maneuvered events so that Eleanor had no choice but to sleep with Louis in a bed specially prepared by the Pope. Eleanor thus conceived their second daughter, but the disappointment over the lack of a son only further endangered the marriage. Worried about being left with no male heir, facing substantial opposition to Eleanor from many of his Barons, and recognizing his wife's own desire for divorce, Louis had no choice but to bow to the inevitable.

Louis had lost the champion of his marriage in Abbot Suger, who had died in 1151. He and Eleanor met on March 11, 1152, at the royal castle of Beaugency to dissolve the marriage. Archbishop Hugh Sens, Primate of France, presided, and the archbishops of Bordeaux and Rouen were also present. Archbishop Sampson of Rheims acted for Eleanor. On March 21 the four archbishops, with the approval of Pope Eugenius, granted an annulment due to consanguinity within the fourth degree. [4] Their two daughters were declared legitimate, however, and custody of them awarded to Louis. Archbishop Sampson received assurances from Louis that Eleanor's lands would be restored to her.

Marriage to Henry II of England

Two lords—Theobald of Blois, ang Geoffrey of Anjou (brother of Henry, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy)—tried to kidnap Eleanor on her way to Poitiers in order to marry her and claim her lands, but she evaded them. As soon as she arrived in Poitiers, Eleanor sent envoys to Henry, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy, asking him to come at once and marry her. On Whit Sunday, May 18, 1152, six weeks after her annulment, Eleanor married Henry 'without the pomp and ceremony that befitted their rank'.[5] She was nearly 11 years older than he, and related to him more closely than she had been to Louis. One of Eleanor's rumored lovers had been Henry's own father, Geoffrey of Anjou, who had advised his son to avoid any involvement with her. But by uniting Eleanor's lands and Henry's, his dominion became the greatest in Europe, much larger than that of France.

In the nearly two months she lived in Aquitaine before Henry arrived to marry her, she could rule in her own name, adjudicate in her own name and did so with the full support of her people. She was the lord of Aquitaine, due to the brilliant strategy of her father in insisting that she alone could claim the duchy. This right of rule for women was diminishing until it would rise again in England with Queen Elisabeth I, daughter of Henry VIII.

The popularity of the royal couple was linked to the ancient prophecies of Merlin, popular in Europe in the twelfth century, which were often thought to refer to the family of Henry II: "The eagle of the broken covenant, shall rejoice in her third nesting." Eleanor was thought to be the eagle, the broken covenant was the dissolution of her marriage to Louis, and the third nesting was thought to be the birth of her third son, Richard who would later be king.[6]

Over the next 13 years, she bore Henry five sons and three daughters: William, Henry, Richard, Geoffrey, John, Matilda, Eleanor, and Joanna. [7]

Henry had a reputation for philandering and was by no means faithful to his wife. Their son, William, and Henry's illegitimate son, Geoffrey, were born just months apart. Henry fathered other illegitimate children throughout the marriage. Eleanor appears to have taken an ambivalent attitude toward these affairs: for example, Geoffrey of York, an illegitimate son of Henry and a prostitute named Ykenai, was acknowledged by Henry as his child and raised at Westminster in the care of the Queen.

is Geof of York the same as the Geof born months apart from william? this is not clear.

The period between Henry's accession and the birth of Eleanor's youngest son was turbulent. Aquitaine, as was the norm, defied the authority of Henry as Eleanor's husband. Attempts to claim Toulouse, the rightful inheritance of Eleanor's grandmother and father, were made, ending in failure; the news of Louis of France's widowhood and remarriage was followed by the marriage of Henry's son (young Henry) to Louis' daughter Marguerite; and, most climatically, the feud between the King and Thomas Becket, his Chancellor, and later his Archbishop of Canterbury. Little is known of Eleanor's involvement in these events, however. By late 1166, and the birth of her final child, however, Henry's notorious affair with Rosamund Clifford had become known, and her marriage to Henry appears to have become terminally strained.

the above Par. is too thick

The year 1167 saw the marriage of Eleanor's third daughter, Matilda, to Henry the Lion of Saxony; Eleanor remained in England with her daughter for the year prior to Matilda's departure to Normandy in September. Afterwards, Eleanor proceeded to gather together her movable possessions in England and transport them on several ships in December to Argentan. At the royal court, celebrated there that Christmas, she appears to have agreed to a separation from Henry. Certainly, she left for her own city of Poitiers immediately after Christmas. Henry did not stop her; on the contrary, he and his army personally escorted her there, before attacking a castle belonging to the rebellious Lusignan family. Henry then went about his own business outside Aquitaine, leaving Earl Patrick (his regional military commander) as her protective custodian. When Patrick was killed in a skirmish, Eleanor (who proceeded to ransom his captured nephew, the young William Marshal), was left in control of her inheritance. Eleanor assumed control of the duchy of Aquitaine with Henry's support, after the death of his mother, Mathilda, in 1167. Perhaps, Henry had had enough of strong willed women and wished to be free.

At a small cathedral still stands the stained glass commemorating Eleanor and Henry with a family tree growing from their prayers. Away from Henry, Eleanor was able to encourage the cult of courtly love at her court. Apparently, however, both King and church expunged the records of the actions and judgments taken under her authority. A small fragment of her codes and practices was written by Andreas Capellanus.

Henry concentrated on controlling his increasingly-large empire, badgering Eleanor's subjects in attempts to control her patrimony of Aquitaine and her court at Poitiers. Straining all bounds of civility, Henry caused the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket at the altar of the church in 1170 (though there is considerable debate as to whether it was truly Henry's intent to be permanently rid of his archbishop). This aroused Eleanor's horror and contempt, along with most of Europe's.

Eleanor's focus now turned solely to her children and their fortunes, not just with their own advancement but also using them as a weapon against Henry. This was the end of a great love affair that produced a line of many members of royal families in Europe.

Revolt and capture

In the spring of 1172, while Eleanor looked on, fifteen-year-old Richard was installed as duke of Aquitaine. His brother, 'young Henry', originally prematurely crowned by the Archbishop of York in 1170, was crowned a second time a few months later in the autumn of 1172.

In March 1173, aggrieved at his lack of power and egged on by his father's enemies, the younger Henry launched the failed Revolt of 1173-1174. He fled to Paris. From there the younger Henry, devising evil against his father from every side by the advice of the French King, went secretly into Aquitaine where his two youthful brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, were living with their mother, and with her connivance, so it is said, he incited them to join him'.[8] The Queen sent her younger sons to France 'to join with him against their father the King'.[9] Once her sons had left for Paris, Eleanor encouraged the lords of the south to rise up and support them.[10] Sometime between the end of March and the beginning of May, Eleanor left Poitiers to follow her sons to Paris but was arrested on the way and sent to the King in Rouen, her actions could have been considered treasonous, and thus punishable by death. The King did not announce the arrest publicly. For the next year, her whereabouts are unknown, in all she suffered captivity for fifteen years. On July 8, 1174, Henry took ship for England from Barfleur. He brought Eleanor on the ship. As soon as they disembarked at Southampton, Eleanor was taken away either to Winchester Castle or Sarum Castle and held there.

Years of imprisonment 1173–1189

Eleanor was imprisoned for the next fifteen years, much of the time in various locations in England. During her imprisonment, Eleanor had become more and more distant with her sons, especially Richard (who had always been her favorite). She did not get the chance to see her sons very often during her imprisonment, though she was released for special occasions such as Christmas. About four miles from Shrewsbury and close by Haughmond Abbey is "Queen Eleanor's Bower," the remains of a triangular castle which is believed to have been one of her prisons.

Henry lost his great love of three years, Rosamund Clifford, in 1176. While he was supposedly contemplating divorce from Eleanor, he flaunted Rosamond. This notorious affair caused a monkish scribe with a gift for Latin to transcribe Rosamond's name to "Rosa Immundi," or "Rose of Unchastity." Likely, Rosamond was one weapon in Henry's efforts to provoke Eleanor into seeking an annulment (this flared in October 1175). Had she done so, Henry might have appointed Eleanor abbess of Fontevrault (Fontevraud), requiring her to take a vow of poverty, thereby releasing her titles and nearly half their empire to him. Eleanor was much too wily to be provoked into this, or to seek Rosamond's death: "In the matter of her death the Almighty knows me innocent. When I had power to send her dead, I did not; and when God wisely chose to take her from this world I was under constant watch by Henry’s spies."[11]. Nevertheless, rumors persisted, perhaps assisted by Henry's camp, that Eleanor had poisoned Rosamund. No one knows what Henry believed, but he did donate much money to the Godstow Nunnery in which Rosamund was buried.

In 1183, Henry the Young tried again. In debt and refused control of Normandy, he tried to ambush his father at Limoges. He was joined by troops sent by his brother Geoffrey and Philip II of France. Henry's troops besieged the town, forcing his son to flee. Henry the Young wandered aimlessly through Aquitaine until he caught dysentery. On Saturday, 11 June 1183, the Young King realized he was dying and was overcome with remorse for his sins. When his father's ring was sent to him, he begged that his father would show mercy to his mother, and that all his companions would plead with Henry to set her free. The King sent Thomas of Earley, Archdeacon of Wells, to break the news to Eleanor at Sarum.[12] Eleanor had had a dream in which she foresaw her son Henry's death. In 1193 she would tell Pope Celestine III that she was tortured by his memory. Eleanor lost Henry, Henry lost his popularity and they both lost young Henry to an early death.

In 1183, Philip of France claimed that certain properties in Normandy belonged to young Henry's widow, Marguerite of France (born 1158) but Henry insisted that they had once belonged to Eleanor and would revert to her upon her son's death. For this reason Henry summoned Eleanor to Normandy in the late summer of 1183. She stayed in Normandy for six months. This was the beginning of a period of greater freedom for the still supervised Eleanor. Eleanor went back to England probably early in 1184.[13] Over the next few years Eleanor often traveled with her husband and was sometimes associated with him in the government of the realm, but still had a custodian so that she was not free.

Finally, her sons Richard and John joined with Philip of France in a final rebellion against king Henry, who capitulated on July 4, 1189, two days afterwards he died alone. He was buried at Fontevrault. This began the use of Fontevrault for royal burials.

This commenced the final period of Eleanor's life, freed by Henry's death, to once again be the lord of Aquitaine and the dowager queen of England involved in the lives of her children and grandchildren and their futures.

Regent of England

Upon Henry's death on July 6 1189, just days after suffering an injury from a jousting match, Richard was his undisputed heir. One of his first acts as king was to send William the Marshal to England with orders to release Eleanor from prison, but her custodians had already released her.[14] Eleanor took full advantage of her role as Queen Mother when Richard assumed the throne. She was liberated in many ways by Henry's death. She began her most fruitful life in widowhood.

Eleanor rode to Westminster and received the oaths of fealty from many lords and prelates on behalf of the new King. She moved swiftly to gain the loyalty to Richard of the barons and free men alike, and helped with his great homecoming for the coronation at Westminster on September 3, 1189.

Richard was more interested in going on crusade and left his mother to rule England in Richard's name, signing herself as 'Eleanor, by the grace of God, Queen of England'. On August 13, 1189, Richard sailed from Barfleur to Portsmouth, and was received with enthusiasm. She ruled England as regent in his absence. During 1190 to 1191 Eleanor traveled through Europe to strengthened their alliances with other rulers.

She arranged his wedding to Berengaria, princess of Navarre, which took place in Cyprus in May of 1191 as he traveled to the Holy Land. And when he was taken prisoner in 1193 , she personally negotiated his ransom of a staggering 100,000 marks, by going to Germany herself. She also thwarted a conspiracy between her younger son John and Philip Augustus by intimidating John. At seventy years old she continued to travel and joined Richard in paying homage to Emperor Henry VI at Mainz, thus securing his loyalty to Richard's interests above those of Philip Augustus and John. On April 17, 1194 she sat as his equal (not Berengaria) as he once more took his crown.

Her daughter, Joanna, took a second husband, Raymond VI of Toulouse, satisfying her long held desire to connect Toulouse to the Aquitaine. Through Richard's support, her grandson Otto Brunswick, duke of Poitou, became the Holy Roman Emperor. Henry II had long desired this coveted position.

In 1199, Richard wearing no armor, was struck by an arrow. As the archer pulled his bow, Richard, knew his fate, he turned and forgave the man who would kill him. He died with his mother at his side on April 6, 1199. Later that year her daughter, Joanna and her newborn son died.

Later life

Eleanor survived Richard and lived well into the reign of her youngest son King John.

In 1199, under the terms of a truce between King Philip II of France and King John, it was agreed that Philip's twelve-year-old heir Louis would be married to one of John's nieces of Castile. John deputed Eleanor to travel to Castile to select one of the princesses. Now 77, Eleanor set out from Poitiers. Just outside Poitiers she was ambushed and held captive by Hugh IX of Lusignan, which had long ago been sold by his forebears to Henry II. Eleanor secured her freedom by agreeing to his demands and journeyed south, crossed the Pyrenees, and traveled through the Kingdoms of Navarre and Castile, arriving before the end of January, 1200.

King Alfonso VIII and Queen Leonora of Castile had two remaining unmarried daughters, Urraca and Blanche. Eleanor selected the younger daughter, Blanche. She stayed for two months at the Castilian court. Late in March, Eleanor and her granddaughter Blanche journeyed back across the Pyrenees. When she was at Bordeaux where she celebrated Easter, the famous warrior Mercadier came to her and it was decided that he would escort the Queen and Princess north. "On the second day in Easter week, he was slain in the city by a man-at-arms in the service of Brandin",[15] a rival mercenary captain. This tragedy was too much for the elderly Queen, who was fatigued and unable to continue to Normandy. She and Blanche rode in easy stages to the valley of the Loire, and she entrusted Blanche to the Archbishop of Bordeaux, who took over as her escort. The exhaused Eleanor went to Fontevrault, where she remained. In early summer, Eleanor was ill and John visited her at Fontevrault.

Eleanor was again unwell in early 1201. When war broke out between John and Philip, Eleanor declared her support for John, and set out from Fontevrault for her capital Poitiers to prevent her grandson Arthur[16] John's enemy, from taking control. Arthur learned of her whereabouts and besieged her in the castle of Mirabeau. As soon as John heard of this he marched south, overcame the besiegers and captured Arthur. Eleanor then returned to Fontevrault where she took the veil as a nun. By the time of her death she had outlived all of her children except for King John and Queen Leonora.

Her legacy

Eleanor beloved by her Aquitainian subjects was nonetheless misjudged by the French as frivolous, and immoral. But Eleanor, the mature woman, mother, and grandmother, exhibited great tenacity, political wisdom and amazing energy well past her eighty years. She could easily be called the "grandmother of Europe" with the well orchestrated marriages of her children and grandchildren. Through her efforts, unity and peace prevailed through much of Europe. The Plantagenet reign lasted 300 years with her support.

She was generous in support of religious orders, especially Fontevrault. “She was beautiful and just, imposing and modest, humble and elegant”; and, as the nuns of Fontevrault wrote in their necrology, a queen “who surpassed almost all the queens of the world.”

Eleanor died in 1204 and was entombed in Fontevrault Abbey near her husband Henry and son Richard. Her tomb effigy shows her reading a Bible and is decorated with magnificent jewelry. She was the patroness of such literary figures as Wace, Benoît de Sainte-More, and Chrétien de Troyes.

In historical fiction

Eleanor and Henry are the main characters in the play The Lion in Winter, by James Goldman, which was made into a film starring Peter O'Toole and Katharine Hepburn, and remade for television in 2003 with Patrick Stewart and Glenn Close. The depiction of her in the play and film Becket contains historical inaccuracies, as acknowledged by the author, Jean Anouilh. In 2004, Catherine Muschamp's one-woman play, Mother of the Pride, toured the UK with Eileen Page in the title role. In 2005, Chapelle Jaffe played the same part in Toronto.

Eleanor appears briefly in the BBC production of Ivanhoe portrayed by Sian Phillips. She is the subject of E. L. Konigsburg's children's book A Proud Taste for Scarlet and Miniver. Her life is chronicled in three books by Sharon Kay Penman When Christ and His Saints Slept, Time and Chance, and The Devil's Brood. The novel The Book of Eleanor by Pamela Kaufman tells the story of Eleanor's life from her own point of view. She dictates her memoirs in Robert Fripp's Power of a Woman. Beloved Enemy, a novel by Ellen Jones, portrays her marriage to Louis VII and the first decade of her marriage to Henry II. The character "Queen Elinor" appears in William Shakespeare's King John, along with other members of the family. Kristiana Gregory explored Eleanor's early life in her 2002 juvenile work Eleanor: Crown Jewel of Aquitaine. Another novel, Duchess of Aquitaine, was published by author Margaret Ball in 2006.

Although never portrayed directly onscreen, nor mentioned by name, Eleanor is referenced often in the Disney animated film Robin Hood. The comically spoiled Prince John (Peter Ustinov) is constantly being reminded of his mother by his scribe, Sir Hiss. Even an oblique reference to her, renders John into an infantile, thumb-sucking state, probably because (as he sulkily states) "Mother always did love Richard best."

Eleanor does appear (played by Jill Esmond) as a recurring character in several episodes of the classic television program The Adventures of Robin Hood, whom Robin aids in her efforts to raise King Richard's ransom and thwart Prince John's schemes.

Notes

- ↑ The story that she and her ladies dressed as Amazons is disputed by historians.

- ↑ Some suggest that it could have been in penance for the deaths at Vitry, others that it could have been to seek adventure and see new sights in a righteous cause.

- ↑ Wheeler (year)

- ↑ Consanguinity is defined as a relationship by blood or by a common ancestor. Eleanor and Louis were third cousins, once removed and shared common ancestry with Robert II of France.

- ↑ Chronique de Touraine

- ↑ Eleanor of Aquitaine, Alison Weir

- ↑ John Speed, in his 1611 work, History of Great Britain, mentions the possibility that Eleanor had a son named Philip, who died young. His sources no longer exist and he alone mentions this birth. Weir, Alison, Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Life, pages 154-155, Ballantine Books, 1999

- ↑ William of Newburgh

- ↑ Roger of Hoveden

- ↑ Eleanor of Aquitaine. Alison Weir 1999

- ↑ Power of a Woman, chapter 22.

- ↑ Ms. S. Berry, Senior Archivist at the Somerset Archive and Record Service, identified this "archdeacon of Wells" as Thomas of Earley, noting his family ties to Henry II and the Earleys' philanthropies (Power of a Woman, ch. 33, and endnote 40).

- ↑ Eleanor of Aquitaine. Alison Weir 1999

- ↑ Eleanor of Aquitaine. Alison Weir 1999.

- ↑ Roger of Hoveden

- ↑ Son of Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, Eleanor and Henry's fourth son and Constance, the Duchess of Brittany

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brooks, Polly Schover, and Polly Brooks. Queen Eleanor: Independent Spirit of the Medieval World, 1999. ISBN 978-0395981399

- Calmel, Mireille. 'Le lit d'Aliénor, Pocket publ. 2003. ISBN 978-2266126878

- Duby, George. Women of the Twelfth Century, Volume 1 : Eleanor of Aquitaine and Six Others, University of Chicago Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0226167800

- Gregory, Kristiana. The Royal Diaries, Eleanor Crown Jewel of Aquitaine. Scholastic, inc., 2002. ISBN 978-0439164849

- Kelly, Amy. Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings, Harvard university Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0674242548

- Konigsburg, E. L. A Proud Taste For Scarlet and Miniver. Aladdin, 2001. ISBN 978-0689846243

- Meade, Marion. ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE A Biography, 1997. ASIN: B000GLDMDK

- Owen, D.D.R. Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen and Legend. Oxford: Blackwell Publ., 1996. ISBN 978-0631201014

- Plaidy, Jean. The Courts of Love, Three Rivers Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1400082506

- Seward, Desmond. Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Mother Queen, Dorset Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0880290555

- Weir, Alison. Eleanor of Aquitaine, Ballantine Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0345434876

- Wheeler, Bonnie and John Carmi Parsons. Eleanor of Aquitaine: Lord and Lady, Palgrave Macmillan; 1 edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0312295820

- Wheeler, Bonnie. Medieval Heroines in History and Legend, part II. The Teaching Company, 2002. ISBN 1-56585-523-X

External link

- William IX, William X, and Eleanor of Aquitaine — the House of Aquitaine and its relations with the Houses of Toulouse, England, and France.

| Preceded by: William X |

Duchess of Aquitaine with Louis and Henry I 1137–1168 |

Succeeded by: Richard I |

| Countess of Poitiers with Louis and Henry I 1137–1153 |

Succeeded by: William | |

| Preceded by: Adelaide de Maurienne |

Queen of France 1137 – 1152 |

Succeeded by: Constance of Castile |

| Preceded by: Matilda of Boulogne |

Queen Consort of England 25 October, 1154 - 6 July, 1189 |

Succeeded by: Berengaria of Navarre |

| Preceded by: Emma of Normandy |

Queen Mothers 1189 - 1204 |

Succeeded by: Isabella of Angoulême |

George, Duke of Cumberland (1702-1707) · Mary of Modena (1685-1688) · Catherine of Braganza (1662-1685) · Henrietta Maria of France (1625-1649) · Anne of Denmark (1603-1619) · Philip II of Spain (1554-1558) · Guilford Dudley (1553) · Catherine Parr (1543-1547) · Catherine Howard (1540-1542) · Anne of Cleves (1540) · Jane Seymour (1536-1537) · Anne Boleyn (1533-1536) · Catherine of Aragon (1509-1533) · Elizabeth of York (1486-1503) · Anne Neville (1483-1485) · Elizabeth Woodville (1464-1483) · Margaret of Anjou (1445-1471) · Catherine of Valois (1420-1422) · Joanna of Navarre (1403-1413) · Isabella of Valois (1396-1399) · Anne of Bohemia (1383-1394) · Philippa of Hainault (1328-1369) · Isabella of France (1308-1327) · Marguerite of France (1299-1307) · Eleanor of Castile (1272-1290) · Eleanor of Provence (1236-1272) · Isabella of Angoulême (1200-1216) · Berengaria of Navarre (1191-1199) · Eleanor of Aquitaine (1154-1189) · Matilda of Boulogne (1135-1152) · Adeliza of Louvain (1121-1135) · Matilda of Scotland (1100-1118) · Matilda of Flanders (1066-1083)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.