Czechoslovakia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

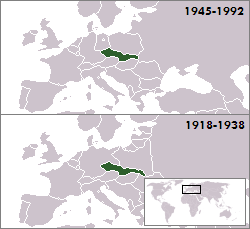

Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak: Československo, or (increasingly after 1990) in Slovak Česko-Slovensko) was a country in Central Europe that existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992 (with a government-in-exile during the World War II period). On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia peacefully split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. After WWII, active participant in Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), Warsaw Pact, United Nations and its specialized agencies; signatory of conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

After WWII, monopoly on politics held by Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Gustáv Husák elected first secretary of KSC in 1969 (changed to general secretary in 1971) and president of Czechoslovakia in 1975. Other parties and organizations existed but functioned in subordinate roles to KSC. All political parties, as well as numerous mass organizations, grouped under umbrella of the National Front.

Basic Facts

Form of statehood:

- 1918–1938: democratic republic

- 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by Germany in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, Slovak and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by Hungary, while the Zaolzie region went under Poland's control

- 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the independent Slovakia, although Czechoslovakia was never officially dissolved; its exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, was based in London. Following the German invasion of Russia, the Soviet Union recognized the exiled government as well.

- 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with Communist ministers charting the course

- 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy

- 1960 on: the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

- 1969–1990: a federal republic consisting of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic

- 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic

Official Names

- 1918–1920: Czecho-Slovak Republic or Czechoslovak Republic (abbreviated RČS); short form Czecho-Slovakia or Czechoslovakia

- 1920–1938 and 1945–1960: Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR); short form Czechoslovakia

- 1938–1939: Czecho-Slovak Republic; Czecho-Slovakia

- 1960–1990: Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR); Czechoslovakia

- April 1990: Czechoslovak Federative Republic (Czech version) and Czecho-Slovak Federative Republic (Slovak version),

- afterwards: Czech and Slovak Federative Republic (ČSFR, with the short forms Československo in Czech and Česko-Slovensko in Slovak)

History

Inception

Czechoslovakia came into existence in October 1918 as one of the successor states of Austria-Hungary following the end of World War I. It comprised the territory of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia and some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. On October 16, 1918, Emperor Charles I attempted to rescue the crumbling Habsburg Monarchy by proposing a federal monarchy, but two days later, US President Woodrow Wilson in January 1918 issued Fourteen Points, proclaiming an independent state of Czechs and Slovaks. The document was drawn up by Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, who united Czechs and Slovaks living abroad around the common goal of a joint state and was the driving force behind the Czechoslovak resistance movement based outside the country. It was addressed to Wilson and the US Government in response to the foreign policy of Emperor Charles I – Czechs and Slovaks were not satisfied with an “autonomy” within the Habsburg Monarchy but pursued complete independence. The proclamation was a blueprint for the constitution of the state-in-the-works, vowing broad democratic rights and freedoms, separation of state from Church, expropriation of land, and abolishment of the class system.

On October 28, 1918, Alois Rašín, Antonín Švehla, František Soukup, Jiří Stříbrný, and Vavro Šrobár, known as the "Men of October 28th", formed a provisional government, and two days later, Slovakia endorsed the marriage of the two countries, with Masaryk elected president.

World War II

End of State

Satisfaction among individual ethnic groups within the new state varied, as Germans, Slovaks, and Slovakia's ethnic Hungarians grew resentful of the political and economic dominance of the Czechs. These ethnic groups, as well as Ruthenians and Poles, felt disadvantaged in a centralized state that was reluctant to safeguard political autonomy for all of its constituents. This policy, combined with an increasing Nazi propaganda, particularly in the industrialized German speaking Sudetenland (the German-border regions of Bohemia and Moravia) and its calls for the creation of a new province, Deutschösterreich (German Austria) and later Deutschböhmen (German Bohemia), fueled the growing unrest in the years leading up to World War II.[1]) Many Sudeten Germans rejected affiliation with Czechoslovakia because their right to self-determination coined in the Fourteen Points had not been honored.

Following the German annexation of Austria, referred to as the Anschluss, the Sudetenland would be Adolf Hitler's next demand. The Munich Agreement, signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Hitler, Great Britain—Neville Chamberlain, Italy—Benito Mussolini, and France—Édouard Daladier, robbed Czechoslovakia of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, where most of the country's border defences were situated. Wehrmacht troops occupied the Sudetenland in October 1938. Within ten days, 1,200,000 Czechs and Slovaks living there were told to leave their homes, and the severely weakened Czechoslovak Republic was forced to grant major concessions to the non-Czechs.Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and Emil Hácha, a highly respected lawyer by training and independent thinker, was appointed president. Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without taking up. In November, the First Vienna Award handed over part of southern Slovakia to Hungary.

On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Hitler; the same day, Slovakia declared independence and became an ally of Nazi Germany, which provided Hitler with a pretext to occupy Bohemia and Moravia on grounds that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within and his administration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia would forestall chaos in Central Europe. Hácha described the signing away of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany, for which he had been traditionally labeled as national traitor, as follows: “It’s possible to withstand Hitler’s yelling, because a person who yells is not necessarily a devil. But Göring [Hitler’s right hand], with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful Prauge to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, capable of carrying out his threat, was speaking to me.” [2] Göring further asked Hácha: “You do not want or cannot understand the Führer, who wishes that lives of thousands of Czech people are spared?” [3]

The president had been subjected to enormous psychological pressure in the course of which he collapsed repeatedly. The next morning, Wehrmacht occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that “We would have shed a lot of blood.” [4] Czechoslovakia’s factories thus began churning out equipment for the Third Reich.

Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an anti-government uprising that was quickly crushed by Germany.

Resistance Movement

On October 28, 1939, the 21st anniversary of the establishment of the country, Czechoslovakia, emboldened by hopes for an early restoration of the independence, was swept by massive demonstrations. Medical student Jan Opletal was killed in Prague in confrontations with the occupants, which spurred further unrest that provoked Nazi terror targeting students, spontaneous executions of student leaders, and the closure of universities. These reprisals signaled that continued open encounter with the occupation forces was not feasible; therefore, resistance movement shifted to underground organizations and networks. The goal of the London-based exiled government, headed by Edvard Beneš, in conjunction with efforts of national and foreign-based Czechoslovak representative offices, was to restore the independent Czechoslovakia. The government oversaw formation of Czechoslovak units in Poland, France and Great Britain composed of recruits from the ranks of exiled Czechoslovak citizens.

On the home turf, resistance movement continued chiefly through massive demonstrations, which reached an apex in 1941. The society was split in three streams with respect to their stance on the Nazi occupation: the largest chunk of the population comprised people who passively rejected the occupation and would swing both ways. Then there were those who supported the resistance movement, and, lastly, resistance movement groups and organizations seeking the restoration of the independent Czechoslovak Republic. However, widespread arrests severely disrupted the underground networks and cut off radio networks between domestic and foreign components of the resistance movement, which were then reestablished by paratroopers dispatched into the Protectorate.

Operation Anthropoid

The Czechoslovak-British Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination of the top Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich, the chief of RSHA, an organization that included the Gestapo (Secret Police), SD (Security Agency) and Kripo (Criminal Police). Heydrich was the mastermind of the purge of Hitler's opponents as well as the genocide of Jews. Being a valued political ally, advisor and friend of the dictator, he had his hands in most of Hitler's intrigues and was feared by Nazi generals. Thanks to his reputation as the liquidator of resistance movements in Europe, he was sent to Prague in September 1941 as the Protector of Bohemia and Moravia to make order. The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was of strategic importantance to Hitler’s plans, and Heydrich, dubbed the “Butcher of Prague”, "The Blond Beast" or "The Hangman", wasted no time upon his arrival, handing out death sentences for Czech military officials, resistance movement fighters and political figures the day after his arrival in Prague.

With the fighting spirit in the Protectorate at lull, the exiled military officials started planning an act that would stir up the nation’s consciousness — six Czech and one Slovak paratroopers were chosen for the assassination of Heydrich, and two of them— Czech Josef Valčík and Slovak Josef Gabčik, carried out the act. Heydrich died of complications following surgery. The Gestapo tracked the paratroopers’ contacts and eventually discovered the paratroopers’ hideaway in a Prague church. Three of them died in a shootout, trying to buy time for the others so that they could dig out an escape route. The Gestapo found out and used tear gas and water to chase the remaining four out, who used their last bullets to take their lives rather than fall in the Nazi hands alive.

Heydrich’s successor Karl Herrmann Frank had 10,000 Czechs executed as a warning, and two villages that assisted the paratroopers were leveled down, with the adults executed and young children sent to German families for re-education. The combined actions of the Gestapo and its confidantes virtually paralyzed the Czech resistance movement; on the other hand, the assassination bolstered Czechoslovakia’s prestige in the world and was crucial to the country’s securing of demands for an independent republic following the end of WWII.

End of War

Toward the end of the war, partisan movement was gaining momentum, and once the Allies were on the winning side, the political orientation of Czechoslovakia was high on the agenda of the two most influential exiled centres–the government in London and the communist officials in Moscow. Both saw the agreement on friendship, mutual assistance and postwar cooperation between Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union as a means to stem German expansion and the Soviet Union’s mingling into Czechoslovakia's internal affairs. The country was liberated by the Soviet Union's Red Army and partly by the US Army on May 9.

Communist Czechoslovakia

Communist Takeover

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reestablished. Carpathian Ruthenia has been occupied by and in June 1945 formally ceded to the Soviet Union, while ethnic Germans inhabiting the Sudetenland were expelled in an act of retaliation coined by the Beneš Decrees. Wartime "traitors" and collaborators accused of treason along with ethnic Germans and Hungarians were expropriated, with those ethnic Germans and Hungarians who switched to German and Hungarian citizenship during the occupation stripped of their national identity. These provisions were lifted for the Hungarians in 1948. Altogether around 90% of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia was made leave. Although the decrees specified that the sanctions did not apply to anti-fascists, the decisions were up to local municipalities. Some 250,000 Germans, many married to Czechs and anti-fascists, remained. The Beneš Decrees continue to fuel controversy between nationalist groups in the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, and Hungary. [5].

The Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia was facilitated by the liberation of most of the country by the Red Army and by the overall social and economic downturn in Europe. Marshall’s Plan, authored by US State Secretary George Marshall in June 1947, addressed the European needs with an offer of financial and material aid and thus stabilization of the region but was turned down by the Soviet Union and, consequently, by its satellites, including Czechoslovakia. In the 1946 parliamentary election, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia emerged as the winner in the Czech lands while the Democratic Party won in Slovakia, and in February 1948, the Communists seized power and sealed the country’s fate for the next 41 years. Terror reminiscent of Hitler’s Germany followed, with execution of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, forceful collectivization of agricutlrue, censorship, and land grabs. Economy was controlled by five-year plans and the industry was overhauled in compliance with Soviet wishes to focus on heavy industry, in which Czechoslovakia had been traditionally weak. The economy retained momentum vis-à-vis its Eastern European neighbors but grew increasingly weak vis-a-vis Western Europe. Atheism became the official spiritual doctrine.

Year 1960 saw the declaration of the victory of socialism, with small businesses stamped out and the country’s name changed to the Czechoslovak Soicialist Republic. In early 60s, the socialist planning brought about an economic crisis and reshuffles in the Communist leadership. Economic reforms were put in place that grew into the reform of the overall political system. Slovakia’s Alexander Dubček took over with the doctrine of ‘socialism with human face, called the Prague Spring, but these efforts were crushed under the tanks of the Warsaw Pact armies on August 21, 1968.

Prague Spring was replaced by the period of normalization, with political, military and union purges and the repeal of reforms, which thrust the country back into 1950s. The dissident movement, symbolized by the future Czech President Václav Havel, worked underground to counter the system and drew up Charter 77, a document that demanded human rights. The government responded with a prohibition of professional employment for the dissidents, higher education for their children, police harassment and prison time. All artists who wanted to continue working in their field were forced to sign the government-issued Anti-Charter.

In 1969, Czechoslovakia became a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic in a move to eliminate economic inequities between the two parts. A number of ministries were divided to cater to each part; however, the centralized grip of the Communist Party diminished the effects of federalization.

In the 80s, the regime again grappled with a stifling economic crisis, and the revolutions in neighboring socialist countries encouraged Czechoslovakia to take steps toward democracy.

Velvet Revolution

1989 in the World

Mikhail Gorbatchev’s address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York, in which he endorsed the rights for all nations to shape their destiny, was among the first signs of the worldwide crumbling of the Communist empire. Gorbatchev followed through with a unilateral withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops from Europe and Asia and rehabilitated victims of Stalin's rule. Elections in March 1989 saw Communist candidates defeated, which spurred calls for the secession of the small Soviet republics from the Soviet Union. Hungary started taking steps toward democracy by allowing other than Commmunist political parties, but Communist authorities in Prague brutally dispersed ad hoc anti-regime demonstrations and Romania imprisoned journalists brave enough to criticize its President Ceausescu. Bloodbath occurred at East Berlin's infamous Berlin Wall. In Poland, a series of strikes forced the government to forge a deal with Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarita movement. One million students in Beijing took to the streets hoping that Gorbachev’s visit to China would be followed by reforms; however, thousands of them were massacred at the Tchien-an-men Square.

November 1989

In Prague, the demonstrations were planned for November 17 in commemoration of the 1939 Nazi attack against university dormitories in Czechoslovakia and the subsequent closure of universities for three years. That day in 1989, however, saw not only water hoses and spontaneous arrests but also sheer violence targeting young people, who were brutally beaten by the police who blocked off all escape routes at Prague's Narodni Trida (National Avenue). This set in motion the Velvet Revolution, as the events that unseated Communism in the country came to be known, with main being Prague students, who solicited support of artists and actors. The protests soon spread throughout the country, and in the second half of November, Slovak artists, scientists and prominent figures set up the Public Against Violence movement in Slovakia, which would become the vehicle for the opposition movement there, with actor Milan Kňažko and Ján Budaj among the key figures. In the Czech lands, Václav Havel and other outspoken members of Charter 77 and dissident organizations established the Civic Forum.

As Communist governments in neighboring countries were being toppled, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia announced in late November an intention to hand over power. Borders with Western Europe were open in early December, and a week later, President Gustáv Husák appointed the first government composed of largely non-Communists since 1948, and resigned. Alexander Dubček, who played a crucial role in the Prague Spring, became the voice of the federal parliament and Václav Havel the President. In June 1990, the first democratic elections since 1946 were held.

pict of Havel, Dienstbier, Knazko, Prague demonstrations

Toward Velvet Divorce

Elections in June 1992 saw a significant makeover of the cabinet, until that time comprising mostly former dissidents. Even prior to this, Slovakia's creation fo the Foreign Relations Ministry in 1990 had signaled intensified independence efforts. The Czech Republic followed suit in 1992. In 1992, the mounting nationalist tensions led to dissolution of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia on January 1, 1993. This was preceded by the departure of most former dissidents from politics in .

Dne 29. prosince 1992 podepsali ministři Moravčík, Zieleniec a Kňažko dohody, které řešily rozdělení majetku i pracovníků federálního ministerstva zahraničí mezi nástupnická ministerstva. Vznik samostatné české a slovenské diplomacie probíhal v jednotlivých republikách poněkud odlišně. Slovenské ministerstvo zahraničních věcí budovalo od roku 1990 svou strukturu prakticky od základů. České ministerstvo mezinárodních vztahů sloužilo jako malá organizační jednotka, jejímž úkolem bylo především vytvoření legislativních podmínek, které by umožnily po rozpadu Československa bezproblémový přechod české diplomacie na mezinárodní scénu.

Dělení struktur a pracovníků v ústředí Po vzniku samostatné České republiky převzalo Zieleniecovo ministerstvo podstatnou část struktur, zázemí i pracovníků bývalého federálního ministerstva zahraničí. Jeho ústředí v Černínském a Toskánském paláci se stala hlavními sídly české diplomacie. Spolu s budovami převzalo české ministerstvo i většinu federálních zaměstnanců. Přestože jejich poměr kvantitativně odrážel národnostní složení federace, řada Slováků se v Praze naturalizovala a zvolila možnost stát se občany samostatné České republiky. Z necelých 800 zaměstnanců federálního ministerstva působících v ústředí jich tak více než 700 přešlo do služeb České republiky a rovnoměrně pokrylo všechny oblasti činnosti úřadu. Vznik samostatného českého státu nevyvolal potřebu masivního náboru nových zaměstnanců a nepřinesl tak zásadní změnu struktury ministerstva jako po pádu komunistického režimu.

[Josef Zieleniec] Dělení majetku v zahraničí Dělení majetku v zahraničí usnadnila skutečnost, že československé zastoupení v hlavních městech cizích států často využívalo několika budov. Vedle velvyslanectví a rezidence velvyslance měla ve významnějších centrech samostatnou budovu i obchodní mise. Po rozdělení federace tak bylo často možné otevřít samostatné budovy české i slovenské ambasády. Například v Havaně převzala Česká republika budovu velvyslanectví, naopak Slovensko využilo rezidenci velvyslance. Jen v jednotlivých případech musela Česká republika hledat nové sídlo svého zastupitelského úřadu. Sem patřila naše velvyslanectví v Ottawě, Římě a Soulu. Principem hodnotového dělení byl poměr počtu obyvatel, tedy 2:1. Hodnota nemovitého majetku v zahraničí byla oceněna nezávislou globálně působící realitní firmou. Vzájemným jednáním obou stran pak byla „politická hodnota“ té které destinace vyvážena v destinaci podobného významu jinde.

Vzájemné vztahy První otázkou, kterou oba nástupnické státy musely na mezinárodním poli řešit, byla problematika vzájemných vztahů. Rozdělení federace proběhlo bez výraznějších problémů a samostatné republiky mezi sebou udržují nadstandardně přátelské vztahy. Ve srovnání s rozpadem řady mnohonárodnostních států, k němuž v 90. letech došlo, vyřešila česká a slovenská strana rozpad společné federace velmi citlivě a nenásilně. Rozdělení Československa proběhlo bezkonfliktně m.j. i díky expertům z MZV, kteří na základě analýz rozpadu některých států poskytovali vedení státu i klíčovým ministerstvům konzultace o možných rizicích i o modelech řešení. Jako ukázku vzájemné důvěry lze uvést, že část výzbroje, připadající Slovensku, zůstala na českém území i po rozdělení státu, do doby, dokud Slovensko nevybudovalo prostory pro její umístění. Rozdělení Československa bylo v zahraničí považováno spíše za negativum, ale s odstupem lze konstatovat, že kultivovaný způsob česko-slovenského rozdělení nakonec přispěl k prestiži obou nových států.

criticisms http://www.mzv.cz/wwwo/mzv/default.asp?id=29786&ido=7970&idj=1&amb=1

The Breakup of Czechoslovakia Velvet revolution

Forced by the popular movement (and by changes in Soviet policy towards Central European Allies) the Communist Party dropped its claims to "a leading role" in November and December 1989. President Husak was replaced by Vaclav Havel, playwright and dissident, who led the strongest political organisation of that era, Civic Forum (CF). An allied (formally independent) organisation Public Against Violence (PAV) was founded in Slovakia. Negotiations between renewed leadership of Communist Party and the alliance of non-communist organisations led by CF and PAV yielded new Government led by a Slovak communist, M. Calfa who soon deserted to PAV. The Federal Assembly was reconstructed. The most outspoken representatives of the old regime were ousted and replaced by those of new political organisations. The system of central planning was abandoned. The country has been striving to reintroduce market economy and to forge close links with the international economic and financial community.

A serious Czecho-Slovak conflict suddenly emerged when the Federal Assembly discussed the proposal to drop the attribute "socialistic" (introduced by A. Novotny in 1960) out of the name of the country. Many Slovak deputies demanded that the country return to its original name Czecho-Slovakia, adopted by the Treaty of Versailles in 1918. (The hyphen has been dropped out only in 1923). After unexpectedly fierce discussions the country was renamed as Czech and Slovak Federal Republic in April 1990. At the same time Slovak National Party (demanding the independence of Slovakia) was founded.

The first free elections for 40 years were held in June 1990. Jan Carnogursky, the leader of Slovak Christian Democratic Movement (CDM) protested against President Havel's "intervening in Slovak internal affairs" and his open agitation for the PAV. CF won absolute majority in the Czech Republic and formed a single party government there. On the other hand PAV had to form a coalition with CDM. The federal government was formed by members of CF, PAV and CDM. Both governments, federal and Slovak, were led by PAV - members (Calfa and V.Meciar). Nevertheless, strong jurisdictional disputes soon emerged between these two governments causing serious political crises in the PAV as well as in the whole federal state. After some hesitation CDM joined the pro-federal wing of PAV. They, together with two Hungarian parties, managed to establish a very slight majority in the Slovak National Council and in its Presidium, that ousted Meciar and replaced him by J. Carnogursky in April, 1991. Meciar's group split from the PAV and established so-called Movement for Democratic Slovakia (HZDS). The Civic Forum had split even earlier. Its major part formed the Civic Democratic Party (CDP) led by pragmatic Finance Minister V. Klaus. Many prominent former dissidents found themselves isolated in a small Civic Movement that failed to gain any of the seats in the Federal or Czech Parliament in the next elections in 1992.

Under the overwhelming influence of V. Klaus the crude form of monetarism that had been hardly practised elsewhere, has dominated economic policy. Already suffering from external shocks - collapse of the market for Czechoslovak goods in the Soviet Union and other former East block countries - the country has been subjected to macro-economic policies assuring a collapse of domestic demand as well. The real volume of credits was decreased by 30% and the real wages declined by 26,9% in the first half of 1991 while the personal consumption dropped by 37%. As a result industrial production was down by about one-third in 1991. Unemployment, virtually non-existent before 1990, rise to 8,4% in April 1992 (12,7% in Slovakia). Such a rates of decline make the Great Depression of 1930s pale.

The government's approach to privatisation and its methods (e.g. voucher privatisation, physical restitution, non-competitive sale to a predetermined owner, sale to foreign entity, "Dutch auctions", uncompensated transfer to commercial banks) have provoked controversial discussions both in the country and abroad.

Discussions on the future constitution of the country and related negotiations did not yield the desired effect. Their only remarkable indirect result was splitting of CDH to a national wing - the Slovak CDH(SCDH)— and pro-federal wing (CDH). Velvet Divorce

The results of the elections of June 1992 reflected the growing split between the two lands. The liberal Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS), led by Slovak Vladmir Meciar, and the conservative Civic Democratic Party, led by Czech Vclav Klaus won the two largest representations in parliament; each leader became the prime minister of his own republic. Disagreements between the republics intensified, and it became clear that no form of federal government could satisfy both.

Both of them gained more than one third of seats within their republics where they can easily form coalitions with sympathising parties. CDS ran for election in Slovakia as well but it failed to reach 5% threshold. This "schizophrenic" election result led a series of negotiations between two victorious parties. They agreed to form a federal government on the principle of symmetric power-sharing. However, this government had only a limited mandate until the end of 1992. CDS considered the principle of symmetry claimed by HZDS as impractical and unprofitable. (There are approximately 10 millions of Czechs and 5 millions of Slovaks.) CDS also refused the proposal of Slovak partners to transform the country into a loose federation based on the principle of the Treaty of Maastricht and Premier Klaus uttered pessimistic comments concerning that treaty. This principal dis-consensus yielded the conditions necessary for negotiations for breakup.

In July 1992 Slovakia declared itself a sovereign state, meaning that its laws took precedence over those of the federal government. Throughout the fall of that year, Meciar and Klaus negotiated the details for disbanding the federation. In November the federal parliament voted to dissolve the country officially on December 31, despite polls indicating that the majority of citizens opposed the split. In January 1993 Czechoslovakia was replaced by two independent states: Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Slovaks gathered for celebrations in their new nation’s capital at Bratislava. Independence under Meciar’s leadership, the process of privatization slowed in Slovakia. However, a divorce can hardly be pleasant, especially because of usual problems connected with splitting of common assets. One of the main problems that remained to be settled is the division of the pipeline that transports Russian gas to Germany. No better solution has been find than the construction of an extra pumping station at the new common border. On the other hand, especially for Slovakia, this pipeline is one of the most important factors of countries strategic position. It crosses 8 times the border line between Slovakia and Hungary from the period 1939-45. This is therefore a very strong argument for the stability of the present border between these two countries.

In February 1993 Michal Kovac was elected president of the country. Although a fellow member of the HZDS party, Kovac was not a Meciar ally, and conflicts soon developed within the government. Meciar’s position was further undermined by the resignation and defection of a number of party deputies in early 1994. In March of that year, Meciar resigned from office after receiving a vote of no confidence from the Slovak parliament. An interim coalition government comprising representatives from a broad range of parties was sworn in, with Jozef Moravcik of the Democratic Union of Slovakia Party as prime minister. Moravcik’s government revived the privatization process and took steps to attract more foreign investment to Slovakia. It also helped to calm the increasingly strained relations between Slovaks and resident Hungarians, who had begun campaigning for educational and cultural autonomy. In May a law was passed by parliament allowing ethnic Hungarians in Slovakia to register their names in their original form; this replaced previous legislation requiring Hungarians to convert their names to the Slavic form.

* Topics in Slovak History: * Hungarian Ethn

http://www.slovakia.org/history-breakup.htm

Administrative Division

- 1918–1927: comprised three lands — former Austrian territory of Bohemia, Moravia, and a small part of Silesia), and former Hungarian territory of Slovakia and Ruthenia divided into districts

- 1928–1938: four lands — Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia, and Subcarpathian Ruthenia divided into districts

- late 1938–March 1939 — Slovakia and Ruthenia became autonomous lands

- 1945–1948 — Ruthenia became part of the Soviet Union

- 1949–1992 — Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic established in 1969 (both dropped the word Socialist in 1990)

Economy

http://www.mfcr.cz/cps/rde/xchg/mfcr/hs.xsl/historie_min.html

Období první republiky 1918 - 1938

I. Vznik Československa a snaha o stabilizaci veřejných rozpočtů a měny (1918 - 1925)

II. Léta konjunktury (1926 - 1929)

III. Velká hospodářská krize (1930 - 1934)

IV. Za zachování národní svébytnosti (1935 - 1938)

V. Daňová a celní správa v období první republiky

I. Období druhé republiky (1938 - 1939)

II. Protektorát Čechy a Morava (1939 - 1945) III. Státní zřízení v exilu (1939 - 1945) IV. Léta omezené demokracie (1945 - 1948)

I. Nástup totalitního systému, jeho upevnění a krize (1948 - 1968)

II. Léta "reálného socialismu" (1968 - 1989)

III. Řešení následků druhé světové války (válečné reparace, měnové zlato) a problematiky náhrad za poválečné znárodnění

IV. Daňová a celní správa v období totality

Fotogalerie

I. Společenská a ekonomická transformace, vznik České republiky a její vstup do Evropské unie

II. Daňová a celní správa po roce 1989

Vznik Československa a snaha o stabilizaci veřejných rozpočtů a měny (1918 – 1925) Rok 1918 představoval již čtvrtý rok krutého válečného konfliktu, který se rozšířil do celého světa. Během léta se začalo jasně ukazovat, že Centrální mocnosti zastoupené Německem, Rakousko-Uherskem, Tureckem a Bulharskem již dlouho nevydrží odolávat intenzivnímu tlaku dohodových vojsk na všech frontách. V případě Rakouska-Uherska se problémy objevovaly jak na frontě, tak i v zázemí a vyústily v úplné rozklížení tohoto staletého soustátí. Výsledkem byl celkový rozpad habsburské monarchie na několik tzv. nástupnických států, mezi které patřilo i Československo. Oficiální vznik nového státu střední Evropy je datován na 28. října 1918, kdy byl veřejně vyhlášen zákon o zřízení samostatného státu československého (zákon č. 11/1918 Sb. z. a n.). Prvotním vykonavatelem státní svrchovanosti se stal Národní výbor československý. Aby byla zachována kontinuita s dosavadním právním řádem, nařídil jménem československého národa mimo jiné, že veškeré dosavadní zemské a říšské zákony a nařízení zůstávají prozatím v platnosti a všechny úřady samosprávné, státní a župní, ústavy státní, zemské, okresní a zejména i obecní jsou podřízeny Národnímu výboru a prozatím úřadují a jednají dle dosavadních platných zákonů a nařízení (tzv. zákon recepční). Provedení zákona bylo současně uloženo Národnímu výboru. Zákon podepsali Alois Rašín, Antonín Švehla, František Soukup, Jiří Stříbrný a Vavro Šrobár.1

Bouřlivé desetiletí (1938 - 1948)

I. Období druhé republiky (1938 – 1939)

Období druhé československé republiky vymezené mnichovskou dohodou, uzavřenou 30. září 1938, a okupací českých zemi nacistickým Německem 15. března 1939, představovalo viděno historickým odstupem období ryze přechodné, poznamenané především nutnosti vyrovnat se s politickými a hospodářskými dopady ztráty pohraničních území. Rovněž s sebou přineslo zásadní obrat od konceptu státu liberálně demokratického ke státu autoritativně-nacionalistickému. Krátká časová existence, navíc v bouřlivém období těsně předválečné Evropy, znamenala pro fungování státu především improvizaci a tápání spolu s absencí resp. nemožností realizace dlouhodobých zákonodárných a správních aktivit. Po stránce hospodářské bylo nutné řešit především okamžité hospodářské důsledky Mnichova, přičemž byl patrný jistý posun od liberální tržní ekonomiky směrem k direktivnímu hospodářství.

Reakcí značné části společnosti a politických kruhů na mnichovskou katastrofu se stal všeobecný nárůst nacionalismu a antisemitismu, přičemž vina za Mnichov byla připsána zejména předchozímu systému masarykovské demokracie a pluralitního stranictví. Vnitřní politika se tedy nesla ve znamení „zjednodušení“, směřujícího k vytvoření systému dvou stran (pravicové vládnoucí Strany národní jednoty a levicové „loajálně“ opoziční Národní strany práce). Zároveň postupně docházelo k zásahům a omezování těch společenských a politických aktivit, které byly spjaty s první republikou či se jakkoliv neidentifikovaly s nově budovaným režimem. Nemalým vlivem zde působil tlak nacistického Německa, jehož „vazalem“ se druhá republika velmi rychle stávala. Na Slovensku pak postupně politickou scénu opanovalo klerofašistické luďácké hnutí. Zároveň se však velká část obyvatelstva českých zemí s novými poměry neztotožnila, považovala druhou republiku za dočasný stav a chovala naděje na budoucí obnovení státu v předmnichovských hranicích a v masarykovském duchu.

Odstoupení pohraničních území Německu a současné odstoupení Těšínska Polsku znamenalo ztrátu přibližně 38 % státního území (cca 30 000 km2) a 36 % obyvatelstva (cca 3,86 mil obyvatel).1 Další ztráty přinesla tzv. vídeňská arbitráž znamenající odstoupení jižních oblastí Slovenska a Podkarpatské Rusi Maďarsku. Velkou ranou byla ztráta pohraničí především pro československé hospodářství, neboť' došlo k zpřetrhání staletých ekonomických vazeb v české kotlině, ke ztrátě značné části surovinových zdrojů a průmyslové základny. Cíleně byla narušena dopravní síť. Dalším negativním důsledkem byl pokles zahraničního obchodu. Dlouhodobým a naléhavým ekonomickým problémem se konečně stal příliv českých uprchlíků z pohraničí, který dramaticky zvyšoval míru nezaměstnanosti a konkurenční tlaky v drobném podnikání. Větší část uprchlíků navíc tvořili státní zaměstnanci, pro které nebylo na zmenšeném území vhodné využití.

III. Státní zřízení v exilu (1939 – 1945)

Paralelně s existencí Protektorátu Čechy a Morava se v západním exilu, především ve Velké Británii, zformovalo prozatímní státní zřízení, usilující o poválečnou obnovu Československa, a to v jeho předmnichovských hranicích. Základní politicko-právní východiska při tom byla následující.

Samostatné Československo nikdy právně nezaniklo, neboť okupace českých zemí 15. března 1939 byla zjevným porušením mezinárodního práva a konec konců i Mnichovské dohody. V tomto směru byla situace československého exilu relativně jednoduchá, neboť západní velmoci okupaci českých zemí nikdy oficiálně neuznaly, ačkoliv jejich politika byla až do vypuknutí války obojaká a směřují cí k uznání okupace de facto. Problémem ovšem byla otázka Slovenského státu, který některými státy uznán byl.

III. Státní zřízení v exilu (1939 – 1945) Paralelně s existencí Protektorátu Čechy a Morava se v západním exilu, především ve Velké Británii, zformovalo prozatímní státní zřízení, usilující o poválečnou obnovu Československa, a to v jeho předmnichovských hranicích. Základní politicko-právní východiska při tom byla následující.

Samostatné Československo nikdy právně nezaniklo, neboť okupace českých zemí 15. března 1939 byla zjevným porušením mezinárodního práva a konec konců i Mnichovské dohody. V tomto směru byla situace československého exilu relativně jednoduchá, neboť západní velmoci okupaci českých zemí nikdy oficiálně neuznaly, ačkoliv jejich politika byla až do vypuknutí války obojaká a směřují cí k uznání okupace de facto. Problémem ovšem byla otázka Slovenského státu, který některými státy uznán byl. IV. Léta omezené demokracie (1945 – 1948) Období let 1945 až 1948 tvoří v dějinách Československa další klíčový zlom, jehož hodnocení nemůže být jiné než rozporuplné. Na jedné straně spolu s konce války došlo k obnovení Československa v jeho předmnichovských hranicích (s výjimkou Podkarpatské Rusi) a tedy k naplnění primárního cíle domácího i zahraničního odboje. Na druhé straně se však země musela vyrovnávat s lidskými a materiálními ztrátami, které válka způsobila, i s dalšími obrovskými změnami jako byl např. odsun Němců. Především se však už jednalo o “jiné” Československo, než byla masarykovská první republika. Polodemokratický systém Národní fronty, prakticky nepřipouštějící vznik opozice stojící mimo ni, vedl především k likvidaci před válkou nejsilnější agrární strany, jejíž místo rychle obsadili komunisté. Léta 1945 – 1948 tak byla vyplněna neustálými potyčkami ve vládě i mimo ni mezi komunisty a ostatními stranami. Nedílnou součástí doby byly poměrně zásadní hospodářské reformy, především v podobě první vlny znárodnění. O těchto změnách sice panoval mezi vládními stranami v zásadě konsenzus, avšak ve svých důsledcích přirozeně nahrávaly Komunistické straně. Demokratické síly se tak dostávaly do jejího vleku, který byl podpořen infiltrací ostatních stran prokomunistickými elementy. Již od odmítnutí Marshallova plánu v roce 1947 začalo být stále více zjevné, že těsně poválečná léta budou jen krátkým nadechnutím před nástupem druhé totality. Tzv. Marschallův plán představoval masivní hospodářskou pomoc Spojených států válkou zdevastované Evropě, kde měl přispět k znovuvybudování zničeného a na válečnou výrobu přeorientovaného průmyslu. S odstupem času je obecně hodnocen jako základní příčina poválečného hospodářského rozmachu Západní Evropy (a to včetně pozdější SRN). Československo bylo spolu s Polskem přímým rozkazem Stalina donuceno zahraniční pomoc ze Západu odmítnout, což jej definitivně odeslalo do sovětské sféry vlivu. Základem bezprostředně poválečného zákonodárství byly opět dekrety prezidenta republiky Edvarda Beneše, v jejichž vydávání pokračoval na základě dekretu č. 3/1945 Úředního věstníku čsl., o výkonu moci zákonodárné v přechodném období, a to až do ustavení Národního shromáždění. Tak bylo vydáno značné množství dekretů upravujících poválečnou obnovu Československa a zahrnujících první politické a hospodářské reformy, přičemž řada z nich byla vydána ještě před koncem války na přelomu let 1944 a 1945. Po právní stránce byl klíčovým dekret č. 11/1945 Úředního věstníku

II. Léta „reálného“ socialismu (1968 – 1989)

Po jednáních v Moskvě se uvěznění českoslovenští reformističtí představitelé podrobili sovětskému nátlaku a akceptovali okupaci. Přes řadu protestních akcí (upálení Jana Palacha na Václavském náměstí, tzv. Hokejový týden) byly v průběhu let 1969 až 1970 negovány veškeré výsledky reforem, včetně osobní eliminace reformních politiků. Klíčové pozice ve státě obsadili prosovětští kolaboranti, kteří zahájili období tzv. normalizace. Do čela strany a posléze i státu se dostal symbol ideově i hospodářsky sterilního „reálného“ socialismu 70. a 80 let., Gustáv Husák. Normalizace přinesla další rozsáhlou perzekuci obyvatelstva, která ovšem měla charakter spíše společensko – hospodářský než trestní. Rovněž následovala další rozsáhlá vlna emigrace na Západ.

Odrazem vývoje politických událostí byla i situace na Ministerstvu financí. Původní nadšení pro reformy postupně mizelo v rámci prověrek, jimž byli podrobeni straníci i nestraníci na všech úrovních funkcí. Řada pracovníků byla vyloučena ze strany, mnoho zaměstnanců muselo Ministerstvo opustit. Tato situace a stálá nejistota měla negativní vliv na hodnotu práce na Ministerstvu. Ministr Sucharda podle pamětníků nepatřil k příznivcům vojenského vpádu. V prvních dnech po vstupu sovětských vojsk a obsazení Úřadu vlády se údajně konala noční schůze vlády utajeně na Ministerstvu financí. Sovětská vojska konala prohlídky na Ministerstvu ve dne i v noci a tyto prohlídky odůvodňovala tím, že hledala zbraně. Kontrolováni byli i pracovníci Ministerstva přicházející do úřadu.

V říjnu 1968 došlo k zásadní státoprávní změně přijetím zákon o československé federaci. Od 1. 1. 1969 tak vznikla tři Ministerstva financí: federální, české a slovenské. Federálním ministrem financí zůstal až do 27. 9. 1969 Bohumil Sucharda v rámci druhé Černíkovy vlády (1. 1. 1969 – 27. 9. 1969). Rovněž následující vládu od 27. 9. 1969 vedl O. Černík, nahrazený však již 28. 1. 1970 Lubomírem Štrougalem, stojícím v čele vlády až do 9. 12. 1971. Ministrem financí v této vládě se stal Rudolf Rohlíček. V následující druhé Štrougalově vládě (9. 12. 1971 - 11. 11. 1976) na postu ministra financí ke změně zprvu nedošlo, avšak 14. 12. 1973 se novým ministrem stal Leopold Lér. Ten pak zůstal ve funkci i ve třetí Štrougalově vládě (11. 11. 1976 - 17. 6. 1981). Ve čtvrté (17. 6. 1981 - 16. 6. 1986) jej pak od 29. 11. 1985 nahradil Jaromír Žák, který státní finance spravoval i ve Štrougalově vládě páté a šesté (16. 6. 1986 - 20. 4. 1988 a 21. 4. 1988 - 12. 10. 1988). V poslední komunistické vládě za předsednictví Ladislava Adamce (12. 10. 1988 - 10. 12. 1989) byl ministrem Jan Stejskal.

I. Společenská a ekonomická transformace, vznik České republiky a její vstup do Evropské unie Záhy po Listopadu 1989 byl název státu změněn na Česká a Slovenská Federativní republika (ČSFR). V roce 1990 až 1991 konečně opustila republiku sovětská vojska a zanechala po sobě značné dluhy a zpustošené domy ve vojenských újezdech. Současně byla zrušena Varšavská smlouva. Československo rovněž odvolalo svoji účast v RVHP. Později vláda České republiky svým usnesením ze dne 2. června 1993 č. 291 stanovila postup při jednání o majetkoprávních nárocích České republiky k majetku Rady. Následovala její majetková likvidace.

After WWII, economy centrally planned with command links controlled by communist party, similar to Soviet Union. Large metallurgical industry but dependent on imports for iron and nonferrous ores.

- Industry: Extractive and manufacturing industries dominated sector. Major branches included machinery, chemicals, food processing, metallurgy, and textiles. Industry wasteful of energy, materials, and labor and slow to upgrade technology, but country source of high-quality machinery and arms for other communist countries.

- Agriculture: Minor sector but supplied bulk of food needs. Dependent on large imports of grains (mainly for livestock feed) in years of adverse weather. Meat production constrained by shortage of feed, but high per capita consumption of meat.

- Foreign Trade: Exports estimated at US$17.8 billion in 1985, of which 55 % machinery, 14 % fuels and materials, 16 % manufactured consumer goods. Imports at estimated US$17.9 billion in 1985, of which 41 % fuels and materials, 33 % machinery, 12 % agricultural and forestry products other. In 1986, about 80 % of foreign trade with communist countries.

- Exchange Rate: Official, or commercial, rate Kcs 5.4 per US$1 in 1987; tourist, or noncommercial, rate Kcs 10.5 per US$1. Neither rate reflected purchasing power. The exchange rate on the black market was around Kcs 30 per US$1, and this rate became the official one once the currency became convertible in the early 1990s.

- Fiscal Year: Calendar year.

- Fiscal Policy: State almost exclusive owner of means of production. Revenues from state enterprises primary source of revenues followed by turnover tax. Large budget expenditures on social programs, subsidies, and investments. Budget usually balanced or small surplus.

After WWII, country energy short, relying on imported crude oil and natural gas from Soviet Union, domestic brown coal, and nuclear and hydroelectric energy. Energy constraints a major factor in 1980s.

Demographics

Czechoslovakia's ethnic composition in 1987 was in a stark contrast to its pre-WWII state. The Sudeten Germans that made up the majority of the population in border regions had been forcibly expelled and Ruthenia had been ceded to the Soviet Union following World War II. Czechs and Slovaks, who represented two-thirds of the population in 1930, accounted for 94% by 1950.

While the aspirations of ethnic minorities had been the pivot of the First Republic's politics, they were no longer the case in the 1980s. Nevertheless, ethnicity continued to be a sensitive issue due to the distinct historical experiences and divergent aspirations of Czechs and Slovaks. From 1950 through 1983, the Slovak share of the total population increased steadily as the Czech portion declined by 4%. In 1983 the Czech-Slovak ratio equalled 2:1, but in the mid-1980s, Slovaks almost closed the gap in the number of births.

From Creation to Dissolution — Overview

|

Czechoslovakia (or Czecho-Slovakia) | 1918 - 1939; 1945 - 1992 |

|||||||

|

Austria-Hungary (Bohemia, Moravia, a part of Silesia, northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia) |

Czechoslovak Republic |

Sudetenland + other German territories "Upper Hungary" territories of Hungary |

Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) |

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) |

Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (ČSFR) |

Czech Republic Slovakia |

|

|

Czecho-Slovak Republic (ČSR) incl. autonomous Slovakia and Transcarpathian Ukraine (1938-1939) |

Protectorate WWII Slovak Republic |

||||||

|

(further) "Upper Hungary" of Hungary |

part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic |

Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine |

|||||

|

German occupation |

Communist era |

||||||

|

govern. in exile |

|||||||

Footnotes

- ↑ Playing the blame game, Prague Post, July 6th, 2005

- ↑ http://zpravy.idnes.cz/chcete-znicit-prahu-ptal-se-goring-hachy-f0x-/domaci.asp?c=A070315_093114_domaci_adb

- ↑ http://zpravy.idnes.cz/chcete-znicit-prahu-ptal-se-goring-hachy-f0x-/domaci.asp?c=A070315_093114_domaci_adb

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich_Agreement

- ↑ http://www.law.nyu.edu/eecr/vol11num1_2/special/rupnik.html

External Links

English Language

- Czechoslovak Republicdefunct link, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- "Munich Agreement" Wikipedia, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- "Velvet Revolution"] Wikipedia, Retrieved June 14, 2007.

Czech Language

- “Czechoslovak Orders and Medals” Awards, Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- “Lidice a Ležáky“ Czech Republic History, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Gazdik, Jan March 15, 2007 ”Do You Want to Destroy Prague? Goring Asked Hacha” iDnes News, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Czechoslovak Resistance Movement in the West” Wars, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Emergence of Czechoslovakia and Shaping of our Borders” Jan Skokan’s History Website, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Mikulecky, Tomas “Emergence of Czechoslovakia” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement, the Role of the Three Kings and the Resistance Movement Role of Vladimir Krajina” History, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ”Life in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Assassination of Reynhard Heidrich” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Velvet Revolution or Eleven Days that Rocked Czechoslovakia” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.* “International Events of 1989” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Political Processes in the Czech Socialist Republic 1948-1989” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Timeline of November 17 Demonstrations” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Charter 77” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Velvet Revolution ‘89” 1989 Revolution, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.