Difference between revisions of "Czechoslovakia" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

===1989 in the World=== | ===1989 in the World=== | ||

| − | + | Mikhail Gorbatchev’s address to the [[United Nations]] General Assembly in [[New York]], in which he endorsed the rights for all nations to shape their destiny, was among the first signs of the worldwide crumbling of the Communist empire. Gorbatchev followed through with a unilateral withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops from Europe and [[Asia]] and rehabilitated victims of [[Stalin]]'s rule. Elections in March 1989 saw Communist candidates defeated, which spurred calls for the secession of the small Soviet republics from the Soviet Union. [[Hungary]] started taking steps toward democracy by allowing other than Commmunist political parties, but Communist authorities in Prague brutally dispersed ad hoc anti-regime demonstrations and [[Romania]] imprisoned journalists brave enough to criticize its President [[Ceausescu]]. Bloodbath occurred at East [[Berlin]]'s infamous Berlin Wall. In [[Poland]], a series of strikes forced the government to forge a deal with Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarita movement. One million students in [[Beijing]] took to the streets hoping that Gorbachev’s visit to [[China]] would be followed by reforms; however, thousands of them were massacred at the Tchien-an-men Square. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===November 1989=== | ===November 1989=== | ||

| − | The demonstrations were planned for November 17 in commemoration of the November 17, 1939, Nazi attack against university dormitories in Czechoslovakia and the subsequent closure of universities for three years. In 1989, however, it was not only water hoses and spontaneous arrests but also sheer violence used against young people, which set in motion the events that unseated Communism in the country. The main protagonists of the Velvet Revolution were students in | + | The demonstrations were planned for November 17 in commemoration of the November 17, 1939, Nazi attack against university dormitories in Czechoslovakia and the subsequent closure of universities for three years. In 1989, however, it was not only water hoses and spontaneous arrests but also sheer violence used against young people, which set in motion the events that unseated Communism in the country. The main protagonists of the Velvet Revolution were Prague students in , who solicited support of actors, lead by Vaclav Havel, Alexander Dubcek, |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==After 1989== | ==After 1989== | ||

Revision as of 02:52, 14 June 2007

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

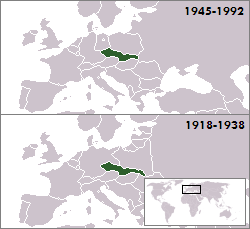

Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak: Československo, or (increasingly after 1990) in Slovak Česko-Slovensko) was a country in Central Europe that existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992 (with a government-in-exile during the World War II period). On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia peacefully split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. After WWII, active participant in Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), Warsaw Pact, United Nations and its specialized agencies; signatory of conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

After WWII, monopoly on politics held by Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Gustáv Husák elected first secretary of KSC in 1969 (changed to general secretary in 1971) and president of Czechoslovakia in 1975. Other parties and organizations existed but functioned in subordinate roles to KSC. All political parties, as well as numerous mass organizations, grouped under umbrella of the National Front.

Basic Facts

Form of statehood:

- 1918–1938: democratic republic

- 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by Germany in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, Slovak and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by Hungary, while the Zaolzie region went under Poland's control

- 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the independent Slovakia, although Czechoslovakia was never officially dissolved; its exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, was based in London. Following the German invasion of Russia, the Soviet Union recognized the exiled government as well.

- 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with Communist ministers charting the course

- 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy

- 1960 on: the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

- 1969–1990: a federal republic consisting of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic

- 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic

Official Names

- 1918–1920: Czecho-Slovak Republic or Czechoslovak Republic (abbreviated RČS); short form Czecho-Slovakia or Czechoslovakia

- 1920–1938 and 1945–1960: Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR); short form Czechoslovakia

- 1938–1939: Czecho-Slovak Republic; Czecho-Slovakia

- 1960–1990: Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR); Czechoslovakia

- April 1990: Czechoslovak Federative Republic (Czech version) and Czecho-Slovak Federative Republic (Slovak version),

- afterwards: Czech and Slovak Federative Republic (ČSFR, with the short forms Československo in Czech and Česko-Slovensko in Slovak)

History

Inception

Czechoslovakia came into existence in October 1918 as one of the successor states of Austria-Hungary following the end of World War I. It comprised the territory of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia and some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. On October 16, 1918, Emperor Charles I attempted to rescue the crumbling Habsburg Monarchy by proposing a federal monarchy, but two days later, US President Woodrow Wilson in January 1918 issued Fourteen Points, proclaiming an independent state of Czechs and Slovaks. The document was drawn up by Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, who united Czechs and Slovaks living abroad around the common goal of a joint state and was the driving force behind the Czechoslovak resistance movement based outside the country. It was addressed to Wilson and the US Government in response to the foreign policy of Emperor Charles I – Czechs and Slovaks were not satisfied with an “autonomy” within the Habsburg Monarchy but pursued complete independence. The proclamation was a blueprint for the constitution of the state-in-the-works, vowing broad democratic rights and freedoms, separation of state from Church, expropriation of land, and abolishment of the class system.

On October 28, 1918, Alois Rašín, Antonín Švehla, František Soukup, Jiří Stříbrný, and Vavro Šrobár, known as the "Men of October 28th", formed a provisional government, and two days later, Slovakia endorsed the marriage of the two countries, with Masaryk elected president.

World War II

End of State

Satisfaction among individual ethnic groups within the new state varied, as Germans, Slovaks, and Slovakia's ethnic Hungarians grew resentful of the political and economic dominance of the Czechs. These ethnic groups, as well as Ruthenians and Poles, felt disadvantaged in a centralized state that was reluctant to safeguard political autonomy for all of its constituents. This policy, combined with an increasing Nazi propaganda, particularly in the industrialized German speaking Sudetenland (the German-border regions of Bohemia and Moravia) and its calls for the creation of a new province, Deutschösterreich (German Austria) and later Deutschböhmen (German Bohemia), fueled the growing unrest in the years leading up to World War II.[1]) Many Sudeten Germans rejected affiliation with Czechoslovakia because their right to self-determination coined in the Fourteen Points had not been honored.

Following the German annexation of Austria, referred to as the Anschluss, the Sudetenland would be Adolf Hitler's next demand. The Munich Agreement, signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Hitler, Great Britain—Neville Chamberlain, Italy—Benito Mussolini, and France—Édouard Daladier, robbed Czechoslovakia of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, where most of the country's border defences were situated. Wehrmacht troops occupied the Sudetenland in October 1938. Within ten days, 1,200,000 Czechs and Slovaks living there were told to leave their homes, and the severely weakened Czechoslovak Republic was forced to grant major concessions to the non-Czechs.Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and Emil Hácha, a highly respected lawyer by training and independent thinker, was appointed president. Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without taking up. In November, the First Vienna Award handed over part of southern Slovakia to Hungary.

On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Hitler; the same day, Slovakia declared independence and became an ally of Nazi Germany, which provided Hitler with a pretext to occupy Bohemia and Moravia on grounds that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within and his administration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia would forestall chaos in Central Europe. Hácha described the signing away of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany, for which he had been traditionally labeled as national traitor, as follows: “It’s possible to withstand Hitler’s yelling, because a person who yells is not necessarily a devil. But Göring [Hitler’s right hand], with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful Prauge to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, capable of carrying out his threat, was speaking to me.” [2] Göring further asked Hácha: “You do not want or cannot understand the Führer, who wishes that lives of thousands of Czech people are spared?” [3]

The president had been subjected to enormous psychological pressure in the course of which he collapsed repeatedly. The next morning, Wehrmacht occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that “We would have shed a lot of blood.” [4] Czechoslovakia’s factories thus began churning out equipment for the Third Reich.

Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an anti-government uprising that was quickly crushed by Germany.

Resistance Movement

On October 28, 1939, the 21st anniversary of the establishment of the country, Czechoslovakia, emboldened by hopes for an early restoration of the independence, was swept by massive demonstrations. Medical student Jan Opletal was killed in Prague in confrontations with the occupants, which spurred further unrest that provoked Nazi terror targeting students, spontaneous executions of student leaders, and the closure of universities. These reprisals signaled that continued open encounter with the occupation forces was not feasible; therefore, resistance movement shifted to underground organizations and networks. The goal of the London-based exiled government, headed by Edvard Beneš, in conjunction with efforts of national and foreign-based Czechoslovak representative offices, was to restore the independent Czechoslovakia. The government oversaw formation of Czechoslovak units in Poland, France and Great Britain composed of recruits from the ranks of exiled Czechoslovak citizens.

On the home turf, resistance movement continued chiefly through massive demonstrations, which reached an apex in 1941. The society was split in three streams with respect to their stance on the Nazi occupation: the largest chunk of the population comprised people who passively rejected the occupation and would swing both ways. Then there were those who supported the resistance movement, and, lastly, resistance movement groups and organizations seeking the restoration of the independent Czechoslovak Republic. However, widespread arrests severely disrupted the underground networks and cut off radio networks between domestic and foreign components of the resistance movement, which were then reestablished by paratroopers dispatched into the Protectorate.

Operation Anthropoid

The Czechoslovak-British Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination of the top Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich, the chief of RSHA, an organization that included the Gestapo (Secret Police), SD (Security Agency) and Kripo (Criminal Police). Heydrich was the mastermind of the purge of Hitler's opponents as well as the genocide of Jews. Being a valued political ally, advisor and friend of the dictator, he had his hands in most of Hitler's intrigues and was feared by Nazi generals. Thanks to his reputation as the liquidator of resistance movements in Europe, he was sent to Prague in September 1941 as the Protector of Bohemia and Moravia to make order. The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was of strategic importantance to Hitler’s plans, and Heydrich, dubbed the “Butcher of Prague”, "The Blond Beast" or "The Hangman", wasted no time upon his arrival, handing out death sentences for Czech military officials, resistance movement fighters and political figures the day after his arrival in Prague.

With the fighting spirit in the Protectorate at lull, the exiled military officials started planning an act that would stir up the nation’s consciousness — six Czech and one Slovak paratroopers were chosen for the assassination of Heydrich, and two of them— Czech Josef Valčík and Slovak Josef Gabčik, carried out the act. Heydrich died of complications following surgery. The Gestapo tracked the paratroopers’ contacts and eventually discovered the paratroopers’ hideaway in a Prague church. Three of them died in a shootout, trying to buy time for the others so that they could dig out an escape route. The Gestapo found out and used tear gas and water to chase the remaining four out, who used their last bullets to take their lives rather than fall in the Nazi hands alive.

Heydrich’s successor Karl Herrmann Frank had 10,000 Czechs executed as a warning, and two villages that assisted the paratroopers were leveled down, with the adults executed and young children sent to German families for re-education. The combined actions of the Gestapo and its confidantes virtually paralyzed the Czech resistance movement; on the other hand, the assassination bolstered Czechoslovakia’s prestige in the world and was crucial to the country’s securing of demands for an independent republic following the end of WWII.

End of War

Toward the end of the war, partisan movement was gaining momentum, and once the Allies were on the winning side, the political orientation of Czechoslovakia was high on the agenda of the two most influential exiled centres–the government in London and the communist officials in Moscow. Both saw the agreement on friendship, mutual assistance and postwar cooperation between Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union as a means to stem German expansion and the Soviet Union’s mingling into Czechoslovakia's internal affairs. The country was liberated by the Soviet Union's Red Army and partly by the US Army on May 9.

Communist Czechoslovakia

Communist Takeover

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reestablished. Carpathian Ruthenia has been occupied by and in June 1945 formally ceded to the Soviet Union, while ethnic Germans inhabiting the Sudetenland were expelled in an act of retaliation coined by the Beneš Decrees. Wartime "traitors" and collaborators accused of treason along with ethnic Germans and Hungarians were expropriated, with those ethnic Germans and Hungarians who switched to German and Hungarian citizenship during the occupation stripped of their national identity. These provisions were lifted for the Hungarians in 1948. Altogether around 90% of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia was made leave. Although the decrees specified that the sanctions did not apply to anti-fascists, the decisions were up to local municipalities. Some 250,000 Germans, many married to Czechs and anti-fascists, remained. The Beneš Decrees continue to fuel controversy between nationalist groups in the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, and Hungary. [5].

The Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia was facilitated by the liberation of most of the country by the Red Army and by the overall social and economic downturn in Europe. Marshall’s Plan, authored by US State Secretary George Marshall in June 1947, addressed the European needs with an offer of financial and material aid and thus stabilization of the region but was turned down by the Soviet Union and, consequently, by its satellites, including Czechoslovakia. In the 1946 parliamentary election, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia emerged as the winner in the Czech lands while the Democratic Party won in Slovakia, and in February 1948, the Communists seized power and sealed the country’s fate for the next 41 years. Terror reminiscent of Hitler’s Germany followed, with execution of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, forceful collectivization of agricutlrue, censorship, and land grabs. Economy was controlled by five-year plans and the industry was overhauled in compliance with Soviet wishes to focus on heavy industry, in which Czechoslovakia had been traditionally weak. The economy retained momentum vis-à-vis its Eastern European neighbors but grew increasingly weak vis-a-vis Western Europe. Atheism became the official spiritual doctrine.

Year 1960 saw the declaration of the victory of socialism, with small businesses stamped out and the country’s name changed to the Czechoslovak Soicialist Republic. In early 60s, the socialist planning brought about an economic crisis and reshuffles in the Communist leadership. Economic reforms were put in place that grew into the reform of the overall political system. Slovakia’s Alexander Dubček took over with the doctrine of ‘socialism with human face, called the Prague Spring, but these efforts were crushed under the tanks of the Warsaw Pact armies on August 21, 1968.

Prague Spring was replaced by the period of normalization, with political, military and union purges and the repeal of reforms, which thrust the country back into 1950s. The dissident movement, symbolized by the future Czech President Václav Havel, worked underground to counter the system and drew up Charter 77, a document that demanded human rights. The government responded with a prohibition of professional employment for the dissidents, higher education for their children, police harassment and prison time. All artists who wanted to continue working in their field were forced to sign the government-issued Anti-Charter.

In 1969, Czechoslovakia became a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic in a move to eliminate economic inequities between the two parts. A number of ministries were divided to cater to each part; however, the centralized grip of the Communist Party diminished the effects of federalization.

In the 80s, the regime again grappled with a stifling economic crisis, and the revolutions in neighboring socialist countries encouraged Czechoslovakia to take steps toward democracy.

Velvet Revolution

1989 in the World

Mikhail Gorbatchev’s address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York, in which he endorsed the rights for all nations to shape their destiny, was among the first signs of the worldwide crumbling of the Communist empire. Gorbatchev followed through with a unilateral withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops from Europe and Asia and rehabilitated victims of Stalin's rule. Elections in March 1989 saw Communist candidates defeated, which spurred calls for the secession of the small Soviet republics from the Soviet Union. Hungary started taking steps toward democracy by allowing other than Commmunist political parties, but Communist authorities in Prague brutally dispersed ad hoc anti-regime demonstrations and Romania imprisoned journalists brave enough to criticize its President Ceausescu. Bloodbath occurred at East Berlin's infamous Berlin Wall. In Poland, a series of strikes forced the government to forge a deal with Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarita movement. One million students in Beijing took to the streets hoping that Gorbachev’s visit to China would be followed by reforms; however, thousands of them were massacred at the Tchien-an-men Square.

November 1989

The demonstrations were planned for November 17 in commemoration of the November 17, 1939, Nazi attack against university dormitories in Czechoslovakia and the subsequent closure of universities for three years. In 1989, however, it was not only water hoses and spontaneous arrests but also sheer violence used against young people, which set in motion the events that unseated Communism in the country. The main protagonists of the Velvet Revolution were Prague students in , who solicited support of actors, lead by Vaclav Havel, Alexander Dubcek,

After 1989

http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_11.php

In 1989, the country became democratic again through the Velvet Revolution. In 1992 the growing nationalist tensions led to dissolution of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, as of January 1, 1993.

Administrative Division

- 1918–1927: comprised three lands — former Austrian territory of Bohemia, Moravia, and a small part of Silesia), and former Hungarian territory of Slovakia and Ruthenia divided into districts

- 1928–1938: four lands — Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia, and Subcarpathian Ruthenia divided into districts

- late 1938–March 1939 — Slovakia and Ruthenia became autonomous lands

- 1945–1948 — Ruthenia became part of the Soviet Union

- 1949–1992 — Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic established in 1969 (both dropped the word Socialist in 1990)

Economy

http://www.mfcr.cz/cps/rde/xchg/mfcr/hs.xsl/historie_min.html

Období první republiky 1918 - 1938

I. Vznik Československa a snaha o stabilizaci veřejných rozpočtů a měny (1918 - 1925)

II. Léta konjunktury (1926 - 1929)

III. Velká hospodářská krize (1930 - 1934)

IV. Za zachování národní svébytnosti (1935 - 1938)

V. Daňová a celní správa v období první republiky

I. Období druhé republiky (1938 - 1939)

II. Protektorát Čechy a Morava (1939 - 1945) III. Státní zřízení v exilu (1939 - 1945) IV. Léta omezené demokracie (1945 - 1948)

I. Nástup totalitního systému, jeho upevnění a krize (1948 - 1968)

II. Léta "reálného socialismu" (1968 - 1989)

III. Řešení následků druhé světové války (válečné reparace, měnové zlato) a problematiky náhrad za poválečné znárodnění

IV. Daňová a celní správa v období totality

Fotogalerie

I. Společenská a ekonomická transformace, vznik České republiky a její vstup do Evropské unie

II. Daňová a celní správa po roce 1989

After WWII, economy centrally planned with command links controlled by communist party, similar to Soviet Union. Large metallurgical industry but dependent on imports for iron and nonferrous ores.

- Industry: Extractive and manufacturing industries dominated sector. Major branches included machinery, chemicals, food processing, metallurgy, and textiles. Industry wasteful of energy, materials, and labor and slow to upgrade technology, but country source of high-quality machinery and arms for other communist countries.

- Agriculture: Minor sector but supplied bulk of food needs. Dependent on large imports of grains (mainly for livestock feed) in years of adverse weather. Meat production constrained by shortage of feed, but high per capita consumption of meat.

- Foreign Trade: Exports estimated at US$17.8 billion in 1985, of which 55 % machinery, 14 % fuels and materials, 16 % manufactured consumer goods. Imports at estimated US$17.9 billion in 1985, of which 41 % fuels and materials, 33 % machinery, 12 % agricultural and forestry products other. In 1986, about 80 % of foreign trade with communist countries.

- Exchange Rate: Official, or commercial, rate Kcs 5.4 per US$1 in 1987; tourist, or noncommercial, rate Kcs 10.5 per US$1. Neither rate reflected purchasing power. The exchange rate on the black market was around Kcs 30 per US$1, and this rate became the official one once the currency became convertible in the early 1990s.

- Fiscal Year: Calendar year.

- Fiscal Policy: State almost exclusive owner of means of production. Revenues from state enterprises primary source of revenues followed by turnover tax. Large budget expenditures on social programs, subsidies, and investments. Budget usually balanced or small surplus.

After WWII, country energy short, relying on imported crude oil and natural gas from Soviet Union, domestic brown coal, and nuclear and hydroelectric energy. Energy constraints a major factor in 1980s.

Demographics

Czechoslovakia's ethnic composition in 1987 was in a stark contrast to its pre-WWII state. The Sudeten Germans that made up the majority of the population in border regions had been forcibly expelled and Ruthenia had been ceded to the Soviet Union following World War II. Czechs and Slovaks, who represented two-thirds of the population in 1930, accounted for 94% by 1950.

While the aspirations of ethnic minorities had been the pivot of the First Republic's politics, they were no longer the case in the 1980s. Nevertheless, ethnicity continued to be a sensitive issue due to the distinct historical experiences and divergent aspirations of Czechs and Slovaks. From 1950 through 1983, the Slovak share of the total population increased steadily as the Czech portion declined by 4%. In 1983 the Czech-Slovak ratio equalled 2:1, but in the mid-1980s, Slovaks almost closed the gap in the number of births.

From Creation to Dissolution — Overview

|

Czechoslovakia (or Czecho-Slovakia) | 1918 - 1939; 1945 - 1992 |

|||||||

|

Austria-Hungary (Bohemia, Moravia, a part of Silesia, northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia) |

Czechoslovak Republic |

Sudetenland + other German territories "Upper Hungary" territories of Hungary |

Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) |

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) |

Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (ČSFR) |

Czech Republic Slovakia |

|

|

Czecho-Slovak Republic (ČSR) incl. autonomous Slovakia and Transcarpathian Ukraine (1938-1939) |

Protectorate WWII Slovak Republic |

||||||

|

(further) "Upper Hungary" of Hungary |

part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic |

Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine |

|||||

|

German occupation |

Communist era |

||||||

|

govern. in exile |

|||||||

Footnotes

- ↑ Playing the blame game, Prague Post, July 6th, 2005

- ↑ http://zpravy.idnes.cz/chcete-znicit-prahu-ptal-se-goring-hachy-f0x-/domaci.asp?c=A070315_093114_domaci_adb

- ↑ http://zpravy.idnes.cz/chcete-znicit-prahu-ptal-se-goring-hachy-f0x-/domaci.asp?c=A070315_093114_domaci_adb

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich_Agreement

- ↑ http://www.law.nyu.edu/eecr/vol11num1_2/special/rupnik.html

External Links

English Language

- Czechoslovak Republicdefunct link, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- "Munich Agreement" Wikipedia, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Czech Language

- “Czechoslovak Orders and Medals” Awards, Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- “Lidice a Ležáky“ Czech Republic History, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Gazdik, Jan March 15, 2007 ”Do You Want to Destroy Prague? Goring Asked Hacha” iDnes News, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Czechoslovak Resistance Movement in the West” Wars, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Emergence of Czechoslovakia and Shaping of our Borders” Jan Skokan’s History Website, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Mikulecky, Tomas “Emergence of Czechoslovakia” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement, the Role of the Three Kings and the Resistance Movement Role of Vladimir Krajina” History, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ”Life in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Assassination of Reynhard Heidrich” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Velvet Revolution or Eleven Days that Rocked Czechoslovakia” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.* “International Events of 1989” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Political Processes in the Czech Socialist Republic 1948-1989” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Timeline of November 17 Demonstrations” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Charter 77” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Velvet Revolution ‘89” 1989 Revolution, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.