Difference between revisions of "Cultural Revolution" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→World reaction) |

|||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

Estimates of the death toll, civilians and Red Guards, from various Western and Eastern sources<ref name="White"/> are about 500,000 in the true years of chaos of 1966—1969. In the trial of the so-called [[Gang of Four]], a Chinese court stated that 729,511 people had been persecuted of which 34,800 were said to have died. <ref>James P. Sterba, ''New York Times'', January 25, 1981</ref> However, the true figure may never be known since many deaths went unreported or were actively covered up by the police or local authorities. Other reasons are the state of Chinese demographics at the time, as well as the reluctance of the PRC to allow serious research into the period. | Estimates of the death toll, civilians and Red Guards, from various Western and Eastern sources<ref name="White"/> are about 500,000 in the true years of chaos of 1966—1969. In the trial of the so-called [[Gang of Four]], a Chinese court stated that 729,511 people had been persecuted of which 34,800 were said to have died. <ref>James P. Sterba, ''New York Times'', January 25, 1981</ref> However, the true figure may never be known since many deaths went unreported or were actively covered up by the police or local authorities. Other reasons are the state of Chinese demographics at the time, as well as the reluctance of the PRC to allow serious research into the period. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Historical views== | ==Historical views== | ||

Revision as of 04:20, 5 September 2008

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution better known simply the , Cultural Revolution(文革 - wéngé) was a struggle for power in the Communist Party of China in the late 1960s, in which hundreds of thousands of people died and which brought the People's Republic of China to the brink of civil war.

The Cultural Revolution was launched by Communist Party of China Chairman Mao Zedong and military leader Lin Biao in 1966 to regain control of the party after the disasters of the Great Leap Forward led to liberalizing reforms and a significant loss of power to rivals such as Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. Though Mao himself officially declared the Cultural Revolution to have ended in 1969, it continued during the period between 1969 and the arrest of the so-called Gang of Four in 1976.

Between 1966 and 1968, Mao's principal lieutenants, Lin Biao and Mao's wife Jiang Qing, acting on his instructions, organized a mass youth militia called the Red Guards to overthrow Mao's enemies and seize control of the state apparatus. In the chaos and violence that ensued, millions were persecuted and as many as half a million people may have died.

The official Chinese view separates Mao's "mistakes" during the Cultural Revolution from his earlier heroism and his general theories on Marxism-Leninism.

The Cultural Revolution remains a sensitive issue within the People's Republic of China today. Historical views which run counter to the version, either by suggesting that the Cultural Revolution was a good thing, or that Mao was either more or less culpable than the official history indicates, are routinely censored.

Background

Great Leap Forward

In 1957, after China's first Five-Year Plan, Mao Zedong called for an increase in the speed of growth of "socialism." To accomplish this goal, Mao began the Great Leap Forward, establishing special communes in the countryside and instituting a nationwide program of steel production using backyard furnaces. Industries soon went into turmoil because peasants were producing too much steel, which was often of very poor qualilty, while other areas were neglected. Meanwhile, farming implements like rakes and shovels were melted down for steel, impeding agricultural production. To make matters worse, in order to avoid punishment, local authorities frequently over-reported production numbers, which hid the problem for years. With the country having barely recovered from decades of war, the Great Leap Forward left the Chinese economy in shambles.

Reforms

Mao admitted serious negative results and called for dismantling the communes in 1959. However, he insisted that the Great Leap was 70 percent correct overall. In the same year, Mao resigned as chairman of the People's Republic, and the government was subsequently run by reform-minded leaders such as People's Republic Chairman Liu Shaoqi, Premier Zhou Enlai, and General Secretary Deng Xiaoping. Mao, however, remained as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. During this period, Mao formed a political alliance with Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. Among Liu's and Deng's reforms were a retreat from collectivism, which had failed miserably, and tentative moves toward a more open economy.

These moves away from the crippling effects of the Great Leap Forward howvever, did not result in an improvement in the lives of masses of the Chinese people, as the nation was now faced with the so-called "Three Years of Natural Disasters," which made recovery even more difficult. Food was in desperate shortage, and production fell dramatically, as much due to lasting effects of the failed Great Leap Forward campaign as to natural causes. An estimated 38 million people died from widespread famine during these years.

In response, Liu Shaoqi developed a policy to move more dramatically away from Maoist policies of collectivism and and state socialism. The success of his economic reforms won Liu prestige in the eyes of many Party members. Together with Deng Xiaoping, Liu began planning to gradually retire Mao from any real power, and to turn him into a figurehead.

The reformers, however, faced opposition from Maoist hardliners, and Mao, sensing a movement away from his revolutionary principles, initiated the Socialist Education Movement in 1963, to restore his political base, especially among the youth. Mao soon began criticizing Liu Shaoqi openly. By 1964, the Socialist Education Movement had become the new "Four Cleanups Movement", with the stated goal of the cleansing of politics, economics, ideas, and organization. The Movement was directed politically against Liu.

The Revolution begins

In late 1959, Beijing Deputy Mayor Wu Han had published a historical drama entitled "Hai Rui Dismissed from Office" (pinyin: Hai Rui Ba Guan). In the play, a virtuous official (Hai Rui) was dismissed by a corrupt emperor. The play initially received praise from Mao, but in 1965, his wife, Jiang Qing, published an article criticizing the play together with her protégé Yao Wenyuan. They labeled it a "poisonous weed" and an attack on Mao.

The Shanghai newspaper article received much publicity nationwide. Beijing Mayor Peng Zhen, a supporter of Wu Han, established a commission to study the issue, finding that the criticism of the play had gone too far. In May, 1966, Jiang Qing and Yao Wenyuan published new articles denouncing both Wu Han and Peng Zhen. Then, on May 16, following Mao's lead, the Politburo issued a formal notice criticizing Peng Zhen and disbanding his commission.

Soon, the Politburo launched the Cultural Revolution Group. Lin Biao, who would become the primary government spokesmen of the Cultural Revolution, declared: "Chairman Mao is a genius, everything the Chairman says is truly great; one of the Chairman's words will override the meaning of ten thousands of ours."

Soon, popular demonstrations were launched in support of Mao and in opposition to the reformers. On May 25, a young teacher of philosophy at Beijing University, Nie Yuanzi, wrote a dazibao ("big-character poster") labeling the director of the university and other professors as "black anti-Party gangsters." Some days later, Mao ordered the text of this big-character poster to be broadcast nationwide.

On May 29, 1966, in the Middle School attached to Tsinghua University, the first organization of Red Guards was formed, aimed at punishing reform-minded intellectuals and neutralizing Mao's political enemies. On June 1, 1966, the official People's Daily Party newspaper stated that all "imperialistic intellectuals" and their allies must be purged. On July 28, 1966, representatives of the Red Guards wrote a formal letter to Mao, arguing that mass purges and related social and political phenomena were justified and committing themselves to this effort. In an article entitled "Bombard the Headquarters," Mao responded with full support. Thus the Cultural Revolution began in earnest.

The Cultural Revolution

1966: The 16 Points and the Red Guards

On August 8, 1966, the Central Committee of the CCP passed its "Decision Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution" (also known as "the 16 Points"). This decision defined the Cultural Revolution as "a new stage in the development of the socialist revolution in our country, a deeper and more extensive stage." It declared:

Although the bourgeoisie has been overthrown, it is still trying to use the old ideas, culture, customs, and habits of the exploiting classes to corrupt the masses, capture their minds, and endeavor to stage a comeback... At present, our objective is to struggle against and crush those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road, to criticize and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic "authorities"...

The policy expanded the existing student movement and elevated it to the level of a nationwide mass campaign, calling not only students but also "the masses of the workers, peasants, soldiers, revolutionary intellectuals, and revolutionary cadres" to carry out the task of "transforming the superstructure" by writing big-character posters and holding "great debates." The decision granted extensive freedom of speech to criticize those in authority and unleashed millions of young people who had been intensely indoctrinated in Maoist thought since the establishment of the PRC.

The freedoms granted in the "16 Points" were LAO written into the PRC constitution as "the four great rights (四大自由)": the right to speak out freely, to air one's views fully, to write big-character posters, and to hold great debates. Red Guard unites were formed throughout the country, throwing the universities into turmoil and threatening politicians deemed to be "capitalist roaders."

Beginning August 16, 1966 millions of Red Guards from all over the country gathered in Beijing to see the great Chairman Mao. From the top of the Tiananmen Square gate, Mao and Lin Biao made frequent appearances to approximately 11 million adoring Red Guards. Mao praised their actions in the recent campaigns to develop socialism and democracy.

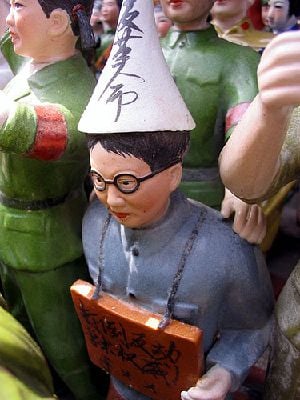

For two years, until July 1968 (and in some places much longer), student activists such as the Red Guards expanded their areas of authority. They began by passing out leaflets and posting the names of suspected "counter-revolutionaries" on bulletin boards. They assembled in large groups, held "great debates," and wrote educational plays. They held public meetings to criticize and solicit self-criticism from suspected "counter-revolutionaries."

Although the 16 Points forbade "physical struggle (武斗)" in favor of "verbal struggle" (文斗), the above-mentioned "struggle sessions" often led to physical violence. Party efforts to curb the violence were limited to verbal criticism, and sometimes even appearing to encourage "physical struggle." On August 22, 1966, Mao issued a public notice which stopped "all police intervention in Red Guard tactics and actions." Those in the police force who dared to defy this notice, were labeled "counter-revolutionaries."

On September 5, all Red Guards were encouraged to come to Beijing over a stretch of time. All fees, including accommodation and transportation, were to be paid by the government.

On October 10, Lin Biao publicly criticized Liu and Deng as "capitalist roaders" and "threats." Setting the stage for many more to follow, former defense minister Peng Dehuai, an early critic of the Great Leap Forward and a rival of Lin, was brought to Beijing to be publicly displayed and ridiculed. He was then purged from the Party.

1967: major power struggles

On January 3, 1967, Lin Biao and Jiang Qing collaborated to launch the "January Storm," in which many prominent Shanghai, municipal government leaders were publicly criticized and purged. As a result, Jiang's partner Wang Hongwen rose to power in the city and its CCP apparatus. In Beijing, Liu and Deng were once again the targets of criticism. This began a major political struggle among central government officials and local Party cadres, who seized the Cultural Revolution as an opportunity to accuse entrenched Party leaders of "counter-revolutionary activity."

On January 8, Mao once again praised the struggle against the "capitalist roaders" in a People's Daily editorial, urging all local governmental leaders to engage in "self-criticism," and in the criticism and purging of others. Purge after purge followed in China's local governments, some of which stopped functioning altogether. Involvement in some sort of public "revolutionary" activity was essential to avoid being purged, and it, too, was no guarantee. At the same time, major Red Guard organizations now began turning against each other in factional struggles and attempts to prove which units were the most revolutionary.

On April 6, Liu Shaoqi was openly and widely denounced by the large Zhongnanhai Red Guard faction. This was followed by a coutner-protest and mass demonstrations, most notably in Wuhan on July 20, which dared to denounce Jiang Qing behavior as "counter-revolutionary activity." She later flew to Wuhan to criticize the general in charge of the Wuhan area, Chen Zaidao. On July 22, Jiang Qing took the bold step of directing the Red Guards to replace the People's Liberation Army when needed.

1968: purges and curtailing the Red Guards

In the spring of 1968, a massive campaign promoted the already-adored Mao Zedong to a god-like status. However, the a consensus began to develop in the Party that the Red Guards were going too far, and that the military must establish order. On July 27, the Red Guards' power over the army was officially ended and the central government sent in units to protect many areas still being targeted by Red Guards. A year later, the Red Guard factions were dismantled entirely. In any case, from Mao and Lin's point of view, their purpose had been largely fulfilled, as Mao had largely consolidated his political power.

In early October, Mao began a purge of national level Pary officials. Many were sent to the countryside to work in labor camps. In the same month, at the Twelfth Plenum of the Eighth Party Congress, Liu Shaoqi was "forever expelled from the party," and Lin Biao was made the Party's Vice-Chairman, second only to Mao. Liu Shaoqi was sent to a detention camp, where he later died in 1969. Deng Xiaoping, was sent for a period of re-education three times and eventually found himself working in engine factory, until he was brought back years later by Zhou Enlai. Most of those accused were not so lucky, and many of them never returned.

In December 1968, Mao began the "Down to the Countryside Movement," which lasted for the next decade. "Young intellectuals" living in cities were ordered to the countryside. Most of these were recently graduated middle-school students. This move was largely a means of moving Red Guards out of the cities to the countryside, where they would cause less social disruption, although it was explained in terms of creating revolutionary consciousness by putting these city-bred student in touch with manual labor.

Lin Biao's rise and fall

On April 1, 1969, at the CCP's Ninth Congress, Lin Biao officially became China's second in charge, while still holding charge of the Army. With Mao aging, Liu Shaoqi already purged, and Zhou Enlai's power was gradually fading, his power appeared to be potentially unrivaled. The Party constitution was modified to designate Lin as Mao's official successor. Henceforth, at all occasions, Mao's name was to be linked with Lin's. Lin also held a place on the Politburo's powerful Standing Committee together with Mao, Chen Boda, Zhou Enlai, and Kang Sheng.

On August 23, 1970, at the Second Plenum of the CCP's Ninth Congress, a controversy developed over the issue of the restoration of the the position of President of the People's Republic of China|State President]], which Mao had previously abolished. Chen Boda, who had spoken in favor of restoring the office, was removed from the Standing Committee, a move which was also seen as a warning to Lin Biao. After the Ninth Congress, Mao began to suspect Lin of wanting supreme power and intending to oust Mao himself.

Subsequent events are clouded by divergences between official and alternative versions. In one account, Lin now moved to use his military power to oust Mao. Lin and his son Lin Liguo allegedly formed a group in Shanghai and began planning a coup. Other accounts hold Lin's son was solely responsible for the coup and portray Lin Biao as knowing nothing about it until the coup failed. Assassination attempts reportedly made against Mao in Shanghai, from September 8 to September 10, 1971.

After this nearly continuous reports circulated of Mao being attacked. One of these alleged an physical attack on Mao en route to Beijing in his private train. Another alleged that Lin had bombed a bridge that Mao was scheduled to cross to reach Beijing. Guards were placed every 33 to 66 feet on the railway tracks of Mao's route to avoid attempts on his life.

Whether or not these reports had a basis in fact, after September 11, 1971 Lin Biao never appeared in public again, nor did his primary backers, many of whom attempted to escape to Hong Kong. Most failed to do so and about 20 army generals loyal to Lin were arrested.

Official reports hold that on September 13, 1971, Lin Biao and his family attempted to flee by plane to the Soviet Union, but their plane crashed in Mongolia, killing all on board. On the same day, the Politburo met in an emergency session. Only on September 30 was Lin's death was annonced in Beijing, and a campaign was launched which would effectively discredit him as a power-hungry traitor who had attempted to use Mao and the Cultural Revolution for his own purposes.

The exact cause of the plane crash remains a mystery.

The "Gang of Four"

'Criticize Lin Biao, Criticize Confucius'

Mao had been severely shaken by the Lin Biao affair and and also needed a new succession plan. In September 1972, Shanghainese leader Wang Hongwen was transferred to work in Beijing for the central government, becoming the Party Vice-Chairman in the following year. At the same time, under the influence of Premier Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated and transferred back to Beijing.

In late 1973, however Jiang Qing three main backers—known later as the "Gang of Four"—launched the Pi-Lin Pi-Kong campaign, which translates as "Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius." Its prime target was Zhou Enlai, whose position Mao and the Gang of Four were seeking to weaken. Lin and Zhou both came to be characterized as having Confucianist tendencies because of their emphasis on Party bureaucracy rather than continued mass revolution. Although Zhou Enlai's name was never mentioned during this campaign, his historical namesake, the ancient Duke of Zhou, was a frequent target.

In October 1973, Zhou became gravely ill and was admitted into hospital care. Deng Xiaoping was named First Vice-Premier and took charge of the daily business of Party's state apparatus. Deng continued to expand Zhou's policies, while the Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius campaign failed to gain much momentum as a popular movement. In September 1975, Mao himself was too admitted into hospital with a serious illness.

1976: Cultural Revolution's end

On January 8, 1976 Zhou Enlai died of bladder cancer, and Deng Xiaoping delivered Zhou's official eulogy. In February, the Gang of Four s began to target Deng. On Mao's authority, Deng was once again demoted. However, Mao resisted selecting a member of the Gang of Four to become premier, instead choosing the relatively unknown Hua Guofeng.

With the main Party apparatus still in control and no mass Red Guard-type movement to support the Gang of Four's campaign popular opinion rallied around Zhou Enlai as a symbol of rational leadership. On April 5, China's traditional day of mourning, around two million people gathered in and around Tiananmen Square in honor of Chou, turning the assembly into a protest against the Gang of Four. Police were ordered to enter the area, clear the wreaths and messages of hate, and disperse the crowds. The Gang of Four pointed to Deng Xiaoping as the planner of this expression of public dissatisfaction.

On September 9, 1976, Mao Zedong died. Before dying, Mao had written a note to Hua Guofeng stating: "With you in charge, I'm at ease." Hence, Hua became the Party's chairman. Hua had been previously been considered to be lacking in political skill and ambition, and seemed to pose no threat to the Gang of Four in the power succession. However, Hua now proved his leadership ability. Influenced by prominent generals like Ye Jianying, and supported by the Army, and Deng Xiaoping's allies in the Party, Hua ordered the arrest of the Gang of Four. Their arrest brought the Cultural Revolution to its actual end.

Aftermath

Even though Hua Guofeng publicly denounced and arrested the Gang of Four in 1976, he continued to invoke Mao's name to justify his policies. Hua opened what was known as the Two Whatevers, saying "Whatever policy originated from Chairman Mao, we must continue to support," and "Whatever directions were given to us from Chairman Mao, we must continue to work on their basis." Like Deng, Hua's goal was to reverse the damage of the Cultural Revolution; but unlike Deng, who was not against new economic models for China, Hua intended to move the Chinese economic and political system towards Soviet-style planning of the early 1950s.

Soon afterwards, Hua found that without Deng Xiaoping it was hard for him to continue daily affairs of the state. On October 10, Deng Xiaoping personally wrote a letter to Hua asking to be transferred back to state and party affairs. Unconfirmed information allegedly stated that Politburo Standing Committee member Ye Jianying would resign if Deng was not allowed back into the Central Government. With increasing pressure from all sides, Hua decided to bring Deng back into regular state affairs, first naming him Vice-Premier of the State Council in July 1977, and to various other positions. In actuality, Deng had already become China's number two figure. In August, the Party's Eleventh Congress was held in Beijing, officially naming (in ranking order) Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping, Ye Jianying, Li Xiannian, and Wang Dongxing as the latest members of the Politburo Standing Committee.

In May, 1978, Deng seized the opportunity for his protégé, Hu Yaobang, to be further elevated to power. Hu published an article in the Bright Daily Newspaper making clever use of Mao's quotations while expanding Deng's power base. After reading this widely publicized article, almost everyone supported Hu and thus Deng. On July 1, Deng publicized Mao's self-criticism report of 1962 regarding the Great Leap Forward. With an expanding power base, in September 1978, Deng had already started to openly attack Hua Guofeng's "Two Whatevers."

On December 18, 1978, the Third Plenum of the Eleventh CCP Congress was held. Deng stated that "a liberation of thoughts" and "an accurate view leading to accurate results" was needed within the party. Hua Guofeng engaged in self-criticisms, stating that his own "Two Whatevers" was wrong. Wang Dongxing, formerly Mao's trusted supporter, was also criticized. At the Plenum, the Qingming Tiananmen Square incident was also politically rehabilitated. Liu Shaoqi was allowed a belated state funeral.

In the Fifth Plenum of the Eleventh CCP Congress, held in 1980, Peng Zhen and many others who had been purged during the Cultural Revolution were politically rehabilitated. Hu Yaobang was named General-Secretary and Zhao Ziyang, another of Deng's protégés, was named into the Central governing apparatus. In September, Hua Guofeng resigned, with Zhao Ziyang being named the new Premier. Deng was the Chairman of the Central Military Commission. By this time, Deng was the foremost and paramount figure in Chinese politics.

Effect

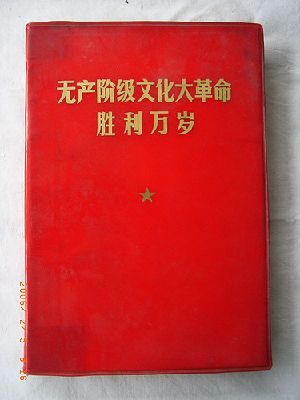

The effects of the Cultural Revolution directly or indirectly touched essentially all of China's populace. During the Cultural Revolution, much economic activity was halted, with "revolution" being the primary objective of many. The start of the Cultural Revolution brought huge numbers of Red Guards to Beijing, with all expenses paid by the government, and the railway system was in turmoil. Countless ancient buildings, artifacts, antiques, books, and paintings were destroyed by Red Guards. By December 1967, 350 million copies of Mao's Quotations had been printed.

Elsewhere, the ten years of the Cultural Revolution also brought the education system to a virtual halt. The university entrance exams were cancelled during this period, only being restored by Deng Xiaoping in 1977. Many intellectuals were sent to rural labor camps. Many survivors and observers suggest that almost anyone with skills over that of the average person was made the target of political "struggle" in some way. According to most Western observers as well as followers of Deng Xiaoping, this led to almost an entire generation of inadequately educated individuals.

Mao Zedong Thought had become the central operative guide to all things in China. The authority of the Red Guards surpassed that of the army, local police authorities, and the law in general. China's traditional arts and ideas were ignored, to praise from Mao. People were encouraged to criticize cultural institutions and to question their parents and teachers, which had been strictly forbidden in Confucian culture. This was emphasized even more during the Anti-Lin Biao; Anti-Confucius Campaign. However, no matter how much or how far the generations of one's parents and their ancestors could be questioned, one thing definitely could not, and these were the "thoughts of Mao Tse-tung."

The Cultural Revolution also brought to the forefront numerous, internal, power struggles within the Communist party, many of which had little to do with the larger battles between Party leaders, but resulted instead from local factionalism and petty rivalries. Members of different factions often fought on the streets, and political assassination, particularly in the more rural provinces, was common. One example, given by the writer Patrick French in his book Tibet, Tibet, is of the 'Big' and 'Small' factions in the Wuxuan county of the Guangxi Zhang Autonomous Region, which fought gun battles and threw bombs on the streets. The leader of the Small Faction, Zhou Weian, was eventually murdered in 1968, and his eight-month pregnant widow, Wei Shulan, forced to kneel under his dismembered body and denounce him.

Destruction of the antiques, historical sites, ancient culture

China's historical reserves, artifact,s and sites of interest suffered devastating damage as they were thought to be at the root of "old ways of thinking." Many artifacts were seized from private homes and often destroyed on the spot. There are no records of exactly how much was destroyed. Western observers suggest that much of China's thousands of years of history was in effect destroyed during the short ten years of the Cultural Revolution, and that such destruction of historical artifacts is unmatched at any time or place.

The most prominent symbol of academic research in archaeology, the journal Kaogu, did not publish during the Cultural Revolution. Religious persecution, in particular, intensified during this period, as religion was seen as being opposed to Marxist-Leninist and Maoist thinking. Some temples, however, such as the Longxing Temple near Shijiazhuang, survived because of the protection of local party members, who sometimes sent units of the PLA to protect it from mobs of Red Guards.

The Cultural Revolution was particularly devastating for minority cultures in China. This supposedly stemmed from Jiang Qing's personal animosity towards, and contempt for ethnic minorities. "The centrality of the Han ethnic group" was a major theme throughout this period. In Tibet, over 2,000 monasteries were destroyed, often with the complicity of local ethnic Tibetan Red Guards. In Inner Mongolia, many were executed during a ruthless witchhunt to find members of the allegedly "separatist" Inner Mongolian People's Party, which had actually been disbanded decades before. In Xinjiang, Koran books of the Uyghur people were burned and Muslim imams were reportedly paraded around with paint splashed on their persons.

In the ethnic Korean areas of northeast China, some killings occurred and language schools were destroyed. In Yunnan Province, the palace of the Dai people's king was torched, and an infamous massacre of Hui Muslim people at the hands of the People's Liberation Army, called the "Shadian Incident", claimed over 1,600 lives in 1975. It is ironic that all this activity and violence was directed at so-called "foreign influences," when the driving force behind Maoist thinking, the doctrines of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, had come into China, from "foreign outsiders" themselves.

Human rights violations, numerous deaths

Millions in China reportedly had their human rights annulled during the Cultural Revolution. Millions were forcibly displaced. During the Cultural Revolution, young people from the cities were forcibly moved to the countryside, where they were forced to abandon all forms of standard education for the propaganda teachings of the Communist Party of China.

So-called "crimes" against the government were brutally and publicly punished. People were forced to walk through the streets naked, were flogged publicly, or forced, some report, to sit in the jetliner position for hours. Many deaths occurred in police custody, although they were often covered up as "suicides." People had to carry two or more copies of Mao's Little Red Book to avoid being accused of not supporting Mao. Numerous individuals were accused, often on the flimsiest of grounds, of being foreign spies; to have, or have had, any contact with the world outside of China, could be extremely dangerous. Accusations were often based upon 'symbolic' language or gestures, such as the omission of certain strokes from a written character, or the placing of a picture of Mao in a subordinate position in a room. This paranoia may in part have derived from the tradition of Chinese revolutionaries, who used code-words and symbolic gestures in communication.

Some commentators argue that the Cultural Revolution years saw the Chinese people leave behind many uncritical habits of conformist and authoritarian thinking. This can be seen in the words of some of the student leaders of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. According to student leader Shen Tong in his book, Almost a Revolution, the trigger for the famous hunger-strikes of 1989 was a dazibao (big-character poster), a form of public political discussion that gained prominence in the Cultural Revolution and subsequently outlawed. When students organized demonstrations in their millions, something not seen since the Cultural Revolution, youths from outside Beijing rode the trains into Beijing and relied on the hospitality of the train workers and Beijing residents, just as their counterparts had ridden the trains freely during the Cultural Revolution.

Also, as in the Cultural Revolution, students formed factions, with names similar to those of Red Guard factions, using the term "Headquarters," for instance, and according to Shen Tong, these factions even went to the extent of kidnapping members of other factions, just as they had done in the Cultural Revolution. Finally, in a small minority of cases, some of the student leaders of 1989 had been youth activists in high school during the Cultural Revolution. It was as a result of the Cultural Revolution that criticism of high-level authority in public became more thinkable in the PRC, although criticism of Mao Zedong still remained entirely off-limits during the Cultural Revolution and criticism of his ideology remained off-limits afterwards.

Estimates of the death toll, civilians and Red Guards, from various Western and Eastern sources[1] are about 500,000 in the true years of chaos of 1966—1969. In the trial of the so-called Gang of Four, a Chinese court stated that 729,511 people had been persecuted of which 34,800 were said to have died. [2] However, the true figure may never be known since many deaths went unreported or were actively covered up by the police or local authorities. Other reasons are the state of Chinese demographics at the time, as well as the reluctance of the PRC to allow serious research into the period.

Historical views

Today, the Cultural Revolution is seen by most people inside and outside of China, including the Communist Party of China and Chinese democracy movement supporters, as an unmitigated disaster, and as an event to be avoided in the future. There are no politically significant groups within China that defend the Cultural Revolution. However, there are many workers and peasants in China who, left behind by economic liberalization and the widening rich-poor gap, feel nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution (as well as the Maoist Era in general), during which the proletariat was glorified.

Among those who condemn it, the causes and meaning of the Cultural Revolution remain highly controversial. Supporters of the Chinese democracy movement see the Cultural Revolution as an example of what happens when democracy is lacking and place responsibility for the Cultural Revolution on the Communist Party of China. Similarly, human rights activists and civil libertarians also see the Cultural Revolution as an example of the dangers of statism. Briefly put, these views of the Cultural Revolution attribute its cause to "too much government and too little popular participation."

By contrast, the official view of the Communist Party of China is that the Cultural Revolution is what can happen when one person establishes a cult of personality and manipulates the public in such a way as to destroy the party and state institutions. In this view, the Cultural Revolution is an example of too much popular participation in government, rather than too little; and is an example of the dangers of anarchy rather than statism. The consequence of this view is the consensus among the Chinese leadership that China must be governed by a strong party institution, in which decisions are made collectively and according to the rule of law, and in which the public has only limited input. After Mao's death, the Communist Party blamed the Gang of Four for the negative results of the Cultural Revolution. Liu Xiaobo argued that this is still the case, with the Gang of Four being used as convenient scapegoats, rather than focusing upon Mao Zedong's responsibility.

These contradictory views of the Cultural Revolution were put into sharp relief during the Tiananmen Protests of 1989, when both the demonstrators and the government justified their actions as being necessary to avoid another Cultural Revolution.

The relationship between Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution is also controversial. Although there is general agreement that Mao was responsible for the Cultural Revolution, there is considerable dispute concerning the effect of the Cultural Revolution on Mao's legacy. The PRC official version of history regards the Cultural Revolution as a serious error by Mao Zedong, whose contribution to history was 70-percent good and 30-percent bad. Using this formulation, the Party has argued that the Cultural Revolution should not denigrate Mao's earlier role as a heroic leader in fighting the Japanese, founding both the People's Republic of China and for developing the ideology which underlies the Communist Party of China. This allows the Party to condemn both the Cultural Revolution and Mao's role within it, without calling into question the ideology of the Party.

By contrast, writers such as Jung Chang argue that the Cultural Revolution was merely one of a series of events which illustrates Mao's low moral character. This interpretation of history has the effect of calling into question all of Mao's early accomplishments and indirectly the legitimacy of the Communist Party and the People's Republic of China.

The first museum specifically dedicated to the Cultural Revolution opened in mid-2005 as a privately funded museum opened in Guangdong province, created by Peng Qi'an, a former deputy mayor of Shantou. Peng himself was almost executed during the Cultural Revolution, and survived only due to a last-minute reprieve. He stated that he wanted future generations of Chinese to realise how large an impact the period had on China, and how much ordinary Chinese suffered. Although the museum continues to operate, publicity about the museum was suppressed by provincial authorities shortly after its opening.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Leys, Simon. Broken Images: Essays on Chinese Culture and Politics, Palgrave Macmillan, 1980, ASIN B0000T4012

- Leys, Simon. The Burning Forest: Essays on Chinese Culture and Politics; Holt, Rhiehart, and Winston; 1986. ISBN 978-0030050633

- Chan, Anita. Children of Mao: Personality Development and Political Activism in the Red Guard Generation, University of Washington Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0295962122

- Liu, Guokai. A Brief Analysis of the Cultural Revolution, M. E. Sharpe, 1987. ISBN 978-0873324359

- Chang, Tony H. (compiler). China During the Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976: A Selected Bibliography of English Language Works, Greenwood Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0313309052

- Sewart, Whitney. Mao Zedong, Twenty-First Century Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0822527978

External links

- Chinese propaganda posters gallery (Cultural Revolution, Mao, and others)

- Morning Sun - A Film and Website about Cultural Revolution

- Another website about the Cultural Revolution

- Attempts to document using eyewitness accounts events during the Cultural Revolution

- Chinese propaganda posters, Cultural Revolution statuettes, maoist stuff and revolutionary songs

- Chinese Museum Looks Back in Candor: Groundbreaking New Exhibit on Cultural Revolution Sparks Official Displeasure but Visitors' Praise from the Washington Post, June 3, 2005

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.