Difference between revisions of "Creek (people)" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 216: | Line 216: | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | * [http://museum.oneidanation.org/education/greenCorn.htm Green Corn Ceremony] | ||

*[http://www.perdidobaytribe.org/ Perdido Bay Tribe of Creek Indians] | *[http://www.perdidobaytribe.org/ Perdido Bay Tribe of Creek Indians] | ||

*[http://www.muscogeenation-nsn.gov/ Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma (official site)] | *[http://www.muscogeenation-nsn.gov/ Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma (official site)] | ||

*[http://www.genealogynation.com/creek/ Creek Nation Indian Territory Project] | *[http://www.genealogynation.com/creek/ Creek Nation Indian Territory Project] | ||

| − | *[http://www.LostWorlds.org/ocmulgee_mounds.html | + | *[http://www.LostWorlds.org/ocmulgee_mounds.html Ocmulgee Mounds: Creek/Muskogee Origins] |

| − | |||

*[http://ourgeorgiahistory.com/indians/Creek/index.html History of the Creek Indians in Georgia] | *[http://ourgeorgiahistory.com/indians/Creek/index.html History of the Creek Indians in Georgia] | ||

*[http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cocoon/legacies/AL/200002663.html Poarch Creek Indians in Alabama] | *[http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cocoon/legacies/AL/200002663.html Poarch Creek Indians in Alabama] | ||

| − | *[http://www.poarchcreekindians.org/ Poarch | + | *[http://www.poarchcreekindians.org/ Poarch Creek Indians] |

| − | *[http://www.tfn.net/Museum/language.html | + | *[http://www.tfn.net/Museum/language.html Creek Language] |

*[http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu/ssp/cgi-bin/ftaccess.cgi?_id=7f000001&dbs=ZLNA Southeastern Native American Documents, 1763-1842]. | *[http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu/ssp/cgi-bin/ftaccess.cgi?_id=7f000001&dbs=ZLNA Southeastern Native American Documents, 1763-1842]. | ||

| − | *[http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-579 | + | *[http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-579 Creek Indians] |

| − | *[http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1088 | + | *[http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1088 Creeks in Alabama] |

| − | + | ||

*[http://www.southernspaces.org/con_time.html#fife_cemetery "Fife Family Cemetery," ''Southern Spaces''—a short film on Creek Christian burial practices] | *[http://www.southernspaces.org/con_time.html#fife_cemetery "Fife Family Cemetery," ''Southern Spaces''—a short film on Creek Christian burial practices] | ||

* The [http://www.wm.edu/linguistics/creek Creek Language Archive]. This site includes a draft of a Creek textbook, which may be [http://www.wm.edu/linguistics/creek/learning_creek.html downloaded] in .pdf format (''Pum Opunvkv, Pun Yvhiketv, Pun Fulletv: Our Language, Our Songs, Our Ways'' by Margaret Mauldin, Jack Martin, and Gloria McCarty). | * The [http://www.wm.edu/linguistics/creek Creek Language Archive]. This site includes a draft of a Creek textbook, which may be [http://www.wm.edu/linguistics/creek/learning_creek.html downloaded] in .pdf format (''Pum Opunvkv, Pun Yvhiketv, Pun Fulletv: Our Language, Our Songs, Our Ways'' by Margaret Mauldin, Jack Martin, and Gloria McCarty). | ||

Revision as of 14:57, 24 November 2008

Template:Confuse

| Creek |

|---|

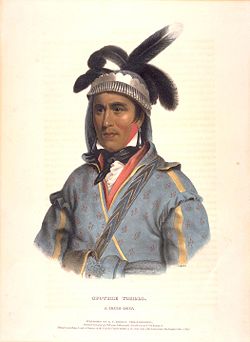

| Opothleyahola, Muscogee Creek Chief, 1830s |

| Total population |

| 50,000-60,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Oklahoma, Alabama) |

| Languages |

| English, Creek |

| Religions |

| Protestantism, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Muskogean peoples: Alabama, Coushatta, Miccosukee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole |

The Creek are an American Indian people originally from the southeastern United States, also known by their original name Muscogee (or Muskogee), the name they use to identify themselves today.[1] Mvskoke is their name in traditional spelling. Modern Muscogees live primarily in Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. Their language, Mvskoke, is a member of the Creek branch of the Muskogean language family. The Seminole are close kin to the Muscogee and speak a Creek language as well. The Creeks were considered one of the Five Civilized Tribes.

History

The early historic Creeks were probably descendants of the mound builders of the Mississippian culture along the Tennessee River in modern Tennessee[2] and Alabama, and possibly related to the Utinahica of southern Georgia. More of a loose confederacy than a single tribe, the Muscogee lived in autonomous villages in river valleys throughout what are today the states of Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama and consisted of many ethnic groups speaking several distinct languages, such as the Hitchiti, Alabama, and Coushatta. Those who lived along the Ocmulgee River were called "Creek Indians" by British traders from South Carolina. Eventually the name was applied to all of the various inhabitants of Creek towns, which were divided into the Lower Towns of the Georgia frontier on the Chattahoochee River, Ocmulgee River, and Flint River, and the Upper Towns of the Alabama River Valley.

The Lower Towns included Coweta, Cusseta (Kasihta, Cofitachiqui), Upper Chehaw (Chiaha), Hitchiti, Oconee, Ocmulgee, Okawaigi, Apalachee, Yamasee (Altamaha), Ocfuskee, Sawokli, and Tamali. The Upper Towns included Tuckabatchee, Abhika, Coosa (Kusa; the dominant people of East Tennessee and North Georgia during the Spanish explorations), Itawa (original inhabitants of the Etowah Indian Mounds), Hothliwahi (Ullibahali), Hilibi, Eufaula, Wakokai, Atasi, Alibamu, Coushatta (Koasati; they had absorbed the Kaski/Casqui and the Tali), and Tuskegee ("Napochi" in the de Luna chronicles).

Cusseta (Kasihta) and Coweta are still the two principal towns of the Creek Nation. Traditionally, the Cusseta and Coweta bands are considered the earliest members of the Creek Nation.[3]

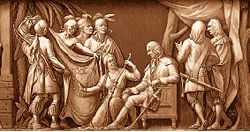

James Oglethorpe (December 22, 1696 – June 30, 1785) was a British general, a philanthropist, and was the founder of the colony of Georgia. For the purpose of providing a refuge for persons who had become insolvent and for oppressed Protestants on the continent, he proposed the settlement of a colony in America between Carolina and Florida. Oglethorpe sailed for 88 days, arriving in Charleston, South Carolina on the ship Anne, in late 1732, and settled near the present site of Savannah, Georgia on February 12, 1733. He negotiated with the Creek tribe for land and established a series of defensive forts, most notably Fort Frederica, of which substantial remains can still be visited.

Revolutionary War era

Like many Native American groups east of the Mississippi and Louisiana Rivers, the Creeks were divided in the American Revolutionary War. The Lower Creeks remained neutral; the Upper Creeks allied with the British and fought the American Patriots.

After the war ended in 1783, the Creeks discovered that Britain had ceded Creek lands to the now independent United States. Georgia began to expand into Creek territory. Creek statesman Alexander McGillivray rose to prominence as he organized pan-Indian resistance to this encroachment and received arms from the Spanish in Florida to fight trespassers. McGillivray worked to create a sense of Creek nationalism and centralize Creek authority. He struggled against village leaders who individually sold land to the United States. By the Treaty of New York in 1790, McGillivray ceded a significant portion of the Creek lands to the United States under President George Washington in return for federal recognition of Creek sovereignty within the remainder. McGillivray died in 1793, however, and Georgia continued to expand into Creek territory.

In 1799 English adventurer William Augustus Bowles was elected director general of the State of Muskogee by a congress of Creeks and Seminoles.As both Spain and the USA claimed the land, Bowles hoped to be able to create an independent Creek nation, the State of Muskogee.

First to Civilize

George Washington, the first U.S. President, and Henry Knox, the first U.S. Secretary of War, proposed a cultural transformation of the Native Americans.[4] Washington believed that Native Americans were equals, but that their society was inferior. He formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process, and it was continued under President Thomas Jefferson.[5] Noted historian Robert Remini wrote "they presumed that once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans."[6] Washington's six-point plan included impartial justice toward Indians; regulated buying of Indian lands; promotion of commerce; promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Indian society; presidential authority to give presents; and punishing those who violated Indian rights.[7] The Creeks would be the first Native Americans to be civilized under Washington's six-point plan. The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole would follow the Creeks efforts to benefit under Washington's new policy of civilization.

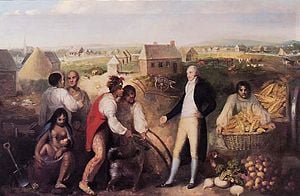

In 1796, Washington appointed Benjamin Hawkins as General Superintendent of Indian Affairs dealing with all tribes south of the Ohio River. He personally assumed the role of principal agent to the Creeks. He moved to the area that is now Crawford County in Georgia. He began to teach agricultural practices to the tribe, starting a farm at his home on the Flint River. In time, he brought in slaves and workers, cleared several hundred acres and established mills and a trading post as well as his farm.

For years, he would meet with chiefs on his porch and discuss matters. He was responsible for the longest period of peace between the settlers and the tribe, overseeing 19 years of peace. When a fort was built, in 1806, to protect expanding settlements, just east of modern Macon, Georgia, it was named Fort Benjamin Hawkins.

Hawkins was dis-heartened and shocked with the Creek War which destroyed his life work of improving Creek Native Americans quality of life. Hawkins saw much of his work toward building a peace destroyed in 1812. A group of Creeks, led by Tecumseh were encouraged by British agents to resistance against increasing settlement by whites. Although he personally was never attacked, he was forced to watch an internal civil war among the Creeks, the war with a faction known as the Red Sticks, and their eventual defeat by Andrew Jackson.

Red Stick War

The Creek War of 1813-1814, also known as the Red Stick War, began as a civil war within the Creek Nation, only to become enmeshed within the War of 1812. Inspired by the fiery eloquence of the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and their own religious leaders, Creeks from the Upper Towns, known to the Americans as Red Sticks, sought to aggressively resist white immigration and the "civilizing programs" administered by U.S. Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins. Red Stick leaders William Weatherford (Red Eagle), Peter McQueen and Menawa violently clashed with the Lower Creeks led by William McIntosh, who were allied with the Americans.

On August 30, 1813, Red Sticks led by Red Eagle attacked the American outpost of Fort Mims near Mobile, Alabama, where white settlers and their Indian allies had gathered. The Red Sticks captured the fort by surprise, and amassacre ensued, as prisoners — including women and children — were killed. Nearly 250 died, and panic spread across the American southwestern frontier.

Tennessee, Georgia, and the Mississippi Territory sent militia units deep into Creek territory. Although outnumbered and poorly armed, the Red Sticks put up a desperate fight from their strongholds. On March 27, 1814, General Andrew Jackson's Tennessee militia, aided by the 39th U. S. Infantry Regiment plus Cherokee and Creek allies, finally crushed Red Stick at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River.

Though the Red Sticks had been soundly defeated and about 3,000 Upper Creeks died in the war, the remnants held out several months longer. In August 1814, exhausted and starving, they surrendered to Jackson at Wetumpka (near the present city of Montgomery, Alabama). On August 9, 1814, the Creek nation was forced to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which ended the war and required them to cede some 20 million acres (81,000 km²) of land—more than half of their ancestral territorial holdings—to the United States. Even those who had fought alongside Jackson were compelled to cede land, since Jackson held them responsible for allowing the Red Sticks to revolt. The state of Alabama was carved largely out of their domain and was admitted to the United States in 1819.

Many Creeks refused to surrender and escaped to Florida. Some allied themselves with Florida Indians (who eventually become collectively called the Seminoles) and the British against the Americans. They were involved on both sides of the Seminole War in Florida.

Culture

Language

The Creek language, also known as Muscogee (Mvskoke in Creek), is a Muskogean language spoken by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and Seminole Indians in Oklahoma, Florida, and (to a lesser extent) Alabama and Georgia.

The traditional Creek alphabet was adopted by the tribe in the late 1800s (Innes 2004). There are 20 letters. Although it is based on the Latin alphabet, some of the sounds are vastly different from those in English — in particular those represented by c, e, i, r, and v.

Mythology

The Creek believe that the world was originally entirely underwater. The only land was a hill, called Nunne Chaha, and on the hill was a house, wherein lived Esaugetuh Emissee ("master of breath"). He created humanity from the clay on the hill.

The Creek also venerated the Horned Serpent Sint Holo, who appeared to suitably wise young men.

The shaman was called an Alektca.

In the underworld, there was only chaos and odd creatures. Master of Breath created Brother Moon and Sister Sun, as well as the four directions to hold up the world.

The first people were the offspring of Sister Sun and the Horned Serpent. These first two Creeks were Lucky Hunter and Corn Woman, denoting their respective roles in Creek Society.

Hisagita-imisi (meaning "preserver of breath"; also Hisakitaimisi) was the supreme god, a solar deity. He is also called Ibofanga ("the one who is sitting above (us)").

Green corn ceremony

The Green Corn Ceremony is an English term that refers to a general religious and social theme celebrated by a number of American Indian peoples of the Eastern Woodlands and the Southeastern tribes. The Green Corn festivals are also known to have been practiced by the Mississippian Mound builders as part of their Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.

Green Corn festivals are still practiced today by many different native peoples of the Southeastern Woodland Culture. The Green Corn Ceremony typically coincides with late summer and was tied to the ripening of the corn crops. The ceremony is marked with dancing, feasting, fasting and religious observations.

In the Muskogee tradition of the Southeastern Creek and Seminole peoples, the Green Corn festival is called Posketv (Bus-get-uh) which means 'to Fast'. This ceremony is celebrated as the new year of the Stomp dance society and takes place on the central ceremonial Square Ground which is an elevated square platform with the flat edges of the square facing the cardinal directions. Arbors are constructed upon the flat edges of the square in which the men sit facing one of the four directions. This is encircled by a ring-mound of earth outside of which are constructed the clan houses. In the center of this is the ceremonial fire, which is referred to by many names including 'Grandfather' fire. Ceremonially, this fire is the focus of the songs and prayers of the people and is considered to be a living sacred being who transmits our prayers to Ofvnkv (the One Above) and Hsakvtvmes (the Breathmaker). The whole general ceremony centers on the relighting of this ceremonial fire.

The Posketv is the Creek and Seminole New Year. At this time all offenses are forgiven save for rape and murder which were executable or banishable offenses. Historically nearly everything would be torn down and replaced within the tribal town. In modern tribal towns and Stomp Dance societies only the ceremonial fire, the cook fires and certain other ceremonial objects will be replaced. Everyone usually begins gathering by the weekend prior to the Posketv, working, praying, dancing and fasting off and on until the big day.

The first day of the Posketv is the Ribbon or "Ladies" Dance in which the women of the community perform a purifying dance to prepare the ceremonial ground for the renewal ceremony. Following this there is a family meal and by midnight all the men of the community begin fasting. The men sleep right outside the ceremonial square to guard it from intruders.

The men rise before dawn on the second day and remove the previous year’s fire and clean the ceremonial area from all coals and ash. There are numerous dances and rites that are performed throughout the day as the men continue to fast in the hot southern summer. During this time the women clean out their cook-fires as the central ceremonial fire is relit and nurtured with a special medicine made by the Hillis Hiya. Many Creeks still practice the sapi or ceremonial scratches, a type of bloodletting in the mid afternoon. Then the head woman of each family camp comes to the ceremonial circle where they are handed some hot coals from the newly established ceremonial fire, which they take back to their camp and start their cook fires.

During this time, men who have earned the right to a war-name are named and the Feather Dance is performed. This dance is a blessing of the area and a rite of passage for youths becoming men. It consists of 16 different performances including a display of war-party tactics and virility.

The fasting usually ends by supper-time after the word is given by the women that the food is prepared, at which time the men march in single-file formation down to a body of water, typically a flowing creek or river for a ceremonial dip in the water and private men’s meeting. They then return to the ceremonial square and perform a single Stomp Dance before retiring to their home camps for a feast. During this time, the participants in the medicine rites are not allowed to sleep, as part of their fast. At midnight a Stomp Dance ceremony is held, which includes fasting and continues on through the night. This ceremony usually ends shortly after dawn, part the participants in the previous day’s rites do not sleep till mid-day.

Posketv the "Ceremonial Fast," commonly referred to as “Green Corn” in English is the central and most festive holiday of the traditional Muskogee people. It represents not only the renewal of the annual cycle, but of the community’s social and spiritual life as a whole. This is symbolically associated with the return of summer and the ripening of the new corn.

Present

Most Muscogees were removed to Indian Territory, although some remained behind. There are Muscogees in Alabama living near Poarch Creek Reservation in Atmore (northeast of Mobile), as well as Creeks in essentially undocumented ethnic towns in Florida. The Alabama reservation includes a bingo hall and holds an annual powwow on Thanksgiving. Additionally, Muscogee descendants of varying degrees of acculturation live throughout the southeastern United States. The tribal government operates a budget in excess of $106 million, has over 2,400 employees, and maintains tribal facilities and programs in eight administrative districts. The nation operates several significant tribal enterprises, including the Muscogee Document Imaging Company; travel plazas in Okmulgee, Muskogee and Cromwell, Oklahoma; construction, technology and staffing services; and major casinos in Tulsa and Okmulgee. The tribal population is fully integrated into the larger culture and economy of Oklahoma, with Muscogee Nation citizens making significant contributions in every field of endeavor, while continuing to preserve and share a vibrant tribal identity through events such as annual festivals, ball-games, and language classes. The Stomp Dance and Green Corn Ceremony are both highly revered gatherings and rituals that have largely remained non public and not by coincidence "Pure." The Nation's historic old Council House, built in 1878 and located in downtown Okmulgee, was completely restored in the 1990s and now serves as a museum of tribal history.

Famous Creek

- Lt. Col. Ernest Childers, First American Indian to Receive World War II Congressional Medal of Honor[1]

- William McIntosh, Lower Creek Mico [2] [3]

- Acee Blue Eagle, artist.

- Johnnie Diacon, artist, Thlopthlocco Tribal Town (Raprakko Etvlwv), Deer Clan (Ecovlke).

- Joy Harjo, Native American poet.

- Retha Gambaro, artist.

- Suzan Shown Harjo

- Jim Pepper, jazz musician.

- Will Sampson, film actor, noted for his performance in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975).

- Synyster Gates, lead guitar player from the band Avenged sevenfold has Creek ancestry.

- Frank Van Zant, who also went by the name Chief Rolling Mountain Thunder. He built and lived in the Thunder Mountain Indian Monument in Imlay, Nevada.[8]

- Jack Jacobs, football player

- James McHenry, Confederate Major, Methodist minister, and important Creek leader

- Cynthia Leitich Smith, Children's book author noted for "Jingle Dancer"

- Thomas Francis Meagher, Jr. (cousin of Brig. Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher) Creek Historian, Rough Rider

- Micah Ian Wright, film, television & videogame writer, chair of the Writers Guild of America's American Indian Writers Committee.

- Carrie Underwood, country singer.

- William Harjo LoneFight, noted Native American author, entrepreneur and nationally known expert in the revitalization of Native American Languages and Cultural Traditions.

Notes

- ↑ Transcribed documents Sequoyah Research Center and the American Native Press Archives

- ↑ Finger, John R. (2001). Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Indiana University Press, p. 19. ISBN 0-253-33985-5.

- ↑ Transcribed documents Sequoyah Research Center and the American Native Press Archives

- ↑ Perdue, Theda [2003]. "Chapter 2 "Both White and Red"", Mixed Blood Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South. The University of Georgia Press. ISBN 082032731X.

- ↑ Remini, Robert [1977, 1998]. ""The Reform Begins"", Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. ISBN 0965063107.

- ↑ Remini, Robert [1977, 1998]. ""Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit"", Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. ISBN 0965063107.

- ↑ Miller, Eric (1994). George Washington And Indians (HTML). Eric Miller. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ Background of Thunder Mountain Monument, thundermountainmonument.com, Retrieved on 2007-11-26.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ethridge, Robbie. 2003. Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807854956

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland. 1993. Deerskins & Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685-1815. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Perdue, Theda. 2003. Mixed Blood Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South. The University of Georgia Press. ISBN 082032731X.

- Jackson, Harvey H. 1995. Rivers of History-Life on the Coosa, Tallapoosa, Cahaba and Alabama. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817307710

- Swanton, John R. 1922. Early History of the Creek Indians and their Neighbors. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Swanton, John R. 1928. Forty-Second Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Raymond D. Fogelson (ed.) 2004. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 14: Southeast. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- McEwan, Bonnie G. (ed.) 2001. Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0813017785

- Finger, John R. 2001. Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253339855

- Remini, Robert V. 1998. Andrew Jackson: The Course of American Freedom, 1822-1832. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801859123

- Lewis, David Lewis Jr., and Ann T. Jordan. 2008. Creek Indian Medicine Ways: The Enduring Power of Mvskoke Religion. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826323682

- Howard, James H., and Willie Lena. 1990. Oklahoma Seminoles, Medicines, Magic and Religion. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806122382

- Hudson, Charles M. 1976. The Southeastern Indians. University of Tennessee. ISBN 0870492489

- Wright, J. Leitch, Jr. 1990. Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803297289

- Weisman, Brent Richards. 1999. Unconquered People: Florida's Seminole and Miccosukee Indians. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0813016630

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

- Perdido Bay Tribe of Creek Indians

- Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma (official site)

- Creek Nation Indian Territory Project

- Ocmulgee Mounds: Creek/Muskogee Origins

- History of the Creek Indians in Georgia

- Poarch Creek Indians in Alabama

- Poarch Creek Indians

- Creek Language

- Southeastern Native American Documents, 1763-1842.

- Creek Indians

- Creeks in Alabama

- "Fife Family Cemetery," Southern Spaces—a short film on Creek Christian burial practices

- The Creek Language Archive. This site includes a draft of a Creek textbook, which may be downloaded in .pdf format (Pum Opunvkv, Pun Yvhiketv, Pun Fulletv: Our Language, Our Songs, Our Ways by Margaret Mauldin, Jack Martin, and Gloria McCarty).

- Comprehensive Creek Language materials online.

- The official website for the Muskogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma

- Ethnologue report for Creek

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.