Difference between revisions of "Calligraphy" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (88 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Calligraphy.malmesbury.bible.arp.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Calligraphy in a [[Latin]] [[Bible]] of | + | {{Copyedited}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} |

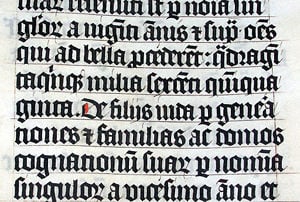

| + | [[Image:Calligraphy.malmesbury.bible.arp.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Calligraphy in a [[Latin]] [[Bible]] of 1407 C.E. on display in [[Malmesbury Abbey]], [[Wiltshire]], [[England]]. The Bible was hand written in [[Belgium]], by Gerard Brils, for reading aloud in a [[monastery]].]] | ||

| − | + | '''Calligraphy''' (from the [[Greek language|Greek]] meaning ''{{polytonic|κάλλος}}'' ''kallos'' "beauty" + ''{{polytonic|γραφή}}'' ''graphẽ'' "writing") is a form of ornamental handwriting found in various cultures throughout the world and whose origins date back to ancient times. A contemporary definition of calligraphic practice would be: "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious and skillful manner."<ref>Claude Mediavilla, Alan Marshall, Mark Van Stone, Gerard Xuriguera, and Donald Jackson, ''Calligraphy: From Calligraphy to Abstract Painting.'' (Wommelgem, Belgium: Scirpus Publications, 1996, ISBN 9080332518), 18.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | '''Calligraphy''' (from the [[Greek language|Greek]] meaning ''{{polytonic|κάλλος}}'' ''kallos'' "beauty" + ''{{polytonic|γραφή}}'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Calligraphy | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Calligraphic works range from functional inscriptions and hand lettering to [[fine art]] pieces where the artistic manifestation may take precedence over the legibility of the letters. Well-crafted calligraphy differs from [[typography]] and non-classical hand-lettering in that characters are disciplined yet fluid and spontaneous. Often they are improvised at the moment of writing. | ||

| + | Calligraphy has played a significant role in the history of many cultures and their languages. [[Muslim]]s were among those who valued calligraphy not only as [[art]] but also used it as the ultimate expression of [[God]]’s words.<ref>[http://www.islamicarchitecture.org/art/islamic-calligraphy.html Islamic Calligraphy] ''Islamicarchitecture.org.'' Retrieved May 19, 2008.</ref> Ancient and holy books of many [[religion]]s have been handwritten in illuminated calligraphic script. In present times, calligraphy continues to flourish in the form of [[marriage|wedding]] and event invitations, [[typography]], original hand-lettered logo design, commissioned calligraphic art, [[map|maps]], and other works involving writing. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Twentieth century calligraphy master, [[Edward Johnston]], best described the process of writing calligraphy when he advised: "All rules must give way to [[Truth]] and [[Freedom]]."<ref>Edward Johnston, ''Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering'' (London: Pitman, 1977, ISBN 0273010646).</ref> | ||

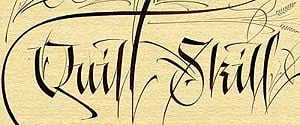

| + | [[Image:Westerncalligraphy.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Traditional western calligraphy with a [[Blackletter|gothic]] flavor by Denis Brown.<ref>[http://www.quillskill.com/frameset/frameset.htm Calligraphy by Denis Brown] ''Quillskill.com.'' Retrieved May 23, 2008.</ref>]] | ||

== East Asian calligraphy == | == East Asian calligraphy == | ||

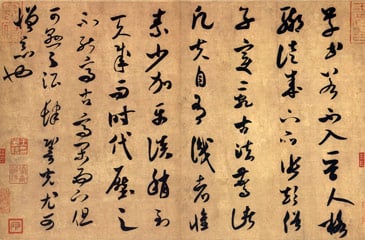

| − | [[Image:Mifu01.jpg|frame| | + | [[Image:Mifu01.jpg|frame|250px|right|Chinese calligraphy written by [[Song Dynasty]] (1051-1108 C.E.) poet [[Mi Fu]].]] |

| − | + | [[Image:Calligrapher Yiheyuan.jpg|thumb|right|150px|A calligrapher in action at Suzhou Street, Yiheyuan (the summer palace), [[Beijing]].]] | |

{{main|East Asian calligraphy}} | {{main|East Asian calligraphy}} | ||

Calligraphy is considered an important art in [[East Asia]] and as the most refined form of East Asian [[painting]]. | Calligraphy is considered an important art in [[East Asia]] and as the most refined form of East Asian [[painting]]. | ||

| − | It has influenced most major art styles, including 'sumi-e', a style of Chinese and | + | It has influenced most major art styles, including 'sumi-e', a style of Chinese and [[Japan]]ese [[ink and wash painting]] which uses similar tools and techniques and is based entirely on calligraphy. |

| − | [[East Asian calligraphy]] typically uses ink brushes to write Chinese characters which are called by various names: | + | [[East Asian calligraphy]] typically uses ink brushes to write [[Chinese characters]] which are called by various names: 'Hanzi' in [[Chinese language|Chinese]], 'Kanji' in [[Japanese language|Japanese]], and 'Hanja' in [[Korean language|Korean]] and [[Hán Tự]] in [[Vietnamese language|Vietnamese]]. The term calligraphy: in Chinese, ''Shufa'' 書法, in Japanese ''Shodō'' {{lang|ja|書道}}, in Korean, ''Seoye'' 書藝, all mean 'the way of writing'. |

{| cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" border="1" class="prettytable" | {| cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" border="1" class="prettytable" | ||

| Line 26: | Line 24: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | English name | ! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | English name | ||

| − | ! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | [[Hanzi]](Pinyin) | + | ! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | [[Hanzi]] (Pinyin) |

! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | Hangul ([[Revised Romanization of Korean|RR]]) | ! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | Hangul ([[Revised Romanization of Korean|RR]]) | ||

! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | Rōmaji | ! bgcolor="#EEEAE1" | Rōmaji | ||

| Line 38: | Line 36: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Clerical script (Official script) | | Clerical script (Official script) | ||

| − | | 隸書<br>(隷書)(Lìshū) | + | | 隸書<br/>(隷書)(Lìshū) |

| 예서(Yeseo) | | 예서(Yeseo) | ||

| Reisho | | Reisho | ||

| Line 63: | Line 61: | ||

==Indian Calligraphy== | ==Indian Calligraphy== | ||

| − | + | [[Persia]]n and [[Arab]]ic script is thought to have influenced [[India|Indian calligraphy]], although the scripts used are somewhat different. The flowing Persian script was thought to have influenced the writing style of Indian epics. Calligraphy in India was especially influenced by [[Sikhism]] whose holy book has been traditionally handwritten and illuminated. In ancient times the lack of modern [[printing]] technology resulted in a rich heritage of calligraphy in many Indian languages. | |

| − | [[Image: | + | ==Nepalese calligraphy== |

| + | [[Image:ज्वजलपा.jpg|right|thumb|200px|Rajna Script]] | ||

| + | Nepalese calligraphy has a huge impact on [[Mahayana]] and [[Vajrayana]] [[Buddhism]]. [[Ranjana script]] is the primary form of this calligraphy. | ||

| − | In | + | It is primarily used for writing Nepal Bhasa but is also used in monasteries of [[India]], [[Tibet]], coastline [[China]], [[Mongolia]], and [[Japan]].<ref>Nepal Lipi - The Nepalese Scripts ''Jwajalapa.com.''</ref> In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist traditions, it is famously used to write various [[mantra]]s including the ''Om mane padme hum'' mantra of Aryawalokirteshwar, the Mantra of Arya Tara ''Om tare tuttare ture svaha'', and the mantra of Manjushree ''Om ara pa cana dhi''. The script is also used in Hindu scriptures. |

| + | |||

| + | In Tibet, the script is called Lantsa and used to write the original texts of [[Sanskrit]]. | ||

==Tibetan Calligraphy== | ==Tibetan Calligraphy== | ||

| − | Calligraphy is central to [[Tibet|Tibetan]] culture. | + | Calligraphy is central to [[Tibet|Tibetan]] culture. The script is derived from Indic scripts. As in [[China]], the nobles of Tibet, such as the [[High Lama]]s and [[oracle|oracles]] of the [[Potala Palace]], were usually skilled calligraphers. For several centuries, Tibet has been a center of [[Buddhism]], a religion that places a great deal of significance on the written word. Almost all high religious writing involved calligraphy, including letters sent by the [[Dalai Lama]] and other religious, and secular, figures of authority. Calligraphy is particularly evident on their [[prayer wheels]], although this calligraphy was forged rather than scribed, much like Arab and Roman calligraphy is often found on buildings. Although originally done with a brush, Tibetan calligraphers now use chisel tipped pens and markers. |

==Persian calligraphy== | ==Persian calligraphy== | ||

| − | + | ====History of Persian Calligraphy==== | |

| + | The history of calligraphy in [[Persia]] dates back to the pre-Islam era. In [[Zoroastrianism]], beautiful and clear writings were highly valued.<ref>[http://www.stanford.edu/~shahlamf/alphabet.htm Persian Alphabet] ''Stanford.edu.'' Retrieved May 19, 2008.</ref> The three main forms of Persian calligraphy are called: ''Nasta'liq script'', ''Shekasteh-Nasta'liq script'' and ''Naghashi-khat'' script. “Nasta'liq” is the most popular contemporary style among classical Persian calligraphy scripts and Persian calligraphers call it the “Bride of the Calligraphy Scripts.” This calligraphy style has been based on rigid structure that has changed very little over the years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is believed that ancient Persian script was invented by about 500-600 B.C.E. to provide monument inscriptions for the [[Achaemenid kings]]. These scripts consisted of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal nail-shape letters—the reason it is called “Script of Nails” (Khat-e-Mikhi) in [[Farsi]]. Centuries later, other scripts such as “Pahlavi” and “Avestaee” scripts became popular in ancient Persia. After the rise of [[Islam]] in the seventh century, Persians adapted the Arabic [[alphabet]] to Farsi language and developed the contemporary Farsi alphabet. | ||

== Islamic calligraphy == | == Islamic calligraphy == | ||

{{main | Islamic calligraphy}} | {{main | Islamic calligraphy}} | ||

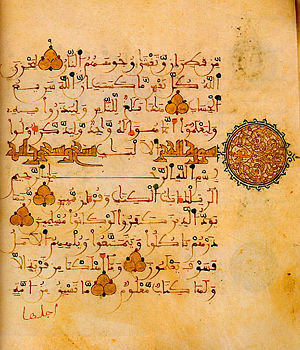

| − | [[Image:AndalusQuran.JPG|thumb|right|300px|A page of a | + | [[Image:AndalusQuran.JPG|thumb|right|300px|A page of a twelfth century [[Qur'an]] written in the [[al-Andalus|Andalusi]] script.]] |

Islamic calligraphy is an aspect of Islamic art that has evolved alongside the religion of [[Islam]] and the [[Arabic language]]. | Islamic calligraphy is an aspect of Islamic art that has evolved alongside the religion of [[Islam]] and the [[Arabic language]]. | ||

| − | [[Arab|Arabic]] and Persian calligraphy | + | [[Arab|Arabic]] and Persian calligraphy are both associated with geometric Islamic art (known as [[arabesque]]) which is found on the walls and ceilings of [[mosque]]s as well as on [[paper]]. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world draw on their calligraphic heritage by using inscriptions or abstractions in their work. |

| − | + | Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The holy book of Islam, [[al-Qur'an]] has played an important role in the development and evolution of the [[Arabic language]], and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. [[Proverb]]s and complete passages from the Qur'an are still sources for Islamic calligraphy. | |

| − | + | Islamic Calligraphy has been an art form especially valued by Muslims who traditionally believed that only [[Allah]] could create images of people and [[animal|animals]] and that figures of such should not be represented in artwork.<ref>[http://www.religionfacts.com/islam/things/depictions-of-muhammad-in-islamic-art.htm Islamic Figurative Art and Depictions of Muhammad] ''Religionfacts.com.'' Retrieved May 19, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | + | There has existed a strong parallel tradition to that of the Islamic, among [[Aramaic]] and [[Hebrew]] language scholars, seen in such works as the Hebrew illustrated bibles of the ninth and tenth centuries. | |

== Western calligraphy == | == Western calligraphy == | ||

| − | Western calligraphy is the calligraphy of the [[Latin]] writing system, and to a lesser degree the [[Greek alphabet|Greek and Cyrillic]] writing systems. | + | Western calligraphy is the calligraphy of the [[Latin]] writing system, and to a lesser degree the [[Greek alphabet|Greek and Cyrillic]] writing systems. During the [[Middle Ages]], hundreds of thousands of manuscripts were produced: many were illuminated with [[gold]] and fine painting.<ref>Christopher De Hamel, ''A History of Illuminated Manuscripts'' (London: Phaidon Press, 1994, ISBN 0714829498).</ref> |

| − | + | [[Image:Schriftzug Urkunde.jpg|thumb|bottom|400px|Calligraphy of the German word "Urkunde" (deed).]] | |

| − | [[Image:Schriftzug Urkunde.jpg|thumb|bottom|400px|Calligraphy of the German word "Urkunde" (deed)]] | + | [[Christian]] churches promoted the development of writing through the prolific copying of the [[Bible]], particularly the [[New Testament]] and other sacred texts.<ref name=hamel>Christopher De Hamel, ''The Book: A History of the Bible'' (London: Phaidon, 2001, ISBN 0714837741).</ref> [[Monk]]s in the British Isles adapted the late Roman bookhand, 'Uncial', to develop a unique bookhand called "Celtic" or "Insular," meaning "of the islands." The seventh to ninth centuries in [[northern Europe]] were the peak time for [[Celtic]] [[illuminated manuscript]]s, exemplified by the 'Lindisfarne Gospels' and the 'Book of Kells'. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Christian]] churches promoted the development of writing through the prolific copying of the Bible, particularly the New Testament and other sacred texts ( | ||

| − | [[Charlemagne]] helped the spread of beautiful writing by bringing Alcuin, the Abbot of York, to his capital of Aachen. Alcuin undertook a major revision of all styles of script and all texts, developing a new bookhand named after his patron Charlemagne | + | [[Charlemagne]] helped the spread of beautiful writing by bringing [[Alcuin]], the Abbot of York, to his capital of [[Aachen]]. Alcuin undertook a major revision of all styles of script and all texts, developing a new bookhand named after his patron Charlemagne. |

| − | ''Blackletter'' (also known as ''Gothic'') and its variation ''Rotunda'', gradually developed from the Carolingian hand during the | + | ''Blackletter'' (also known as ''Gothic'') and its variation ''Rotunda'', gradually developed from the Carolingian hand during the twelfth century. Over the next three centuries, the scribes in northern Europe used an ever more compressed and spiky form of Gothic. Those in [[Italy]] and [[Spain]] preferred the rounder but still heavy-looking ''Rotunda''. During the fifteenth century, Italian scribes returned to the Roman and Carolingian models of writing and designed the Italic hand, also called ''Chancery cursive'', and ''Roman bookhand''. These three hands—''Gothic'', ''Italic'', and ''Roman bookhand''—became the models for printed letters. [[Johannes Gutenberg]] used Gothic to print his famous [[Bible]], but the lighter-weight Italic and Roman bookhand have since become the standard. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Resurgence of Western Calligraphy=== | === Resurgence of Western Calligraphy=== | ||

| − | Hand-written and hand-decorated books largely stopped being produced by about 1510, after printing became ubiquitous | + | Hand-written and hand-decorated books largely stopped being produced by about 1510, after printing became ubiquitous.<ref name=hamel/> However, at the end of the nineteenth century, [[William Morris]] and the [[Arts and Crafts Movement]] redefined, revived, and popularized English broad-pen calligraphy. Morris influenced many calligraphers, including Englishmen [[Edward Johnston]] and [[Eric Gill]].<ref>S. Cockerell (1945), from "Tributes to Edward Johnston" in H. Child and J. Howes, (eds.), ''Lessons in Formal Writing'' (1986), 21-30.</ref> Edward Johnston developed his own broad-edged hand after studying tenth-century manuscripts. |

| − | + | Johnston, author of ''Writing, Illuminating & Lettering'' (1906) initially taught his students an uncial hand using a flat pen angle, but later changed to teaching students his “foundational hand” using a slanted pen angle. He first referred to this hand as “Foundational Hand” in his 1909 publication, ''Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For schools and classes and for the use of craftsmen''.<ref>Edward Johnston, ''Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For Schools & Classes & for the Use of Craftsmen'' (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1928, OCLC: 16851305), plate 6.</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Copperplate=== | |

| + | Copperplate is a style of calligraphic writing written with a sharp pointed nib instead of the broad-edged nib used in most calligraphic writing. The name comes from the sharp lines of the writing style resembling the etches of engraved [[copper]]. The Copperplate typeface attempts to emulate copper-engraved letters. | ||

| − | + | Copperplate obtains its name from the copybooks of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which were created by the engraving of copper printing plates using a transferred ink original. Students worked diligently to copy these works, although an exact replica could never be obtained, because the works were created originally from the chiseling of copper plates. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Tools == | |

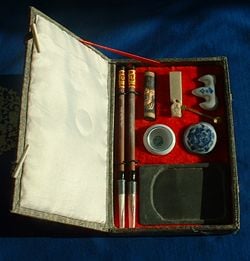

| + | [[Image:WenfangSibao.jpg|thumb|250px|left|The tools of a Chinese Calligrapher]] | ||

| + | The principal tools for a calligrapher are the [[pen]], which may be flat- or round-nibbed and the [[paint brush|brush]]. For certain decorative purposes, multi-nibbed pens—steel brushes—can be used. However, works have also been made with felt-tip pen and ballpoint pens, although these works do not employ angled lines. [[Ink]] for writing is usually water-based and much less viscous than the [[oil based ink]]s used in [[printing]]. High quality paper, which has good porousness, will enable cleaner lines, although parchment or ''vellum'' is often used, as a knife can be used to erase work on them and a [[light box]] is not needed to allow lines to pass through it. In addition, light boxes and templates are often used in order to achieve straight lines without pencil markings detracting from the work. Lined paper, either for a light box or direct use, is most often lined every quarter or half inch, although inch spaces are occasionally used, such as with ''litterea unciales'', and college ruled paper acts as a guideline often as well. | ||

===Calligraphy Today=== | ===Calligraphy Today=== | ||

| − | Calligraphy continues to be used today in graphic design, logo design, maps, menus, greeting cards, invitations, legal documents, diplomas, poetry, business cards and handmade presentations. Many calligraphers find their "bread and butter" work in the addressing of calligraphic envelopes and invitations for | + | Calligraphy continues to be used today in graphic design, logo design, maps, menus, greeting cards, invitations, legal documents, diplomas, [[poetry]], business cards and handmade presentations. Many calligraphers find their "bread and butter" work in the addressing of calligraphic envelopes and invitations for [[wedding]]s and large parties. The digital era has facilitated the creation and dissemination of new and historically related fonts; thousands are now in use. Calligraphy itself gives unique expression to every individual letterform, not possible with typeface technologies no matter their sophistication.<ref>George Thomson, ''Digital Calligraphy with Photoshop'' (Cambridge, Mass: Course Technology, 2004, ISBN 1592004989).</ref> |

| − | The calligraphic art is | + | The calligraphic art is no longer just about literal reproduction of historic and religious text. Written forms have become more [[abstract art|abstract]] and are incorporated into works which have as much resonance with contemporary painting as they do with ancient manuscript writing. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | In 1998 British calligrapher [[Donald Jackson]] was commissioned, by [[Saint John's University]] to hand illuminate the ''St. John's Bible'', a project which took him five years to complete. At various stages of completion books from the Bible have been seen on display at the Minneapolis Art Institute, and in 2006 ''Illuminating the Word'', the national touring exhibition of The Saint John’s Bible, opened at the [[Library of Congress]] in Washington, D.C.<ref>[http://www.saintjohnsbible.org/why/dream.htm The Saint John's Bible] ''Saintjohnsbible.org.'' Retrieved May 19, 2008.</ref> | ||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Cinamon, | + | *Anderson, Donald M. ''The Art of Written Forms; The Theory and Practice of Calligraphy.'' New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969. ISBN 0030686253 |

| − | + | *Cinamon, Gerald. ''Rudolf Koch: Letterer, Type Designer, Teacher''. New Castle, Del: Oak Knoll Press, 2000. ISBN 1584560134 | |

| − | * | + | *De Hamel, Christopher. ''The Book: A History of the Bible'' London: Phaidon, 2001. ISBN 0714837741 |

| − | * | + | *De Hamel, Christopher. ''A History of Illuminated Manuscripts''. London: Phaidon Press, 1994. ISBN 0714829498 |

| − | + | *Cennini, Cennino, and Christiania Jane Powell Herringham. ''The Book of the Art of Cennino Cennini: A Contemporary Practical Treatise on Quattrocento Painting.'' London: G. Allen & Unwin, ltd, 1899. OCLC 6441291 | |

| − | *Herringham | + | *Hewitt, Graily. ''Lettering for Students & Craftsmen.'' New York: Taplinger Pub. Co, 1981. ISBN 0800847288 |

| − | *Hewitt, | + | *Jackson, Donald. ''The Story of Writing.'' New York, N.Y.: Taplinger Pub. Co, 1981. ISBN 0800801725 |

| − | *Jackson, | + | *Johnston, Edward. ''Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering.'' London: Pitman, 1977. ISBN 0273010646 |

| − | *Johnston, | + | *Lovett, Patricia. ''Calligraphy & Illumination: A History and Practical Guide.'' New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000. ISBN 0810941198 |

| − | * | + | *Neugebauer, Friedrich. ''The Mystic Art of Written Forms: An Illustrated Handbook of Lettering.'' Salzburg: Neugebauer Press, 1980. ISBN 0907234003 |

| − | + | *Thomson, George. ''Digital Calligraphy with Photoshop.'' Cambridge, Mass: Course Technology, 2004. ISBN 1592004989 | |

| − | + | *Zapf, Hermann, Gudrun Zapf von Hesse, and John Prestianni. ''Calligraphic Type Design in the Digital Age: An Exhibition in Honor of the Contributions of Hermann and Gudrun Zapf: Selected Type Designs and Calligraphy by Sixteen Designers.'' Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2001. ISBN 1584230967 | |

| − | |||

| − | *Neugebauer, | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *Thomson, | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | *[http:// | + | All links retrieved November 25, 2023. |

| − | *[http://www. | + | |

| − | *[http://www.islamicity.com/Culture/Calligraphy/default.HTM Islamic calligraphy] | + | *[http://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/callig/callmain.htm Calligraphy] ''Depts.washington.edu.'' |

| − | *[http://international.loc.gov/intldl/apochtml/apochome.html | + | *[http://www.ehow.com/videos-on_4387_do-calligraphy.html How to do Calligraphy] ''eHow.com.'' |

| − | + | *Mamoun Sakkal. 1993. [http://sakkal.com/ArtArabicCalligraphy.html The Art of Arabic Calligraphy] ''Sakal.com.'' | |

| − | *[http://www. | + | *[http://www.islamicity.com/Culture/Calligraphy/default.HTM Islamic calligraphy] ''Islamicity.com.'' |

| − | + | *[http://international.loc.gov/intldl/apochtml/apochome.html Selections of Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Calligraphy] ''International.loc.gov.'' | |

| − | *[http://www.ejf.org.uk The Edward Johnston Foundation] | + | *[http://www.theartofcalligraphy.com/shodo.html Contemporary Buddhist Calligraphy] ''Theartofcalligraphy.com'' |

| − | *[http://www. | + | *[http://www.ejf.org.uk The Edward Johnston Foundation] ''Ejf.org.uk'' |

| − | + | *[http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00xcallig/modern/zakariya/zakariya.html American calligrapher Muhammad Zakariya] ''Columbia.edu'' | |

| − | *[http://www.script-sign.com | + | *[http://www.script-sign.com Michel D'Anastasio and Hebraic Calligraphy] ''Script-sign.com'' |

| + | |||

| + | {{Credit|213077918}} | ||

[[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:29, 25 November 2023

Calligraphy (from the Greek meaning κάλλος kallos "beauty" + γραφή graphẽ "writing") is a form of ornamental handwriting found in various cultures throughout the world and whose origins date back to ancient times. A contemporary definition of calligraphic practice would be: "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious and skillful manner."[1]

Calligraphic works range from functional inscriptions and hand lettering to fine art pieces where the artistic manifestation may take precedence over the legibility of the letters. Well-crafted calligraphy differs from typography and non-classical hand-lettering in that characters are disciplined yet fluid and spontaneous. Often they are improvised at the moment of writing.

Calligraphy has played a significant role in the history of many cultures and their languages. Muslims were among those who valued calligraphy not only as art but also used it as the ultimate expression of God’s words.[2] Ancient and holy books of many religions have been handwritten in illuminated calligraphic script. In present times, calligraphy continues to flourish in the form of wedding and event invitations, typography, original hand-lettered logo design, commissioned calligraphic art, maps, and other works involving writing.

Twentieth century calligraphy master, Edward Johnston, best described the process of writing calligraphy when he advised: "All rules must give way to Truth and Freedom."[3]

East Asian calligraphy

Calligraphy is considered an important art in East Asia and as the most refined form of East Asian painting. It has influenced most major art styles, including 'sumi-e', a style of Chinese and Japanese ink and wash painting which uses similar tools and techniques and is based entirely on calligraphy.

East Asian calligraphy typically uses ink brushes to write Chinese characters which are called by various names: 'Hanzi' in Chinese, 'Kanji' in Japanese, and 'Hanja' in Korean and Hán Tự in Vietnamese. The term calligraphy: in Chinese, Shufa 書法, in Japanese Shodō 書道, in Korean, Seoye 書藝, all mean 'the way of writing'.

| The main categories of Chinese-character calligraphy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English name | Hanzi (Pinyin) | Hangul (RR) | Rōmaji | Quốc ngữ |

| Seal script | 篆書(Zhuànshū) | 전서(Jeonseo) | Tensho | Triện thư |

| Clerical script (Official script) | 隸書 (隷書)(Lìshū) |

예서(Yeseo) | Reisho | Lệ thư |

| Regular Script (Block script) | 楷書(Kǎishū) | 해서(Haeseo) | Kaisho | Khải thư |

| Running script (Semi-cursive Script) | 行書(Xíngshū) | 행서(Haengseo) | Gyōsho | Hành thư |

| Grass script (Cursive script) | 草書(Cǎoshū) | 초서(Choseo) | Sōsho | Thảo thư |

Indian Calligraphy

Persian and Arabic script is thought to have influenced Indian calligraphy, although the scripts used are somewhat different. The flowing Persian script was thought to have influenced the writing style of Indian epics. Calligraphy in India was especially influenced by Sikhism whose holy book has been traditionally handwritten and illuminated. In ancient times the lack of modern printing technology resulted in a rich heritage of calligraphy in many Indian languages.

Nepalese calligraphy

Nepalese calligraphy has a huge impact on Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Ranjana script is the primary form of this calligraphy.

It is primarily used for writing Nepal Bhasa but is also used in monasteries of India, Tibet, coastline China, Mongolia, and Japan.[5] In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist traditions, it is famously used to write various mantras including the Om mane padme hum mantra of Aryawalokirteshwar, the Mantra of Arya Tara Om tare tuttare ture svaha, and the mantra of Manjushree Om ara pa cana dhi. The script is also used in Hindu scriptures.

In Tibet, the script is called Lantsa and used to write the original texts of Sanskrit.

Tibetan Calligraphy

Calligraphy is central to Tibetan culture. The script is derived from Indic scripts. As in China, the nobles of Tibet, such as the High Lamas and oracles of the Potala Palace, were usually skilled calligraphers. For several centuries, Tibet has been a center of Buddhism, a religion that places a great deal of significance on the written word. Almost all high religious writing involved calligraphy, including letters sent by the Dalai Lama and other religious, and secular, figures of authority. Calligraphy is particularly evident on their prayer wheels, although this calligraphy was forged rather than scribed, much like Arab and Roman calligraphy is often found on buildings. Although originally done with a brush, Tibetan calligraphers now use chisel tipped pens and markers.

Persian calligraphy

History of Persian Calligraphy

The history of calligraphy in Persia dates back to the pre-Islam era. In Zoroastrianism, beautiful and clear writings were highly valued.[6] The three main forms of Persian calligraphy are called: Nasta'liq script, Shekasteh-Nasta'liq script and Naghashi-khat script. “Nasta'liq” is the most popular contemporary style among classical Persian calligraphy scripts and Persian calligraphers call it the “Bride of the Calligraphy Scripts.” This calligraphy style has been based on rigid structure that has changed very little over the years.

It is believed that ancient Persian script was invented by about 500-600 B.C.E. to provide monument inscriptions for the Achaemenid kings. These scripts consisted of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal nail-shape letters—the reason it is called “Script of Nails” (Khat-e-Mikhi) in Farsi. Centuries later, other scripts such as “Pahlavi” and “Avestaee” scripts became popular in ancient Persia. After the rise of Islam in the seventh century, Persians adapted the Arabic alphabet to Farsi language and developed the contemporary Farsi alphabet.

Islamic calligraphy

Islamic calligraphy is an aspect of Islamic art that has evolved alongside the religion of Islam and the Arabic language.

Arabic and Persian calligraphy are both associated with geometric Islamic art (known as arabesque) which is found on the walls and ceilings of mosques as well as on paper. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world draw on their calligraphic heritage by using inscriptions or abstractions in their work.

Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The holy book of Islam, al-Qur'an has played an important role in the development and evolution of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and complete passages from the Qur'an are still sources for Islamic calligraphy.

Islamic Calligraphy has been an art form especially valued by Muslims who traditionally believed that only Allah could create images of people and animals and that figures of such should not be represented in artwork.[7]

There has existed a strong parallel tradition to that of the Islamic, among Aramaic and Hebrew language scholars, seen in such works as the Hebrew illustrated bibles of the ninth and tenth centuries.

Western calligraphy

Western calligraphy is the calligraphy of the Latin writing system, and to a lesser degree the Greek and Cyrillic writing systems. During the Middle Ages, hundreds of thousands of manuscripts were produced: many were illuminated with gold and fine painting.[8]

Christian churches promoted the development of writing through the prolific copying of the Bible, particularly the New Testament and other sacred texts.[9] Monks in the British Isles adapted the late Roman bookhand, 'Uncial', to develop a unique bookhand called "Celtic" or "Insular," meaning "of the islands." The seventh to ninth centuries in northern Europe were the peak time for Celtic illuminated manuscripts, exemplified by the 'Lindisfarne Gospels' and the 'Book of Kells'.

Charlemagne helped the spread of beautiful writing by bringing Alcuin, the Abbot of York, to his capital of Aachen. Alcuin undertook a major revision of all styles of script and all texts, developing a new bookhand named after his patron Charlemagne.

Blackletter (also known as Gothic) and its variation Rotunda, gradually developed from the Carolingian hand during the twelfth century. Over the next three centuries, the scribes in northern Europe used an ever more compressed and spiky form of Gothic. Those in Italy and Spain preferred the rounder but still heavy-looking Rotunda. During the fifteenth century, Italian scribes returned to the Roman and Carolingian models of writing and designed the Italic hand, also called Chancery cursive, and Roman bookhand. These three hands—Gothic, Italic, and Roman bookhand—became the models for printed letters. Johannes Gutenberg used Gothic to print his famous Bible, but the lighter-weight Italic and Roman bookhand have since become the standard.

Resurgence of Western Calligraphy

Hand-written and hand-decorated books largely stopped being produced by about 1510, after printing became ubiquitous.[9] However, at the end of the nineteenth century, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement redefined, revived, and popularized English broad-pen calligraphy. Morris influenced many calligraphers, including Englishmen Edward Johnston and Eric Gill.[10] Edward Johnston developed his own broad-edged hand after studying tenth-century manuscripts.

Johnston, author of Writing, Illuminating & Lettering (1906) initially taught his students an uncial hand using a flat pen angle, but later changed to teaching students his “foundational hand” using a slanted pen angle. He first referred to this hand as “Foundational Hand” in his 1909 publication, Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For schools and classes and for the use of craftsmen.[11]

Copperplate

Copperplate is a style of calligraphic writing written with a sharp pointed nib instead of the broad-edged nib used in most calligraphic writing. The name comes from the sharp lines of the writing style resembling the etches of engraved copper. The Copperplate typeface attempts to emulate copper-engraved letters.

Copperplate obtains its name from the copybooks of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which were created by the engraving of copper printing plates using a transferred ink original. Students worked diligently to copy these works, although an exact replica could never be obtained, because the works were created originally from the chiseling of copper plates.

Tools

The principal tools for a calligrapher are the pen, which may be flat- or round-nibbed and the brush. For certain decorative purposes, multi-nibbed pens—steel brushes—can be used. However, works have also been made with felt-tip pen and ballpoint pens, although these works do not employ angled lines. Ink for writing is usually water-based and much less viscous than the oil based inks used in printing. High quality paper, which has good porousness, will enable cleaner lines, although parchment or vellum is often used, as a knife can be used to erase work on them and a light box is not needed to allow lines to pass through it. In addition, light boxes and templates are often used in order to achieve straight lines without pencil markings detracting from the work. Lined paper, either for a light box or direct use, is most often lined every quarter or half inch, although inch spaces are occasionally used, such as with litterea unciales, and college ruled paper acts as a guideline often as well.

Calligraphy Today

Calligraphy continues to be used today in graphic design, logo design, maps, menus, greeting cards, invitations, legal documents, diplomas, poetry, business cards and handmade presentations. Many calligraphers find their "bread and butter" work in the addressing of calligraphic envelopes and invitations for weddings and large parties. The digital era has facilitated the creation and dissemination of new and historically related fonts; thousands are now in use. Calligraphy itself gives unique expression to every individual letterform, not possible with typeface technologies no matter their sophistication.[12]

The calligraphic art is no longer just about literal reproduction of historic and religious text. Written forms have become more abstract and are incorporated into works which have as much resonance with contemporary painting as they do with ancient manuscript writing.

In 1998 British calligrapher Donald Jackson was commissioned, by Saint John's University to hand illuminate the St. John's Bible, a project which took him five years to complete. At various stages of completion books from the Bible have been seen on display at the Minneapolis Art Institute, and in 2006 Illuminating the Word, the national touring exhibition of The Saint John’s Bible, opened at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Claude Mediavilla, Alan Marshall, Mark Van Stone, Gerard Xuriguera, and Donald Jackson, Calligraphy: From Calligraphy to Abstract Painting. (Wommelgem, Belgium: Scirpus Publications, 1996, ISBN 9080332518), 18.

- ↑ Islamic Calligraphy Islamicarchitecture.org. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ↑ Edward Johnston, Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering (London: Pitman, 1977, ISBN 0273010646).

- ↑ Calligraphy by Denis Brown Quillskill.com. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Nepal Lipi - The Nepalese Scripts Jwajalapa.com.

- ↑ Persian Alphabet Stanford.edu. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ↑ Islamic Figurative Art and Depictions of Muhammad Religionfacts.com. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ↑ Christopher De Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts (London: Phaidon Press, 1994, ISBN 0714829498).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Christopher De Hamel, The Book: A History of the Bible (London: Phaidon, 2001, ISBN 0714837741).

- ↑ S. Cockerell (1945), from "Tributes to Edward Johnston" in H. Child and J. Howes, (eds.), Lessons in Formal Writing (1986), 21-30.

- ↑ Edward Johnston, Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For Schools & Classes & for the Use of Craftsmen (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1928, OCLC: 16851305), plate 6.

- ↑ George Thomson, Digital Calligraphy with Photoshop (Cambridge, Mass: Course Technology, 2004, ISBN 1592004989).

- ↑ The Saint John's Bible Saintjohnsbible.org. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Donald M. The Art of Written Forms; The Theory and Practice of Calligraphy. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969. ISBN 0030686253

- Cinamon, Gerald. Rudolf Koch: Letterer, Type Designer, Teacher. New Castle, Del: Oak Knoll Press, 2000. ISBN 1584560134

- De Hamel, Christopher. The Book: A History of the Bible London: Phaidon, 2001. ISBN 0714837741

- De Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. London: Phaidon Press, 1994. ISBN 0714829498

- Cennini, Cennino, and Christiania Jane Powell Herringham. The Book of the Art of Cennino Cennini: A Contemporary Practical Treatise on Quattrocento Painting. London: G. Allen & Unwin, ltd, 1899. OCLC 6441291

- Hewitt, Graily. Lettering for Students & Craftsmen. New York: Taplinger Pub. Co, 1981. ISBN 0800847288

- Jackson, Donald. The Story of Writing. New York, N.Y.: Taplinger Pub. Co, 1981. ISBN 0800801725

- Johnston, Edward. Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering. London: Pitman, 1977. ISBN 0273010646

- Lovett, Patricia. Calligraphy & Illumination: A History and Practical Guide. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000. ISBN 0810941198

- Neugebauer, Friedrich. The Mystic Art of Written Forms: An Illustrated Handbook of Lettering. Salzburg: Neugebauer Press, 1980. ISBN 0907234003

- Thomson, George. Digital Calligraphy with Photoshop. Cambridge, Mass: Course Technology, 2004. ISBN 1592004989

- Zapf, Hermann, Gudrun Zapf von Hesse, and John Prestianni. Calligraphic Type Design in the Digital Age: An Exhibition in Honor of the Contributions of Hermann and Gudrun Zapf: Selected Type Designs and Calligraphy by Sixteen Designers. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2001. ISBN 1584230967

External links

All links retrieved November 25, 2023.

- Calligraphy Depts.washington.edu.

- How to do Calligraphy eHow.com.

- Mamoun Sakkal. 1993. The Art of Arabic Calligraphy Sakal.com.

- Islamic calligraphy Islamicity.com.

- Selections of Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Calligraphy International.loc.gov.

- Contemporary Buddhist Calligraphy Theartofcalligraphy.com

- The Edward Johnston Foundation Ejf.org.uk

- American calligrapher Muhammad Zakariya Columbia.edu

- Michel D'Anastasio and Hebraic Calligraphy Script-sign.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.