Difference between revisions of "Biblical Inerrancy" - New World Encyclopedia

| (27 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | '''Biblical inerrancy''' is the doctrinal position | + | [[Image:The Evangelist Matthew Inspired by an Angel.jpg|thumb|200px|Rembrandt's version of an angel whispering into the ear of the Evangelist Matthew]] |

| + | '''Biblical inerrancy''' is the doctrinal position that in its original form, the [[Bible]] is totally without error, and free from all contradiction; referring to the complete accuracy of Scripture, including the historical and scientific parts. Inerrancy is distinguished from [[biblical infallibility]] (or limited inerrancy), which holds that the Bible is inerrant on issues of faith and practice but not history or science. | ||

| − | + | Those adhering to biblical inerrancy usually admit the possibility of errors in translation of [[sacred text]]. A famous quote from [[St. Augustine]] declares, "It is not allowable to say, 'The author of this book is mistaken;' but either the manuscript is faulty, or the translation is wrong, or you have not understood.” | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Inerrancy has come under strong criticism in the modern era. Although several Protestant groups do adhere to it, the [[Catholic Church]] no longer strictly upholds the doctrine. Many contemporary Christians, while holding to basic moral and theological truths of the [[Bible]], cannot in good conscience accept its primitive cosmological outlook, or—on close reading—the the troubling ethical attitudes of some its writers. | ||

==Inerrancy in context== | ==Inerrancy in context== | ||

| + | [[File:Paul in prison by Rembrandt.jpg|thumb|200px|Saint Paul, the supposed author of 2 Timothy, said that "all scripture is God-breathed." However, the New Testament had not yet been written in Paul's day.]] | ||

Many denominations believe that the [[Bible]] is [[biblical inspiration|inspired]] by [[God]], who through the human authors is the divine author of the Bible. | Many denominations believe that the [[Bible]] is [[biblical inspiration|inspired]] by [[God]], who through the human authors is the divine author of the Bible. | ||

| − | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness | + | This is expressed in the following Bible passage: "All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness [[2 Timothy]] 3:16 [[NIV]]).</blockquote> |

| − | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Although the author here refers to the [[Hebrew Scripture]] and not the Christian [[New Testament]], which had not been compiled or completely written at the time of [[2 Timothy]]'s writing, most Christians take this saying to apply to the New Testament canon, which came to be accepted in the early fourth century C.E. | |

| − | Many | + | Many who believe in the ''inspiration'' of scripture teach that it is ''[[biblical infallibility|infallible]].'' However, those who accept the infallibility of scripture hold that its historical or scientific details, which may be irrelevant to matters of faith and Christian practice, may contain errors. Those who believe in ''inerrancy,'' however, hold that the scientific, geographic, and historic details of the scriptural texts in their original manuscripts are completely true and without error. On the other hand, a number of contemporary Christians have come to question even the doctrine of infallibility, holding that the biblical writers were indeed inspired at time by God, but that they also express their own, all too human attitudes. In this view, it is ultimately up to the individual conscience to decide what parts of the Bible are truly inspired and accurate, and what parts are the expression of human fallibility. Indeed, much of biblical scholarship in the last two centuries has taken the position that the Bible must be studied in its historical context as a human work, and not only as a sacred scripture which must not be questioned or contradicted by historical or scientific facts. |

| − | |||

| − | On the other hand, the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The theological basis of the belief of inerrancy, in its simplest form, is that as [[God]] is perfect, the [[Bible]], as the word of God, must also be perfect, thus, free from error. | ||

Proponents of biblical inerrancy also teach that God used the "distinctive personalities and literary styles of the writers" of scripture but that God's inspiration guided them to flawlessly project his message through their own language and personality. | Proponents of biblical inerrancy also teach that God used the "distinctive personalities and literary styles of the writers" of scripture but that God's inspiration guided them to flawlessly project his message through their own language and personality. | ||

| − | Infallibility and inerrancy refer to the original texts of the Bible. And while conservative scholars acknowledge the potential for human error in transmission and translation, modern translations are considered to "faithfully represent the originals".<ref>http://www. | + | Infallibility and inerrancy refer to the original texts of the Bible. And while conservative scholars acknowledge the potential for human error in transmission and translation, modern translations are considered to "faithfully represent the originals".<ref>[http://www.bible-researcher.com/chicago1.html Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy with Exposition] ''Bible Research''. Retrieved September 26, 2018.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In their text on the subject, Geisler and Nix (1986) claim that scriptural inerrancy is established by a number of observations and processes,<ref>Norman Geisler and William E. Nix, ''A General Introduction to the Bible'' (Moody Publishers, 1986, ISBN 0802429165).</ref> which include: | |

| − | + | * The historical accuracy of the Bible | |

| − | + | * The Bible's claims of its own inerrancy | |

| − | + | * Church history and tradition | |

| − | + | * One's individual experience with God | |

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

==Major religious views on the Bible== | ==Major religious views on the Bible== | ||

===Roman Catholics=== | ===Roman Catholics=== | ||

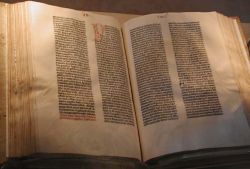

| − | [[ | + | [[Image:Gutenberg Bible.jpg|thumb|250px|A copy of the [[Gutenberg Bible]], in the Latin Vulgate]] |

| − | + | [[Roman Catholic Church]] teaching on the question of inerrancy has evolved considerably in the last century. Speaking from the claimed authority granted to him by Christ, Pope [[Pius XII]], in his encyclical ''[[Divino Afflante Spiritu]],'' denounced those who held that the inerrancy was restricted to matters of faith and morals. He reaffirmed the decision of the Council of Trent that the Vulgate Latin edition of the Bible is both sacred and canonical and stated that these "entire books with all their parts" are free "from any error whatsoever." He officially criticized those Catholic writers who wished to restrict the authority of scripture "to matters of faith and morals" as being "in error." | |

| − | + | However, ''[[Dei Verbum]]'', one of the principal documents of the [[Second Vatican Council]] hedges somewhat on this issue. This document states the Catholic belief that all scripture is sacred and reliable because the biblical authors were inspired by God. However, the human dimension of the Bible is also acknowledged as well as the importance of proper interpretation. Careful attention must be paid to the actual meaning intended by the authors, in order to render a correct interpretation. Genre, modes of expression, historical circumstances, poetic liberty, and church tradition are all factors that must be considered by Catholics when examining scripture. | |

| + | |||

| + | The Roman Catholic Church further holds that the authority to declare correct interpretation rests ultimately with the Church. | ||

===Eastern Orthodox Christians=== | ===Eastern Orthodox Christians=== | ||

| − | + | Because the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] emphasizes the authority of councils, which belong to all the bishops, it stresses the canonical uses more than inspiration of scripture. The Eastern Orthodox Church thus believes in unwritten tradition and the written scriptures. Contemporary Eastern Orthodox theologians debate whether these are separate deposits of knowledge or different ways of understanding a single dogmatic reality. | |

| − | + | The Eastern Orthodox Church also emphasizes that the scriptures can only be understood according to a normative rule of faith (the [[Nicene Creed|Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed]]) and the way of life that has continued from Christ to this day. | |

| − | ===Protestant views | + | ===Conservative Protestant views=== |

| − | + | In 1978, a large gathering of American [[Protestant]] churches, including representatives of the Conservative, [[Reformed Church in America|Reformed]] and [[Presbyterian]], [[Lutheran]], and [[Baptist]] denominations, adopted the ''[[Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy]]''. The Chicago Statement does not imply that any particular traditional translation of the Bible is without error. Instead, it gives primacy to seeking the intention of the author of each original text, and commits itself to receiving the statement as fact depending on whether it can be determined or assumed that the author meant to communicate a statement of fact. Of course, knowing the intent of the original authors is impossible. | |

| − | In 1978, a large gathering of American [[Protestant]] churches, including representatives of the Conservative, [[Reformed Church in America|Reformed]] and [[Presbyterian]], [[Lutheran]], and [[Baptist]] denominations, adopted the [[Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy]]. The Chicago Statement does not imply that any particular traditional translation of the Bible is without error. Instead, it gives primacy to seeking the intention of the author of each original text, and commits itself to receiving the statement as fact depending on whether it can be determined or assumed that the author meant to communicate a statement of fact. Of course, knowing the intent of the original authors is impossible. | ||

| − | Acknowledging that there are many kinds of literature in the Bible besides statements of fact, the Statement nevertheless reasserts the authenticity of the Bible ''in toto'' as the word of God. Advocates of the Chicago Statement are worried that accepting one error in the Bible leads one down a slippery slope that ends in rejecting that the Bible has any value greater than some other book | + | [[Image:Frontpiece Cambridge.jpg|thumb|Title page of the King James Version]] |

| + | Acknowledging that there are many kinds of literature in the Bible besides statements of fact, the Statement nevertheless reasserts the authenticity of the Bible ''in toto'' as the word of God. Advocates of the Chicago Statement are worried that accepting one error in the Bible leads one down a slippery slope that ends in rejecting that the Bible has any value greater than some other book" <blockquote>"The authority of Scripture is inescapably impaired if this total divine inerrancy is in any way limited or disregarded, or made relative to a view of truth contrary to the Bible's own; and such lapses bring serious loss to both the individual and the church."<ref> [http://www.alliancenet.org/the-chicago-statement-on-biblical-inerrancy The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy] Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals. Retrieved September 26, 2018.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | However, this view is not accepted as normative by many mainline denominations, including many churches and ministers who adopted the Statement. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====King James Only==== | ====King James Only==== | ||

| − | Another belief, [[King James Only]], holds that the translators of the [[King James Version]] English Bible were guided by God, and that the KJV | + | Another belief, [[King James Only]], holds that the translators of the ''[[King James Version]]'' English Bible were guided by God, and that the KJV is to be taken as the authoritative English Bible. Modern translations differ from the KJV on numerous points, sometimes resulting from access to different early texts, largely as a result of work in the field of [[Textual Criticism]]. Upholders of the KJV-Only view nevertheless hold that the [[Protestant]] canon of the KJV is itself an inspired text and therefore remains authoritative. The King James Only movement asserts that the KJV is the ''sole'' [[English language|English]] translation free from error. |

| − | ====Textus Receptus | + | ====Textus Receptus==== |

| − | Similar to the King James Only view is the view that | + | Similar to the King James Only view is the view that translations must be derived from the ''[[Textus Receptus]]''—the name given to the printed Greek texts of the New Testament used by both [[Martin Luther]] and the KJV translators—in order to be considered inerrant. For example, in Spanish-speaking cultures the commonly accepted "KJV-equivalent" is the [[Reina-Valera]] 1909 revision (with different groups accepting it in addition to the 1909, or in its place the revisions of 1862 or 1960). |

====Wesleyan and Methodist view of scripture==== | ====Wesleyan and Methodist view of scripture==== | ||

| − | The [[John Wesley|Wesleyan]] and [[Methodist]] Christian tradition affirms that the Bible is authoritative on matters concerning faith and practice | + | The [[John Wesley|Wesleyan]] and [[Methodist]] Christian tradition affirms that the Bible is authoritative on matters concerning faith and practice but does not use the word "inerrant" to describe the Bible. What is of central importance for the Wesleyan Christian tradition is the Bible as a tool which God uses to promote salvation. According to this tradition, the Bible does not itself effect salvation; God initiates salvation and proper creaturely responses consummate salvation. One may be in danger of [[bibliolatry]] if one claims that the Bible secures salvation. |

| − | + | ====Lutheran views==== | |

| + | The larger [[Evangelical Lutheran Church in America]] and [[Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada]] do not officially hold to biblical inerrancy. | ||

| − | + | The [[Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod]], the [[Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod]], the [[Lutheran Church--Canada]], the [[Evangelical Lutheran Synod]], and many other smaller Lutheran bodies do hold to scriptural inerrancy, though for the most part Lutherans do not consider themselves to be "fundamentalists." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The [[Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod]], the [[Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod]], the [[Lutheran Church - Canada]], the [[Evangelical Lutheran Synod]], and many other smaller Lutheran bodies hold to | ||

==Criticisms of biblical inerrancy== | ==Criticisms of biblical inerrancy== | ||

| − | Proponents of biblical inerrancy | + | Proponents of biblical inerrancy refer to {{bibleverse|2|Timothy|3:16|9}}—"all scripture is given by inspiration of God"—as evidence that the whole Bible is inerrant. However, critics of this doctrine think that the Bible makes no direct claim to be inerrant or infallible. Indeed, in context, this passage refers only to the [[Old Testament]] writings understood to be scripture at the time it was written. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The idea that the Bible contains no mistakes is mainly justified by appeal to proof-texts that refer to its divine inspiration. However, this argument has been criticized as circular reasoning, because these statements only have to be accepted as true if the Bible is already thought to be inerrant. Moreover, no biblical text says that because a text is inspired, it is therefore always correct in its historical or even its moral statements. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Falsifiability=== | ===Falsifiability=== | ||

| − | Biblical inerrancy has also been criticized on the grounds that many statements about [[history]] or [[science]] that are found in Scripture may be demonstrated to be untenable. Inerrancy is argued to be a [[Modus tollens| falsifiable]] proposition: | + | Biblical inerrancy has also been criticized on the grounds that many statements about [[history]] or [[science]] that are found in Scripture may be demonstrated to be untenable. Inerrancy is argued to be a [[Modus tollens|falsifiable]] proposition: If the Bible is found to contain any mistakes or [[Internal consistency of the Bible|contradictions]], the proposition has been refuted. Opinion is divided over which parts of the Bible are trustworthy in the light of these considerations. Critical theologians answer that the Bible contains at least two divergent views of the nature of God: A bloody tribal deity and a loving father. The choice of which viewpoint to value can be based on that which is found to be intellectually coherent and morally challenging, and this is given priority over other teachings found in books of the Bible. |

| − | ===Mythical cosmology, a | + | ===Mythical cosmology, a stumbling-block=== |

| − | The | + | [[File:Cavallino St. John the Evangelist.jpg|thumb|200px|The ideal of dozens of biblical writers, such as the Apostle John, each writing under the inspiration of the [[Holy Spirit]] to produce a perfectly inerrant collection of scriptures no longer finds credibility among many modern readers of scripture.]] |

| − | + | The Bible encapsulates a different world-view from the one shared by most people who live in the world now. In the gospels there are [[demon]]s and possessed people: There is a heaven where God sits and an underworld, where go the dead. Evidence suggests that the cosmology of the Bible assumed that the Earth was flat and that the sun traveled around the Earth, and that the Earth was created in six days within the last 10,000 years. | |

| − | + | Christian fundamentalists who advance the doctrine of inerrancy use the supernatural as a means of explanation for miraculous stories from the Bible. An example is the story of [[Jonah]]. Jonah 1:15-17 tells how on making a voyage to Tarshish, a storm threatened the survival of the boat, and to calm the storm the sailors: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>… took Jonah and threw him overboard, and the raging sea grew calm. At this the men greatly feared the Lord, and they offered a sacrifice to the Lord and made vows to him. But the Lord prepared a great fish to swallow Jonah, and Jonah was inside the fish three days and three nights.</blockquote> | |

| − | [[Bernard Ramm]] explained the miracle of Jonah's sojourn within the great fish or whale as an act of special creation.<ref>Ramm | + | [[Bernard Ramm]] explained the miracle of Jonah's sojourn within the great fish or whale as an act of special creation.<ref>Bernard Ramm, ''The Christian View of Science and Scripture'' (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1954, ISBN 978-0802814296).</ref> Critics of this view sarcastically ask whether it had a primitive form of air-conditioning for the well-being of the [[prophet]] and a writing-desk with inkpot and pen so that the prophet could compose the prayer which is recorded in Jonah 2. Inerrancy means believing that this mythological cosmology and such stories are 100 percent truthful.<ref>Ian Plimer, ''Telling Lies for God: Reason vs Creationism'' (Random House, 1994).</ref> |

| − | + | Even more disturbing to some readers are the moral implications of accepting the biblical claim that God commanded the the slaughter of women and children (Numbers 31:17), and even the [[genocide]] of rival ethnic groups (1 Samuel 15:3). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The leading twentieth century biblical scholar and theologian [[Rudolf Bultmann]] thought that modern people could not accept such propositions in good conscience, and that this understanding of scripture literally could become a stumbling-block to faith.<ref>Rudolf Bultmann, ''Jesus Christ and Mythology'' (Pearson, 1981, ISBN 978-0023055706).</ref> For Bultmann and his followers, the answer was the demythologization of the Christian message, together with a critical approach to biblical studies. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Boone, Kathleen C. ''The Bible Tells Them So: The Discourse of Protestant Fundamentalism'' | + | * Boone, Kathleen C. ''The Bible Tells Them So: The Discourse of Protestant Fundamentalism''. State University of New York Press, 1989. ISBN 0887068952 |

| − | *Ehrman, Bart D. ''Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew'' | + | * Bultmann, Rudolf. ''Jesus Christ and Mythology''. Pearson, 1981. ISBN 978-0023055706 |

| − | *Geisler, Norman, | + | * Ehrman, Bart D. ''Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew''. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0195182499 |

| − | *Lightner, Robert P. ''Biblical Case for Total Inerrancy'' | + | * Geisler, Norman, and William E. Nix. ''A General Introduction to the Bible''. Moody Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0802429165 |

| + | * Lightner, Robert P. ''A Biblical Case for Total Inerrancy''. Kregel Academic & Professional, 1997. ISBN 978-0825431104 | ||

| + | * Plimer, Ian. ''Telling Lies for God: Reason vs Creationism''. Random House Australia, 1994. ISBN | ||

| + | 978-0091828523 | ||

| + | * Ramm, Bernard. ''The Christian View of Science and Scripture''. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1954. ISBN 978-0802814296 | ||

| + | * Spong, John Shelby. ''Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism: A Bishop Rethinks the Meaning of Scripture.'' HarperOne, 1992. ISBN 978-0060675189 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved October 1, 2023. | |

| − | *[http://www.garyhabermas.com/articles/crj_recentperspectives/crj_recentperspectives.htm Recent Perspectives on the Reliability of the Gospels] by Gary R. Habermas | + | |

| − | *[http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651118_dei-verbum_en.html Dei Verbum] | + | *[http://www.garyhabermas.com/articles/crj_recentperspectives/crj_recentperspectives.htm Recent Perspectives on the Reliability of the Gospels] by Gary R. Habermas. |

| − | + | *[http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651118_dei-verbum_en.html Dei Verbum] Pope Paul VI, November 18, 1965. | |

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

{{Credit|154596932}} | {{Credit|154596932}} | ||

Latest revision as of 03:41, 1 October 2023

Biblical inerrancy is the doctrinal position that in its original form, the Bible is totally without error, and free from all contradiction; referring to the complete accuracy of Scripture, including the historical and scientific parts. Inerrancy is distinguished from biblical infallibility (or limited inerrancy), which holds that the Bible is inerrant on issues of faith and practice but not history or science.

Those adhering to biblical inerrancy usually admit the possibility of errors in translation of sacred text. A famous quote from St. Augustine declares, "It is not allowable to say, 'The author of this book is mistaken;' but either the manuscript is faulty, or the translation is wrong, or you have not understood.”

Inerrancy has come under strong criticism in the modern era. Although several Protestant groups do adhere to it, the Catholic Church no longer strictly upholds the doctrine. Many contemporary Christians, while holding to basic moral and theological truths of the Bible, cannot in good conscience accept its primitive cosmological outlook, or—on close reading—the the troubling ethical attitudes of some its writers.

Inerrancy in context

Many denominations believe that the Bible is inspired by God, who through the human authors is the divine author of the Bible.

This is expressed in the following Bible passage: "All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness 2 Timothy 3:16 NIV).

Although the author here refers to the Hebrew Scripture and not the Christian New Testament, which had not been compiled or completely written at the time of 2 Timothy's writing, most Christians take this saying to apply to the New Testament canon, which came to be accepted in the early fourth century C.E.

Many who believe in the inspiration of scripture teach that it is infallible. However, those who accept the infallibility of scripture hold that its historical or scientific details, which may be irrelevant to matters of faith and Christian practice, may contain errors. Those who believe in inerrancy, however, hold that the scientific, geographic, and historic details of the scriptural texts in their original manuscripts are completely true and without error. On the other hand, a number of contemporary Christians have come to question even the doctrine of infallibility, holding that the biblical writers were indeed inspired at time by God, but that they also express their own, all too human attitudes. In this view, it is ultimately up to the individual conscience to decide what parts of the Bible are truly inspired and accurate, and what parts are the expression of human fallibility. Indeed, much of biblical scholarship in the last two centuries has taken the position that the Bible must be studied in its historical context as a human work, and not only as a sacred scripture which must not be questioned or contradicted by historical or scientific facts.

The theological basis of the belief of inerrancy, in its simplest form, is that as God is perfect, the Bible, as the word of God, must also be perfect, thus, free from error. Proponents of biblical inerrancy also teach that God used the "distinctive personalities and literary styles of the writers" of scripture but that God's inspiration guided them to flawlessly project his message through their own language and personality.

Infallibility and inerrancy refer to the original texts of the Bible. And while conservative scholars acknowledge the potential for human error in transmission and translation, modern translations are considered to "faithfully represent the originals".[1]

In their text on the subject, Geisler and Nix (1986) claim that scriptural inerrancy is established by a number of observations and processes,[2] which include:

- The historical accuracy of the Bible

- The Bible's claims of its own inerrancy

- Church history and tradition

- One's individual experience with God

Major religious views on the Bible

Roman Catholics

Roman Catholic Church teaching on the question of inerrancy has evolved considerably in the last century. Speaking from the claimed authority granted to him by Christ, Pope Pius XII, in his encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu, denounced those who held that the inerrancy was restricted to matters of faith and morals. He reaffirmed the decision of the Council of Trent that the Vulgate Latin edition of the Bible is both sacred and canonical and stated that these "entire books with all their parts" are free "from any error whatsoever." He officially criticized those Catholic writers who wished to restrict the authority of scripture "to matters of faith and morals" as being "in error."

However, Dei Verbum, one of the principal documents of the Second Vatican Council hedges somewhat on this issue. This document states the Catholic belief that all scripture is sacred and reliable because the biblical authors were inspired by God. However, the human dimension of the Bible is also acknowledged as well as the importance of proper interpretation. Careful attention must be paid to the actual meaning intended by the authors, in order to render a correct interpretation. Genre, modes of expression, historical circumstances, poetic liberty, and church tradition are all factors that must be considered by Catholics when examining scripture.

The Roman Catholic Church further holds that the authority to declare correct interpretation rests ultimately with the Church.

Eastern Orthodox Christians

Because the Eastern Orthodox Church emphasizes the authority of councils, which belong to all the bishops, it stresses the canonical uses more than inspiration of scripture. The Eastern Orthodox Church thus believes in unwritten tradition and the written scriptures. Contemporary Eastern Orthodox theologians debate whether these are separate deposits of knowledge or different ways of understanding a single dogmatic reality.

The Eastern Orthodox Church also emphasizes that the scriptures can only be understood according to a normative rule of faith (the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed) and the way of life that has continued from Christ to this day.

Conservative Protestant views

In 1978, a large gathering of American Protestant churches, including representatives of the Conservative, Reformed and Presbyterian, Lutheran, and Baptist denominations, adopted the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy. The Chicago Statement does not imply that any particular traditional translation of the Bible is without error. Instead, it gives primacy to seeking the intention of the author of each original text, and commits itself to receiving the statement as fact depending on whether it can be determined or assumed that the author meant to communicate a statement of fact. Of course, knowing the intent of the original authors is impossible.

Acknowledging that there are many kinds of literature in the Bible besides statements of fact, the Statement nevertheless reasserts the authenticity of the Bible in toto as the word of God. Advocates of the Chicago Statement are worried that accepting one error in the Bible leads one down a slippery slope that ends in rejecting that the Bible has any value greater than some other book"

"The authority of Scripture is inescapably impaired if this total divine inerrancy is in any way limited or disregarded, or made relative to a view of truth contrary to the Bible's own; and such lapses bring serious loss to both the individual and the church."[3]

However, this view is not accepted as normative by many mainline denominations, including many churches and ministers who adopted the Statement.

King James Only

Another belief, King James Only, holds that the translators of the King James Version English Bible were guided by God, and that the KJV is to be taken as the authoritative English Bible. Modern translations differ from the KJV on numerous points, sometimes resulting from access to different early texts, largely as a result of work in the field of Textual Criticism. Upholders of the KJV-Only view nevertheless hold that the Protestant canon of the KJV is itself an inspired text and therefore remains authoritative. The King James Only movement asserts that the KJV is the sole English translation free from error.

Textus Receptus

Similar to the King James Only view is the view that translations must be derived from the Textus Receptus—the name given to the printed Greek texts of the New Testament used by both Martin Luther and the KJV translators—in order to be considered inerrant. For example, in Spanish-speaking cultures the commonly accepted "KJV-equivalent" is the Reina-Valera 1909 revision (with different groups accepting it in addition to the 1909, or in its place the revisions of 1862 or 1960).

Wesleyan and Methodist view of scripture

The Wesleyan and Methodist Christian tradition affirms that the Bible is authoritative on matters concerning faith and practice but does not use the word "inerrant" to describe the Bible. What is of central importance for the Wesleyan Christian tradition is the Bible as a tool which God uses to promote salvation. According to this tradition, the Bible does not itself effect salvation; God initiates salvation and proper creaturely responses consummate salvation. One may be in danger of bibliolatry if one claims that the Bible secures salvation.

Lutheran views

The larger Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada do not officially hold to biblical inerrancy.

The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod, the Lutheran Church—Canada, the Evangelical Lutheran Synod, and many other smaller Lutheran bodies do hold to scriptural inerrancy, though for the most part Lutherans do not consider themselves to be "fundamentalists."

Criticisms of biblical inerrancy

Proponents of biblical inerrancy refer to 2 Timothy 3:16—"all scripture is given by inspiration of God"—as evidence that the whole Bible is inerrant. However, critics of this doctrine think that the Bible makes no direct claim to be inerrant or infallible. Indeed, in context, this passage refers only to the Old Testament writings understood to be scripture at the time it was written.

The idea that the Bible contains no mistakes is mainly justified by appeal to proof-texts that refer to its divine inspiration. However, this argument has been criticized as circular reasoning, because these statements only have to be accepted as true if the Bible is already thought to be inerrant. Moreover, no biblical text says that because a text is inspired, it is therefore always correct in its historical or even its moral statements.

Falsifiability

Biblical inerrancy has also been criticized on the grounds that many statements about history or science that are found in Scripture may be demonstrated to be untenable. Inerrancy is argued to be a falsifiable proposition: If the Bible is found to contain any mistakes or contradictions, the proposition has been refuted. Opinion is divided over which parts of the Bible are trustworthy in the light of these considerations. Critical theologians answer that the Bible contains at least two divergent views of the nature of God: A bloody tribal deity and a loving father. The choice of which viewpoint to value can be based on that which is found to be intellectually coherent and morally challenging, and this is given priority over other teachings found in books of the Bible.

Mythical cosmology, a stumbling-block

The Bible encapsulates a different world-view from the one shared by most people who live in the world now. In the gospels there are demons and possessed people: There is a heaven where God sits and an underworld, where go the dead. Evidence suggests that the cosmology of the Bible assumed that the Earth was flat and that the sun traveled around the Earth, and that the Earth was created in six days within the last 10,000 years.

Christian fundamentalists who advance the doctrine of inerrancy use the supernatural as a means of explanation for miraculous stories from the Bible. An example is the story of Jonah. Jonah 1:15-17 tells how on making a voyage to Tarshish, a storm threatened the survival of the boat, and to calm the storm the sailors:

… took Jonah and threw him overboard, and the raging sea grew calm. At this the men greatly feared the Lord, and they offered a sacrifice to the Lord and made vows to him. But the Lord prepared a great fish to swallow Jonah, and Jonah was inside the fish three days and three nights.

Bernard Ramm explained the miracle of Jonah's sojourn within the great fish or whale as an act of special creation.[4] Critics of this view sarcastically ask whether it had a primitive form of air-conditioning for the well-being of the prophet and a writing-desk with inkpot and pen so that the prophet could compose the prayer which is recorded in Jonah 2. Inerrancy means believing that this mythological cosmology and such stories are 100 percent truthful.[5]

Even more disturbing to some readers are the moral implications of accepting the biblical claim that God commanded the the slaughter of women and children (Numbers 31:17), and even the genocide of rival ethnic groups (1 Samuel 15:3).

The leading twentieth century biblical scholar and theologian Rudolf Bultmann thought that modern people could not accept such propositions in good conscience, and that this understanding of scripture literally could become a stumbling-block to faith.[6] For Bultmann and his followers, the answer was the demythologization of the Christian message, together with a critical approach to biblical studies.

Notes

- ↑ Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy with Exposition Bible Research. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ↑ Norman Geisler and William E. Nix, A General Introduction to the Bible (Moody Publishers, 1986, ISBN 0802429165).

- ↑ The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ↑ Bernard Ramm, The Christian View of Science and Scripture (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1954, ISBN 978-0802814296).

- ↑ Ian Plimer, Telling Lies for God: Reason vs Creationism (Random House, 1994).

- ↑ Rudolf Bultmann, Jesus Christ and Mythology (Pearson, 1981, ISBN 978-0023055706).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boone, Kathleen C. The Bible Tells Them So: The Discourse of Protestant Fundamentalism. State University of New York Press, 1989. ISBN 0887068952

- Bultmann, Rudolf. Jesus Christ and Mythology. Pearson, 1981. ISBN 978-0023055706

- Ehrman, Bart D. Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0195182499

- Geisler, Norman, and William E. Nix. A General Introduction to the Bible. Moody Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0802429165

- Lightner, Robert P. A Biblical Case for Total Inerrancy. Kregel Academic & Professional, 1997. ISBN 978-0825431104

- Plimer, Ian. Telling Lies for God: Reason vs Creationism. Random House Australia, 1994. ISBN

978-0091828523

- Ramm, Bernard. The Christian View of Science and Scripture. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1954. ISBN 978-0802814296

- Spong, John Shelby. Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism: A Bishop Rethinks the Meaning of Scripture. HarperOne, 1992. ISBN 978-0060675189

External links

All links retrieved October 1, 2023.

- Recent Perspectives on the Reliability of the Gospels by Gary R. Habermas.

- Dei Verbum Pope Paul VI, November 18, 1965.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.