Rudolf Bultmann

Rudolf Karl Bultmann (August 20, 1884 â July 30, 1976) was a German theologian of Lutheran background, who was for three decades a professor of New Testament studies at the University of Marburg. He was one of the founders of form criticism and the primary exponent of demythologization, the process of distinguishing the essence of the Christian message from its ancient mythical trappings. Bultmann attempted to reconcile Christian teaching with the modern philosophy of existentialism, emphasizing that each person experiences judgment not in the afterlife or during some future cataclysmic event, but in each moment, as he or she chooses to reject or accept the call of God in the human heart.

While he insisted that much of New Testament Christianity was mythical rather than historical, Bultmann stopped short of denying the basic Christian message that "Christ is Lord." His commitment to conscience above conformity led him to act as part of the confessing church in Hitler's Germany, which refused to condone National Socialism and the Nazi treatment of the Jews. After the war he lectured widely and was the most influential theologian of the post-war era. He is one of the pioneers of historical Jesus research and did important work in attempting to reconcile faith and reason in a modern context.

Biography

Bultmann was born in Wiefelstede, the son of a Lutheran minister. He studied theology at Tübingen and the University of Berlin receiving his doctorate from the University of Marburg with a dissertation on the Epistles of St Paul. He later became a lecturer on the New Testament at Marburg. After brief lectureships at Breslau and Giessen, he returned to Marburg in 1921 as a full professor. He stayed there until his retirement in 1951.

His History of the Synoptic Tradition (1921) is still highly regarded as an essential tool for Gospel research. Bultmann was perhaps the single most influential exponent of historically-oriented principles called "form criticism," which seeks to identify the original form of a piece of biblical narrative, a saying of Jesus, or a parableâas distinguished from the form which has come down to us by way of tradition.

During WWII, he was a member of the Confessing Church and was critical towards National Socialism. He spoke out against the mistreatment of Jews, against nationalistic excesses, and against the dismissal of non-Aryan Christian ministers.

In 1941, Bultmann applied form criticism to the Gospel of John, in which he distinguished the presence of a lost Signs Gospel on which John, alone of the evangelists, depended. This monograph, highly controversial at the time, remains a milestone in research into the historical Jesus. The same year his lecture New Testament and Mythology: The Problem of Demythologizing the New Testament Message called on interpreters to replace traditional theology with the existentialist philosophy of Bultmann's colleague, Martin Heidegger. Bultmann's aim in this endeavor, as he explained, was to make accessible to a literate modern audience the reality of Jesus' teachings. Some scholars, such as the neo-Orthodox theologian Karl Barth, criticized Bultmann for excessive skepticism regarding the historical reliability of the Gospel narratives. Others said he did not go far enough, because he insisted that the Christian message, though based in large part on myth, was still valid.

Although he was already famous in Europe, the full impact of Bultmann was not felt until the English publication of Kerygma and Mythos (1948). After the war he became Europe's most influential theologian. His pupils held leading positions at leading universities, and his views were debated throughout the world. Among his students were Ernst Käsemann, Günther Bornkamm, Hannah Arendt and Helmut Koester. In 1955, his lectures on History and Eschatology: The Presence of Eternity in Britain were particularly influential, as were his later lectures in the U.S., entitled Jesus Christ and Mythology.

Theology

Bultmann was one of the founders of form criticism. He was also the foremost exponent of the process of demythologization of the Christian message.

Bultmann's History of the Synoptic Tradition is considered a masterpiece of this new approach to New Testament analysis and attracted many students. Form criticism, as applied to the Gospels, aimed to place the authentic sayings and actions of Jesus in their original context, understanding Jesus not as the Second Person of the Trinity, but as a Jewish teacher living under the Roman Empire in Galilee and Judea.

Bultmann was convinced the narratives of the life of Jesus were offering theology in story form, rather than historical events and largely accurate quotations from Jesus. Spiritual messages were taught in the familiar language of ancient myth, which has little meaning today. For example, he said:

Jesus Christ is certainly presented as the Son of God, a pre-existent divine being, and therefore to that extent a mythical figure. But he is also a concrete figure of historyâJesus of Nazareth. His life is more than a mythical event, it is a human life which ended in the tragedy of the crucifixion. (Kerygman and Myth, p. 34)

Nevertheless, Bultmann insisted that the Christian message was not to be rejected by modern audiences, however, but given explanation so it could be understood today. Faith must be a determined vital act of will, not a culling and extolling of "ancient proofs."

Jesus and the Word (1926), expressed serious skepticism regarding the New Testament as a reliable source for Jesus' life story. Throughout the 1930s, he published numerous works and become widely known for his goal of demythologization, the process of separating the historical Jesus from the christological descriptions and legends, which Bultmann believed became attached to Jesus through the writings of Saint Paul, the Gospel writers, and the early Church Fathers. In 1941, he published a famous commentary on the Gospel of John.

Bultmann distinguished between two kinds of history: historie and gerschichteâroughly equivalent to the English words "historical" and "historic." The latter has a mythical quality which transcends mere facts. Thus, the Crucifixion of the Christ was historic, in the sense that it was an event that transcends the "crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth." He was careful, however, to distinguish between the demythologization of the Christian texts and issues of faith. For Bultmann, the essence of faith transcends what can be historically known. One can never "know" as a matter of historical fact that "Christ is Lord." However, in response to God's call through His Word, one can respond to Jesus as Lord with certainty, as a proposition of faith.

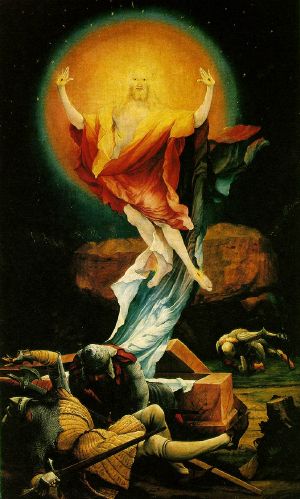

Bultmann took sharp issue with earlier biblical critics such as D. F. Strauss, who, like Bultmann, identified the mythical aspects of Christian faith but also rejected them outright because they were unscientific. For example, Bultmann rejected the historicity of the Resurrection, but not its spiritual significance. "An historical fact which involves a resurrection from the dead is utterly inconceivable," he admitted. For him, the Easter event is not something that happened to the Jesus of history, but something that happened to the disciples, who came to believe that Jesus had been resurrected. Moreover, the resurrected Jesus is indeed a living presence in the lives of Christians. Bultmann's approach was thus not to reject the mythical, but to reinterpret it in modern terms. To deal with this problem, Bultmann used the existentialist method of Heidegger, especially the categories of authentic vs. inauthentic life. In his view the "final judgment" it is not an event in history, but an event which takes place within the heart of each person as he or she responds to the call of God in each existential moment. Humans experience either Heaven or Hell in each moment, and faith means radical obedience to God in the present.

For Bultmann, to be "saved" is not a matter of sacraments and creedal formulas so much as it is to base our existence on God, rather than merely getting by in the world. True Christian freedom means following one's inner conscience, rather than conforming to oppressive or corrupt social order.

Legacy

| â | In every moment slumbers the possibility of being the eschatological moment. You must reawaken it. | â |

One of the leading biblical critics of the twentieth century, Rudolf Bultmann's historical approach to the New Testament provided important new insights, enabling many to view the Bible through skeptical modern eyes while upholding faith in the most basic Christian message. Virtually all New Testament scholars now use the form-critical tools that Bultmann pioneered, even those who do not go as far as he did in his demythologizing of Jesus. His existentialist approach to Christian theology emphasized living every moment as if it were the Final Judgment. His personal example as a member of the Confessing Church in Germany further served to show that Christian faith is not merely a matter belief, but of following Christ's example of living in daily response to God.

Selected works

- History of the Synoptic Tradition. Harper, 1976. ISBN 0-06-061172-3

- Jesus Christ and Mythology. Prentice Hall, 1997. ISBN 0-02-305570-7

- The New Testament and Mythology and Other Basic Writings. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 1984. ISBN 0-8006-2442-4

- Kerygma and Myth. HarperCollins, 2000 edition. ISBN 0-06-130080-2

- The Gospel of John: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press, 1971. ISBN 0-664-20893-2

- Theology of the New Testament: Complete in One Volume. Prentice Hall, 1970. ISBN 0-02-305580-4

- Myth & Christianity: An Inquiry Into The Possibility Of Religion Without Myth. Prometheus Books, 2005. ISBN 1-59102-291-6

- History and Eschatology: The Presence of Eternity (1954â55 Gifford lectures). Greenwood Publishers, 1975. ISBN 0-8371-8123-2

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ashcraft, Morris. Rudolf Bultmann. Makers of the Modern Theological Mind. Word Books, 1972. ISBN 9780876802526

- Dennison, William D. The Young Bultmann: Context for His Understanding of God, 1884-1925. New York: P. Lang, 2008.

- Fergusson, David. Bultmann. Outstanding Christian Thinkers. Health Policy Advisory Center, 1993. ISBN 9780814650370

- Macquarrie, John. The Scope of Demythologizing; Bultmann and His Critics.. Harper Torchbooks, 1966. ASIN B000SGJPT8

- Malet, André. The Thought of Rudolf Bultmann. Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1969. ISBN 1299341500

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.