Rajneesh, Bhagwan

m |

|||

| (66 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} | + | {{approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}}{{Images OK}} |

{{epname|Rajneesh, Bhagwan}} | {{epname|Rajneesh, Bhagwan}} | ||

| − | [[ | + | {{Infobox Artist |

| − | '''Rajneesh Chandra Mohan Jain''' (रजनीश चन्द्र मोहन जैन) (December 11, 1931 – January 19, 1990), better known during the 1960s as '''Acharya Rajneesh''', then during the 1970s and 1980s as '''Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh''' and later taking the name '''Osho,''' was an Indian spiritual teacher. He lived in [[India]] and in other countries including, for a period, the [[United States]], and inspired the [[Osho movement]], a spiritual and [[philosophy|philosophical]] movement that still has many followers. Osho attracted controversy during his life for his teaching, which included sexual and personal freedom of expression and for amassing a large fortune. The movement in the United States was investigated for a number of felonies, including drug smuggling. Osho was refused entry to 21 countries in 1985 after being deported from the U.S.A. for an immigration offense. Opinion of Osho ranges from charlatan, to [[prophet]] of a new age. Those who admire Osho regard the charges against him, including the immigration issue, as concocted, while his critics see them as wholly justified. | + | | honorific_prefix = |

| − | + | | name = Rajneesh | |

| + | | image = Bhagwan beweging gekwetst door reclame-affiche van het NRC met de tekst profeet , Bestanddeelnr 933-0734-cropped.jpg | ||

| + | | image_size = 225px | ||

| + | | caption = Rajneesh in 1981 | ||

| + | | birthname = Chandra Mohan Jain | ||

| + | | birthdate = {{Birth date|mf=yes|1931|12|11}} | ||

| + | | location = Kuchwada, [[Bhopal State]], [[British Raj|British India]] | ||

| + | | deathdate = {{Death date and age|mf=yes|1990|01|19|1931|12|11}} | ||

| + | | deathplace = [[Pune]], [[Maharashtra]], India | ||

| + | | nationality = | ||

| + | | education = [[University of Sagar]] ([[Master of Arts|MA]]) | ||

| + | | movement = [[Neo-sannyasins]]<ref name=Chryssides> George D. Chryssides, ''Exploring New Religions'' (Continuum, 1999, ISBN 978-0304336517).</ref> | ||

| + | | field = [[Spirituality]], [[mysticism]], [[anti-religion]]<ref name=Chryssides/> | ||

| + | | famous works = | ||

| + | | memorials = Osho International Meditation Resort, Pune | ||

| + | | website = {{URL|osho.com}} | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | '''Rajneesh Chandra Mohan Jain''' (रजनीश चन्द्र मोहन जैन) (December 11, 1931 – January 19, 1990), better known during the 1960s as '''Acharya Rajneesh''', then during the 1970s and 1980s as '''Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh''' and later taking the name '''Osho,''' was an Indian spiritual teacher. He lived in [[India]] and in other countries including, for a period, the [[United States]], and inspired the [[Osho movement]], a spiritual and [[philosophy|philosophical]] movement that still has many followers. Osho attracted controversy during his life for his teaching, which included sexual and personal freedom of expression and for amassing a large fortune. The movement in the United States was investigated for a number of felonies, including [[drug]] [[smuggling]]. Osho was refused entry to 21 countries in 1985 after being deported from the U.S.A. for an immigration offense. Opinion of Osho ranges from charlatan, to [[prophet]] of a new age. Those who admire Osho regard the charges against him, including the immigration issue, as concocted, while his critics see them as wholly justified. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

===Early life=== | ===Early life=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Mirror.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Mirror.jpg|thumb|right|300px|"If you really want to know who I am, you have to be as absolutely empty as I am. Then two mirrors will be facing each other, and only emptiness will be mirrored. Infinite emptiness will be mirrored: Two mirrors facing each other. But if you have some idea, then you will see your own idea in me."<ref name=Come>Osho, ''Come Follow to You: Reflections on Jesus of Nazareth'' (Rebel Publishing House Pvt.Ltd, 2001, ISBN 978-8172611095).</ref>]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Osho said this was a major influence on his growth because his grandmother gave him the utmost freedom and respect, leaving him carefree—without an imposed education or restrictions. | + | Osho was born '''Chandra Mohan Jain''' (चन्द्र मोहन जैन) in Kuchwada, a small village in the [[Narsinghpur District]] of [[Madhya Pradesh]] state in [[India]], as the eldest of eleven children of a cloth merchant. His parents, who were [[Taranpanthi]] [[Jainism|Jains]], sent him to live with his maternal grandparents until he was seven years old. Osho said this was a major influence on his growth because his grandmother gave him the utmost freedom and respect, leaving him carefree—without an imposed education or restrictions. |

| − | At seven years old he went back to his parents. He explained that he received a similar kind of respect from his paternal grandfather who was staying with them. He was able to be very open with his grandfather. His grandfather used to tell him, "I know you are doing the right thing. Everyone may tell you that you are wrong. But nobody knows which situation you are in. Only you can decide in your situation. Do whatsoever you feel is right. I will support you. I love you and respect you as well."<ref>Osho, ''From Darkness to Light | + | At seven years old his grandfather died and he went back to his parents. He explained that he received a similar kind of respect from his paternal grandfather who was staying with them. He was able to be very open with his grandfather. His grandfather used to tell him, "I know you are doing the right thing. Everyone may tell you that you are wrong. But nobody knows which situation you are in. Only you can decide in your situation. Do whatsoever you feel is right. I will support you. I love you and respect you as well."<ref name=FromDarkness>Osho, ''From Darkness to Light'' (Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997, ISBN 9783893380206).</ref> He resisted his parents' pressure to get married.<ref name="LT15"/> |

| − | He was a rebellious, but gifted student | + | He was a rebellious, but gifted student. He started his public speaking at the annual [[Sarva Dharma Sammelan]] held at Jabalpur since 1939, organized by the Taranpanthi [[Jain]] community into which he was born. He participated there from 1951 to 1968. Eventually the Jain community stopped inviting him because of his radical ideas. |

Osho said he became spiritually enlightened on March 21, 1953, when he was 21 years old. He said he had dropped all effort and hope. After an intense seven-day process he went out at night to a garden, where he sat under a tree: | Osho said he became spiritually enlightened on March 21, 1953, when he was 21 years old. He said he had dropped all effort and hope. After an intense seven-day process he went out at night to a garden, where he sat under a tree: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>The moment I entered the garden everything became luminous, it was all over the place—the benediction, the blessedness. I could see the trees for the first time—their green, their life, their very sap running. The whole garden was asleep, the trees were asleep. But I could see the whole garden alive, even the small grass leaves were so beautiful.<br> | |

| − | + | I looked around. One tree was tremendously luminous—the maulshree tree. It attracted me, it pulled me towards itself. I had not chosen it, god himself has chosen it. I went to the tree, I sat under the tree. As I sat there things started settling. The whole universe became a benediction.<ref>[https://realization.org/p/osho/my-awakening.html Osho: My Awakening] ''Realization''. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | He finished his studies at D. N. Jain College and the [[University of Sagar]], receiving a B.A. (1955) and an M.A. (1957, with distinction) in [[philosophy]]. He then taught philosophy, first at [[Raipur]] Sanskrit College, and then, until 1966, as a Professor at [[Jabalpur]] University. At the same time, he traveled throughout [[India]], giving lectures critical of [[socialism]] and [[Gandhi]], under the name '''Acharya Rajneesh''' ([[Acharya]] means "teacher"; Rajneesh was a nickname | + | He finished his studies at D. N. Jain College and the [[University of Sagar]], receiving a B.A. (1955) and an M.A. (1957, with distinction) in [[philosophy]]. He then taught philosophy, first at [[Raipur]] Sanskrit College, and then, until 1966, as a Professor at [[Jabalpur]] University. At the same time, he traveled throughout [[India]], giving lectures critical of [[socialism]] and [[Gandhi]], under the name '''Acharya Rajneesh''' ([[Acharya]] means "teacher"; Rajneesh was a nickname he had been given by his family<ref name=FF1>Frances FitzGerald, “A Reporter at Large – Rajneeshpuram” (part 1), ''The New Yorker,'' Sept. 22, 1986.</ref>). In 1962, he began to lead 3– to 10–day [[meditation]] camps, and the first meditation centers (Jivan Jagruti Kendras) started to emerge around his teaching, then known as the Life Awakening Movement (Jivan Jagruti Andolan).<ref name="ASIMA">Osho, ''Autobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic'' (New York: St. Martin's Press/St. Martin's Griffin, 2001, ISBN 0312280718).</ref> He resigned from his teaching post in 1966. |

| − | In 1968, he scandalized [[Hindu]] leaders by calling for freer acceptance of sex; at the Second World Hindu Conference in 1969, he enraged Hindus by criticizing all organized religion and the very institution of priesthood.<ref name="UOLCHN"> | + | In 1968, he scandalized [[Hindu]] leaders by calling for freer acceptance of sex; at the Second World Hindu Conference in 1969, he enraged Hindus by criticizing all organized religion and the very institution of priesthood.<ref name="UOLCHN">[https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv60199 Rajneesh artifacts and ephemera collection, 1981-2004] ''Archives West''. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> |

In 1969 a group of Osho's friends established a foundation to support his work. They settled in an apartment in [[Mumbai]] where he gave daily discourses and received visitors. The number and frequency of visitors soon became too much for the place, overflowing the apartment and bothering the neighbors. A much larger apartment was found on the ground floor (so the visitors would not need to use the elevator, a matter of conflict with the former neighbors). | In 1969 a group of Osho's friends established a foundation to support his work. They settled in an apartment in [[Mumbai]] where he gave daily discourses and received visitors. The number and frequency of visitors soon became too much for the place, overflowing the apartment and bothering the neighbors. A much larger apartment was found on the ground floor (so the visitors would not need to use the elevator, a matter of conflict with the former neighbors). | ||

| Line 31: | Line 47: | ||

===1971–1980=== | ===1971–1980=== | ||

| − | + | From 1971, he was known as '''Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.''' Shree means Sir or Mister; the [[Sanskrit]] word [[Bhagwan]] means "blessed one."<ref>Arthur Anthony Macdonnel, ''A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary'' (Motilal Banarsidass, 2007).</ref> It is commonly used in India as a respectful form of address for spiritual teachers. | |

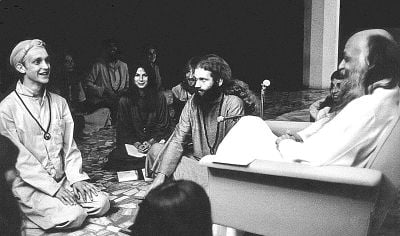

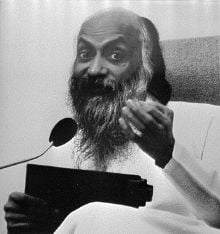

| − | From 1971, he was known as '''Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.''' Shree means Sir or Mister; the [[Sanskrit]] word [[Bhagwan]] means "blessed one."<ref>Arthur Anthony Macdonnel, ''A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary | + | [[File:Rajneesh and disciples at Poona in 1977.jpg|thumb|400px|Rajneesh (right) with his disciples, in 1977]] |

| − | |||

The new apartment also proved insufficient, and the climate of Mumbai was deemed very bad for his delicate health. So, in 1974, on the 21st anniversary of his enlightenment, he and his group moved from the Mumbai apartment to a newly purchased property in Koregaon Park, in the city of [[Pune]], a four-hour trip from [[Mumbai]]. Pune had been the secondary residence of many wealthy families from Mumbai because of the cooler climate (Mumbai lies in a coastal wetland, hot and damp; Pune is inland and much higher, so it is drier and cooler). | The new apartment also proved insufficient, and the climate of Mumbai was deemed very bad for his delicate health. So, in 1974, on the 21st anniversary of his enlightenment, he and his group moved from the Mumbai apartment to a newly purchased property in Koregaon Park, in the city of [[Pune]], a four-hour trip from [[Mumbai]]. Pune had been the secondary residence of many wealthy families from Mumbai because of the cooler climate (Mumbai lies in a coastal wetland, hot and damp; Pune is inland and much higher, so it is drier and cooler). | ||

| − | The two adjoining houses and six acres of land became the nucleus of an [[Ashram]], and those two buildings are still at the heart to the present day. This space allowed for the regular audio and video recording of his discourses and, later, printing for worldwide distribution, which enabled him to reach far larger audiences internationally. The number of Western visitors increased sharply, leading to constant expansion.<ref>Fox, | + | The two adjoining houses and six acres of land became the nucleus of an [[Ashram]], and those two buildings are still at the heart to the present day. This space allowed for the regular audio and video recording of his discourses and, later, printing for worldwide distribution, which enabled him to reach far larger audiences internationally. The number of Western visitors increased sharply, leading to constant expansion.<ref name=Fox>Judith M. Fox, ''Osho Rajneesh (Studies in Contemporary Religion Series)'' Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 2002, ISBN 1560851562).</ref> The Ashram now began to offer a growing number of therapy groups, as well as meditations.<ref>Bob Mullan, ''Life as Laughter: Following Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh'' (New York: Routledge/Routledge and Kegan Paul Books Ltd, 1984, ISBN 0710200439).</ref> |

| − | During one of his discourses in 1980, an attempt on his life was made by a Hindu [[fundamentalist]].<ref> | + | During one of his discourses in 1980, an attempt on his life was made by a Hindu [[fundamentalist]].<ref>[https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pune/first-suicide-squad-was-set-up-in-pune-2-years-ago/articleshow/28605046.cms First Suicide Squad was set up in Pune 2 years ago] ''Times of India,'' November 18, 2002. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> |

Osho taught at the [[Pune]] Ashram from 1974 to 1981. | Osho taught at the [[Pune]] Ashram from 1974 to 1981. | ||

===1981–1990=== | ===1981–1990=== | ||

| + | [[File:Osho Drive By.jpg|thumb|400px|Rajneesh greeted by sannyasins on one of his daily "drive-bys" in Rajneeshpuram, 1982]] | ||

| + | On April 10, 1981, having discoursed daily for nearly 15 years, Osho entered a three-and-a-half-year period of self-imposed public silence,<ref name=Fox/> and [[satsang]]s (silent sitting, with some readings from his works and music) took the place of his discourses. | ||

| − | + | In mid–1981, Osho went to the United States in search of better medical care (he suffered from [[asthma]], [[diabetes]], and severe [[back]] problems). After a brief spell in [[Montclair, New Jersey]],<ref name="NYT160981"> William E. Geist, [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05E2DE1138F935A2575AC0A967948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1 Cult in Castle Troubling Montclair] ''New York Times,'' September 16, 1981. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> his followers bought (for [[United States dollar|US$]] 6 million) a ranch in Wasco County, [[Oregon]], previously known as "The Big Muddy," where they settled for the next four years and legally incorporated a city named [[Rajneeshpuram, Oregon|Rajneeshpuram]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | In mid–1981, Osho went to the United States in search of better medical care (he suffered from [[asthma]], [[diabetes]], and severe [[back]] problems). After a brief spell in [[Montclair, New Jersey]],<ref name="NYT160981"> William E. Geist | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Osho | + | Osho stayed in Rajneeshpuram as the commune's guest, living in a modest home with an indoor swimming pool. Over the coming years, he acquired fame for the large number of [[Rolls-Royce (car)|Rolls-Royce]]s his followers bought for his use, driving a different one every day.<ref>Tim Meyer, The Bhagwan’s Rolls Royces ''Atollon'', May 2020.</ref> |

| − | Increasing conflicts with neighbors and the state of Oregon,<ref name="AM"> Swen Davission | + | Osho ended his period of silence in October 1984. In July 1985, he resumed his daily public discourses in the commune's purpose-built, two-acre meditation hall. According to statements he made to the press, he did so against the wishes of [[Ma Anand Sheela]], his secretary and the commune’s top manager.<ref name=Last>Osho, ''The Last Testament: Interviews With the World Press'' (Rajneesh Foundation Intl, 1986, ISBN 978-0880502504).</ref> |

| + | {{readout||right|250px|Bhagwan Rajneesh, aka Osho, owned over 90 [[Rolls-Royce (car)]]s and drove a different one every day}} | ||

| + | Increasing conflicts with neighbors and the state of Oregon,<ref name="AM"> Swen Davission, [https://ashejournal.com/2015/03/15/ashe-journal-vol-2-issue-2-2003/ The Rise & Fall of Rajneeshpuram] ''Ashé Journal'' March 15, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> as well as serious and criminal misconduct by the commune's management (including conspiracy to murder public officials, wiretapping within the commune, the attempted murder of Osho's personal physician, and a [[bioterrorism]] attack on the citizens of [[The Dalles, Oregon]], using [[salmonella]]), made the position of the Oregon commune untenable.<ref>Frances FitzGerald, [https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1986/09/29/ii-rajneeshpuram II-Rajneeshpuram] ''The New Yorker'' September 29, 1986. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> When the commune's management team who were guilty of these crimes left the U.S. in September 1985, fleeing for Europe, Osho convened a press conference and called on the authorities to undertake an investigation.<ref name="AM"/> This eventually led to the conviction of Sheela and several of her lieutenants. Although Osho himself was not implicated in these crimes, his reputation suffered tremendously, especially in the West.<ref name="LFC233238"/> | ||

| − | In late October 1985, Osho was arrested in [[North Carolina]] as he was allegedly fleeing the U.S. Accused of minor immigration violations, Osho, on the advice of his lawyers, entered an "[[Alford plea]]"—through which a suspect does not admit guilt, but does concede there is enough evidence to convict him—and was given a suspended sentence on condition that he leave the country.<ref name="LFC233238">Carter, | + | In late October 1985, Osho was arrested in [[North Carolina]] as he was allegedly fleeing the U.S. Accused of minor immigration violations, Osho, on the advice of his lawyers, entered an "[[Alford plea]]"—through which a suspect does not admit guilt, but does concede there is enough evidence to convict him—and was given a suspended sentence on condition that he leave the country.<ref name="LFC233238">Lewis F. Carter, ''Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: A Community without Shared Values'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, ISBN 0521385547).</ref> |

Osho then began a world tour, speaking in [[Nepal]], [[Greece]], and [[Uruguay]], among others. Being refused entry visas by more than twenty different countries, he returned to [[India]] in July 1986, and in January 1987, to his old Ashram in [[Pune]], India. He resumed discoursing there. | Osho then began a world tour, speaking in [[Nepal]], [[Greece]], and [[Uruguay]], among others. Being refused entry visas by more than twenty different countries, he returned to [[India]] in July 1986, and in January 1987, to his old Ashram in [[Pune]], India. He resumed discoursing there. | ||

| Line 61: | Line 76: | ||

On January 19, 1990, four years after his arrest, Osho died, at age 58, with [[heart failure]] being the publicly reported cause. Prior to his death, Osho had expressed his belief that his rapid decline in health was caused by some form of poison administered to him by the U.S. authorities during the twelve days he was held without bail in various U.S. prisons. In a public discourse on November 6, 1987, he said that a number of doctors that were consulted had variously suspected [[thallium]], radioactive exposure, and other poisons to account for his failing health: | On January 19, 1990, four years after his arrest, Osho died, at age 58, with [[heart failure]] being the publicly reported cause. Prior to his death, Osho had expressed his belief that his rapid decline in health was caused by some form of poison administered to him by the U.S. authorities during the twelve days he was held without bail in various U.S. prisons. In a public discourse on November 6, 1987, he said that a number of doctors that were consulted had variously suspected [[thallium]], radioactive exposure, and other poisons to account for his failing health: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

| − | + | It does not matter which poison has been given to me, but it is certain that I have been poisoned by Ronald Reagan's American government.<ref>Osho, ''Jesus Crucified Again, This Time in Ronald Reagan's America'' (Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1988, ISBN 978-3893380398).</ref></blockquote> | |

His ashes were placed in his newly built bedroom in one of the main buildings ([[Laozi|LaoTsu]] House) at his last place of residence, his Ashram in [[Pune]], India. The [[epitaph]] reads, "OSHO. Never Born, Never Died. Only Visited this Planet Earth between Dec. 11, 1931 – Jan. 19, 1990." | His ashes were placed in his newly built bedroom in one of the main buildings ([[Laozi|LaoTsu]] House) at his last place of residence, his Ashram in [[Pune]], India. The [[epitaph]] reads, "OSHO. Never Born, Never Died. Only Visited this Planet Earth between Dec. 11, 1931 – Jan. 19, 1990." | ||

== Osho's philosophy == | == Osho's philosophy == | ||

| + | Osho taught that the greatest values in life are (in no specific order) awareness, love, [[meditation]], celebration, creativity, and laughter. He said that [[Enlightenment (concept)|enlightenment]] is everyone's natural state,<ref>Osho, ''The Book of Wisdom: The Heart of Tibetan Buddhism'' (Boston, MA: Element Books, 2000, ISBN 1862047340).</ref> but that one is distracted from realizing it—particularly by the human activity of thought, as well as by emotional ties to societal expectations, and consequent fears and inhibitions. | ||

| − | + | He was a prolific speaker (in both [[Hindi]] and [[English language|English]]) on various spiritual traditions including those of [[Buddha]], [[Krishna]], [[Guru Nanak]], [[Jesus]], [[Socrates]], [[Zen]] masters, [[Gurdjieff]], [[Sufism]], [[Hassidism]], [[Tantra]], and many others. He attempted to ensure that no "system of thought" would define him, since he believed that no philosophy can fully express the truth. | |

| − | + | An experienced orator, he said that words could not convey his message,<ref name=BeStill>Osho, ''Be Still and Know'' (OSHO Media International, 2010, ISBN 978-8172612481).</ref> but that his basic reason for speaking was to give people a taste of [[meditation]].<ref>Osho, ''The Invitation'' (Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997, ISBN 978-3893380350).</ref> He said: | |

| + | <blockquote>I am making you aware of silences without any effort on your part. My speaking is being used for the first time as a strategy to create silence in you. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is not a teaching, a doctrine, a creed. That’s why I can say anything. I am the most free person who has ever existed as far as saying anything is concerned. I can contradict myself in the same evening a hundred times. Because it is not a speech, it has not to be consistent. It is a totally different thing, and it will take time for the world to recognise that a tremendously different experiment was going on. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Just a moment … when I became silent, you become silent. What remains is just a pure awaiting. You are not making any effort; neither am I making any effort. I enjoy talking; it is not an effort. <P> | ||

| + | |||

| + | I love to see you silent. I love to see you laugh, I love to see you dance. But in all these activities, the fundamental remains meditation.<ref>Osho, ''Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram: Truth, Godliness, Beauty'' (Tao Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-8172611927).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | He was often called the "sex guru" after some speeches in the late 1960s on sexuality. These were later compiled under the title ''From Sex to Superconsciousness.''<ref>Osho, ''From Sex to Superconsciousness'' (Rebel Publishing House, 1996, ISBN 978-8172610104).</ref> According to him, "For Tantra everything is holy, nothing is unholy,"<ref>Osho, ''Vigyan Bhairav Tantra'' (Sambodhi Publications, 2019).</ref> and all repressive sexual morality was self-defeating, since one could not transcend sex without experiencing it thoroughly and consciously. In 1985, he told the Bombay ''Illustrated Weekly'': | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>I have never been a celibate. If people believe so, that is their foolishness. I have always loved women—and perhaps more women than anybody else. You can see my beard: it has become grey so quickly because I have lived so intensely that I have compressed almost two hundred years into fifty.<ref name=Last/></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Osho said he loved to disturb people—only by disturbing them could he make them think.<ref>Osho, [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otGQqO2TYMI Absolutely Free to Be Funny: Interview with Jeff McMullen]. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> Accordingly, his discourses were peppered with offensive jokes and outrageous statements lampooning key figures of established religions such as [[Hinduism]], [[Jainism]], or [[Christianity]]. Concerning the [[virgin birth]], for example, he said that [[Jesus]] was a bastard, since he was not [[Saint Joseph|Joseph]]'s biological son.<ref name="LT15">Osho, [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ocbZhRQS9I Marriage and Children] Interview with Howard Sattler, September 12, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | However, he modified his view on unrestricted sex due to the [[AIDS]] epidemic. Followers commented that Osho regarded sex as a matter of personal choice, that is, consenting adults could make their own decisions about [[Human sexuality|sexual relations]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | However, he modified his view on unrestricted sex due to the AIDS epidemic. Followers | ||

===Osho on meditation=== | ===Osho on meditation=== | ||

| − | According to Osho, meditation is not concentration: It is relaxation, let-go.<ref | + | According to Osho, [[meditation]] is not concentration: It is relaxation, let-go.<<ref name=BeStill/> It is a state of watchfulness that has no [[ego]] fulfillment in it, something that happens when one is in a state of not-doing. There is no "how" to this, because "how" means doing—one has to understand that no doing is going to help. In that very understanding, non-doing happens. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Osho said it was very difficult for modern man to just sit and be in meditation, so he devised so-called [[Active Meditation]] techniques to prepare the ground. Some of these preparatory exercises can also be found in western psychological therapies ([[gestalt therapy]]), such as altered breathing, [[gibberish]], laughing, or crying. For each meditation, special music was composed to guide the meditator through the different phases of the meditations. Osho said that [[Dynamic Meditation]] was absolutely necessary for modern man. If people were innocent, he said, there would be no need for Dynamic Meditation, but given that people were repressed, were carrying a large psychological burden, they would first need a catharsis. So Dynamic Meditation was to help them clean themselves out; then they would be able to use any meditation method without difficulty.<ref>Osho, [https://www.osho.com/meditations-contemporary-people Meditations for Contemporary People] ''OSHO International Foundation''. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Apart from his own methods, he also reintroduced minimal parts of several traditional meditation techniques, stripped of what he saw as ritual and tradition, and retaining what he considered to be the most therapeutic parts. He believed that, given sufficient practice, the meditative state can be maintained while performing everyday tasks and that [[Enlightenment (concept)|enlightenment]] is nothing but being continuously in a meditative state. | ||

| + | <blockquote>Nature has come to a point where now, unless you take individual responsibility, you cannot grow. More than this nature cannot do. It has done enough. It has given you life, it has given you opportunity; now how to use it, it has left up to you.</blockquote> | ||

==Controversy and criticism== | ==Controversy and criticism== | ||

| + | Osho had a penchant for courting controversy.<ref name="TOI3104">Neil Pate, [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pune/celluloid-osho-quite-a-hit/articleshow/403145.cms Celluloid Osho, Quite a Hit] ''Times of India'', January 3, 2004. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | + | His liberal views on sex and emotional expression, and the resulting unrestrained behavior of sannyasins in his Pune Ashram at times caused considerable consternation, dismay, and panic among people holding different views on these matters, both in India and the U.S.<ref name="NYT160981"/> A number of Western daily papers routinely focused their reporting on sexual topics. For Osho, sex could be deeply spiritual. | |

| − | + | Osho said that he was "the rich man's guru,"<ref name=FromDarkness/> and that material poverty was not a spiritual value.<ref>Osho, ''Beyond Psychology'' (Tao Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-8172611958). </ref> He was photographed wearing sumptuous clothing and hand-made watches.<ref name="TOI3104"/> He drove a different Rolls-Royce each day—his followers reportedly wanted to buy him 365 of them, one for each day of the year.<ref> Ranjit Lal, [https://web.archive.org/web/20040907145444/http://www.hindu.com/mag/2004/05/16/stories/2004051600330800.htm A hundred years of solitude] ''The Hindu,'' May 16, 2004. Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> Publicity shots of the Rolls-Royces (more than 90 in the end) appeared in the press.<ref name="FF1"/> | |

| − | Osho | + | In his discourses, Osho consistently attacked organizational principles embraced by societies around the world—the family, nationhood, religion.<ref name=Come/> He condemned priests and politicians with equal venom,<ref>Osho, ''Priests and Politicians: The Mafia of the Soul'' (Osho International, 1987, ISBN 3893380000).</ref> and was in turn condemned by them.<ref name="LFC233238"/> |

| − | + | Osho dictated three books while undergoing dental treatment under the influence of [[nitrous oxide]] (laughing gas): ''Glimpses of a Golden Childhood,'' ''Notes of a Madman,'' and ''Books I Have Loved.''<ref>Ma Prem Shunyo, ''My Diamond Days with Osho'' (Full Circle, 2011).</ref> This led to allegations that Osho was addicted to nitrous oxide gas. In 1985, on the American CBS television show ''[[60 Minutes]],'' his former secretary, [[Ma Anand Sheela]], claimed that Osho took sixty milligrams of [[Valium]] every day. | |

| − | + | When questioned by journalists about the allegations of daily Valium and nitrous oxide use, Osho categorically denied both, describing the allegations as "absolute lies."<ref name=Last/> | |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | Osho's books are more popular than ever before, with translations published in 55 different languages. After initial rejection, Osho's teachings have now become a part of mainstream culture in India and [[Nepal]]. Osho is one of only two authors whose entire works have been placed in the Library of [[Parliament of India|India's National Parliament]] in [[New Delhi]] (the other is [[Mahatma Gandhi]]). Excerpts and quotes from Osho's works appear regularly in the ''[[Times of India]]'' and many other Indian newspapers. Prominent admirers include the [[Indian Prime Minister]], Dr. [[Manmohan Singh]], the noted Indian novelist and journalist [[Khushwant Singh]]and the Indian film star and ex-[[Indian Foreign Minister|Minister of State for External Affairs]] [[Vinod Khanna]]. In the West, figures such as the American poet and [[Rumi]] translator [[Coleman Barks]], the American novelist [[Tom Robbins]], and [[Peter Sloterdijk]], German philosopher, author, and TV host, have championed Osho. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Osho's Ashram in [[Pune]] has become the '''Osho International Meditation Resort''', a popular tourist destination that attracts visitors from all over the world.<ref>[https://www.osho.com/osho-meditation-resort OSHO International Meditation Resort] Retrieved September 25, 2022.</ref> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | == | + | == References == |

| − | + | * Carter, Lewis F. ''Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: A Community without Shared Values.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521385547 | |

| − | + | * Chryssides, George D. ''Exploring New Religions''. Continuum, 1999. ISBN 978-0304336517 | |

| − | + | * Fox, Judith M. ''Osho Rajneesh. Studies in Contemporary Religion Series, No. 4.'' Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2002. ISBN 1560851562 | |

| − | * Carter, Lewis F. ''Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: A Community without Shared Values.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN | + | * Macdonnel, Arthur Anthony. ''A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary''. Motilal Banarsidass, 2007. {{ASIN|B003FD4QCW}} |

| − | * | + | * Mullan, Bob. ''Life as Laughter: Following Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.'' New York: Routledge/Routledge and Kegan Paul Books Ltd, 1984. ISBN 0710200439 |

| − | + | * Osho. ''The Last Testament: Interviews With the World Press''. Rajneesh Foundation Intl, 1986. ISBN 978-0880502504 | |

| − | * Fox, Judith M. ''Osho Rajneesh. Studies in Contemporary Religion Series, No. 4.'' Salt Lake City, | + | * Osho. ''Priests and Politicians: The Mafia of the Soul''. Osho International, 1987. ISBN 3893380000 |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''Jesus Crucified Again, This Time in Ronald Reagan's America''. Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1988. ISBN 978-3893380398 |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''From Sex to Superconsciousness''. Rebel Publishing House, 1996. ISBN 978-8172610104 |

| − | + | * Osho. ''From Darkness to Light''. Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 9783893380206 | |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''The Invitation''. Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 978-3893380350 |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''The Book of Wisdom: The Heart of Tibetan Buddhism''. Boston, MA: Element Books, 2000. ISBN 1862047340 |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''Autobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic.'' New York: St. Martin's Press/St. Martin's Griffin, 2001. ISBN 0312280718 |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''Come Follow to You: Reflections on Jesus of Nazareth''. Rebel Publishing House Pvt.Ltd, 2001. ISBN 978-8172611095 |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram: Truth, Godliness, Beauty''. Tao Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-8172611927 |

| − | * Osho. '' | + | * Osho. ''Beyond Psychology''. Tao Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-8172611958) |

| − | * Osho. ''Autobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic.'' New York: St. Martin's Press/St. Martin's Griffin, 2001. ISBN | + | * Osho. ''Be Still and Know''. OSHO Media International, 2010. ISBN 978-8172612481 |

| − | * | + | * Osho. ''Vigyan Bhairav Tantra''. Sambodhi Publications, 2019. |

| − | * Shunyo, Ma Prem. ''My Diamond Days with Osho | + | * Shunyo, Ma Prem. ''My Diamond Days with Osho''. Delhi: Full Circle Publishing Ltd., 2011. {{ASIN|B0054ESU5E}} |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved October 1, 2023. | ||

| − | + | *[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cDgOf2Om28 University of Oregon video on ''The Rise and Fall of Rajneeshpuram'']. | |

| − | *[ | + | *[http://www.religioustolerance.org/rajneesh.htm Résumé of the Osho movement's history]. |

| − | + | *[https://oshoworld.com/ Osho World] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.religioustolerance.org/rajneesh.htm Résumé of the Osho movement's history] | ||

| − | *[ | ||

Latest revision as of 03:34, 1 October 2023

| Rajneesh | |

Rajneesh in 1981 | |

| Birth name | Chandra Mohan Jain |

| Born | December 11 1931 Kuchwada, Bhopal State, British India |

| Died | January 19 1990 (aged 58) Pune, Maharashtra, India |

| Field | Spirituality, mysticism, anti-religion[1] |

| Movement | Neo-sannyasins[1] |

Rajneesh Chandra Mohan Jain (रजनीश चन्द्र मोहन जैन) (December 11, 1931 – January 19, 1990), better known during the 1960s as Acharya Rajneesh, then during the 1970s and 1980s as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and later taking the name Osho, was an Indian spiritual teacher. He lived in India and in other countries including, for a period, the United States, and inspired the Osho movement, a spiritual and philosophical movement that still has many followers. Osho attracted controversy during his life for his teaching, which included sexual and personal freedom of expression and for amassing a large fortune. The movement in the United States was investigated for a number of felonies, including drug smuggling. Osho was refused entry to 21 countries in 1985 after being deported from the U.S.A. for an immigration offense. Opinion of Osho ranges from charlatan, to prophet of a new age. Those who admire Osho regard the charges against him, including the immigration issue, as concocted, while his critics see them as wholly justified.

Biography

Early life

Osho was born Chandra Mohan Jain (चन्द्र मोहन जैन) in Kuchwada, a small village in the Narsinghpur District of Madhya Pradesh state in India, as the eldest of eleven children of a cloth merchant. His parents, who were Taranpanthi Jains, sent him to live with his maternal grandparents until he was seven years old. Osho said this was a major influence on his growth because his grandmother gave him the utmost freedom and respect, leaving him carefree—without an imposed education or restrictions.

At seven years old his grandfather died and he went back to his parents. He explained that he received a similar kind of respect from his paternal grandfather who was staying with them. He was able to be very open with his grandfather. His grandfather used to tell him, "I know you are doing the right thing. Everyone may tell you that you are wrong. But nobody knows which situation you are in. Only you can decide in your situation. Do whatsoever you feel is right. I will support you. I love you and respect you as well."[3] He resisted his parents' pressure to get married.[4]

He was a rebellious, but gifted student. He started his public speaking at the annual Sarva Dharma Sammelan held at Jabalpur since 1939, organized by the Taranpanthi Jain community into which he was born. He participated there from 1951 to 1968. Eventually the Jain community stopped inviting him because of his radical ideas.

Osho said he became spiritually enlightened on March 21, 1953, when he was 21 years old. He said he had dropped all effort and hope. After an intense seven-day process he went out at night to a garden, where he sat under a tree:

The moment I entered the garden everything became luminous, it was all over the place—the benediction, the blessedness. I could see the trees for the first time—their green, their life, their very sap running. The whole garden was asleep, the trees were asleep. But I could see the whole garden alive, even the small grass leaves were so beautiful.

I looked around. One tree was tremendously luminous—the maulshree tree. It attracted me, it pulled me towards itself. I had not chosen it, god himself has chosen it. I went to the tree, I sat under the tree. As I sat there things started settling. The whole universe became a benediction.[5]

He finished his studies at D. N. Jain College and the University of Sagar, receiving a B.A. (1955) and an M.A. (1957, with distinction) in philosophy. He then taught philosophy, first at Raipur Sanskrit College, and then, until 1966, as a Professor at Jabalpur University. At the same time, he traveled throughout India, giving lectures critical of socialism and Gandhi, under the name Acharya Rajneesh (Acharya means "teacher"; Rajneesh was a nickname he had been given by his family[6]). In 1962, he began to lead 3– to 10–day meditation camps, and the first meditation centers (Jivan Jagruti Kendras) started to emerge around his teaching, then known as the Life Awakening Movement (Jivan Jagruti Andolan).[7] He resigned from his teaching post in 1966.

In 1968, he scandalized Hindu leaders by calling for freer acceptance of sex; at the Second World Hindu Conference in 1969, he enraged Hindus by criticizing all organized religion and the very institution of priesthood.[8]

In 1969 a group of Osho's friends established a foundation to support his work. They settled in an apartment in Mumbai where he gave daily discourses and received visitors. The number and frequency of visitors soon became too much for the place, overflowing the apartment and bothering the neighbors. A much larger apartment was found on the ground floor (so the visitors would not need to use the elevator, a matter of conflict with the former neighbors).

On September 26, 1970 he initiated his first disciple or sannyasin at an outdoor meditation camp, one of the large gatherings where he lectured and guided group meditations. His concept of neo-sannyas entailed wearing the traditional orange dress of ascetic Hindu holy men. However, his sannyasins were not expected to follow an ascetic lifestyle.[8]

1971–1980

From 1971, he was known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Shree means Sir or Mister; the Sanskrit word Bhagwan means "blessed one."[9] It is commonly used in India as a respectful form of address for spiritual teachers.

The new apartment also proved insufficient, and the climate of Mumbai was deemed very bad for his delicate health. So, in 1974, on the 21st anniversary of his enlightenment, he and his group moved from the Mumbai apartment to a newly purchased property in Koregaon Park, in the city of Pune, a four-hour trip from Mumbai. Pune had been the secondary residence of many wealthy families from Mumbai because of the cooler climate (Mumbai lies in a coastal wetland, hot and damp; Pune is inland and much higher, so it is drier and cooler).

The two adjoining houses and six acres of land became the nucleus of an Ashram, and those two buildings are still at the heart to the present day. This space allowed for the regular audio and video recording of his discourses and, later, printing for worldwide distribution, which enabled him to reach far larger audiences internationally. The number of Western visitors increased sharply, leading to constant expansion.[10] The Ashram now began to offer a growing number of therapy groups, as well as meditations.[11]

During one of his discourses in 1980, an attempt on his life was made by a Hindu fundamentalist.[12]

Osho taught at the Pune Ashram from 1974 to 1981.

1981–1990

On April 10, 1981, having discoursed daily for nearly 15 years, Osho entered a three-and-a-half-year period of self-imposed public silence,[10] and satsangs (silent sitting, with some readings from his works and music) took the place of his discourses.

In mid–1981, Osho went to the United States in search of better medical care (he suffered from asthma, diabetes, and severe back problems). After a brief spell in Montclair, New Jersey,[13] his followers bought (for US$ 6 million) a ranch in Wasco County, Oregon, previously known as "The Big Muddy," where they settled for the next four years and legally incorporated a city named Rajneeshpuram.

Osho stayed in Rajneeshpuram as the commune's guest, living in a modest home with an indoor swimming pool. Over the coming years, he acquired fame for the large number of Rolls-Royces his followers bought for his use, driving a different one every day.[14]

Osho ended his period of silence in October 1984. In July 1985, he resumed his daily public discourses in the commune's purpose-built, two-acre meditation hall. According to statements he made to the press, he did so against the wishes of Ma Anand Sheela, his secretary and the commune’s top manager.[15]

Increasing conflicts with neighbors and the state of Oregon,[16] as well as serious and criminal misconduct by the commune's management (including conspiracy to murder public officials, wiretapping within the commune, the attempted murder of Osho's personal physician, and a bioterrorism attack on the citizens of The Dalles, Oregon, using salmonella), made the position of the Oregon commune untenable.[17] When the commune's management team who were guilty of these crimes left the U.S. in September 1985, fleeing for Europe, Osho convened a press conference and called on the authorities to undertake an investigation.[16] This eventually led to the conviction of Sheela and several of her lieutenants. Although Osho himself was not implicated in these crimes, his reputation suffered tremendously, especially in the West.[18]

In late October 1985, Osho was arrested in North Carolina as he was allegedly fleeing the U.S. Accused of minor immigration violations, Osho, on the advice of his lawyers, entered an "Alford plea"—through which a suspect does not admit guilt, but does concede there is enough evidence to convict him—and was given a suspended sentence on condition that he leave the country.[18]

Osho then began a world tour, speaking in Nepal, Greece, and Uruguay, among others. Being refused entry visas by more than twenty different countries, he returned to India in July 1986, and in January 1987, to his old Ashram in Pune, India. He resumed discoursing there.

In late December 1988, he said he no longer wished to be referred to as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and shortly afterwards took the name Osho.

On January 19, 1990, four years after his arrest, Osho died, at age 58, with heart failure being the publicly reported cause. Prior to his death, Osho had expressed his belief that his rapid decline in health was caused by some form of poison administered to him by the U.S. authorities during the twelve days he was held without bail in various U.S. prisons. In a public discourse on November 6, 1987, he said that a number of doctors that were consulted had variously suspected thallium, radioactive exposure, and other poisons to account for his failing health:

It does not matter which poison has been given to me, but it is certain that I have been poisoned by Ronald Reagan's American government.[19]

His ashes were placed in his newly built bedroom in one of the main buildings (LaoTsu House) at his last place of residence, his Ashram in Pune, India. The epitaph reads, "OSHO. Never Born, Never Died. Only Visited this Planet Earth between Dec. 11, 1931 – Jan. 19, 1990."

Osho's philosophy

Osho taught that the greatest values in life are (in no specific order) awareness, love, meditation, celebration, creativity, and laughter. He said that enlightenment is everyone's natural state,[20] but that one is distracted from realizing it—particularly by the human activity of thought, as well as by emotional ties to societal expectations, and consequent fears and inhibitions.

He was a prolific speaker (in both Hindi and English) on various spiritual traditions including those of Buddha, Krishna, Guru Nanak, Jesus, Socrates, Zen masters, Gurdjieff, Sufism, Hassidism, Tantra, and many others. He attempted to ensure that no "system of thought" would define him, since he believed that no philosophy can fully express the truth.

An experienced orator, he said that words could not convey his message,[21] but that his basic reason for speaking was to give people a taste of meditation.[22] He said:

I am making you aware of silences without any effort on your part. My speaking is being used for the first time as a strategy to create silence in you.

This is not a teaching, a doctrine, a creed. That’s why I can say anything. I am the most free person who has ever existed as far as saying anything is concerned. I can contradict myself in the same evening a hundred times. Because it is not a speech, it has not to be consistent. It is a totally different thing, and it will take time for the world to recognise that a tremendously different experiment was going on.

Just a moment … when I became silent, you become silent. What remains is just a pure awaiting. You are not making any effort; neither am I making any effort. I enjoy talking; it is not an effort.

I love to see you silent. I love to see you laugh, I love to see you dance. But in all these activities, the fundamental remains meditation.[23]

He was often called the "sex guru" after some speeches in the late 1960s on sexuality. These were later compiled under the title From Sex to Superconsciousness.[24] According to him, "For Tantra everything is holy, nothing is unholy,"[25] and all repressive sexual morality was self-defeating, since one could not transcend sex without experiencing it thoroughly and consciously. In 1985, he told the Bombay Illustrated Weekly:

I have never been a celibate. If people believe so, that is their foolishness. I have always loved women—and perhaps more women than anybody else. You can see my beard: it has become grey so quickly because I have lived so intensely that I have compressed almost two hundred years into fifty.[15]

Osho said he loved to disturb people—only by disturbing them could he make them think.[26] Accordingly, his discourses were peppered with offensive jokes and outrageous statements lampooning key figures of established religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, or Christianity. Concerning the virgin birth, for example, he said that Jesus was a bastard, since he was not Joseph's biological son.[4]

However, he modified his view on unrestricted sex due to the AIDS epidemic. Followers commented that Osho regarded sex as a matter of personal choice, that is, consenting adults could make their own decisions about sexual relations.

Osho on meditation

According to Osho, meditation is not concentration: It is relaxation, let-go.<[21] It is a state of watchfulness that has no ego fulfillment in it, something that happens when one is in a state of not-doing. There is no "how" to this, because "how" means doing—one has to understand that no doing is going to help. In that very understanding, non-doing happens.

Osho said it was very difficult for modern man to just sit and be in meditation, so he devised so-called Active Meditation techniques to prepare the ground. Some of these preparatory exercises can also be found in western psychological therapies (gestalt therapy), such as altered breathing, gibberish, laughing, or crying. For each meditation, special music was composed to guide the meditator through the different phases of the meditations. Osho said that Dynamic Meditation was absolutely necessary for modern man. If people were innocent, he said, there would be no need for Dynamic Meditation, but given that people were repressed, were carrying a large psychological burden, they would first need a catharsis. So Dynamic Meditation was to help them clean themselves out; then they would be able to use any meditation method without difficulty.[27]

Apart from his own methods, he also reintroduced minimal parts of several traditional meditation techniques, stripped of what he saw as ritual and tradition, and retaining what he considered to be the most therapeutic parts. He believed that, given sufficient practice, the meditative state can be maintained while performing everyday tasks and that enlightenment is nothing but being continuously in a meditative state.

Nature has come to a point where now, unless you take individual responsibility, you cannot grow. More than this nature cannot do. It has done enough. It has given you life, it has given you opportunity; now how to use it, it has left up to you.

Controversy and criticism

Osho had a penchant for courting controversy.[28]

His liberal views on sex and emotional expression, and the resulting unrestrained behavior of sannyasins in his Pune Ashram at times caused considerable consternation, dismay, and panic among people holding different views on these matters, both in India and the U.S.[13] A number of Western daily papers routinely focused their reporting on sexual topics. For Osho, sex could be deeply spiritual.

Osho said that he was "the rich man's guru,"[3] and that material poverty was not a spiritual value.[29] He was photographed wearing sumptuous clothing and hand-made watches.[28] He drove a different Rolls-Royce each day—his followers reportedly wanted to buy him 365 of them, one for each day of the year.[30] Publicity shots of the Rolls-Royces (more than 90 in the end) appeared in the press.[6]

In his discourses, Osho consistently attacked organizational principles embraced by societies around the world—the family, nationhood, religion.[2] He condemned priests and politicians with equal venom,[31] and was in turn condemned by them.[18]

Osho dictated three books while undergoing dental treatment under the influence of nitrous oxide (laughing gas): Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, Notes of a Madman, and Books I Have Loved.[32] This led to allegations that Osho was addicted to nitrous oxide gas. In 1985, on the American CBS television show 60 Minutes, his former secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, claimed that Osho took sixty milligrams of Valium every day.

When questioned by journalists about the allegations of daily Valium and nitrous oxide use, Osho categorically denied both, describing the allegations as "absolute lies."[15]

Legacy

Osho's books are more popular than ever before, with translations published in 55 different languages. After initial rejection, Osho's teachings have now become a part of mainstream culture in India and Nepal. Osho is one of only two authors whose entire works have been placed in the Library of India's National Parliament in New Delhi (the other is Mahatma Gandhi). Excerpts and quotes from Osho's works appear regularly in the Times of India and many other Indian newspapers. Prominent admirers include the Indian Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, the noted Indian novelist and journalist Khushwant Singhand the Indian film star and ex-Minister of State for External Affairs Vinod Khanna. In the West, figures such as the American poet and Rumi translator Coleman Barks, the American novelist Tom Robbins, and Peter Sloterdijk, German philosopher, author, and TV host, have championed Osho.

Osho's Ashram in Pune has become the Osho International Meditation Resort, a popular tourist destination that attracts visitors from all over the world.[33]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 George D. Chryssides, Exploring New Religions (Continuum, 1999, ISBN 978-0304336517).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Osho, Come Follow to You: Reflections on Jesus of Nazareth (Rebel Publishing House Pvt.Ltd, 2001, ISBN 978-8172611095).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Osho, From Darkness to Light (Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997, ISBN 9783893380206).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Osho, Marriage and Children Interview with Howard Sattler, September 12, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Osho: My Awakening Realization. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Frances FitzGerald, “A Reporter at Large – Rajneeshpuram” (part 1), The New Yorker, Sept. 22, 1986.

- ↑ Osho, Autobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic (New York: St. Martin's Press/St. Martin's Griffin, 2001, ISBN 0312280718).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rajneesh artifacts and ephemera collection, 1981-2004 Archives West. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Arthur Anthony Macdonnel, A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (Motilal Banarsidass, 2007).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Judith M. Fox, Osho Rajneesh (Studies in Contemporary Religion Series) Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 2002, ISBN 1560851562).

- ↑ Bob Mullan, Life as Laughter: Following Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (New York: Routledge/Routledge and Kegan Paul Books Ltd, 1984, ISBN 0710200439).

- ↑ First Suicide Squad was set up in Pune 2 years ago Times of India, November 18, 2002. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 William E. Geist, Cult in Castle Troubling Montclair New York Times, September 16, 1981. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Tim Meyer, The Bhagwan’s Rolls Royces Atollon, May 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Osho, The Last Testament: Interviews With the World Press (Rajneesh Foundation Intl, 1986, ISBN 978-0880502504).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Swen Davission, The Rise & Fall of Rajneeshpuram Ashé Journal March 15, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Frances FitzGerald, II-Rajneeshpuram The New Yorker September 29, 1986. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Lewis F. Carter, Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: A Community without Shared Values (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, ISBN 0521385547).

- ↑ Osho, Jesus Crucified Again, This Time in Ronald Reagan's America (Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1988, ISBN 978-3893380398).

- ↑ Osho, The Book of Wisdom: The Heart of Tibetan Buddhism (Boston, MA: Element Books, 2000, ISBN 1862047340).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Osho, Be Still and Know (OSHO Media International, 2010, ISBN 978-8172612481).

- ↑ Osho, The Invitation (Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997, ISBN 978-3893380350).

- ↑ Osho, Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram: Truth, Godliness, Beauty (Tao Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-8172611927).

- ↑ Osho, From Sex to Superconsciousness (Rebel Publishing House, 1996, ISBN 978-8172610104).

- ↑ Osho, Vigyan Bhairav Tantra (Sambodhi Publications, 2019).

- ↑ Osho, Absolutely Free to Be Funny: Interview with Jeff McMullen. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Osho, Meditations for Contemporary People OSHO International Foundation. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Neil Pate, Celluloid Osho, Quite a Hit Times of India, January 3, 2004. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Osho, Beyond Psychology (Tao Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-8172611958).

- ↑ Ranjit Lal, A hundred years of solitude The Hindu, May 16, 2004. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Osho, Priests and Politicians: The Mafia of the Soul (Osho International, 1987, ISBN 3893380000).

- ↑ Ma Prem Shunyo, My Diamond Days with Osho (Full Circle, 2011).

- ↑ OSHO International Meditation Resort Retrieved September 25, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carter, Lewis F. Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: A Community without Shared Values. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521385547

- Chryssides, George D. Exploring New Religions. Continuum, 1999. ISBN 978-0304336517

- Fox, Judith M. Osho Rajneesh. Studies in Contemporary Religion Series, No. 4. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2002. ISBN 1560851562

- Macdonnel, Arthur Anthony. A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass, 2007. ASIN B003FD4QCW

- Mullan, Bob. Life as Laughter: Following Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. New York: Routledge/Routledge and Kegan Paul Books Ltd, 1984. ISBN 0710200439

- Osho. The Last Testament: Interviews With the World Press. Rajneesh Foundation Intl, 1986. ISBN 978-0880502504

- Osho. Priests and Politicians: The Mafia of the Soul. Osho International, 1987. ISBN 3893380000

- Osho. Jesus Crucified Again, This Time in Ronald Reagan's America. Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1988. ISBN 978-3893380398

- Osho. From Sex to Superconsciousness. Rebel Publishing House, 1996. ISBN 978-8172610104

- Osho. From Darkness to Light. Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 9783893380206

- Osho. The Invitation. Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 978-3893380350

- Osho. The Book of Wisdom: The Heart of Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, MA: Element Books, 2000. ISBN 1862047340

- Osho. Autobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic. New York: St. Martin's Press/St. Martin's Griffin, 2001. ISBN 0312280718

- Osho. Come Follow to You: Reflections on Jesus of Nazareth. Rebel Publishing House Pvt.Ltd, 2001. ISBN 978-8172611095

- Osho. Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram: Truth, Godliness, Beauty. Tao Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-8172611927

- Osho. Beyond Psychology. Tao Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-8172611958)

- Osho. Be Still and Know. OSHO Media International, 2010. ISBN 978-8172612481

- Osho. Vigyan Bhairav Tantra. Sambodhi Publications, 2019.

- Shunyo, Ma Prem. My Diamond Days with Osho. Delhi: Full Circle Publishing Ltd., 2011. ASIN B0054ESU5E

External links

All links retrieved October 1, 2023.

- University of Oregon video on The Rise and Fall of Rajneeshpuram.

- Résumé of the Osho movement's history.

- Osho World

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.