Difference between revisions of "Beta decay" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Krane, Kenneth S., and David Halliday. 1988. ''Introductory Nuclear Physics.'' New York: Wiley. ISBN 047180553X. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Martin, Brian. 2006. ''Nuclear and Particle Physics: An Introduction''. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0470025328. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Poenaru, D. N. 1996. ''Nuclear Decay Modes.'' Fundamental and Applied Nuclear Physics Series. Philadelphia: Institute of Physics. ISBN 0750303387. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Tipler, Paul, and Ralph Llewellyn. 2002. ''Modern Physics''. 4th ed. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4345-0. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Turner, James E. 1995. ''Atoms, Radiation, and Radiation Protection.'' 2nd ed. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471595810. | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

Revision as of 20:21, 18 October 2007

| Nuclear physics | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Radioactive decay Nuclear fission Nuclear fusion

| ||||||||||||||

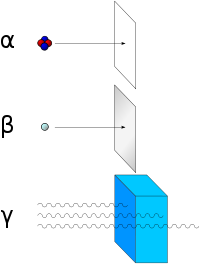

Beta particles are high-energy, high-speed electrons or positrons emitted by certain types of radioactive atomic nuclei such as potassium-40. These particles, designated by the Greek letter beta (β), are a form of ionizing radiation and are also known as beta rays. The release of beta particles by atomic nuclei is a type of radioactive decay and is called beta decay.

There are two forms of beta decay: "beta minus" (β−), involving the release of electrons; and "beta plus" (β+), involving the emission of positrons (which are antiparticles of electrons). In beta minus decay (also simply called "beta decay"), a neutron is converted into a proton, an electron, and an electron-type antineutrino. In beta plus decay (also called "inverse beta decay"), a proton is converted into a neutron, a positron, and an electron-type neutrino.

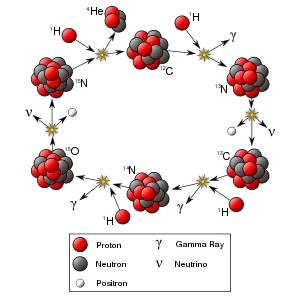

Beta minus decay is common among the neutron-rich fission by-products produced in nuclear reactors, and it accounts for the large numbers of electron antineutrinos produced by these reactors. Free neutrons also decay by this process. Inverse beta decay is one of the steps in nuclear fusion processes that produce energy inside stars. If the neutron or proton is part of an atomic nucleus, the decay process leads to transmutation of one chemical element into another.

History

Historically, the study of beta decay provided the first physical evidence of the neutrino. In 1911, Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn performed an experiment that showed that the energies of electrons emitted by beta decay had a continuous rather than discrete spectrum. This was in apparent contradiction to the law of conservation of energy, as it appeared that energy was lost in the beta decay process. A second problem was that the spin of the Nitrogen-14 atom was 1, in contradiction to the Rutherford prediction of ½.

In 1920-1927, Charles Drummond Ellis (along with James Chadwick and colleagues) established clearly that the beta decay spectrum is really continuous, ending all controversies.

In a famous letter written in 1930, Wolfgang Pauli suggested that in addition to electrons and protons atoms also contained an extremely light neutral particle which he called the neutron. He suggested that this "neutron" was also emitted during beta decay and had simply not yet been observed. In 1931, Enrico Fermi renamed Pauli's "neutron" to neutrino, and in 1934 Fermi published a very successful model of beta decay in which neutrinos were produced.

β− decay (electron emission)

An unstable atomic nucleus with an excess of neutrons may undergo β− decay. In this process, a neutron is converted into a proton, an electron, and an electron-type antineutrino (the antiparticle of the neutrino):

- .

At the fundamental level (depicted in the Feynman diagram below), this process is mediated by the weak interaction. A neutron (one up quark and two down quarks) turns into a proton (two up quarks and one down quark) by the conversion of a down quark to an up quark, with the emission of a W- boson. The W- boson subsequently decays into an electron and an antineutrino.

Beta decay commonly occurs among the neutron-rich fission byproducts produced in nuclear reactors. Free neutrons also decay via this process. This process is the source of the copious amount of electron antineutrinos produced by fission reactors.

β+ decay (positron emission)

Unstable atomic nuclei with an excess of protons may undergo β+ decay, also called inverse beta decay. In this case, energy is used to convert a proton into a neutron, a positron (e+), and an electron-type neutrino ():

- .

On a fundamental level, an up quark is converted into a down quark, emitting a W+ boson that then decays into a positron and a neutrino.

Unlike beta minus decay, beta plus decay cannot occur in isolation, because it requires energy—the mass of the neutron being greater than the mass of the proton. Beta plus decay can only happen inside nuclei when the absolute value of the binding energy of the daughter nucleus is higher than that of the mother nucleus. The difference between these energies goes into the reaction of converting a proton into a neutron, a positron and a neutrino and into the kinetic energy of these particles.

Electron capture

In all cases where β+ decay is allowed energetically (and the proton is a part of a nucleus with electron shells), it is accompanied by the "electron capture" process, in which an atomic electron is captured by a nucleus with the emission of a neutrino:

- .

If, however, the energy difference between initial and final states is low (less than 2mec2), then β+ decay is not energetically possible, and electron capture is the sole decay mode.

Transmutation of elements

If the proton and neutron are part of an atomic nucleus, these decay processes transmute one chemical element into another. For example:

- Beta minus:

- Beta plus:

- Electron capture:

Effects of beta decay

Beta decay does not change the number of nucleons A in the nucleus but changes only its charge Z. Thus the set of all nuclides with the same A can be introduced; these isobaric nuclides may turn into each other via beta decay. Among them, several nuclides (at least one) are beta stable, because they present local minima of the mass excess: if such a nucleus has (A, Z) numbers, the neighbor nuclei (A, Z−1) and (A, Z+1) have higher mass excess and can beta decay into (A, Z), but not vice versa. It should be noted, that a beta-stable nucleus may undergo other kinds of radioactive decay (alpha decay, for example). In nature, most isotopes are beta stable, but a few exceptions exist with half-lives so long that they have not had enough time to decay since the moment of their nucleosynthesis. One example is 40K, which undergoes all three types of beta decay (beta minus, beta plus, and electron capture) with half life of 1.277×109 years.

Some nuclei can undergo double beta decay (ββ decay) where the charge of the nucleus changes by two units. In most practically interesting cases, single beta decay is energetically forbidden for such nuclei, because when β and ββ decays are both allowed, the probability of β decay is (usually) much higher, preventing investigations of very rare ββ decays. Thus, ββ decay is usually studied only for beta stable nuclei. Like single beta decay, double beta decay does not change A; thus, at least one of the nuclides with some given A has to be stable with regard to both single and double beta decay.

Beta decay can be considered as a perturbation as described in quantum mechanics, and thus follows Fermi's Golden Rule.

Inverse beta decay is one of the steps in nuclear fusion processes that produce energy inside stars.

See also

- Alpha particle

- Electron

- Gamma ray

- Neutrino

- Neutron

- Particle physics

- Positron

- Proton

- Radioactive decay

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Krane, Kenneth S., and David Halliday. 1988. Introductory Nuclear Physics. New York: Wiley. ISBN 047180553X.

- Martin, Brian. 2006. Nuclear and Particle Physics: An Introduction. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0470025328.

- Poenaru, D. N. 1996. Nuclear Decay Modes. Fundamental and Applied Nuclear Physics Series. Philadelphia: Institute of Physics. ISBN 0750303387.

- Tipler, Paul, and Ralph Llewellyn. 2002. Modern Physics. 4th ed. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4345-0.

- Turner, James E. 1995. Atoms, Radiation, and Radiation Protection. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471595810.

External links

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.