Religion in Canada

Religion in Canada is characterized by diversity, tolerance and harmony. Canada is a multicultural society with a rich mosaic of religious, cultural, and ethnic communities. Consequently, its demographically heterogeneous population includes many faith groups who live side-by-side in relatively peaceful co-existence.

Although Canada has no official state religion, its constitutional Charter of Rights and Freedoms mentions "God" but no specific beliefs are indicated. While Canadian cities are religiously diverse, its vast countryside tends to be predominantly Christian and most people reported in the national census that they are Christians.[1]

Canada stands out as a model of tolerance, respect, and religious harmony in the modern world today. Support for religious pluralism is an important part of Canada's political culture.

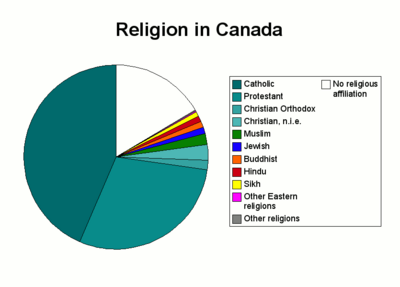

Religious mix

Census results

In the 2001 Canadian national census,[1] 72 percent of the Canadian population list Roman Catholicism or Protestantism as their religion. The Roman Catholic Church in Canada is by far the country's largest single denomination. Those who listed no religion account for 16 percent of total respondents. In the province of British Columbia, however, 35 percent of respondents reported no religionâmore than any single denomination and more than all Protestants combined.[2]

Non-Christian religions in Canada

Non-Christian religions in Canada are overwhelmingly concentrated in metropolitan cites such as Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver, and to a much smaller extent in mid-sized cities such as Ottawa, Quebec, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Halifax. A possible exception is Judaism, which has long been a notable minority even in smaller centers. Much of the increase in non-Christian religions is attributed to changing immigration trends in the last fifty years. Increased immigration from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa has created ever-growing Muslim, Buddhist, Sikh, and Hindu communities. Canada is also home to smaller communities of the BahĂĄ'Ă Faith, Unitarian Universalists, Pagans, and Native American Spirituality.

Islam in Canada

The Muslim population in Canada is almost as old as the nation itself. Four years after Canada's founding in 1867, the 1871 Canadian Census found 13 Muslims among the population. The first Canadian mosque was constructed in Edmonton in 1938, when there were approximately 700 Muslims in the country.[3] This building is now part of the museum at Fort Edmonton Park. The years after World War II saw a small increase in the Muslim population. However, Muslims were still a distinct minority. It was only with the removal of European immigration preferences in the late 1960s that Muslims began to arrive in significant numbers.

According to 2001 census, there were 579,640 Muslims in Canada, just under 2 percent of the population.[4]

Sikhism in Canada

Sikhs have been in Canada since 1897. One of the first Sikh soldiers arrived in Canada in 1897 following Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. British Columbia industrialists were short of labour and thus Sikhs were able to get an early foothold at the turn of the century in British Columbia. Of the nearly 5,000 East Indians in Canada by 1907, over 98 percent were Sikhs, mostly retired British army veterans. However, Sikh immigration to Canada was temporarily banned in 1908, and the population began to shrink.

After the 1960s, Canada's immigration laws were liberalized and racial quotas were removed, allowing far more Sikhs to immigrate to Canada. The Sikh population has rapidly increased in the decades since. Major Sikh communities exist in most of the major cities of British Columbia and Ontario. Sikhs have become an integral part of Canada's economy and culture.

Canadians with no religious affiliation

Non-religious Canadians are most common on the West Coast, particularly in Greater Vancouver.[5] Non-religious Canadians include atheists, agnostics, humanists as well as other nontheists. In 1991, they made up 12.3 percent which increased to 16.2 percent of the population according to the 2001 census. Some non-religious Canadians have formed some associations, such as the Humanist Association of Canada or the Toronto Secular Alliance. In 1991, some non-religious Canadians signed a petition, tabled in Parliament by Svend Robinson, to remove "God" from the preamble to the Canadian Constitution. Shortly afterwards, the same group petitioned to remove "God" from the Canadian national anthem ("O Canada"), but to no avail.

Christianity in Canada

The majority of Canadian Christians attend church infrequently. Cross-national surveys of religiosity rates such as the Pew Global Attitudes Project indicate that, on average, Canadian Christians are less observant than those of the United States but are still more overtly religious than their counterparts in Britain or in western Europe. In 2002, 30 percent of Canadians reported to Pew researchers that religion was "very important" to them. This figure was similar to that in the United Kingdom (33 percent) and Italy (27 percent). In the United States, the equivalent figure was 59 percent, in France, a mere 11 percent. Regional differences within Canada exist, however, with British Columbia and Quebec reporting especially low metrics of traditional religious observance, as well as a significant urban-rural divide. Canadian sociologist of religion, Reginald Bibby, has reported weekly church attendance at about 40 percent since the Second World War, which is higher than those in Northern Europe (for example, Austria 9 percent, Germany 6 percent, France 8 percent, Netherlands 6 percent, and UK 10 percent).

As well as the large churchesâRoman Catholic, United, and Anglican, which together count more than half of the Canadian population as nominal adherentsâCanada also has many smaller Christian groups, including Orthodox Christianity. The Egyptian population in Ontario and Quebec (Greater Toronto in particular) has seen a large influx of the Coptic Orthodox population in just a few decades. The relatively large Ukrainian population of Manitoba and Saskatchewan has produced many followers of the Ukrainian Catholic and Ukrainian Orthodox Churches, while southern Manitoba has been settled largely by Mennonites. The concentration of these smaller groups often varies greatly across the country. Baptists are especially numerous in the Maritimes. The Maritimes and prairie provinces have significant numbers of Lutherans. Southwest Ontario has seen large numbers of German and Russian immigrants, including many Mennonites and Hutterites, as well as a significant contingent of Dutch Reformed. Alberta has seen considerable immigration from the American plains, creating a significant Mormon minority in that province.

Age and religion

According to the 2001 census, the major religions in Canada have the following median age. Canada has a median age of 37.3.[6]

- Presbyterian 46.0

- United Church 44.1

- Anglican 43.8

- Lutheran 43.3

- Jewish 41.5

- Greek Orthodox 40.7

- Baptist 39.3

- Buddhist 38.0

- Roman Catholic 37.8

- Pentecostal 33.5

- Hindu 31.9

- No religion 31.1

- Sikh 29.7

- Muslim 28.1

Government and religion

Canada today has no official church or state religion, and the government is officially committed to religious pluralism. However, significant Christian influence remains in Canadian culture. For example, Christmas and Easter are nationwide holidays, and while Jews, Muslims, and other groups are allowed to take their holy days off work they do not share the same official recognition. The French version of "O Canada," the official national anthem, contains a Christian reference to "carrying the cross." In some parts of the country Sunday shopping is still banned, but this is steadily becoming less common. There was an ongoing battle in the late twentieth century to have religious garb accepted throughout Canadian society, mostly focused on Sikh turbans. Eventually the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Royal Canadian Legion, and other groups accepted members wearing turbans.

While the Canadian government's official ties to Christianity are few, it more overtly recognizes the existence of God.[7] Both the preamble to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the national anthem in both languages refer to God.

Some religious schools are government-funded.

History

Before the arrival of Europeans, the First Nations followed a wide array of mostly animistic religions. The first Europeans to settle in great numbers in Canada were French Catholics, including a large number of Jesuits dedicated to converting the natives; an effort that had only limited success.

The first large Protestant communities were formed in the Maritimes after they were conquered by the British. Unable to convince enough British immigrants to go to the region, the government decided to import continental Protestants from Germany and Switzerland to populate the region and counter balance the Catholic Acadians. This group was known as the Foreign Protestants. This effort proved successful and today the South Shore region of Nova Scotia is still largely Lutheran.

This pattern remained the same after the British conquest of all of New France in 1759. While originally plans to try to convert the Catholic majority were in place, these were abandoned in the face of the American Revolution. The Quebec Act of 1774 acknowledged the rights of the Catholic Church throughout Lower Canada in order to keep the French-Canadians loyal to Britain.

The American Revolution brought about a large influx of Protestants to Canada. United Empire Loyalists, fleeing the rebellious United States, moved in large numbers to Upper Canada and the Maritimes. They comprised a mix of Christian groups with a large number of Anglicans, but also many Presbyterians and Methodists.

In the early nineteenth century in the Maritimes and Upper Canada, the Anglican Church held the same official position it did in Great Britain. This caused tension within English Canada, as much of the populace was not Anglican. Increasing immigration from Scotland created a very large Presbyterian community and they and other groups demanded equal rights. This was an important cause of the 1837 Rebellion in Upper Canada. With the arrival of responsible government, the Anglican monopoly was ended.

In Lower Canada, the Catholic Church was officially preeminent and had a central role in the colony's culture and politics. Unlike English Canada, French-Canadian nationalism became very closely associated with Catholicism. During this period, the Catholic Church in the region became one of the most reactionary in the world. Known as Ultramontane Catholicism, the church adopted positions condemning all manifestations of liberalism, to the extent that even the very conservative popes of the period had to chide it for extremism.

In politics, those aligned with the Catholic clergy in Quebec were known as les bleus ("the blues"). They formed a curious alliance with the staunchly monarchist and pro-British Anglicans of English Canada (often members of the Orange Order) to form the basis of the Canadian Conservative Party. The Liberal Party was largely composed of the anti-clerical French-Canadians, known as les rouges (the reds) and the non-Anglican Protestant groups. In those times, right before elections, parish priests would give sermons to their flock where they said things like Le ciel est bleu et l'enfer est rouge. This translates as "Heaven/the sky is blue and hell is red."

By the late nineteenth century, Protestant pluralism had taken hold in English Canada. While much of the elite were still Anglican, other groups had become very prominent as well. Toronto had become home to the world's single largest Methodist community and it became known as the "Methodist Rome." The schools and universities created at this time reflected this pluralism with major centres of learning being established for each faith. One, King's College, later the University of Toronto, was set up as a non-denominational school.

The late nineteenth century also saw the beginning of a large shift in Canadian immigration patterns. Large numbers of Irish and Southern European immigrants were creating new Catholic communities in English Canada. The population of the west brought significant Eastern Orthodox immigrants from Eastern Europe and Mormon and Pentecostal immigrants from the United States.

Domination of Canadian society by Protestant and Catholic elements continued until well into the twentieth century, however. Up until the 1960s, most parts of Canada still had extensive Lord's Day laws that limited what one could do on a Sunday. The English-Canadian elite were still dominated by Protestants, and Jews and Catholics were often excluded. A slow process of liberalization began after the Second World War in English-Canada. Overtly, Christian laws were expunged, including those against homosexuality. Policies favoring Christian immigration were also abolished.

The most overwhelming change occurred in Quebec. In 1950, the province was one of the most dedicatedly Catholic areas in the world. Church attendance rates were extremely high, books banned by the Papal Index were difficult to find, and the school system was largely controlled by the church. In the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, this was spectacularly transformed. While the majority of Québécois are still professed Catholics, rates of church attendance are today extremely low, in fact, they are the lowest of any region in North America today. Common law relationships, abortion, and support for same-sex marriage are more common in Quebec than in the rest of Canada.

English Canada had seen a similar transition, although less extreme. The United Church of Canada, the country's largest Protestant denomination, is one of the most liberal major Protestant churches in the world. It is committed to gay rights including marriage and ordination, and to the ordination of women. The head of the church even once commented that the resurrection of Jesus might not be a scientific fact. However, that trend appears to have subsided, as the United Church has seen its membership decline substantially since the 1990s, and other mainline churches have seen similar declines.

In addition, a strong current of evangelical Protestantism exists outside of Quebec. The largest groups are found in the Atlantic Provinces and Western Canada, particularly in Alberta, southern Manitoba and the southern interior and Fraser Valley region of British Columbia. There is also a significant evangelical population in southern Ontario. In these areas, particularly outside the Greater Toronto Area, the culture is more conservative, somewhat more in line with that of the midwestern and southern United States, and same-sex marriage, abortion, and common-law relationships are less popular. This movement has grown considerably in the past few years (primarily in those areas listed above) due to strong influences on public policy and stark divides, not unlike those in the United States, although the overall proportion of evangelicals in Canada remains considerably lower and the polarization much less intense. There are very few evangelicals in Quebec and in the largest urban areas, which are generally secular, although there are several congregations above 1000 people in most large cities.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 Statistics Canada, 2001 Census. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- â Statistics Canada, Statistics Canada: British Columbia-One-third Report no Religion Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- â Saudi Aramco World, Canada's Pioneer Mosque. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- â Statistics Canada, Population by religion, by province and territory (2001 Census). Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- â Statistics Canada, British Columbia-One-third Report no Religion. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- â Statistics Canada, Religions in Canada. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- â Government of Canada, Constitution Acts: 1867-1962. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bibby, Reginald. 2004. Restless Gods. Toronto: Novalis, 2004. ISBN 978-2895075554

- Choquette, Robert. 1995. The Oblate Assault on Canada's Northwest. University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 978-0776604022.

- Miedema, Gary R. 2006. For Canada's Sake: Public Religion, Centennial Celebrations, And the Re-making of Canada in the 1960s. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0773528772.

- Murphy, Terrence et al. (eds.). 1996. A Concise History of Christianity in Canada. Toronto: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195407587.

- Stackhouse, John. 1993. Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1573831314.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.