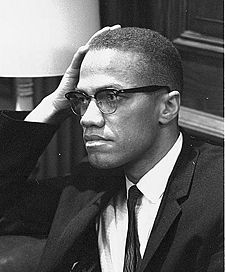

Malcolm X

Malcolm X (May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) (Born Malcolm Little; Arabic name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) was a Muslim minister and a national spokesman for the Nation of Islam. He was also founder of the Muslim Mosque and of the Organization of Afro-American Unity. A self-educated, scholastically-inclined activist who arose from the depths of the black underclass' criminal element, he evolved into a hero-spokesman for those African-Americans who had long held that they and their suffering were invisible to the American mainstream.

As a fiery, socio-political critic of American Christianity's shortcomings and hypocrisies, he made the majority understand that maintaining the pretense of a just American society would be tolerated no longer. His ministry was a courageously scathing critique which held that the conventional systems of Western thought and traditional worldviews were not meeting the "race issue" challenges of the twentieth century, and people should face the fact there was an urgent need to look elsewhere for authentic solutions. In the final year of his short life, after a pilgrimage to Mecca and experience of new enlightenment, Malcolm X came to abandon his virulently anti-white, anti-Christian polemics and emerged more universal in perspective, beholding all men and women as his brothers and sisters under one God.

Introduction

As the United States entered 1920, the raging debate over whether the races should be separated or integrated became more and more sharply focused within the public consciousness. The debate was hottest within the black community. The preceding decade had seen at least 527 (reported) lynchings of American blacks, including the 1918 lynching of the pregnant Mary Turner in Valdosta, Georgia. During the preceding decade, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had been incorporated in New York City, the administration of Democratic President Woodrow Wilson had made it clear that the guarantee of "fair and just treatment for all," meant "whites only." The nation had experienced no fewer than 33 major race riots and the Ku Klux Klan had received a charter from the Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia. Finally, the voice of Booker T. Washington had passed away in 1915 from overwork and fatigue.

America's race crisis had reached a boiling point, and the world was witness to American Christianity's failure to deeply penetrate the culture and make real the tenets of Jesus's teachings on the "fatherhood of God" and the "brotherhood of humanity." Fifty-seven years had passed since the Emancipation Proclamation,[1] and despite the climate of racial hatred, blacks—now 9.9 percent of the total population—were making substantial economic gains. By 1920, there were at least 74,400 blacks in business and/or business-related vocations. African-Americans in America had accumulated more than $1 billion in wealth, and the self-help drive was being led strongly by Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

In the midst of the blazing segregation-versus-integration debate, the black masses struggled daily for the cause of economic independence, coupled with solidarity and group uplift. Into this mix of interior activism and nationalist sentiment was born Malcolm X, whose voice would later ring articulately on behalf of the voiceless, on behalf of those blacks of the side streets, back streets, and ghettos, who were most alienated from the ideals of cultural assimilation and social integration. His message would position itself as the categorical antipode to the doctrine of nonviolent protest and belief in an integrated America that characterized the ministry of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Biography

Birth, early life, and imprisonment

Malcolm Little was born May 19, 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska, to the Reverend Earl and Louise Norton Little. Malcolm's father was an outspoken Baptist lay preacher and a supporter of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Garvey had begun serving his prison sentence for mail fraud just two months prior to Malcolm's birth. Malcolm described his father as a big black man who had lost one eye. Three of Earl Little's brothers had died violently at the hands of white men. One of the three had been lynched. Earl Little fathered three children by a previous marriage before he wedded Malcolm's mother. From this second marriage, he had eight children, of whom Malcolm was the fourth.

Louise Norton Little was born in Grenada and, according to Malcolm, her features were like those of a white woman. Her father was a white man, of whom very little is known except that his mother's conception was not consensual. Malcolm's light complexion and reddish-brown hair were inherited from his mother. For a period of his earlier life, Malcolm thought it a status symbol to be light-skinned. Later on, he professed to have "learned to hate every drop of that white rapist's blood that is in me." As a result of being the lightest child in the family, Malcolm received his father's favoritism. His mother, however, "gave me more hell for the same reason. She was very light herself, but she favored the ones who were darker."[2]

During Malcolm's first four years of life, the family was forced to relocate twice. A white supremacist organization known as the Black Legion issued death threats against the Rev. Earl Little, due to his fervent crusading and active campaigning with the teachings of Marcus Garvey. Even two months prior to Malcolm's birth, while the family was still living in Omaha, they had been harassed by the Ku Klux Klan.[3] By organizing UNIA meetings and preaching Garvey's message in the churches, Rev. Little drew the hostility of these racists. In 1929, the Little's Lansing, Michigan home was torched and burned to the ground. This sacrificial lifestyle of crusading and of incurring wrath caused tension within the household and sparked heated arguments between Malcolm's parents. In 1931, the mutilated body of Rev. Little was found lying across the town's streetcar tracks. Although the police ruled the death an accident,[4] Malcolm and his family were certain that their father had been murdered by members of the Black Legion.[5] Malcolm questioned how his father could have bashed himself in the head, and then lain down across streetcar tracks to get run over and virtually severed in two.[6]

Malcolm's mother made diligent effort to collect on the two insurance policies that her husband had always carried. The smaller one paid off, but the larger one paid nothing because the company claimed Earl Little had committed suicide.[7] This response meant that the desperately needed money would not be forthcoming.

Over the next several years, the family's fortunes continued to dwindle. Destitution, social welfare, hunger, and shame became some of Malcolm's closest acquaintances. The hardships took their toll, and by 1937, Louise Little suffered an emotional breakdown, and was committed to the state mental hospital. The 12-year-old Malcolm and his siblings were subsequently separated and placed in different orphanages and foster homes. Twenty-six years would pass before Little's adult children were able to remove her from that institution.

Malcolm was elected president of his seventh-grade class, and he graduated from junior high school with top honors. Yet, his favorite teacher, upon hearing Malcolm state that he would like to one day become a lawyer, told the young student that the profession of law was "no realistic goal for a nigger."[8] This experience drastically changed Malcolm internally, and he lost interest in further academic achievement.

The pain from his favorite teacher's words had a transformational impact on Malcolm's attitude and view of life. After dropping out of school, he lived and worked for some time in Boston, Massachusetts, and then made his way to Harlem, New York. His schooling in con games, dope peddling, and other petty crimes soon began. By the time he was 18, Malcolm Little was hustling, pimping, and pulling armed robberies. In the underworld, he went by his nickname, "Detroit Red" (for the reddish color of his hair). A cocaine-abusing, atheistic, uncouth heathen, he was at moral rock bottom, and was totally unconcerned about the consequences of a life of crime. Having ethically descended "to the point where I was walking on my own coffin,"[9] Malcolm and his best friend and robbery cohort, Malcolm "Shorty" Jarvis, were arrested and convicted on 14 counts of burglary, in February 1946. Malcolm was not quite 21 years of age.

The Nation of Islam ministry and the prosecution of America

Malcolm was the product of a disintegrated nuclear family and an incarcerated felon. He had spent the preceding seven years on a descent into hell, going from job to job, and from hustle to hustle, reaching out for something that would assuage the childhood pain and make sense of the disappointments and contradictions of life. The next seven years would be spent behind bars, on a path of ascension, self-education, and intellectual renewal, as he found a way to channel the venomous rage that hallmarked his personality.

Malcolm knew the reality of life at the bottom of American society. He conversed in the backstreet vernacular, slang, profanity, and colloquialisms of the black underclass—an underclass desperately crying out for meaning, answers, direction, and leadership. Christianity—black America's overwhelmingly preferred choice of faith—had brought Malcolm none of these. And he despised both the Bible and the "blond, blue-eyed God"[10] it supposedly revealed. In his prison cell, "I would pace for hours, like a caged leopard, viciously cursing aloud to myself. And my favorite targets were the Bible and God…. Eventually, the men in the cell block had a name for me: 'Satan.' Because of my anti-religious attitude."[11] Malcolm critically analyzed himself and society, and he concluded that Christianity is an absurd religion and that God does not exist. To him, the hypocrisy of Christianity was evident in the failure of its white and black adherents to live out its tenets and to solve real societal problems such as racism and poverty.

Through their letters and visits, his siblings encouraged him to improve his penmanship and his command of the English language. This he did, via correspondence courses and exercises. He likewise broadened his vocabulary by a self-directed, privately-motivated journey through the entire dictionary, copying the words and reading them back to himself. Above all, there were the teachings of Elijah Muhammad, to which Malcolm was introduced by his brother, Reginald. Malcolm's sharp and widely-ranging intellectual curiosity was both satisfied and renewed by Muhammad's doctrines. Here at last, for Malcolm, was a worldview that made sense out of nonsense. The young convict was transformed and reborn. His commitment to dispelling his ignorance and obtaining "the true knowledge of the black man"[12] was steel-firm. His voracious appetite for studious, selective, and purposeful reading, he combined with his relish for the weekly debate sessions between inmate teams at the school building of the Norfolk, Massachusetts Prison Colony. Through these sessions, he honed his ability and his confidence to argue the truths of Islam with anyone, anywhere, at anytime.

Upon his parole in August 1952, Malcolm re-entered society with a focus. He knew intimately the degradations of ghetto life, and, even better, the acquiescence of blacks in them. Self-hatred had once dragged him low, and he understood its crippling power. Now he was poised to wage a war of words that would unveil him as a force for the liberation of American blacks. The spiritually disciplined and purposeful lifestyle of a Muslim made his blood boil with expectation and a desire for action. His love for Allah and for Elijah Muhammad knew no bounds. Never again would he be an atheist. Malcolm later reflected on how well he had used his time in prison, to study, to transform himself, and to ready himself for the cause:

I don't think anybody ever got more out of going to prison than I did. In fact, prison enabled me to study far more intensively than I would have if my life had gone differently and I had attended some college. I imagine that one of the biggest troubles with colleges is there are too many distractions, too much panty-raiding, fraternities, and boola-boola and all of that. Where else but in prison could I have attacked my ignorance, by being able to study intensely, sometimes as much as fifteen hours a day?[13]

The world would soon learn that it was not due to a lack of intelligence that Malcolm Little had previously slid into a life of degradation, anger and crime. Over the next 12 years, he crusaded and evangelized to bring blacks out of the darkness and deception of Christianity and into the light and truth of Islam. He committed his blood, sweat, and tears to spread the message of Elijah Muhammad. This man, Malcolm worshiped, and he decided to quit his Ford Motor Company job "to spread his teachings, to establish more temples among the twenty-two million black brothers who were brainwashed and sleeping in the cities of North America."[14]

Having changed his surname from "Little" to "X," and having been ordained a Nation of Islam (NOI) minister, Malcolm launched into what would later appear to have been a nearly meteoric rise in recognition and celebrity. He organized and opened numerous new Muslim Temples (i.e., mosques), and made the NOI such a cultural phenomenon among the black masses that membership increased from four hundred in 1952 to 40,000 in 1964. His incendiary rhetoric and his bold, inflammatory denunciations of perceived injustices generated controversy and headlines. He became an electrifying media magnet. And the Minister Malcolm X was the human quintessence of accusation.

With one vehement aspersion after another, he excoriated the "corrupt, Judeo-Christian" cultural sphere, declaring it "bankrupt and hazardous to black people's health." His trenchant indictment was unleashed with fiery oration. In his worldview, hypocritical, irredeemable, Christian America was a guilty, criminal nation. The NOI was Allah's grand jury, indicting America for lynchings, oppression, racism, and a litany of other offenses. With these indictments, America was to be held without bail, and was to be immediately brought to trial. He, Malcolm X, was Allah's designated prosecutor, by the benevolence and the anointing of Elijah Muhammad. Even millions of black Christians, who would never have even dreamed of joining the NOI, still listened thoughtfully to him, feeling an empathetic tug of the heart:

You see my tears, brothers and sisters…. Tears haven't been in my eyes since I was a young boy. But I cannot help this when I feel the responsibility I have to help you comprehend for the first time what this white man's religion that we call 'Christianity' has done to us…. Brothers and sisters here for the first time, please don't let that shock you. I know you didn't expect this. Because none of us black people have thought that maybe we were making a mistake, not wondering if there wasn't a special religion somewhere for us—a special religion for the black man. Well, there is such a religion. It's called 'Islam.' …. But I'm going to tell you about Islam a little later. First, we need to understand some things about this 'Christianity' before we can understand why the answer for us is Islam."[15]

This was the prosecuting attorney, Malcolm X, pressing charges and making his case. As previously stated, he was the incarnation of indictment against Christian American culture. His Muslim faith indicted the "decadent Judeo-Christian" faith-tradition. And his black nationalism indicted the "deluded integration-ism" advocated by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other "so-called 'Negro-progress' organizations"[16] that constituted the civil rights leadership establishment.

In late 1959, CBS's Mike Wallace Show aired a specially-filmed television documentary entitled The Hate That Hate Produced. This documentary had been created with the full cooperation and consent of the Nation of Islam (NOI). Its goal of shocking the American mainstream with the reality of the NOI's presence was met and exceeded. Almost simultaneously came the release of black scholar Dr. C. Eric Lincoln's book entitled The Black Muslims in America. Together, the documentary and the book propelled Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X onto center stage of the racial segregation-integration controversy.

Over time, the fame and celebrity of Malcolm eventually surpassed that of Muhammad. His eclipse of his mentor was an outcome that Malcolm X never intended or even anticipated. On the contrary, the Minister displayed bold and courageous filial obedience and attendance, as he sought to always promote Elijah Muhammad over himself: "Anyone who has ever listened to me will have to agree that I believed in The Honorable Elijah Muhammad and represented him one hundred per cent. I never tried to take any credit for myself."[17] "Both white people and Negroes—even including Muslims—would make me uncomfortable, always giving me so much credit for the steady progress that the Nation of Islam was making. 'All praise is due to Allah,' I told everybody. 'Anything creditable that I do is due to Mr. Elijah Muhammad.'"[18]

As its recognition and notoriety continued to increase, the NOI enjoyed success at one mass rally after another across America. And both the press and the public mind locked on the Black in "Black Muslims." In vain, Malcolm X tried for two years to clarify that they were "black people in America" who were properly called 'Muslims' because "Our religion is Islam."[19]

Nevertheless, the name stuck, as did the "hate-teaching" image. From 1961-1964, the NOI flourished, as Malcolm X became more well known. The focus was not only on indicting white, Christian America, but the Minister also scolded blacks for their lack of entrepreneurial efforts at self-help. He felt frustrated that the teachings of Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey were being downplayed, and that the focus of the current civil-rights vision was upon litigation and legislatively forcing white people to give blacks a portion of what whites had achieved and built for themselves:

The American black man should be focusing his every effort toward building his own businesses and decent homes for himself. As other ethnic groups have done, let the black people, wherever possible, however possible, patronize their own kind, hire their own kind, and start in those ways to build up the black race's ability to do for itself. That's the only way the American black man is ever going to get respect. One thing the white man can never give the black man is self respect! The black man can never become independent and recognized as a human being who is truly equal with other human beings, until he has what they have, and until he is doing for himself what others are doing for themselves.[20]

With oratory such as this, the minister was leading the charge to rekindle the black nationalism of Marcus Garvey, and thereby to present a challenge to the left-wing, Marxian thrust that was already underfoot in black America, due to the influence of W.E.B. Du Bois and his ideological disciples in the civil rights establishment. In addition, Malcolm's public lectures on the history and the evils of the African slave trade always succeeded in building rapport with his black listeners. By replaying the sins of the past, he was able to give voice to deeply buried grievances. In this way, he could articulate the collective pain and anger and, thereby, use wrath as a structuring leadership principle. At the same time, he told blacks that they could not continuously live in the past, and that they needed to embrace the future-oriented vision of black nationalism, which called for separation between the races, so that blacks could build for themselves the type of economic, cultural, and political system best suited for their long-term survival and progress. Such a vision indicated his faith-tradition's practical, here-and-now focus, as well as its deficit regarding an ethos of forgiveness and love for one's enemies.

Malcolm X's distrust of the civil rights establishment's integrationist drive became even more obvious when he disparagingly labeled the August 28, 1963 March on Washington as the "Farce on Washington." Consistently, the minister derided the middle- and upper-class blacks who constituted the civil rights leadership. Their clamoring for integration with the white majority vexed him to no end. As did Garvey before him, Malcolm concluded that American whites had no genuine desire whatsoever for either integration or its inevitable consequence, intermarriage.

Numerous others of the black nationalist persuasion agreed with Malcolm X, thus clearly demonstrating that Martin Luther King, Jr. did not enjoy universal support among American blacks. The call for integration rang hollow to those who believed that before blacks could learn to collectively love another people or group, they had to nurture sufficient love and respect for themselves and one another. Announced Malcolm: "Beautiful black woman! The Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us that the black man is going around saying he wants 'respect'; well, the black man never will get anybody's respect until he first learns to respect his own women! The black man needs today to stand up and throw off the weaknesses imposed upon him by the slave-master white man! The black man needs to start today to shelter and protect and respect his black woman!"[21]

Embarrassed and frustrated by Malcolm's constant berating them and by his blistering anti-Christian and anti-white utterances, many of the civil rights luminaries made it their policy to completely shun him. Although they professed Jesus's mandate of reaching out to one's enemies, in the minister's case, the distance apparently seemed too far for them. Their ostracism would deeply wound Malcolm.

Marriage and family

On January 14, 1958, Malcolm X was married to Sister Betty X (née Sanders) in Lansing, Michigan. She had joined Muslim Temple Seven in 1956. From their union were born six daughters, all of whom, along with their mother, carry the surname Shabazz. Their names: Attillah (November 1958); Qubilah (December 25, 1960); Ilyasah (July 1962); Amilah (1964); and twins, Malaak and Malikah, born after Malcolm's death in 1965. Sister Betty, who always extolled the memory of her husband after his death, herself died in 1997 as a result of arson committed by her grandson.

Elijah Muhammad, a rude awakening, and questions

During the early 1960s, Malcolm was increasingly confronted with rumors of Elijah Muhammad's extramarital affairs with his own young secretaries. Malcolm initially brushed these rumors aside. Adultery and fornication are strongly condemned in the teachings of the Nation of Islam, and Malcolm could never imagine that his mentor would violate the strict moral codes to which he demanded his own ministers' firm adherence.

Eventually, Malcolm spoke with the women. From their conversations he ascertained that the rumors were indeed facts. In 1963, Elijah Muhammad himself confirmed to Malcolm that the rumors were true. Muhammad then claimed that his philandering followed a pattern established and predicted by the biblical prophets, and was therefore approved by Allah. With this verbal acknowledgment and acceptance that his mentor was indeed a repeat adulterer, Malcolm experienced a period of painful reverberation, following the seismic shaking of his faith. Shaken to the core by these revelations of Muhammad's ethical betrayal, the minister would later comment: "I believed so strongly in Mr. Muhammad that I would have hurled myself between him and an assassin,"[22] "I can't describe the torments I went through."[23]

Hajj, transformation, and the quest for new knowledge

Along with his discovery that Elijah Muhammad had traitorously turned his bevy of eligible young secretaries into a secret seraglio, Malcolm X also experienced, in 1963, a 90-day period of silence, imposed upon him as well, by Muhammad. Elijah explained that this decree was chastisement for the minister's inappropriate comments in response to a reporter's question regarding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In answer to that question, Malcolm had replied that it was a case of "chickens coming home to roost"—that the violence which Kennedy had failed to stop (and at times refused to rein in) had come around to claim his life. Most explosively, Malcolm then added that, because of his country-boy origins, "Chickens coming home to roost never made me sad. It only made me glad."

This remark incited a widespread public outcry and led to the speaking ban. Malcolm, however, even though he complied with the censure, concluded that Muhammad had other reasons for the imposition. The minister suspected that jealousy and the fear of being further upstaged were Muhammad's real ground and motivation. The two men became more and more distant, as Malcolm's faith in Elijah's moral authority continued to erode. On March 12, 1964, Malcolm X officially terminated his relationship with the Nation of Islam, and he founded the Muslim Mosque, Inc. Later that same year, he took the Hajj (pilgrimage) in the Muslim holy land at Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

The experience proved to be life-transforming. The minister met "blond-haired, blue-eyed men I could call my brothers," and he returned to the U.S. on May 12, 1964, with an altered view of the racial segregation-integration debate, as well as with a new name: El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. Prior to the Hajj, Malcolm had already converted to orthodox Islam. Now, as a traditional Sunni Muslim minister, he was even more fully persuaded that the Islamic faith-tradition alone had the potential to erase humanity's racial problems.

During the speech upon his return to the U.S. from Mecca, the minister's openness to intellectual growth and new enlightenment was obvious. He stated:

Human rights are something you were born with. Human rights are your God-given rights. Human rights are the rights that are recognized by all nations of this Earth.

In the past, yes, I have made sweeping indictments of all white people. I will never be guilty of that again, as I know now that some white people are truly sincere, that some truly are capable of being brotherly toward a black man. The true Islam has shown me that a blanket indictment of all white people is as wrong as when whites make blanket indictments against blacks.

Since I learned the truth in Mecca, my dearest friends have come to include all kinds—some Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Hindus, agnostics, and even atheists! I have friends who are called capitalists, socialists, and communists! Some of my friends are moderates, conservatives, extremists—some are even Uncle Toms! My friends today are black, brown, red, yellow, and white!"[24]

While in Mecca, for the first time in my life, I could call a man with blond hair and blue eyes my brother.

In New York, on June 28, 1964, along with A. Peter Bailey and others, Malcolm X founded the U.S. branch of the Organization of Afro-American Unity. His new vision entailed "a socioeconomic program of self-defense and self-assertion, in concert with the emerging nation of Africa. He also projected a vision of black control of black communities."[25] At this point, Malcolm was on the crest of a wave of resurgent black nationalism. Simultaneously, he was diligently seeking an intellectual framework—a paradigm by which he could determine where he was going and what he wanted to be. Now, far beyond the teachings of Elijah Muhammad, he was in search of an adequate ideological home.

Final days, regrets, and assassination

During the course of his intellectual growth and seeking, he made journeys to Africa and to the United Kingdom. He had been certified in Cairo, Egypt as a Sunni Muslim Imam, and had placed himself beneath the spiritual tutelage of an African imam, whom Malcolm had brought back with him to America. He yearned for his own platform of recognition, not eclipsed by Martin Luther King, Jr. During Malcolm's last days, however, he was ostracized from the mainstream, establishment, black leadership and black middle class. He was thus unable, at that time, to realize his longing for leadership legitimacy in the American mainstream sense.

Malcolm never changed his views that black people in the U.S. were justified in defending themselves from their white aggressors. Increasingly, though, he did come to regret his involvement within the Nation of Islam and its tendency to promote racism as a blacks-versus-whites issue. In an interview with Gordon Parks in 1965, he revealed:

"I realized racism isn't just a black and white problem. It's brought bloodbaths to about every nation on earth at one time or another."

He stopped and remained silent for a few moments. He said finally to Parks:

Brother, remember the time that white college girl came into the restaurant—the one who wanted to help the Muslims and the whites get together—and I told her there wasn't a ghost of a chance and she went away crying? Well, I've lived to regret that incident. In many parts of the African continent, I saw white students helping black people. Something like this kills a lot of argument. I did many things as a Black Muslim that I'm sorry for now. I was a zombie then. Like all Black Muslims, I was hypnotized, pointed in a certain direction, and told to march. Well, I guess a man's entitled to make a fool of himself, if he's ready to pay the cost. It cost me twelve years. That was a bad scene, brother. The sickness and madness of those days—I'm glad to be free of them.[26]

Meanwhile, relations with the Nation of Islam had become volatile, following his renunciation of Elijah Muhammad. There were warnings that Malcolm had been marked for assassination. Repeated attempts were made on his life.

On March 20, 1964, LIFE magazine published a famous photograph of Malcolm X holding an M1 Carbine, and pulling back the curtains to peer through a window. The photo was taken in connection with the minister's declaration that he would defend himself from the daily death threats that he and his family were receiving. Undercover FBI informants warned officials that Malcolm X had been marked for assassination. One officer, while undercover with the NOI, is said to have reported that he had been ordered to help plant a bomb in Malcolm's car.

Tensions continued to rise. It was alleged that orders were given by leaders of the NOI to kill Malcolm. In The Autobiography of Malcolm X, he states that as early as 1963, a member of Temple Seven confessed to him that he had received orders from the NOI to murder Malcolm. The NOI won a suit to reclaim Malcolm's Queens, New York house, which NOI officials contended they had paid for. The minister appealed, angry at the thought that his family might soon have no place to live. Then, on the night of February 14, 1965, the East Elmhurst, New York residence of Malcolm, Betty, and their four daughters was firebombed. All family members escaped injury, and no one was charged with the crime.

Seven days later, during a speaking engagement at Manhattan's Audubon Ballroom, Malcolm X, while onstage delivering his address, was rushed by three gunmen who shot him 15 times at close range. Transported to New York's Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, the 39-year-old Malcolm was pronounced dead on arrival. The funeral, held on February 27, 1965, at Faith Temple Church of God in Christ, was attended by 1,600 people. Malcolm X is buried at the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.

Later that year, Betty Shabazz gave birth to their twin daughters.

A complete examination of the assassination and investigation is available from The Smoking Gun and contains a collection of primary sources relating to the assassination.[27]

Legacy and Achievements

Malcolm X's speeches and writings became, for the black poor, a legacy of ideas, critiques, arguments, and sayings that would eventually codify as "Black Power Thought."

The minister's life and speeches helped to spark the drive toward a new black consciousness and black pride. They likewise played a major role in the thrust to extirpate the term "Negro" and to popularize the terms "black" and "Afro-American"—identity concepts with which members of the race could feel more affinity and authenticity. Malcolm stands today as a symbol of the culture, politics, militancy, and struggles of urban black America. His tremendous influence upon the social and political thinking of American blacks is legendary.

Around him, a prolific literature exists. According to Malcolm X biographer, Dr. Marabel Manning, there are today thousands of works bearing the title "Malcolm X." This includes more than 350 films and more than 320 web-based educational resources. Dr. Manning directs the Malcolm X Project at Columbia University,[28] "an ongoing effort to reconstruct the life of the Minister." Dr. Manning is also developing a biography of Malcolm, slated for release by Viking/Penguin Publishers in 2009, with the tentative title, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. In Chicago, there exists Malcolm X Community College, and in Durham, North Carolina, Malcolm X Liberation University and the Malcolm X Society.

Quotations from Malcolm X

- "No government can ever force brotherhood. Men are attracted by spirit. Love is engendered by spirit…. The only true world solution today is governments guided by a true religion of the spirit."[29]

- "America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem."[30]

- "I believe that it would be almost impossible to find anywhere in America a black man who has lived further down in the mud of human society than I have; or a black man who has been more ignorant than I have been; or a black man who has suffered more anguish during his life than I have. But it is only after the deepest darkness that the greatest joy can come; it is only after slavery and prison that the sweetest appreciation of freedom can come."[31]

- "The social philosophy of Black Nationalism only means that we have to get together and remove the evils, the vices, alcoholism, drug addiction, and other evils that are destroying the moral fiber of our community. We ourselves have to lift up the level of our community, the standard of our community, to a higher level—make our own society beautiful, so that we will be satisfied in our own social circles, and won't be running around here, trying to knock our way into a social circle where we're not wanted. So I say, in spreading a gospel such as Black Nationalism, it is not designed to make the black man re-evaluate the white man..., but to make the black man re-evaluate himself."[32]

- "What does this mean, 'Turn the hearts of the children to the fathers.'? The so-called 'Negro' are childlike people—you're like children. No matter how old you get, or how bold you get, or how wise you get, or how rich you get, the white man still calls you what? 'Boy!' Why, you are still a child in his eyesight! And you are a child. Any time you have to let another man set up a factory for you, and you can't set up a factory for yourself, you're a child. Any time another man has to open up businesses for you, and you don't know how to open up businesses for yourself and your people, you're a child. Any time another man sets up schools, and you don't know how to set up your own schools, you're a child. Because a child is someone who sits around and waits for his father to do for him what he should be doing for himself; or what he's too young to do for himself; or what he's too dumb to do for himself. So the white man, knowing that here in America, all the Negro has done—I hate to say it, but it's the truth—all you and I have done is build churches, and let the white man build factories. You and I build churches, and let the white man build schools. You and I build churches, and let the white man build up everything for himself. Then, after you build the church, you have to go and beg the white man for a job, and beg the white man for some education. Am I right or wrong? Do you see what I mean? It's too bad, but it's true. And it's history."[33]

- "So our people not only have to be re-educated to the importance of supporting black business, but the black man himself has to be made aware of the importance of going into business. And once you and I go into business, we own and operate at least the businesses in our community. What we will be doing is developing a situation wherein we will actually be able to create employment for the people in the community. And once you create some employment in the community where you live, it will eliminate the necessity of you and me having to act ignorantly and disgracefully, boycotting and picketing some practice some place else, trying to beg him for a job."[34]

Biographies and Speeches

- The Autobiography of Malcolm X, co-authored by Alex Haley between 1964 and 1965, is based on interviews conducted shortly before Malcolm's assassination. It contains an epilogue and was first published in 1965. The book was named by TIME magazine as one of the ten most important nonfiction books of the twentieth century.

- Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements, edited by George Breitman (ISBN 0802132138). These speeches made during the last eight months of Malcolm's life indicate the power of his newly refined ideas.

- Malcolm X: The Man and His Times, edited with an introduction and commentary by John Henrik Clarke. An anthology of writings, speeches and manifestos along with writings about Malcolm X by an international group of African and African American scholars and activists.

- "Malcolm X: The FBI File," commentary by Clayborne Carson with an introduction by Spike Lee and edited by David Gallen. A source of information documenting the FBI's file on Malcolm, beginning with his prison release in August 1952, and culminating with a 1980 request that the FBI investigate Malcolm's assassination.

- The film Malcolm X was released in 1992, and directed by Spike Lee. Based on The Autobiography of Malcolm X, it starred Denzel Washington as Malcolm; with Angela Bassett as Betty Shabazz; and Al Freeman, Jr. as Elijah Muhammad.

Notes

- ↑ Featured Documents: The Emancipation Proclamation, National Archives & Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. (Logan, IA: Perfection Learning Corporation, 1978, ISBN 0812419537), 2-3.

- ↑ Chronology of the Life and Activities of Malcolm X BrotherMalcolm.net.: A Malcolm X Research Site. Twenty-First Century Books. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Walter Bell, “Assassination of Malcolm X, Black Muslim: A Legend Emerges,” CourtTV Crime Library. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Gale Group Biography.com, “Malcolm X 1925-1965,” Muslim American Society. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 11.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 11.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 36 The full quote is:

Malcolm, one of life's first needs is for us to be realistic. Don't misunderstand me, now. We all like you here, you know that. But you've got to be realistic about being a nigger. A lawyer—that's no realistic goal for a nigger. You need to think about something you can be.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 146.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 219.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 153.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 162.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 180.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 211.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 220.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography,

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 246.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 291.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 247.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 275.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 221.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 287.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 296.

- ↑ Malcolm X - An Islamic Perspective, Call to Islaam Webpage. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Lerone Bennett, Jr. Before The Mayflower: A History of Black America, 6th ed. (Chicago, IL: Johnson Publishing Company, 1988, ISBN 0874850290), 413.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 286.

- ↑ The Smoking Gun: The Malcolm X Files. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Malcolm X Project at Columbia University. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Carol Iannone, "Bad Rap for Malcolm X," National Review 44(24) (Dec. 14, 1992): 47 ff.

- ↑ From a letter Malcolm X wrote to his wife and, concurrently, to Muslim Mosque, Inc., toward the end of his pilgrimage to Mecca; cited in Autobiography.

- ↑ Malcolm X and Alex Haley, Autobiography, 379.

- ↑ The Ballot or the Bullet, April 3, 1964; Cleveland, Ohio.

- ↑ Black Man's History, December 1962.

- ↑ The Ballot or the Bullet, April 12, 1964; Detroit, Michigan.

Further Reading

- Asante, Molefi K. Malcolm X as Cultural Hero: and Other Afrocentric Essays. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1993. ISBN 0865434026

- Breitman, George, ed. Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990. ISBN 0802132138

- Breitman, George. The Last Year of Malcolm X: The Evolution of a Revolutionary. New York: Merit Publishers, 1967.

- Breitman, George, Herman Porter and Baxter Smith. The Assassination of Malcolm X. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1976. ISBN 087348472X

- Brisbane, Robert H. Black Activism; Racial Revolution in the United States, 1954-1970. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1974. ISBN 0817006192

- Carson, Claybourne. Malcolm X: The FBI File. New York: Ballantine Books, 1995. ISBN 0345400097

- Carson, Claybourne, et al. The Eyes on the Prize: Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Accounts from the Black Freedom Struggle, 1954-1990. New York: Penguin Books, 1991. ISBN 0140154035

- Clarke, John Henrik, ed. Malcolm X; the Man and His Times. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1990. ISBN 0865432058

- Cleage, Albert B. and George Breitman. Myths About Malcolm X: Two Views. New York: Merit Publishers, 1969.

- Collins, Rodney P. and Peter A. Bailey. The Seventh Child: A Family Memoir of Malcolm X. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Pub. Group, 1998. ISBN 1559724919

- Cone, James H. Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1991 ISBN 0883447215

- Davis, Thulani. Malcolm X: The Great Photographs. New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang; Distributed by Workman Pub., 1993 ISBN 1556703120

- DeCaro, Louis A. On The Side of My People: A Religious Life of Malcolm X. New York: New York University Press, 1996. ISBN 0814718647

- DeCaro, Louis A. Malcolm and the Cross: The Nation of Islam, Malcolm X, and Christianity. New York: New York University Press, 1998. ISBN 0814718604

- Dyson, Michael Eric. Making Malcolm: The Myth and Meaning of Malcolm X. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 019509235X

- Evanzz, Karl. The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press; Emeryville, CA: Distributed by Publishers Group West, 1992. ISBN 1560250666

- Franklin, Robert Michael. Liberating Visions: Human Fulfillment and Social Justice in African-American Thought. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1990. ISBN 0800623924

- Friedly, Michael. Malcolm X: The Assassination. New York: Carroll & Graf/R. Gallen, 1992. ISBN 0881849227

- Gallen, David. Malcolm X: As They Knew Him. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1992. ISBN 0881848514

- Garrow, David. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Harper Perennial Modern Classics (reprint edition), 2004. ISBN 0060566922

- Goldman, Peter Louis. The Death and Life of Malcolm X. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1979. ISBN 0252007743

- Hampton, Henry, Steve Fayer and Sarah Flynn. Voices of Freedom: Oral Histories from the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s. New York: Bantam Books, 1990. ISBN 0553057340

- Harding, Vincent, Robin D. G. Kelley and Earl Lewis. We Changed the World: African Americans, 1945-1970. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195087968

- Hill, Robert A., ed. Marcus Garvey: Life and Lessons: A Centennial Companion to the Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1987. ISBN 0520062140

- Jamal, Hakim A. From The Dead Level: Malcolm X and Me. New York: Random House, 1972 ISBN 0394462343

- Jenkins, Robert L., ed. The Malcolm X Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002. ISBN 0313292647

- Karim, Benjamin, Peterand Skutches and David Gallen. Remembering Malcolm. New York: Carroll & Graf; Emeryville, CA: Distributed by Publishers Group West, 1992. ISBN 0881849014

- Kly, Yussuf Naim, ed. The Black Book: The True Political Philosophy of Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik El Shabazz). Atlanta: Clarity Press, 1986. ISBN 0932863035

- Leader, Edward Roland. Understanding Malcolm X: The Controversial Changes in His Political Philosophy. New York: Vantage Press, 1993. ISBN 0533095204

- Lee, Spike and Ralph Wiley. By Any Means Necessary: The Trials and Tribulations of The Making Of Malcolm X. New York: Hyperion, 1992. ISBN 1562829130

- Lincoln, Charles Eric. The Black Muslims in America. Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans; Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1993. ISBN 0802807038

- Lomax, Louis. When the Word is Given: A Report on Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, and The Black Muslim World. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979 [1963]. ISBN 0313210020

- Maglangbayan, Shawna. Garvey, Lumumba, and Malcolm: Black National-Separatists. Chicago: Third World Press, 1972. ASIN B0006CBRSQ

- Marable, Manning. Manning Marable On Malcolm X: His Message & Meaning. Westfield, NJ: Open Media, 1992. ASIN B0006OW3HI

- Martin, Tony. Race First: The Ideological and Organizational Struggles of Marcus Garvey and The Universal Negro Improvement Association. Dover, MA: Majority Press, 1986. ISBN 0912469234

- Myers, Walter Dean. Malcolm X: By Any Means Necessary: A Biography. New York: Scholastic, 1993. ISBN 0590464841

- Perry, Bruce. Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America. Barrytown, NY: Station Hill; New York: Distributed by Talman Co., 1991. ISBN 0882681036

- Sales, William W. From Civil Rights to Black Liberation: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1994. ISBN 0896084809

- Shabazz, Ilyasah and Kim McLarin. Growing Up X. New York: One World/Ballantine Books, 2003. ISBN 0345444965

- Strickland, William, et al. Malcolm X: Make It Plain. New York: Viking, 1994. ISBN 067084893X

- T'Shaka, Oba. Political Legacy of Malcolm X. Third World Press, 1984 ISBN 0883781107

- Tuttle, William M. Race Riot: Chicago, the Red Summer of 1919. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996. ISBN 0252065867

- Vincent, Theodore. Black Power and the Garvey Movement. Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1574780406

- Wood, Joe (ed.). Malcolm X: In Our Own Image. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 0312066090

- Woodward, Comer Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877-1913. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1971. ISBN 0807100390

External Links

All links retrieved November 5, 2022.

- The Malcolm X Project at Columbia University

- Malcolm X: A Research Site – Twenty-First Century Books

- Malcolm X Reference Archive

- malcolm-x.org – Seeking to present Malcolm X within an Islamic context

- Ancestry of Malcolm X — Compiled by Christopher Challender Child

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.