Independence Day (United States)

- "Fourth of July" redirects here.

- "4th of July" redirects here.

| Independence Day | |

|---|---|

| |

| Displays of fireworks, such as these over the Washington Monument in 1986, take place across the United States on Independence Day. | |

| Also called | The Fourth of July |

| Observed by | United States |

| Type | National |

| Significance | The day in 1776 that the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress |

| Date | July 4 |

| Celebrations | Fireworks, family reunions, concerts, barbecues, picnics, parades, baseball games |

Independence Day (colloquially the Fourth of July or July 4th) is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. The Continental Congress declared that the thirteen American colonies were no longer subject (and subordinate) to the monarch of Britain, King George III, and were now united, free, and independent states. The Congress had voted to declare independence two days earlier, on July 2, but it was not declared until July 4. Thus, Independence Day is celebrated on July 4.

Independence Day is commonly associated with fireworks, parades, barbecues, carnivals, fairs, picnics, concerts, baseball games, family reunions, political speeches, and ceremonies, in addition to various other public and private events celebrating the history, government, and traditions of the United States. As an official holiday, it is a time for family and friends to share the patriotic celebration together.

History

During the American Revolution, the legal separation of the thirteen colonies from Great Britain in 1776 occurred on July 2, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia declaring the United States independent from Great Britain's rule.[1]

After voting for independence, Congress turned its attention to the Declaration of Independence, a statement explaining this decision, which had been prepared by a Committee of Five, with Thomas Jefferson as its principal author. Congress debated and revised the wording of the Declaration, finally approving it two days later on July 4. A day earlier, John Adams had written to his wife Abigail:

The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.[2]

Adams's prediction was off by two days. From the outset, Americans celebrated independence on July 4, the date shown on the much-publicized Declaration of Independence, rather than on July 2, the date the resolution of independence was approved in the closed session of Congress.[3]

Historians have long disputed whether members of Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, even though Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin all later wrote that they had signed it on that day. Most historians have concluded that the Declaration was signed nearly a month after its adoption, on August 2, 1776, and not on July 4 as is commonly believed.[4][1][5]

By a remarkable coincidence, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, the only two signatories of the Declaration of Independence later to serve as presidents of the United States, both died on the same day: July 4, 1826, which was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration.[6] (Only one other signatory, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, survived them, dying in 1832.[7]) Although not a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, James Monroe, another Founding Father who was elected as president, also died on July 4, in 1831. He was the third President who died on the anniversary of independence. Calvin Coolidge, the 30th president, was born on July 4, 1872.

Customs

Independence Day is a national holiday marked by patriotic displays. Similar to other summer-themed events, Independence Day celebrations often take place outdoors. According to ,[8] Independence Day is a federal holiday, so all non-essential federal institutions (such as the postal service and federal courts) are closed on that day.

Independence Day is commonly associated with fireworks, parades, barbecues, carnivals, fairs, picnics, concerts, baseball games, family reunions, political speeches, and ceremonies, in addition to various other public and private events celebrating the history, government, and traditions of the United States. A salute of one gun for each state in the United States, called a "salute to the union," is fired on Independence Day at noon by any capable military base.[9]

The night before the Fourth was once the focal point of celebrations, marked by raucous gatherings often incorporating bonfires as their centerpiece. In New England, towns competed to build towering pyramids, assembled from barrels and casks. They were lit at nightfall to usher in the celebration. The highest were in Salem, Massachusetts, with pyramids composed of as many as forty tiers of barrels. These made the tallest bonfires ever recorded. The custom flourished in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and is still practiced in some New England towns.[10]

The first week of July is typically one of the busiest United States travel periods of the year, as many people use what is often a three-day holiday weekend for extended vacation trips. Families often celebrate Independence Day by hosting or attending a picnic or barbecue; many take advantage of the day off and, in some years, a long weekend to gather with relatives or friends. Decorations (such as streamers, balloons, and clothing) are generally colored red, white, and blue, the colors of the American flag. Parades are often held in the morning, before family get-togethers, while fireworks displays occur in the evening after dark at such places as parks, fairgrounds, and town squares.

Fireworks shows are held in many states. Also, many fireworks are sold for personal use or as an alternative to a public show. Safety concerns have led some states to ban fireworks or limit the sizes and types allowed.

Independence Day fireworks are often accompanied by patriotic songs such as the national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner"; "God Bless America"; "America the Beautiful"; "My Country, 'Tis of Thee"; "This Land Is Your Land"; "Stars and Stripes Forever"; and, regionally, "Yankee Doodle" in northeastern states and "Dixie" in southern states. Additionally, Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, which celebrates the successful Russian defense against Napoleon's invading army during the War of 1812, is often performed. The overture's brass fanfare finale, complete with ringing chimes and its climactic volley of cannon fire, signals the start of the fireworks display.

New York City has the largest fireworks display in the country sponsored by Macy's, with large quantities of pyrotechnics exploded from barges stationed in either the Hudson River or the East River near the Brooklyn Bridge. The bridge has also served as a launch pad for fireworks on several occasions.[11] Other major displays are in Seattle on Lake Union; in San Diego over Mission Bay; in Boston on the Charles River; in Philadelphia over the Philadelphia Museum of Art; in San Francisco over the San Francisco Bay; and on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.[12]

Historical Observances

- In 1777, thirteen gunshots were fired in salute, once at morning and once again as evening fell, on July 4 in Bristol, Rhode Island. An article in July 18, 1777 issue of The Virginia Gazette noted a celebration in Philadelphia in a manner a modern American would find familiar: an official dinner for the Continental Congress, toasts, 13-gun salutes, speeches, prayers, music, parades, troop reviews, and fireworks. Ships in port were decked with red, white, and blue bunting.[13]

- In 1778, from his headquarters at Ross Hall, near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General George Washington marked July 4 with a double ration of rum for his soldiers and an artillery salute (feu de joie). Across the Atlantic Ocean, ambassadors John Adams and Benjamin Franklin held a dinner for their fellow Americans in Paris, France.[13]

- In 1779, July 4 fell on a Sunday. The holiday was celebrated on Monday, July 5.[13]

- In 1781, the Massachusetts General Court became the first state legislature to recognize July 4 as a state celebration.[13]

- In 1783, Salem, North Carolina, held a celebration with a challenging music program assembled by Johann Friedrich Peter entitled The Psalm of Joy. The town claims to be the first public July 4 event, as it was carefully documented by the Moravian Church, and there are no government records of any earlier celebrations.[14]

- In 1870, the U.S. Congress made Independence Day an unpaid holiday for federal employees.[13]

- In 1938, Congress changed Independence Day to a paid federal holiday.[13]

Notable celebrations

- Held since 1785, the Bristol Fourth of July Parade in Bristol, Rhode Island, is the oldest continuous Independence Day celebration in the United States.[15]

- Since 1868, Seward, Nebraska, has held a celebration on the same town square. In 1979 Seward was designated "America's Official Fourth of July City-Small Town USA" by resolution of Congress. Seward has also been proclaimed "Nebraska's Official Fourth of July City" by Governor James Exon in proclamation. Seward is a town of 6,000 but swells to 40,000+ during the July 4 celebrations.[16]

- Since 1959, the International Freedom Festival is jointly held in Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario, during the last week of June each year as a mutual celebration of Independence Day and Canada Day (July 1). It culminates in a large fireworks display over the Detroit River.

- The famous Macy's fireworks display usually held over the East River in New York City has been televised nationwide on NBC, and locally on WNBC-TV since 1976. In 2009, the fireworks display was returned to the Hudson River for the first time since 2000 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Henry Hudson's exploration of that river.[17]

- The Boston Pops Orchestra has hosted a music and fireworks show over the Charles River Esplanade called the "Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular" annually since 1974.[18] Canons are traditionally fired during the 1812 Overture. The event was broadcast nationally from 1991 until 2002 on A&E, and from 2002 to 2012 by CBS and its Boston station WBZ-TV. The national broadcast was put on hiatus beginning in 2013, although it continues to be broadcast on local stations.

- On the Capitol lawn in Washington, DC, A Capitol Fourth, a free concert broadcast live by PBS, NPR, and the American Forces Network, precedes the fireworks and attracts over half a million people annually.[19]

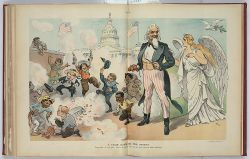

Celebration gallery

Criticism

In 1852, Frederick Douglass gave a speech now called "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" at a time when slavery was still legal in Southern states, and free African-Americans elsewhere still faced discrimination and brutality. Douglass found the celebration of "justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence" offensive to enslaved people who had none of those things. The Declaration of Independence famously asserts that "all men are created equal, but commentator Arielle Gray recommends that those celebrating the holiday consider how the freedom promised by the phrase "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" was not granted to African Americans denied citizenship and equal protection before the passage of the Fourteen Amendment to the United States Constitution.[20]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carl L. Becker, The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas (Andesite Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1298758958).

- ↑ Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776 Massachusetts Historical Society Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ↑ Pauline Maier, Making Sense of the Fourth of July American Heritage 48(4) (July/August 1997). Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ↑ Edmund Cody Burnett, The Continental Congress (W.W. Norton, 1964).

- ↑ For the minority scholarly argument that the Declaration was signed on July 4, see Wilfred J. Ritz, The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 Law and History Review 4(1) (Spring 1986): 179–204.

- ↑ Jon Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power (Random House, 2013, ISBN 978-0812979480).

- ↑ Signers of the Declaration of Independence National Archives. Retrieved June 20. 2020.

- ↑ 5 U.S. Code § 6103. Holidays Legal Information Institute. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ↑ Origin of the 21-Gun Salute U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ↑ Yoni Appelbaum, The Night Before the Fourth The Atlantic, July 1, 2011. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ↑ 2020 Macy's 4th of July Fireworks Cititour. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ↑ Samantha Nelson, 10 of the nation's Best 4th of July Firework Shows USA Today, July 1, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 James R. Heintze, The Fourth of July Encyclopedia (McFarland, 2013, ISBN 978-0786477166).

- ↑ Michael Graff, Time Stands Still in Old Salem Our State, October 31, 2012. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ↑ Bristol Fourth of July Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ↑ Fascinating Facts About the Seward Fourth of July Celebration Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ↑ Macy's July 4th Fireworks Display NYCData. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ↑ History of the Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular Boston Pops. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ↑ A Star-Spangled Birthday Party! A Capitol Fourth. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ↑ Arielle Gray, As A Black American, I Don't Celebrate The Fourth Of July The ARTery, July 3, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Becker, Carl L. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. Andesite Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1298758958

- Burnett, Edmund Cody. The Continental Congress. W.W. Norton, 1964. ASIN B0007DMWQU

- Criblez, Adam. Parading Patriotism: Independence Day Celebrations in the Urban Midwest, 1826–1876. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0875806921

- Heintze, James R. The Fourth of July Encyclopedia. McFarland, 2013. ISBN 978-0786477166

- Meacham, Jon. Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House, 2013. ISBN 978-0812979480

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- Fourth of July – Independence Day History.com

- The Story of the Fourth of July ConstitutionFacts.com

- The History of the Fourth of July Military.com

- The History of America’s Independence Day PBS

- History of Independence Day NPS

- The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro by Frederick Douglass

- Fourth of July 2015 Fireworks in New York City on Youtube

| |||||

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.