Hieronymus Bosch

| Hieronymus Bosch | |

Hieronymus Bosch; alleged self-portrait (around 1516) | |

| Birth name | Jheronimus van Aken |

| Born | c. 1450 |

| Died | August 9, 1516 's-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands |

| Field | Painting, drawing |

| Movement | Renaissance |

| Influenced | Pieter Brueghel the Elder Surrealism Joan Miró |

Hieronymus Bosch (pronounced /ňĆha…™…ôňąr…ín…ôm…ôs b…í É/, Dutch /je'…ĺonimus b…Ēs/, born Jeroen Anthonissen van Aken /j…ô'r än …Ďn'toniňźzoňźn v…Ďn 'aňźk…ôn/ c. 1450 ‚Äď August 9, 1516) was an Early Netherlandish painter of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Many of his works depict sin and human moral failings.

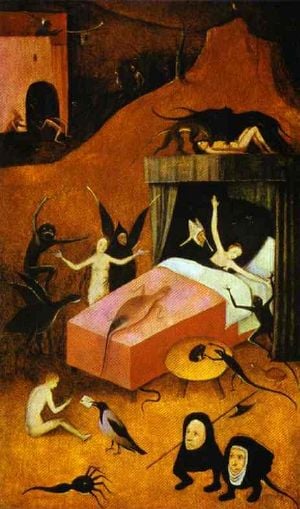

Bosch used images of demons, half-human animals and machines to evoke fear and confusion to portray the evil of man. His works contain complex, highly original, imaginative, and dense use of symbolic figures and iconography, some of which was obscure even in his own time.

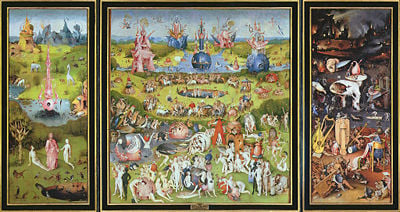

His masterpiece, The Garden of Earthly Delights (or The Millennium)[1] is a fully mature work of intricate complexity. The triptych depicts several biblical and heretical scenes that illustrate the history of mankind according to medieval Christian doctrine.

Life

Hieronymus Bosch was born Jheronimus (or Jeroen) van Aken (meaning "from Aachen"). He signed a number of his paintings as Bosch (pronounced Boss in Dutch). The name derives from his birthplace, 's-Hertogenbosch, which is commonly called "Den Bosch."

Little is known of Bosch’s life or training. He left behind no letters or diaries, and what has been identified has been taken from brief references to him in the municipal records of 's-Hertogenbosch, and in the account books of the local order of the Brotherhood of Our Lady. Nothing is known of his personality or his thoughts on the meaning of his art. Bosch’s date of birth has not been determined with certainty. It is estimated at c. 1450 on the basis of a hand drawn portrait (which may be a self-portrait) made shortly before his death in 1516. The drawing shows the artist at an advanced age, probably in his late sixties.[2]

Bosch was born and lived all his life in and near ‚Äės-Hertogenbosch, the capital of the Dutch province of Brabant. His grandfather, Jan van Aken (died 1454), was a painter and is first mentioned in the records in 1430. It is known that Jan had five sons, four of whom were also painters. Bosch‚Äôs father, Anthonius van Aken (died c. 1478) acted as artistic adviser to the Brotherhood of Our Lady.[3] It is generally assumed that either Bosch‚Äôs father or one of his uncles taught the artist to paint, however none of their works survive.[4] Bosch first appears in the municipal record in 1474, when he is named along with two brothers and a sister.

's-Hertogenbosch, in the south of the present-day Netherlands, was a flourishing city in fifteenth century Brabant. In 1463, 4000 houses in the town were destroyed by a catastrophic fire, which the then (approximately) 13-year-old Bosch may have witnessed. He became a popular painter in his lifetime and often received commissions from abroad. In 1488 he joined the highly respected Brotherhood of Our Lady, an arch-conservative religious group of some 40 influential citizens of 's-Hertogenbosch, and 7,000 'outer-members' from around Europe.

Some time between 1479 and 1481, Bosch married Aleyt Goyaerts van den Meerveen, who was a few years older than the artist. The couple moved to the nearby town of Oirschot, where his wife had inherited a house and land from her wealthy family.[5]

An entry in the accounts of the Brotherhood of Our Lady records Bosch’s death in 1516. A funeral mass served in his memory was held in the church of Saint John on 9th August of that year.[6]

Art

Bosch never dated his paintings and may have signed only some of them (other signatures are certainly not his). Fewer than 25 paintings remain today that can be attributed to him. Philip II of Spain acquired many of Bosch's paintings after the painter's death; as a result, the Prado Museum in Madrid now owns several of his works, including The Garden of Earthly Delights.

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Bosch produced several triptychs. Among his most famous is The Garden of Earthly Delights (or The Millennium)[7] Bosch's masterpiece reveals the artist at the height of his powers; in no other painting does he achieve such complexity of meaning or such vivid imagery.[8] The triptych depicts several biblical and heretical scenes on a grand scale and as a "true triptych," as defined by Hans Belting,[9] was probably intended to illustrate the history of mankind according to medieval Christian doctrine.

This painting depicts paradise with Adam and Eve and many wondrous animals on the left panel, the earthly delights with numerous nude figures and tremendous fruit and birds on the middle panel, and hell with depictions of fantastic punishments of the various types of sinners on the right panel. When the exterior panels are closed the viewer can see, painted in grisaille, God creating the Earth. These paintings have a rough surface from the application of paint; this contrasts with the traditional Flemish style of paintings, in which the smooth surface attempts to hide the fact that the painting is man-made.

The triptych is a work in oil comprising three sections: a square middle panel flanked by rectangular ones that can close over the center as shutters. These outer wings, when folded shut, display a grisaille painting of the earth during the Creation. The three scenes of the inner triptych are probably intended to be read chronologically from left to right. The left panel depicts God presenting to Adam the newly created Eve. The central panel is a broad panorama of sexually engaged nude figures, fantastical animals, oversized fruit, and hybrid stone formations. The right panel is a hellscape and portrays the torments of damnation.

Art historians and critics frequently interpret the painting as a didactic warning on the perils of life's temptations.[10] However, the intricacy of its symbolism, particularly that of the central panel, has led to a wide range of scholarly interpretations over the centuries.[11] Twentieth-century art historians are divided as to whether the triptych's central panel is a moral warning, or a panorama of paradise lost. American writer Peter S. Beagle describes it as an "erotic derangement that turns us all into voyeurs, a place filled with the intoxicating air of perfect liberty."[12]

Generally, the work is described as a warning against lust, and the central panel as a representation of the transience of worldly pleasure. In 1960, the art historian Ludwig von Baldass wrote that Bosch shows "how sin came into the world through the Creation of Eve, how fleshly lusts spread over the entire earth, promoting all the Deadly Sins, and how this necessarily leads straight to Hell".[13] De Tolnay wrote that the center panel represents "the nightmare of humanity," where "the artist's purpose above all is to show the evil consequences of sensual pleasure and to stress its ephemeral character".[14] Supporters of this view hold that the painting is a sequential narrative, depicting mankind's initial state of innocence in Eden, followed by the subsequent corruption of that innocence, and finally its punishment in Hell. At various times in its history, the triptych has been known as La Lujuria, The Sins of the World and The Wages of Sin.

Proponents of this idea point out that moralists during Bosch's era believed that it was woman's‚ÄĒultimately Eve's‚ÄĒtemptation that drew men into a life of lechery and sin. This would explain why the women in the center panel are very much among the active participants in bringing about the fall. At the time, the power of femininity was often rendered by showing a female surrounded by a circle of males. A late fifteenth-century engraving by Israhel van Meckenem shows a group of men prancing ecstatically around a female figure. The Master of the Banderoles's 1460 work the Pool of Youth similarly shows a group of females standing in a space surrounded by admiring figures.

Writing in 1969, E. H Gombrich drew on a close reading of Genesis and the Gospel According to Saint Matthew to suggest that the central panel is, according to Linfert, "the state of mankind on the eve of the Flood, when men still pursued pleasure with no thought of the morrow, their only sin the unawareness of sin."

Interpretation

In earlier centuries it was often believed that Bosch’s art was inspired by medieval heresies and obscure hermetic practices. Others thought that his work was created merely to titillate and amuse, much like the "grotteschi" of the Italian Renaissance. While the art of the older masters was based in the physical world of everyday experience, Bosch confronts his viewer with, in the words of the art historian Walter Gibson, "a world of dreams [and] nightmares in which forms seem to flicker and change before our eyes."

In the first known account of Bosch’s paintings, in 1560 the Spaniard Felipe de Guevara wrote that Bosch was regarded merely as "the inventor of monsters and chimeras." In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch art historian Karel van Mander described Bosch’s work as comprising "wondrous and strange fantasies," however he concluded that the paintings are "often less pleasant than gruesome to look at."[15]

In the twentieth century, scholars have come to view Bosch’s vision as less fantastic, and accepted that his art reflects the orthodox religious belief systems of his age. His depictions of sinful humanity, his conceptions of Heaven and Hell are now seen as consistent with those of late medieval didactic literature and sermons. Most writers attach a more profound significance to his paintings than had previously been supposed, and attempt to interpret it as an expression of a late medieval morality. It is generally accepted that Bosch’s art was created to teach specific moral and spiritual truths, and that the images rendered have precise and premeditated significance. According to Dirk Bax, Bosch’s paintings often represent visual translations of verbal metaphors and puns drawn from both biblical and folkloric sources.[16]

Legacy

Some writers see Bosch as a proto-type medieval surrealist, and parallels are often made with the twentieth century Spanish artist Salvador Dali. Other writers attempt to interpret his imagery using the language of Freudian psychology. However, such theses require a translation of the symbolic system of Medieval Christianity to that of the modern age; according to Gibson, "what we choose to call the libido was denounced by the medieval church as original sin; what we see as the expression of the subconscious mind was for the Middle Ages the promptings of God or the Devil."[17]

Debates on attribution

The exact number of Bosch's surviving works has been a subject of considerable debate. He signed only seven of his paintings, and there is uncertainty whether all the paintings once ascribed to him were actually from his hand. It is known that from the early sixteenth century onwards numerous copies and variations of his paintings began to circulate. In addition, his style was highly influential, and was widely imitated by his numerous followers.[18]

Over the years, scholars have attributed to him fewer and fewer of the works once thought to be his, and today only 25 are definitively ascribed to him. When works come up for auction, they are sometimes attributed to Hieronymus Bosch Workshop.

Works

Many of the works of the early Netherlandish artist Hieronymus Bosch, a partial list of which is provided here with current locations, have been given multiple names when translated.

Paintings

A

- Adoration of the Child

- Allegory of Gluttony and Lust

- Allegory of Intemperance Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

- Ascent of the Blessed

C

- Christ Carrying the Cross (1480s) Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Christ Carrying the Cross (1515-1516)

- Christ Carrying the Cross (Madrid version)

- Christ Child with a Walking Frame

- Christ Crowned with Thorns (1495-1500) (Christ Mocked) National Gallery, London

- Christ Crowned with Thorns (El Escorial version)

- The Conjurer (painting) Saint-Germaine-en-Laye

- Crucifixion With a Donor

- The Crucifixion of Saint Julia

D

- Death of the Miser The National Gallery, Washington, DC.

- Death of the Reprobate]

E

- Ecce Homo (1490s) Stadel Museum, Frankurt, Germany

- Ecce Homo (Hieronymus Bosch)

- The Epiphany (Bosch triptych)

- Epiphany (Bosch painting)

- The Extraction of the Stone of Madness (The Cure of Folly) Museo del Prado, Madrid

F

- Fall of the Damned

G

- The Garden of Earthly Delights Prado, Madrid

H

- The Haywain Triptych Prado, Madrid

- Head of a Halberdier

- Head of a Woman

- Hell (Bosch)

- The Hermit Saint

L

- The Last Judgment (Bosch triptych fragment)

- The Last Judgment (Bosch triptych) Akademie der Bildenden K√ľnste, Vienna

M

- The Marriage Feast at Cana (Bosch) Rotterdam

- Man with a Cask fragment, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.

P

- Paradise and Hell Prado, Madrid

S

- The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things

- Ship of Fools (painting) Louvre, Paris

- Saint Christopher Carrying the Christ Child

- Saint Jerome at Prayer

- Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness

- Saint John the Evangelist on Patmos Gemaldegalerie in Berlin

T

- Terrestrial Paradise (Bosch)

- The Temptation of Saint Anthony (Bosch painting)

- The Temptation of Saint Anthony The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- Two Male Heads

W

- The Wayfarer

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Fr√§nger, 8.

- ‚ÜĎ Walter S. Gibson. Hieronymus Bosch. (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2001), 15-16.

- ‚ÜĎ Gibson, 15, 17.

- ‚ÜĎ Gibson, 19.

- ‚ÜĎ Paul Valery, "The Phase of Doubt, A Critical Reflection." in Robert L. Delevoy. Bosch: Biographical and Critical Study, translated by Stuart Gilbert. (Lausanne: Skira, 1960)

- ‚ÜĎ Gibson, 18.

- ‚ÜĎ Fr√§nger, 8.

- ‚ÜĎ Bosing, 60.

- ‚ÜĎ A "true triptych," or "world triptych," is generally considered one which addresses the history and fate of humanity. Belting, 85.

- ‚ÜĎ Kleiner & Mamiya, 564.

- ‚ÜĎ Snyder 1977, 100.

- ‚ÜĎ Belting, 7.

- ‚ÜĎ von Baldass, 84.

- ‚ÜĎ Glum, 1976.

- ‚ÜĎ Gibson, 9.

- ‚ÜĎ Dirk Bax. Hieronymus Bosch: his picture-writing deciphered. (Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema [1949]; Montclair, NJ: Distributed in North America by Abner Schram, 1979)

- ‚ÜĎ Gibson, 12.

- ‚ÜĎ Gibson, 163.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bax, Dirk. Hieronymus Bosch: his picture-writing deciphered. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema; Montclair, NJ: Distributed in North America by Abner Schram, 1979. ISBN 9789061910206

- Delevoy, Robert L. Bosch: Biographical and Critical Study, translated by Stuart Gilbert. Lausanne: Skira, 1960.

- Gibson, Walter S. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2001. ISBN 9780500201343

- Koldeweij, Jos & Bernard Vermet & Barbera van Kooij: Hieronymus Bosch. New Insights Into His Life and Work. NAi Publishers, Rotterdam 2001. ISBN 9789056622145

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2024.

- Hieronymous Bosch's Seven Deadly Sins table painting Analysis by Anja Zeidler.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Hieronymus_Bosch  history

- The_Garden_of_Earthly_Delights  history

- Works_of_Hieronymus_Bosch  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.