Galactosemia

| Galactosemia Classification and external resources | |

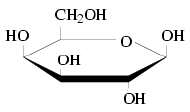

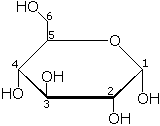

| Galactose | |

| ICD-10 | E74.2 |

| ICD-9 | 271.1 |

| eMedicine | ped/818Â |

| MeSH | D005693 |

Galactosemia is a rare genetic metabolic disorder that affects an individual's ability to properly metabolize the sugar galactose. The disease was first described in 1917 by a German scientist (Goppert 1917), and its cause as a defect in galactose metabolism was identified by a group led by Herman Kalckar in 1956 (Isselbacher et al. 1956). Incidence of the most common or classic type of galactosemia is about one per 62,000 births (The Merck Manual).

Much more serious than lactose intolerance, which prevents the body from getting any nutrition from lactose, galactosemia involves a failure to process a sugar that is already midstream in the metabolic cycle and will only continue to accumulateâand thereby to disrupt essential biochemical processesâso long as lactose or any other galactose source is ingested. Treatment requires eliminating all sources of galactose from the diet. Mortality in untreated galactosemic infants is about 75 percent within two week after birth. Galactosemic children are prone to such effects as mental retardation, speech abnormality, cataracts, and enlarged liver. Screening of newborn children by a simple blood test followed by proper regulation of diet can prevent serious consequences.

Cause

Normally, lactose in food (such as dairy products) is broken down by the body into glucose and galactose, and galactose is then further converted to glucose. In individuals with galactosemia, one of the three types of enzyme needed for further metabolism of galactose is severely diminished or missing entirely due to a defect in the gene for making the affected enzyme. This disruption of the process for converting galactose to glucose leads to the build up of toxic levels of galactose in the blood, resulting in hepatomegaly (an enlarged liver), cirrhosis, renal failure, cataracts, and brain damage.

The genes for making each of the three galactose-processing enzymes are recessive, meaning that a person with only one of the defective genes will be symptom free. Only if a person receives two genes defective for the same enzyme will the person experience galactosemia. If both parents, for example, would have one defective gene for the same galactose-processing enzyme, they would be symptom free, but there would be one chance in four or their conceiving a galactosemic child.

Biochemistry

The fourth carbon on galactose has an axial hydroxyl (-OH) group. This causes galactose to favor the open form as it is more stable than the closed form. This leaves an aldehyde (O=CH-) group available to react with nucleophiles, particularly proteins which contain amino (-NH2) groups, in the body. If galactose accumulates in the body due to flawed enzymatic breakdown, the excess galactose engages in uncontrolled glycolation reactions with proteins, which causes disease by altering the structure of proteins in ways that were not intended for biochemical processes.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Infants are now routinely screened for galactosemia in the United States, and the diagnosis is made while the person is still an infant.

The only treatment for classic galactosemia is eliminating lactose and galactose from the diet. Even with an early diagnosis and a restricted diet, however, some individuals with galactosemia experience long-term complications.

Galactosemia is sometimes confused with lactose intolerance, but galactosemia is a more serious condition. Lactose intolerant individuals have an acquired or inherited shortage of the enzyme lactase, and experience abdominal pains after ingesting dairy products, but no long-term effects. In contrast, galactosemic individuals who consume galactose can cause permanent damage to their bodies.

Types

The process of converting galactose to glucose involves reactions with three different enzymes in sequence. A defect in the production of any one of the three enzymes causes galactosemia, but because their reactions occur sequentially a defect in each one causes a different kind of galactosemia.

The most common type and the first to be discovered is called Galactosemia I or Type I galactosemia. This was the clinically recognized form, the so-called classic galactosemia or profound transferase deficiency, that was first reported by Goppert (1917). It involves a defect in the first of the three enzymes, Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyl transferase (GALT). Untreated galactose I is characterized by poor growth in children, mental retardation, speech abnormality, vision impairment (due to formation of cataract), and liver enlargement (which may be fatal). Strict removal of galactose from diet is required.

Newborns with galactosemia I begin to show symptoms as soon as they begin to drink milk. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, fatique, lethargy, jaundice (a yellowing of the eyes and skin), cataracts growing on the eyes, and enlarged liver. Although people may be diagnosed soon after birth with Galactosemia I and maintained on strict diet into adulthood, they may still experience such abnormalities as slurred speech, female infertility, behavior disorder, and learning disabilities.

Persons with two recessive genes for making the second enzyme galactokinase (GALK) will have Galactosemia II (or Type II Galactosemia). It is less common and less severe than Galactosemia I, and generally does not cause neurological disturbance or liver damage, although untreated children will develop cataracts.

Galactosemia III is caused by a having a defect in the third enzyme, uridyl diphosphogalactose-4-epimerase (GALE). This type of galactosemia is of two forms: a benign form that has no symptoms and permits the person to avoid a special diet; and a severe form, which is extremely rare, with only two reported cases up to 1997. Infants with the benign form of Galactosemia III would be identified in initial screening as having galactosemia and would only be differentiated as having the benign form of galactosemia III through tests that would show levels in the blood of the enzymes GALT and GALK to be in the acceptable range (Longe 2006).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Goppert, F. 1917. Galaktosurie nach Milchzuckergabe bei angeborenem, familiaerem chronischem Leberleiden. Klin Wschr 54:473-477.

- Isselbacher, K. J., E. P. Anderson, K. Kurahashi, and H. M. Kalckar. 1956. Congenital galactosemia, a single enzymatic block in galactose metabolism. Science 13(123): 635-636. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- Longe, J. L., Ed. 2006. The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414403682.

- Openo, K. K., J. M. Schulz, and C. A. Vargas. 2006. Epimerase-deficiency galactosemia is not a binary condition. Am J Hum Genet. 78(1): 89â102. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- The Merck Manual. Carbohydrate metabolism disordersâGalactosemia. Merck Manual. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.