Enlil

Enlil (EN = Lord+ LIL = Air, "Lord of the Wind")[1] was the name of a major Mesopotamian deity. In early Sumerian inscriptions he is portrayed as the primary deity and king of the gods. Enlil was the god of the sky and the earth, the father of the Moon god Sin (Nanna), and the grandfather of the great goddess Ishtar (Inanna). His primary consort was the grain and fertility goddess Ninlil (Lady of the Air), also known as Sud. Originally centered in the city of Nippur, Enlil rose to more universal prominence as a member of the triad of Babylonian gods, together with An (Anu) and Enki (Ea).

At one time, Enlil held possession of the Tablets of Destiny giving him great power over the cosmos and mankind. Although sometimes kindly, he had a stern and wrathful side. As the god of weather, it was he who sent the Great Flood which destroyed all mankind with the exception of Utnapishtim (Atrahasis) and his family.

Enlil appears frequently in ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, Hittite, Canaanite, and other Mesopotamian clay and stone tablets. His name was sometimes rendered as Ellil in later Akkadian, Hittite, and Canaanite literature.

As a member of the great triad of gods, Enlil was in charge of the skies and the earth, while Enki/Ea governed the waters, and An/Anu ruled the deep heavens. However, in later Babylonian mythology, it was the younger storm god Marduk who came to hold the Tablets of Destiny and rule as king of the gods, while the triad retired to a more distant location in the cosmos.

Cultural history

Enlil's commands are by far the loftiest, his words are holy, his utterances are immutable! The fate he decides is everlasting, his glance makes the mountains anxious... All the gods of the earth bow down to father Enlil, who sits comfortably on the holy dais, the lofty dais... whose lordship and princeship are most perfect. The Anunaki gods enter before him and obey his instructions faithfully.—Enlil in the Ekur.[2]

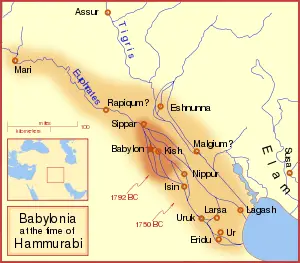

At a very early period, even prior to 3000 B.C.E., Nippur had become the center of an important political district. Inscriptions found during extensive excavations, carried on 1888–1900 by John P. Peters and John Henry Haynes under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania, show that Enlil was the head of an extensive pantheon. Among the titles accorded to him are "king of lands," "king of heaven and earth," and "father of the gods."

His chief temple at Nippur was known as Ekur, signifying "House of the mountain." The sanctity acquired by this edifice was such that Babylonian and Assyrian rulers vied with one another in embellishing and restoring Enlil's seat of worship. The word Ekur became the designation of a temple in general.

Grouped around Enlil's main sanctuary, there arose temples and chapels to the gods and goddesses who formed his court, so that Ekur became the name for an entire sacred precinct in the city of Nippur. The name "mountain house" suggests a lofty structure and was perhaps the designation originally of the staged tower at Nippur, built in imitation of a mountain, with the sacred shrine of the god on the top.

Enlil in mythology

| Fertile Crescent myth series | |

|---|---|

| Mesopotamian | |

| Levantine | |

| Arabian | |

| Mesopotamia | |

| Primordial beings | |

| The great gods | |

| Demigods & heroes | |

| Spirits & monsters | |

| Tales from Babylon | |

| 7 Gods who Decree | |

|

4 primary: |

3 sky: |

One story names Enlil's origins in the union of An, the god of the deepest heavens, and Ki, the goddess of the Earth. Rather than emerging from Ki's womb, however, Enlil came into existence out of the exhausted breath of the primordial couple.

Creator of heaven, earth, and seasons

According to ancient myths, heaven and earth were inseparable before Enlil split them in two. His father An carried away heaven, while his mother Ki, in company with Enlil, took the earth. In this context, Enlil was also known as the inventor of the pickaxe/hoe (favorite tool of the Sumerians) who caused plants to grow and mankind to be born.[3] After cleaving the heavens from the earth, Enlil created the pickaxe and broke up earth's crust. It was this act that caused human beings to spring from the earth.

As the Lord of the Winds, Enlil had charge of both the great storms and the kindly winds of spring, which came forth at his command from his mouth and nostrils.[4] A text called The Debate between Winter and Summer describes Enlil as mating with the hills to produce the two seasons, Emesh ("Summer") and Enten ("Winter"):

Enlil set his foot upon the earth like a great bull. Enlil, the king of all lands, set his mind to increasing the good day of abundance, to making the... night resplendent in celebration, to making flax grow, to making barley proliferate, to guaranteeing the spring floods at the quay... He copulated with the great hills, he gave the mountain its share. He filled its womb with Summer and Winter, the plenitude and life of the Land. As Enlil copulated with the earth, there was a roar like a bull's. The hill spent the day at that place and at night she opened her loins. She bore Summer and Winter as smoothly as fine oil.

Author of the Great Flood

Enlil embodied power and authority. In several myths he is described as stern and wrathful, as opposed to his half-brother Enki/Ea, who showed more compassion and sometimes risked Enlil's disapproval in siding with mankind or other gods. Enki risked Enlil's anger in order to save humanity from the Great Flood that Enlil had designed. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enlil sets out to eliminate humanity, whose overpopulation and resultant mating noise is offensive to his ears. Enlil convenes a council of the gods and convinces them to promise not to tell humankind that he plans their total annihilation. Enki, however, tells the divine secret to the walls of Utnapishtim's reed hut. He thus covertly rescues Utnapishtim (elsewhere called Atrahasis) by instructing him to build a boat for his family and animals. Enlil is angry that his will has been thwarted, but Enki argues that Enlil is unfair to punish the guiltless Utapishtim. The goddess Ishtar joins Enki and repents in tears for her own role in supporting Enlil's plan to destroy humankind. Enlil promises that the gods will not attempt to eliminate mankind again if humans will practice birth control and live in harmony with the natural world.

Enlil is also a god of order, while Enki is more willing to bend the rules. In another myth, the whole of mankind once worshiped Enlil with one tongue, but Enki caused a profusion of languages, and thus many different traditions of worship.

Father of gods

When Enlil was a young god, he was banished from Dilmun, the home of the gods, to the Underworld, for raping the his future consort, the young grain goddess Ninlil.

Enlil said to her, "I want to kiss you!" but he could not make her let him. "My vagina is small, it does not know pregnancy. My lips are young, they do not know kissing," (she said)... Father Enlil, floating downstream—he grasped hold of her whom he was seeking. He was actually to have intercourse with her, he was actually to kiss her! ...At this one intercourse, at this one kissing, he poured the seed of (the Moon god) Suen into her womb."

She conceived a boy, the future Moon god Nanna (Sin/Suen). After Ninlil followed him to the underworld, Enlil disguised himself as the "gatekeeper" and impregnated her again, whereupon she gave birth to their son Nergal, the god of death. After this, Enlil disguised himself as the "man of the river of the nether world" and conceived with her the underworld god Ninazu, although other traditions say this deity is the child of Ereshkigal and Gugalana. Later, Enlil disguised himself as the "man of the boat," impregnating her with Enbilulu, god of rivers and canals. With the underworld goddess Ereshkigal, Enlil was father of Namtar the god of diseases and demons. After fathering these underworld deities, Enlil was allowed to return to Dilmun and resume his position as god of the skies and the earth.

In another version of the story of his relationship with Ninlil, Enlil treats her more honorably. When she spurns his initial advances, he begs for her hand in marriage, offering great honors for her to become his queen.[5]

Replaced by Marduk

In later Babylonian religion, Enlil was replaced by Marduk as the king of the gods. In the Enuma Elish, after his cosmic victory over the primeval sea goddess Tiamat, Marduk "stretched the immensity of the firmament... and Anu and Enlil and Ea had each their right stations."

Thus banished to a distant corner of the cosmos, Enlil nevertheless continued to be venerated until approximately 1000 B.C.E. as the high god of Nippur, while his granddaughter Ishtar was the major female god in the Mesopotamian pantheon. He would be honored throughout the Babylonian and later Persian empires for several more centuries as a member of the great, if far away, triad of deities together with Anu and Ea.

Enlil's legacy

Like his counterparts Anu and Enki/Ea, several of Enlil's characteristics formed the theological background of later Canaanite and Israelite traditions. The Hebrew patriarch Abraham was said to have come from "Ur of the Chaldeans," directly downriver from Nippur, where Enlil's center of worship lay. Abraham's family certainly knew the stories of Enlil, Anu, and Enki. While Abraham rejected the polytheism of Babylonian religion, certain stories involving Enlil seem to have found their way into Israelite tradition. The clearest of these is the story of Enlil sending the Great Flood to destroy mankind. However, in the Hebrew version, there is only one God; and thus Yahweh is both the originator of the flood (Enlil's role) and the deity who warns Noah of its coming (Enki's role).

As Ellil, Enlil may have been influenced the development of the concept of El, the head of the assembly of the gods in Canaanite religion, and the object of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob's devotion in the Hebrew Bible. Some scholars have seen a parallel between Marduk's rise to the kingship of the gods over Enlil and the older gods in Babylonian mythology and Yahweh's rise in Israelite tradition. As the sky deity and earlier king of the gods, Enlil may also have influenced the Greek concept of Zeus, although it was Marduk who was directly associated with the planet Jupiter.

Notes

- ↑ John A. Halloran, December 10th, 2006, "Sumerian Lexicon: Version 3.0" www.sumerian.org. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ Enlil-A www.piney.com.

- ↑ Hooke, 2004.

- ↑ Translation of Enlil and Ninlil etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ Enlil and Sud etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain. The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. Cuneiform monographs, 23. Leiden: Brill, 2003. ISBN 978-9004130241

- Gibson, McGuire. Nippur, sacred city of Enlil, supreme god of Sumer and Akkad. Chicago, Ill: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, 1997. OCLC 44374886

- Hooke. S.H. Middle Eastern Mythology, Dover Publications, 2013 (original 2004). ISBN 978-0486435510

- McCall, Henrietta. Mesopotamian Myths. The Legendary past. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0292751309

- Schomp, Virginia. The Ancient Mesopotamians. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, 2009. ISBN 978-0761430957

External links

All links retrieved February 13, 2024.

- "Enlil and Ninlil" etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.