Diesel

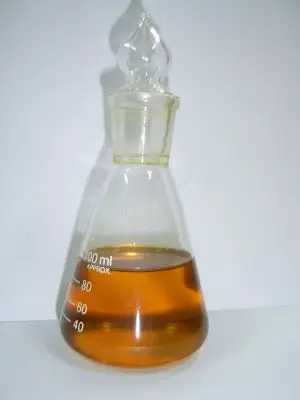

Diesel, or diesel fuel, is any fuel that is used to operate a diesel engine. Most commonly, it refers to a specific liquid fuel obtained by the fractional distillation of petroleum, often called petrodiesel. Alternative diesel fuels not derived from petroleum are biodiesel and biomass to liquid (BTL) or gas to liquid (GTL) diesel. Ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD) is a standard for defining diesel fuel with substantially lowered sulfur content. Diesel fuel is widely used for most types of transportation, other than the gasoline-powered passenger automobile.

History

Etymology

The word "diesel" is derived from the German inventor Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel who in 1892 invented the diesel engine.

Diesel engine

Diesel engines are a type of internal combustion engine. Rudolf Diesel originally designed the diesel engine to use coal dust as a fuel. He also experimented with various oils, including some vegetable oils,[1] such as peanut oil, which was used to power the engines that he exhibited at the 1900 Paris Exposition and the 1911 World's Fair in Paris.[2]

Sources

Diesel fuel is produced from petroleum and from various other sources. The resulting products are mostly interchangeable in most applications.

Petroleum diesel

Refining

Petroleum diesel, also called petrodiesel,[3] or fossil diesel is produced from petroleum and is a hydrocarbon mixture, obtained in the fractional distillation of crude oil between 200 °C and 350 °C at atmospheric pressure.

Fuel value and price

The density of petroleum diesel is about 0.85 kg/l (7.09 lbs/gallon(us)), about 18 percent more than petrol (gasoline), which has a density of about 0.72 kg/l (6.01 lbs/gallon(us)). When burnt, diesel typically releases about 38.6 MJ/l (138,700 BTU per US gallon), whereas gasoline releases 34.9 MJ/l (125,000 BTU per US gallon), 10 percent less[4] by energy density, but 45.41 MJ/kg and 48.47 MJ/kg, 6.7 percent more by specific energy. Diesel is generally simpler to refine from petroleum than gasoline. The price of diesel traditionally rises during colder months as demand for heating oil rises, which is refined in much the same way. Due to its higher level of pollutants, diesel must undergo additional filtration which contributes to a sometimes higher cost. In many parts of the United States and throughout the UK and Australia[5] diesel may be higher priced than petrol.[6] Reasons for higher priced diesel include the shutdown of some refineries in the Gulf of Mexico, diversion of mass refining capacity to gasoline production, and a recent transfer to ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD), which causes infrastructural complications.

Use as vehicle fuel

Unlike Petroleum ether and Liquefied petroleum gas engines, diesel engines do not use high voltage spark ignition (spark plugs). An engine running on diesel compresses the air inside the cylinder to high pressures and temperatures (compression ratios from 15:1 to 21:1 are common); the diesel is generally injected directly into the cylinder near the end of the compression stroke. The high temperatures inside the cylinder causes the diesel fuel to react with the oxygen in the mix (burn or oxidize), heating and expanding the burning mixture in order to convert the thermal/pressure difference into mechanical work; i.e., to move the piston. (Glow plugs are used to assist starting the engine to preheat cylinders to reach a minimum operating temperature.) High compression ratios and throttleless operation generally result in diesel engines being more efficient than many spark-ignited engines.

This and being less flammable and explosive than gasoline are the main reasons for military use of diesel in armored fighting vehicles like tanks and trucks. Engines running on diesel also provide more torque and are less likely to stall as they are controlled by a mechanical or electronic governor. A disadvantage of diesel as a vehicle fuel in some climates, compared to gasoline or other petroleum derived fuels, is that its viscosity increases quickly as the fuel's temperature decreases, turning into a non-flowing gel at temperatures as high as -19 °C (-2.2 °F) or -15 °C (+5 °F), which can't be pumped by regular fuel pumps. Special low temperature diesel contains additives that keep it in a more liquid state at lower temperatures, yet starting a diesel engine in very cold weather still poses considerable difficulties.

Another rare disadvantage of diesel engines compared to petrol/gasoline engines is the possibility of runaway failure. Since diesel engines do not require spark ignition, they can sustain operation as long as diesel fuel is supplied. Fuel is typically supplied via a fuel pump. If the pump breaks down in an "open" position, the supply of fuel will be unrestricted and the engine will runaway and risk terminal failure.

Use as car fuel

Diesel-powered cars generally have a better fuel economy than equivalent gasoline engines and produce less greenhouse gas emission. Their greater economy is due to the higher energy per-liter content of diesel fuel and the intrinsic efficiency of the diesel engine. While petrodiesel's higher density results in higher greenhouse gas emissions per liter compared to gasoline,[7] the 20–40 percent better fuel economy achieved by modern diesel-engined automobiles offsets the higher-per-liter emissions of greenhouse gases, and produces 10-20 percent less greenhouse gas emissions than comparable gasoline vehicles.[8] Biodiesel-powered diesel engines offer substantially improved emission reductions compared to petro-diesel or gasoline-powered engines, while retaining most of the fuel economy advantages over conventional gasoline-powered automobiles.

Reduction of sulfur emissions

In the past, diesel fuel contained higher quantities of sulfur. European emission standards and preferential taxation have forced oil refineries to dramatically reduce the level of sulfur in diesel fuels. In the United States, more stringent emission standards have been adopted with the transition to ULSD starting in 2006 and becoming mandatory on June 1, 2010 (see also diesel exhaust). U.S. diesel fuel typically also has a lower cetane number (a measure of ignition quality) than European diesel, resulting in worse cold weather performance and some increase in emissions.[9] This is one reason why U.S. drivers of large trucks have increasingly turned to biodiesel fuels with their generally higher cetane ratings.

Environment hazards of sulfur

High levels of sulfur in diesel are harmful for the environment because they prevent the use of catalytic diesel particulate filters to control diesel particulate emissions, as well as more advanced technologies, such as nitrogen oxide (NOx) adsorbers (still under development), to reduce emissions. However, the process for lowering sulfur also reduces the lubricity of the fuel, meaning that additives must be put into the fuel to help lubricate engines. Biodiesel and biodiesel/petrodiesel blends, with their higher lubricity levels, are increasingly being utilized as an alternative. The U.S. annual consumption of diesel fuel in 2006 was about 190 billion liters (42 billion imperial gallons or 50 billion US gallons).[10]

Chemical composition

Petroleum-derived diesel is composed of about 75 percent saturated hydrocarbons (primarily paraffins including n, iso, and cycloparaffins), and 25 percent aromatic hydrocarbons (including naphthalenes and alkylbenzenes).[11] The average chemical formula for common diesel fuel is C12H23, ranging from approx. C10H20 to C15H28.

Algae, microbes, and water

There has been much discussion and misinformation about algae in diesel fuel. Algae require sunlight to live and grow. As there is no sunlight in a closed fuel tank, no algae can survive there. However, some microbes can survive there, and can feed on the diesel fuel.

These microbes form a colony that lives at the fuel/water interface. They grow quite rapidly in warmer temperatures. They can even grow in cold weather when fuel tank heaters are installed. Parts of the colony can break off and clog the fuel lines and fuel filters.

It is possible to either kill this growth with a biocide treatment, or eliminate the water, a necessary component of microbial life. There are a number of biocides on the market, which must be handled very carefully. If a biocide is used, it must be added every time a tank is refilled until the problem is fully resolved.

Biocides attack the cell wall of microbes resulting in lysis, the death of a cell by bursting. The dead cells then gather on the bottom of the fuel tanks and form a sludge, filter clogging will continue after biocide treatment until the sludge has abated.

Given the right conditions microbes will repopulate the tanks and re-treatment with biocides will then be necessary. With repetitive biocide treatments microbes can then form resistance to a particular brand. Trying another brand may resolve this.

Road hazard

Petrodiesel spilled on a road will stay there until washed away by sufficiently heavy rain, whereas gasoline will quickly evaporate. After the light fractions have evaporated, a greasy slick is left on the road which can destabilize moving vehicles. Diesel spills severely reduce tire grip and traction, and have been implicated in many accidents. The loss of traction is similar to that encountered on black ice. Diesel slicks are especially dangerous for two-wheeled vehicles such as motorbikes.

Synthetic diesel

Wood, hemp, straw, corn, garbage, food scraps, and sewage-sludge may be dried and gasified to synthesis gas. After purification the Fischer-Tropsch process is used to produce synthetic diesel.[12] This means that synthetic diesel oil may be one route to biomass based diesel oil. Such processes are often called biomass-to-liquids or BTL.

Synthetic diesel may also be produced out of natural gas in the gas-to-liquid (GTL) process or out of coal in the coal-to-liquid (CTL) process. Such synthetic diesel has 30 percent lower particulate emissions than conventional diesel (US- California).

Biodiesel

Biodiesel can be obtained from vegetable oil (vegidiesel/vegifuel), or animal fats (bio-lipids), using transesterification. Biodiesel is a non-fossil fuel, cleaner burning alternative to petrodiesel. It can also be mixed with petrodiesel in any amount in some modern engines,[13] but is 'strongly recommended against' by some manufacturers.[14] Biodiesel has a higher gel point than petrodiesel, but is comparable to diesel. This can be overcome by using a biodiesel/petrodiesel blend, or by installing a fuel heater, but this is only necessary during the colder months. A small fraction of biodiesel can be used as an additive in low-sulfur formulations of diesel to increase the lubricity lost when the sulfur is removed. In the event of fuel spills, biodiesel is easily washed away with ordinary water and is nontoxic compared to other fuels.

Biodiesel can be produced using kits. Certain kits allow for processing of used vegetable oil that can be run through any conventional diesel motor with modifications. The modification needed is the replacement of fuel lines from the intake and motor and all affected rubber fittings in injection and feeding pumps a.s.o (in vehicles manufactured before 1993). This is because biodiesel is an effective solvent and will replace softeners within unsuitable rubber with itself over time. Synthetic gaskets for fittings and hoses prevent this.

Chemically, most biodiesel consists of alkyl (usually methyl) esters instead of the alkenes and aromatic hydrocarbons of petroleum derived diesel. However, biodiesel has combustion properties very similar to petrodiesel, including combustion energy and cetane ratings. Paraffin biodiesel also exists. Due to the purity of the source, it has a higher quality than petrodiesel.

Biodiesel emissions

The use of biodiesel blended diesel fuels in fractions up to 99 percent result in substantial emission reductions. Sulfur oxide and sulfate emissions, major components of acid rain, are essentially eliminated with pure biodiesel and substantially reduced using biodiesel blends with minor quantities of ULSD petrodiesel. Use of biodiesel also results in substantial reductions of unburned hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter compared to either gasoline or petrodiesel. CO, or carbon monoxide, emissions using biodiesel are substantially reduced, on the order of 50 percent compared to most petrodiesel fuels. The exhaust emissions of particulate matter from biodiesel have been found to be 30 percent lower than overall particulate matter emissions from petrodiesel. The exhaust emissions of total hydrocarbons (a contributing factor in the localized formation of smog and ozone) are up to 93 percent lower for biodiesel than diesel fuel. Biodiesel emissions of nitrogen oxides can sometimes increase slightly. However, biodiesel's complete lack of sulfur and sulfate emissions allows the use of NOx control technologies, such as AdBlue, that cannot be used with conventional diesel, allowing the management and control of nitrous oxide emissions.

Biodiesel also may reduce health risks associated with petroleum diesel. Biodiesel emissions showed decreased levels of PAH and nitrated PAH compounds which have been identified as potential cancer causing compounds. In recent testing, PAH compounds were reduced by 75 to 85 percent, with the exception of benzo(a)anthracene, which was reduced by roughly 50 percent. Targeted nPAH compounds were also reduced dramatically with biodiesel fuel, with 2-nitrofluorene and 1-nitropyrene reduced by 90 percent, and the rest of the nPAH compounds reduced to only trace levels.[15]

Transportation

Diesel fuel is widely used in most kinds of transportation. The gasoline-powered passenger automobile is the major exception.

Railroads

Diesel-electric locomotives are used predominantly on most railroads worldwide, except in areas such as a high percentage of the European continent where overhead electrification permits use of electric locomotives. Steam locomotives, dominant until the 1950s or 1960s in most regions, are now generally seen only on tourist-oriented historical railroads and special excursion trains.

Aircraft

The first diesel-powered flight of a fixed wing aircraft took place on the evening of September 18, 1928, at the Packard Motor Company proving grounds, Utica, Michigan with Captain Lionel M. Woolson and Walter Lees at the controls (the first "official" test flight was taken the next morning). The engine was designed for Packard by Woolson and the aircraft was a Stinson SM1B, X7654. Later that year Charles Lindbergh flew the same aircraft. In 1929 it was flown 621 miles (999 km) non-stop from Detroit to Langley, Virginia (near Washington, D.C.). This aircraft is presently owned by Greg Herrick and resides in the Golden Wings Flying Museum near Minneapolis, Minnesota. In 1931, Walter Lees and Fredrick Brossy set the nonstop flight record flying a Bellanca powered by a Packard diesel for 84h 32 m. The Hindenburg was powered by four 16-cylinder diesel engines, each with approximately 1,200 horsepower (890 kW) available in bursts, and 850 horsepower (630 kW) available for cruising. Modern diesel engines for propeller-driven aircraft are manufactured by Thielert Aircraft Engines and SMA. These engines are able to run on Jet A fuel, which is similar in composition to automotive diesel and cheaper and more plentiful than the 100 octane low-lead gasoline (avgas) used by the majority of the piston-engine aircraft fleet.

The most-produced aviation diesel engine in history so far has been the Junkers Jumo 205, which, along with its similar developments from the Junkers Motorenwerke, had approximately 1,000 examples of the unique opposed piston, two-stroke design powerplant built in the 1930s leading into World War II in Germany.

Automobiles

The very first diesel-engine automobile trip (inside the United States) was completed on January 6, 1930. The trip was from Indianapolis to New York City, a distance of nearly 800 miles (1,300 km). This feat helped to prove the usefulness of the compression ignition engine.

Automobile racing

In 1931, Dave Evans drove his Cummins Diesel Special to a nonstop finish in the Indianapolis 500, the first time a car had completed the race without a pit stop. That car and a later Cummins Diesel Special are on display at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum.[16]

In the late 1970s, Mercedes-Benz at Nardò drove a C111-III with a 5-cylinder diesel engine to several new records, including driving an average of 314 km/h (195 mph) for 12 hours and hitting a top speed of 325 km/h (201 mph).

With turbocharged diesel cars getting stronger in the 1990s, they were entered in touring car racing, and BMW even won the 24 Hours Nürburgring in 1998 with a 320d.

After winning the 12 Hours of Sebring in 2006 with the diesel-powered R10 TDI LMP, Audi won the 24 Hours of Le Mans, too. This is the first time a diesel-fueled vehicle has won at Le Mans against cars powered with regular fuel or other alternative fuel like methanol or bio-ethanol. French automaker Peugeot entered the diesel powered Peugeot 908 LMP in the 2007 24 Hours of Le Mans in response to the success of the Audi R10 TDI but Audi won the race again and for the third consecutive time in 2008. In 2008 Audi used next generation 10% BTL biodiesel manufactured from biomass.[17]

In an effort to further demonstrate the potential of diesel power, California-based Gale Banks Engineering designed, built and raced a Cummins-powered pickup at the Bonneville Salt Flats in October 2002. The truck set a top speed of 355 km/h (222 mph) and became the world’s fastest pickup, and almost equally notable, the truck drove to the race towing its own support trailer.

On August 23, 2006, the British-based earthmoving machine manufacturer JCB raced the specially designed JCB Dieselmax car at 563.4 km/h (350.1 mph). The driver was Andy Green. The car was powered by two modified JCB 444 diesel engines.

Other important diesel engine performances are the SEAT León TDI's victories in the World Touring Car Championship.

Other uses

Poor quality (high sulfur) diesel fuel has been used as a palladium extraction agent for the liquid-liquid extraction of this metal from nitric acid mixtures. This has been proposed as a means of separating the fission product palladium from PUREX raffinate which comes from used nuclear fuel. In this solvent extraction system the hydrocarbons of the diesel act as the diluent while the dialkyl sulfides act as the extractant. This extraction operates by a solvation mechanism. So far neither a pilot plant nor full scale plant has been constructed to recover palladium, rhodium or ruthenium from nuclear wastes created by the use of nuclear fuel.[18]

Health effects

Diesel combustion exhaust is a major source of atmospheric soot and fine particles, constituting a portion of air pollutants implicated in human heart and lung damage. Diesel exhaust also contains nanoparticles. The study of nanoparticles and nanotoxicology is still in its infancy, and the full health effects from nanoparticles produced by all types of diesel are unknown. At least one study has observed that short-term exposure to diesel exhaust does not result in adverse extra-pulmonary effects, effects that are often correlated with an increase in cardiovascular disease.[19] Long-term effects still need to be clarified, as well as the effects on susceptible groups of people with cardiopulmonary diseases.

It should be noted that the types and quantities of nanoparticles can vary according to operating conditions, such as temperatures, pressures, presence of an open flame, fundamental fuel type and fuel mixture, and even atmospheric mixtures. As such, the types of nanoparticles produced by different engine technologies and even different fuels are not necessarily comparable. In general, the usage of biodiesel and biodiesel blends results in decreased pollution. One study has shown that the volatile component of 95 percent of diesel nanoparticles is unburned lubricating oil.[20]

Taxation

Diesel fuel is very similar to heating oil used for central heating. In Europe, the United States, and Canada, taxes on diesel fuel are higher than on heating oil due to the fuel tax, and in those areas, heating oil is marked with fuel dyes and trace chemicals to prevent and detect tax fraud. Similarly, "untaxed" diesel (sometimes called "off road diesel") is available in the United States, which is available for use primarily in agricultural applications such as fuel for tractors, recreational and utility vehicles or other non-commercial vehicles that do not use public roads. Additionally, this fuel may have sulfur levels that exceed the limits for road use by the 2007 standards. This untaxed diesel is dyed red for identification purposes.[21] Should a person be found using this untaxed diesel fuel for a typically taxed purpose (such as "over-the-road," or driving use), the user may have to pay a heavy fine.

In the United Kingdom, Belgium and the Netherlands it is known as red diesel (or gas oil), and is also used in agricultural vehicles, home heating tanks, refrigeration units on vans/trucks which contain perishable items (e.g. food, medicine) and for marine craft. Diesel fuel, or Marked Gas Oil is dyed green in the Republic of Ireland. The term DERV ("diesel engined road vehicle") is used in the UK as a synonym for unmarked road diesel fuel. In India, taxes on diesel fuel are lower than on petroleum as most vehicles that transport grain and other essential commodities across the country run on diesel.

In Germany, diesel fuel is taxed lower than petroleum but the annual vehicle tax is higher for diesel vehicles than for petroleum vehicles. This gives an advantage to vehicles that travel longer distances (which is the case for trucks and utility vehicles) because the annual vehicle tax depends only on engine displacement, not on distance driven. The point at which a diesel vehicle becomes less expensive than a comparable petroleum vehicle is around 20,000 km per year (12,500 miles per year) for an average car.

Taxes on biodiesel in the United States vary from state to state. Some states (Texas, for example) have no tax on biodiesel and a reduced tax on biodiesel blends.[22] Other states, such as North Carolina, tax biodiesel (in any blended configuration) the same as petrodiesel, although they have introduced new incentives to producers and users of all biofuels.[23]

See also

- Common ethanol fuel mixtures

- Kerosene

- Liquid fuels

- Gasoline gallon equivalent

- Diesel hybrid vehicles

- Comparison of automobile fuel technologies

- List of diesel automobiles

- Turbodiesel

- Dieselization

Notes

- ↑ Alfred Philip Chalkley and Rudolf Diesel, 1913, Diesel Engines for Land and Marine Work. (London, UK: Constable & Co. Ltd.)

- ↑ Ayhan Demirbas, 2008, Biodiesel: A Realistic Fuel Alternative for Diesel Engines. (Berlin, DE: Springer. ISBN 1846289947)

- ↑ Kicking The Gasoline & Petro-Diesel Habit - A Business Manager's Blueprint For Action. macCompanion Magazine.

- ↑ Table B4, Appendix B. Transportation Energy Data Book. Center for Transportation Analysis of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Facts about Diesel Prices. Australian Institute of Petroleum.

- ↑ Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Update. tonto.eia.doe.gov. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Emission Facts: Average Carbon Dioxide Emissions Resulting from Gasoline and Diesel Fuel. US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Diesel cars set to outsell petrol. BBC News. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Idle Hour," Feature Article, January 2005. Mechanical Engineering.

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information. EIA. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Toxicological profile for fuel oils. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Synthetic Diesel May Play a Significant Role as Renewable Fuel in Germany. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service website. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Biodiesel: Homegrown Oil. Mother Earth News. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Also, the Users Manual for Volkswagen 2.0 TDI engines in Australia specifically warns against it; Forum vwwatercooled.org.au. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Pollution: Petrol vs. Hemp. Hempcar.org. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Hall of Fame Museum. Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Audi R10 TDI on next generation Biofuel at Le Mans. Audi Motorsport. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ V.G. Torgov, V.V. Tatarchuk, I.A. Druzhinina, T.M. Korda et al. 1994, "Justification of the choice of an extraction system on the basis of petroleum sulfides for extracting fragment palladium." Atomic Energy. 76(6): 442–448. (Translated from Atomnaya Energiya 76(6): 478–485.

- ↑ Exposure to Diesel Nanoparticles Does Not Induce Blood Hypercoagulability in an at-Risk Population. blackwellpublishing.com.

- ↑ On-line measurements of diesel nanoparticle composition and volatility. dx.doi.org. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Title 26, § 48.4082-1 Diesel fuel and kerosene; exemption for dyed fuel. United States Government Printing Office. "Diesel fuel or kerosene satisfies the dyeing requirement of this paragraph (b) only if the diesel fuel or kerosene contains—(1) The dye Solvent Red 164 (and no other dye) at a concentration spectrally equivalent to at least 3.9 pounds of the solid dye standard Solvent Red 26 per thousand barrels of diesel fuel or kerosene; or (2) Any dye of a type and in a concentration that has been approved by the Commissioner." Cited as 26 CFR 48.4082-1. This regulation implements . Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Texas Biodiesel Laws and Incentives. eere.energy.gov. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ North Carolina Biodiesel Laws and Incentives. eere.energy.gov. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Demirbas, Ayhan. Biodiesel: A Realistic Fuel Alternative for Diesel Engines. Berlin, DE: Springer, 2008. ISBN 1846289947

- Song, Chunsham, Chang S Hsu, and Isao Mochida. Chemistry of Diesel Fuels. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis, 2000. ISBN 1560328452

- Tickell, Joshua, Kaia Tickell, and Kaia Roman. From the Fryer to the Fuel Tank: The Complete Guide to Using Vegetable Oil as an Alternative Fuel. New Orleans, LA: Joshua Tickell Media Productions, 2000. ISBN 0970722702

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.