Black Elk

| Black Elk | |

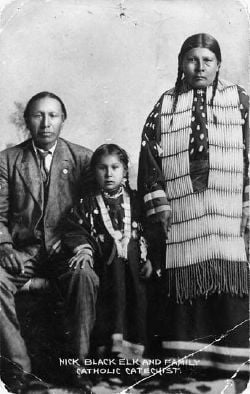

Black Elk with wife and daughter, circa 1890-1910

| |

| Born | 1863 |

|---|---|

| Died | 1950 |

Black Elk (Hehaka Sapa) (c. December 1863 ‚Äď August 19, 1950) was a famous Wichasha Wakan (Medicine man or Holy Man) of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux). He was heyoka and a second cousin of Crazy Horse. Black Elk participated, at about the age of twelve, in the Battle of the Little Bighorn of 1876, and was wounded in the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.

Black Elk married his first wife, Katie War Bonnett, in 1892. She became a Catholic, and all three of their children were baptized in the Catholic faith. After her death in 1903, he too was baptized, taking the name Nicholas Black Elk and serving as a catechist. He continued to serve as a spiritual leader among his people, seeing no contradiction in embracing what he found valid in both his tribal traditions concerning Wakan Tanka, and those of Christianity. He remarried in 1905, to Anna Brings White, a widow with two daughters. She bore him three more children, and remained his wife until she died in 1941.

Toward the end of his life, he revealed the story of his life, and a number of sacred Sioux rituals to John Neihardt and Joseph Epes Brown for publication, and his accounts have won wide interest and acclaim. Black Elk was guided throughout his life by visions, in which he was encouraged and exhorted to help his people. His earliest and guiding vision concluded with the sight of the whole world as one, the hoops of many nations united in one hoop, with one mighty tree sheltering everyone as the children of one father and one mother.

Black Elk remained a devout Catholic throughout the remaining years of his life, walking to church every Sunday, even when he was dying of tuberculosis.

Early life and visions

Black Elk was born into the Oglala Lakota (Sioux Nation) in December 1863, ("Moon of the Popping Trees during the Winter When the Four Crows Were Killed"). When he was three years old, his father was wounded in the Fetterman Fight, known among the Sioux as the Battle of the Hundred Slain, organized by Chief Red Cloud. This was a winter when hunting was poor and snowfall was heavy. Nonetheless, the tribe moved westward, away from white encroachment.

When Black Elk was four years old, he began to hear voices when no one was present, which reportedly frightened him. At the age of five, he had a vision in which two flying men appeared to him, singing a sacred song to the accompaniment of the drumming of thunder. He kept these voices and visions to himself.

In the Native American way of life, young men traditionally go alone into nature for a period of time, fasting, sweating, and practicing traditional religion in the pursuit of a vision (a "vision quest") at the time of initiation into adulthood. However, at a much younger age, Black Elk received a vision without effort on his part. This seems to point to Black Elk having been chosen by the Ancestors for a special mission.

Meeting "the Grandfathers"

At the age of nine, Black Elk had a vision following the instruction of voices telling him to "hurry because his Grandfathers are waiting." His tribe was moving camp at the time, but Black Elk became so sick that he had to be carried. Arms, legs and face swollen, he was laid to recover in his parents' teepee. At this point, looking through the teepee's top opening, he viewed the same men from his earlier vision beckoning him to follow them to his Grandfathers. Then led by horses, he was taken to a teepee in which the six Grandfathers were waiting. Each of the grandfathers told Black Elk something about themselves and the Native peoples' destiny, and each gave him a symbolic object. He was told by the sixth Grandfather that he would receive his power, important for the great trouble to come to his nation.

The vision progressed to four ascents, each one getting progressively steeper and more difficult, which they climbed together. Black Elk reported seeing fighting, gunfire, and smoke, and his people fleeing "like swallows." However, the vision ended with the sight of the whole world as one, the hoops of many nations united in one hoop, with one mighty tree sheltering everyone as the children of one father and one mother. He was then instructed to go back empowered and restore his people.

When Black Elk regained consciousness following this vision, his parents told him that he had been near death for twelve days and the medicine man, Whirlwind Chaser, had cured him. Black Elk was afraid to share his vision, believing he could not adequately convey his experience. However, Whirlwind Chaser told his parents that there was something special about him, leading Black Elk to believe that the medicine man knew he had received such a vision.

Teen years

When Black Elk was eleven years old (1874), his people were camped in the Black Hills of present-day South Dakota. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, had specified the area of the Great Sioux Reservation to be all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River and additional territory in adjoining states. This included the Black Hills. The treaty stipulated that the land was to be "set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation" of the Lakota.

However, after gold was discovered, the U.S. Government violated the treaty and took control of the region. General George Armstrong Custer moved into the Black Hills. Sioux chiefs at that time included Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Crazy Horse, the latter two more resistant and distrusting of the Europeans than Red Cloud was. Crazy Horse, a powerful warrior, was the first chief to come from Black Elk’s family, which had a tradition of holy men. Crazy Horse became a chief due to special power received through a vision.

For some time the Lakota tribes moved around on the Great Reservation, mainly in South Dakota and Montana. Unable to freely practice their traditional way of life, they began practicing the Sun Dance, which was feared by the white man.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

In June 1876 Black Elk's people relocated to a big camp on the shores of the Greasy Grass (Little Big Horn River) in Montana Territory. The encampment was unusually large and included people from various Lakota bands (Oglalas, Brules, Sans Arcs, Minneconjous, and Hunkpapas), Northern Cheyenne, Blackfoot, and a small number of Arapaho. The size of the village is unknown, though is estimated to have been 949 lodges, with between 900 to 1,800 warriors.

While swimming on the afternoon of June 25, word came that U.S. Cavalry were approaching. Pandemonium ensued as General Custer attacked. The battle continued until sundown when the Indians drove the soldiers into the hills and resumed the following day. This historic battle, in which George Armstrong Custer was killed, is famously known as the "Battle of the Little Bighorn," or "Custer's Last Stand." It was a remarkable victory for the Indians, in which the attacking troops were essentially wiped out. Black Elk reported that he did not regret participating in the battle "because the Indians were in their own land, doing no harm, and were attacked without provocation." The Indians danced and sang all night.

Post-battle

Though the battle had been won, the war had not. The hard winter came early. The Indians seemed to be trailed by white soldiers. Some encampments were attacked and the Indians killed in their sleep. Indian removal began, though many chose death over assimilation or imprisonment on reservations. Over the next year, the new forces relentlessly pursued the Lakota, forcing many of the Indians to surrender. Sitting Bull refused to surrender and in May 1877, led his band across the border into Canada, where he remained in exile for many years, refusing a pardon and the chance to return.

In that same month, Crazy Horse surrendered to U.S. troops at Camp Robinson in Nebraska. Knowing that his people were weakened by cold and hunger, he believed there was no recourse. He and his people resided near the Red Cloud Agency for the next four months. He fled to the nearby Spotted Tail Agency with his ill wife in September. After meeting with military officials at the adjacent military post of Camp Sheridan, he agreed to return to Camp Robinson. Upon his return, Crazy Horse was arrested and murdered during the night; some accounts say he was attempting to escape at the time.

Using his visions

When Black Elk was about 15 years old, his family moved to Canada to join Sitting Bull. At this time, he began receiving and using visions to remove his people from impending danger. The voices of his spirit guides also led them to bison and other animals for food.

By the time he was 16, Black Elk began to feel uneasy. He had received a great vision years earlier and shared it with no one. Though his spirit guides continued to assist him and his people in their daily lives, he began to fear the time that they might soon confront him, demanding to know why he had done nothing with his vision.

Finally, at the age of 17, Black Elk shared his vision with the medicine man, Black Road. Black Road advised him that he must perform the duty he was given in his vision. He instructed him to first hold a horse dance. With the re-enactment of his vision through the ritual as guided by Black Road and assisted by his parents, Black Elk was then considered one of the medicine men.

At the age of 18, Black Elk began to feel that he should join the Oglala, and perform the duty his vision entrusted to him. This was a difficult period of time for him, as he lamented the suffering of his people as they were forcefully relocated again and again as their allotted lands were shrunk by the government. He had been able to help individuals, but not his tribe as a whole. Black Elk moved to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Performing a lamentation ritual, he received confirmation of his earliest vision, with the mandate to help his people.

At the age of 19, Black Elk began healing the sick. At this time, he began to share more in detail the aspects of his vision. He understood that he could not be empowered to fulfill each aspect until he revealed it to another and acted it out.

Adulthood

By the time Black Elk was 20 years old, his people were suffering greatly. They were dying of starvation and disease. Forced onto reservations, they could not practice their traditional ways of life.

Traveling

At this time, Black Elk heard that Buffalo Bill Cody was hiring Indians to use in his Wild West Show. He decided to join, thinking that it might afford him the opportunity to learn some of the white man's "magic." Traveling to the big cities of Chicago, Omaha, and New York depressed Black Elk. The way of life without relationship to nature convinced him that the whites were actually lacking in knowledge and had no secrets to share.

Buffalo Bill took his show to England, where they had an audience with Queen Victoria. From London, Black Elk went to the city of Manchester. Buffalo Bill returned to the U.S. without him. With other Sioux who remained, he worked in another western show (Mexican Joe’s) which traveled to Germany, Italy, and Paris. While in Paris, he became involved with a girl. Becoming homesick and ill, the girl's family took him in and nursed him back to health. During this illness, he had a vision of his home, riding on a cloud over the Black Hills and the Pine Ridge Reservation. Awakening from his vision, he was informed that he had been near death for three days. He returned to America soon after that.

The Ghost Dance

Upon Black Elk's return home, he discovered that both his sister and his brother had died in his absence. His father died soon after. Though he lacked power when he had left his homeland, it came back to him upon his return.

He soon heard rumors of a man among the Paiutes, Wovoka, who taught of ways to save the Native Americans, bring back the buffalo, and rid their lands of the white man. Three Oglala men went to investigate and returned with news of the Ghost Dance. The Ghost Dance soon spread from Wovoka's home in Nevada throughout all lands west of the Mississippi River, though it was adapted tribe by tribe.

A dance was held at Wounded Knee Creek, which Black Elk witnessed. There were similarities to his vision, such as the circle dance and the flowering stick. He believed perhaps Wovoka had received a similar vision to his. Black Elk began to join in the dances, during which he experienced visions similar to his first vision. After this, he began to make holy shirts, which he believed would protect the lives of those who wore them.

Soon, however, Black Elk received a vision while dancing, which he interpreted as a sign that he had made a mistake in forsaking his great vision for the lesser ones he had received while ghost dancing. Government agents began to crack down on the Ghost Dance, and warned Black Elk's encampment. Fearing arrest, they moved to a Brule encampment on Wounded Knee Creek.

Massacre at Wounded Knee

While there, they received news of Sitting Bull's death, which came during an attempted arrest. Soon the Minneconjou Chief Big Foot arrived at their encampment, suffering from pneumonia, with 400 people who had escaped to the Badlands when Sitting Bull was killed. Starving and freezing, they surrendered to soldiers who brought them to Wounded Knee.

The presence at Wounded Knee of the highly respected Chief Big Foot scared the soldiers, who feared an uprising. The cavalry had received orders to disarm the Natives before sending the "more troublesome" ones to Omaha via train. During the attempt to disarm, a scuffle ensued. Though the details are not clearly known, shots were fired and a battle began. Having largely given up their weapons, the Indians, including many women and children, sought shelter in a ravine. They were killed while fleeing and seeking shelter.

Hearing the shots, Black Elk, accompanied by about 20 others, rode toward them. Witnessing the massacre, they rode into the fight. It was over, and men, women, and children lie dead or dying in the snow. A blizzard the following day covered their bodies, freezing them into grotesque shapes.

The following day Black Elk went out with a Lakota war party. He was wounded, but determined to continue the fight, until an older warrior convinced him to live and help his people.

End of the dream

The month following the massacre at Wounded Knee, in January 1891, Black Elk joined an attack at Smoky Earth. Stealing the soldiers' horses, the warriors retreated into the Badlands. Chief Red Cloud, fearing the suffering that followed their victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, convinced them to surrender.

Black Elk felt this final surrender was the end of a dream, the end of his nation, and a sign that he had failed to live up to the command of his vision.

Later years

After the Wounded Knee Massacre and the Sioux's final surrender, Black Elk married and began to raise a family. He converted to Catholicism approximately ten years later and became a catechist. The reservation Indians were not allowed to meet in large groups and were forbidden to practice the native religion. However, as a catechist, Black Elk had the freedom to help his people with money, group gatherings, and prayer.

Unable to fulfill his vision, Black Elk opted to serve his people, though in a "white man's way." He lived this way for nearly 40 years. In 1930 he was interviewed by John Neihardt, an acclaimed American poet. Seeming to have expected his visit, connecting with him in a special way, he entrusted him to share his story. Though they needed an interpreter (Black Elk never learned to speak English), a bond of trust was formed. After sharing his life story over a period of several interview sessions, Neihardt and Black Elk‚ÄĒdressed traditionally for the first time in decades‚ÄĒascended the 7,242 foot Harney Peak in the Black Hills, where he offered a prayer to Wakan Tanka for his people.

For the following twenty years, Black Elk remained a devout Catholic, walking to church every Sunday even when he was dying of tuberculosis. He raised a large family, with descendants living on his property on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

He passed from this life in August 1950.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- CliffsNotes by Wiley Publishing, Inc. Black Elk Speaks by John Gneisenau Niehardt. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- Reuben, Paul P. Black Elk (1863-1950); also known as Hehaka Sapa and Nicholas Black Elk. Perspectives in American Literature. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- Sanchez, Mark. Black Elk Speaks. Colorado State Education. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

Further reading

- Black Elk's As Told To books

- Black Elk, and John Gneisenau Neihardt. 1988. Black Elk speaks being the life story of a holy man of the Oglala Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803283598

- Neihardt, John Gneisenau, Black Elk, and Raymond J. DeMallie. 1984. The Sixth Grandfather Black Elk's teachings given to John G. Neihardt. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803216645

- Black Elk, and Joseph Epes Brown. 1953. The sacred pipe; Black Elk's account of the seven rites of the Oglala Sioux. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Brown, Joseph Epes. 1982. The spiritual legacy of the American Indian. New York: Crossroad. ISBN 0824504895

- Books about Black Elk

- Petri, Hilda Neihardt. 1995. Black Elk and Flaming Rainbow personal memories of the Lakota holy man and John Neihardt. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803283768

- Steltenkamp, Michael F. 1993. Black Elk holy man of the Oglala. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806125411

- Costello, Damian. 2005. Black Elk colonialism and Lakota Catholicism. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books. ISBN 1570755809

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.