Wind tunnel

A wind tunnel is a research tool developed to assist with studying the effects of air moving over or around solid objects.

Ways that wind-speed and flow are measured in wind tunnels:

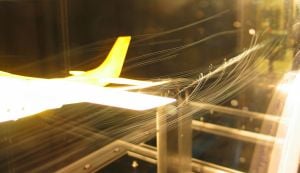

- Threads can be attached to the surface of study objects to detect flow direction and relative speed of air flow.

- Dye or smoke can be injected upstream into the air stream and the streamlines that dye particles follow photographed as the experiment proceeds.

- Pitot tube probes can be inserted in the air flow to measure static and dynamic air pressure.

History

English military engineer and mathematician Benjamin Robins (1707–1751) invented a whirling arm apparatus to determine drag and did some of the first experiments in aviation theory.

Sir George Cayley (1773-1857), the 'father of aerodynamics', also used a whirling arm to measure the drag and lift of various airfoils. His whirling arm was 5 feet long and attained top speeds between 10 and 20 feet per second. Armed with test data from the arm, Cayley built a small glider that is believed to have been the first successful heavier-than-air vehicle to carry a man in history.

However, the whirling arm does not produce a reliable flow of air impacting the test shape at a normal incidence. Centrifugal forces and the fact that the object is moving in its own wake mean that detailed examination of the airflow is difficult. Francis Herbert Wenham (1824-1908), a Council Member of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, addressed these issues by inventing, designing and operating the first enclosed wind tunnel in 1871.[1]

Once this breakthrough had been achieved, detailed technical data was rapidly extracted by the use of this tool. Wenham and his colleague Browning are credited with many fundamental discoveries, including the measurement of l/d ratios, and the revelation of the beneficial effects of a high aspect ratio.

Carl Rickard Nyberg used a wind tunnel when designing his Flugan from 1897 and onwards.

In a classic set of experiments, the Englishman Osborne Reynolds (1842-1912) of the University of Manchester demonstrated that the airflow pattern over a scale model would be the same for the full-scale vehicle if a certain flow parameter were the same in both cases. This factor, now known as the Reynolds Number, is a basic parameter in the description of all fluid-flow situations, including the shapes of flow patterns, the ease of heat transfer, and the onset of turbulence. This comprises the central scientific justification for the use of models in wind tunnels to simulate real-life phenomena.

The Wright brothers' use of a simple wind tunnel in 1901 to study the effects of airflow over various shapes while developing their Wright Flyer was in some ways revolutionary. It can be seen from the above, however, that they were simply using the accepted technology of the day, though this was not yet a common technology in America.

Subsequent use of wind tunnels proliferated as the science of aerodynamics and discipline of aeronautical engineering were established and air travel and power were developed.

Wind tunnels were often limited in the volume and speed of airflow which could be delivered.

The wind tunnel used by German scientists at Peenemünde prior to and during WWII is an interesting example of the difficulties associated with extending the useful range of large wind tunnels. It used some large natural caves which were increased in size by excavation and then sealed to store large volumes of air which could then be routed through the wind tunnels. This innovative approach allowed lab research in high speed regimes and greatly accelerated the rate of advance of Germany's aeronautical engineering efforts.

Later research into airflows near or above the speed of sound used a related approach. Metal pressure chambers were used to store high pressure air which was then accelerated through a nozzle designed to provide supersonic flow. The observation or instrumentation chamber was then placed at the proper location in the throat or nozzle for the desired airspeed.

For limited applications, Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) can augment or possibly replace the use of wind tunnels. For example, the experimental rocket plane SpaceShipOne was designed without any use of wind tunnels. However, on one test, flight threads were attached to the surface of the wings, performing a wind tunnel type of test during an actual flight in order to refine the computational model. It should be noted that, for situations where external turbulent flow is present, CFD is not practical due to limitations in present day computing resources. For example, an area that is still much too complex for the use of CFD is determining the effects of flow on and around structures, bridges, terrain, etc.

The most effective way to simulative external turbulent flow is through the use of a boundary layer wind tunnel.

There are many applications for boundary layer wind tunnel modeling. For example, understanding the impact of wind on high-rise buildings, factories, bridges, etc. can help building designers construct a structure that stands up to wind effects in the most efficient manner possible. Another significant application for boundary layer wind tunnel modeling is for understanding exhaust gas dispersion patterns for hospitals, laboratories, and other emitting sources. Other examples of boundary layer wind tunnel applications are assessments of pedestrian comfort and snow drifting. Wind tunnel modeling is accepted as a method for aiding in Green building design. For instance, the use of boundary layer wind tunnel modeling can be used as a credit for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification through the U.S. Green Building Council.

Wind tunnel tests in a boundary layer wind tunnel allow for the natural drag of the earth's surface to be simulated. For accuracy, it is important to simulate the mean wind speed profile and turbulence effects within the atmospheric boundary layer. Most codes and standards recognize that wind tunnel testing can produce reliable information for designers, especially when their projects are in complex terrain or on exposed sites.

How it works

Air is blown or sucked through a duct equipped with a viewing port and instrumentation where models or geometrical shapes are mounted for study. Typically the air is moved through the tunnel using a series of fans. For very large wind tunnels several meters in diameter, a single large fan is not practical, and so instead an array of multiple fans are used in parallel to provide sufficient airflow. Due to the sheer volume and speed of air movement required, the fans may be powered by stationary turbofan engines rather than electric motors.

The airflow created by the fans that is entering the tunnel is itself highly turbulent due to the fan blade motion, and so is not directly useful for accurate measurements. The air moving through the tunnel needs to be relatively turbulence-free and laminar. To correct this problem, a series of closely-spaced vertical and horizontal air vanes are used to smooth out the turbulent airflow before reaching the subject of the testing.

Due to the effects of viscosity, the cross-section of a wind tunnel is typically circular rather than square, because there will be greater flow constriction in the corners of a square tunnel that can make the flow turbulent. A circular tunnel provides a much smoother flow.

The inside facing of the tunnel is typically very smooth to reduce surface drag and turbulence that could impact the accuracy of the testing. Even smooth walls induce some drag into the airflow, and so the object being tested is usually kept near the center of the tunnel, with an empty buffer zone between the object and the tunnel walls.

Lighting is usually recessed into the circular walls of the tunnel and shines in through windows. If the light were mounted on the inside surface of the tunnel in a conventional manner, the light bulb would generate turbulence as the air blows around it. Simarly, observation is usually done through transparent portholes into the tunnel. Rather than simply being flat discs, these lighting and observation windows may be curved to match the cross-section of the tunnel and further reduce turbulence around the window.

Various techniques are used to study the actual airflow around the geometry and compare it with theoretical results, which must also take into account the Reynolds number and Mach number for the regime of operation.