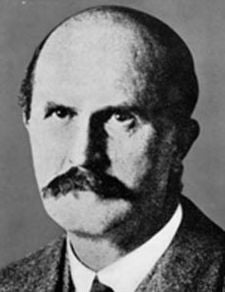

William Henry Bragg

|

William Henry Bragg | |

|---|---|

William Henry Bragg | |

| Born |

2 July 1862 |

| Died | 12 March 1942 |

| Residence | |

| Nationality | |

| Institutions | University of Adelaide University of Leeds University College London |

| Alma mater | Cambridge University |

| Academic advisor | J.J. Thompson |

| Notable students | W. L. Bragg Kathleen Lonsdale William Thomas Astbury |

| Known for | X-ray diffraction |

| Notable prizes | |

| Note that he is the father of William Lawrence Bragg. There was no PhD in Cambridge until 1919, and J.J. Thompson was in fact his Master's advisor. | |

Sir William Henry Bragg KBE, OM, MA (Cantab), PhD, (2 July 1862 – 10 March 1942) was an English physicist and chemist who shared the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics with his son Sir William Lawrence Bragg.

Early life

Bragg was the eldest child of Robert John Bragg, a sea captain who had become a farmer after receiving an inheritance, and his wife Mary Wood, daughter of a clergyman. Bragg was born at Westward near Wigton, Cumberland. Bragg's mother died in 1869, and Bragg was taken in and educated by his father's brothers. He later attended King William's College, Isle of Man, where he took an interest in sports and a variety of extracurricular activities on campus besides his formal studies. He won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, entered Trinity in 1881, and graduated in 1884 as third wrangler in the mathematical tripos.

University of Adelaide

Upon the implicit recommendation of J.J. Thompson, who was one of his instructors, Bragg won an appointment as the "Elder Professor of Pure and Applied Mathematics, who shall also give instruction in Physics"[1] at the University of Adelaide in Australia and began his duties there early in 1886. He then had what he considered a limited knowledge of physics, but there were only about a hundred students doing full courses at Adelaide of whom scarcely more than a handful belonged to the science school. Bragg was thus enabled to develop his knowledge of the subject in his early years. Bragg married Gwendolyn Todd, the daughter of Charles Todd, an astronomer and friend of Bragg's. In 1890, a son, William Lawrence Bragg, was born, and another, Robert, soon after. While Bragg's intense teaching schedule prevented him from conducting research, he retained a keen interest in the developments of physics, and read periodicals and papers.

X-rays

In 1896, only a year after William Roentgen discovered x-rays, Bragg rigged up an x-ray machine of his own to examine his son's broken elbow. This event is said to have been the first use of x-rays as a diagnostic tool in Australia. Bragg then conducted a series of well-attended lectures on x-rays, and established the first wireless telegraphy system in Australia in 1897. and That same year, he took a two-year sabbatical, spending the time visiting relatives in England and touring the continent and northern Africa with his family. In 1803, Bragg assumed the presidency of the Australian Association for the Advancement of Science. At the organization's annual meeting in 1904, convened in New Zealand, Bragg delivered an address on "Some Recent Advances in the Theory of the Ionization of Gases." This paper was the origin of his first book Studies in Radioactivity, published in 1912. Shortly after the delivery of his 1904 address some radium bromide was placed at the disposal of Bragg with which he was able to experiment.

Alpha rays

In December 1904 a paper by him "On the Absorption of a Rays and on the Classification of the a Rays from Radium" appeared in the Philosophical Magazine, and in the same number a paper "On the Ionization Curves of Radium," written in collaboration with Richard Kleeman, also appeared. these papers established that there were several types of alpha particles, that their absorption by a material increased with the atomic weight of the material, and that absorption dropped off steeply at a particular distance rather than exponentially as in the electron. These papers earned him an international reputation and won him membership in the Royal Society of London in 1907, among his sponsors being J.J. Thomson, Ernest Rutherford, and C.T.R. Wilson. Also in this year, Bragg's wife gave birth to their third child, Gwendolen. At the end of 1908 Bragg resigned his professorship at Adelaide to assume the Cavendish Chair of Physics at Leeds university. During his 23 years in Australia he had seen the number of students at Adelaide university nearly quadrupled, and had had a full share in the development of its excellent science school.

University of Leeds

Around this time, Bragg argued on behalf of the particle nature of X-rays. Bragg argued that X-rays retain their momentum far more than one would expect for electromagnetic waves, which spread out and weaken with distance. He later accepted evidence, supplied experimentally by Max von Laue and based on the detection of interference patterns made by X-rays passing through crystals, that x-rays are electromagnetic waves. But in a prophetic remark that would only be borne out 15 years later with the formulation of quantum mechanics, Bragg said that the problem was "not to decide between two theories of X-rays (wave or corpuscular), but to find, as I have said elsewhere, one theory which possesses the capacity of both." <<<Gonzalo and Lopez, 2003, 15>>>

Bragg's son, William Lawrence Bragg, was able to explain the patterns that X-rays make when they pass through a crystal. Bragg himself found a way to generate X-rays of a single wavelength, and invented the X-ray spectrometer. He was joined by his son at Leeds for a time, where they went on to establish the new science of X-ray analysis of crystal structure. Through X-ray analysis, they confirmed the earlier findings of Van 't Hoff on the spacial distribution of the bonds of the carbon atom through their analysis of the crystal structure of diamond. In 1915 father and son were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for independent and joint contributions to the analysis of the atomic structure of crystals, using the X-ray spectrometer and theoretical investigation. Their volume, X-Rays and Crystal Structure, went through five editions in ten years.

University College London

Bragg was appointed Quain professor of physics at University College London in 1915 but did not take up his duties there until after World War I. He did much work for the government at this time, largely connected with submarine detection through the improvement of the hydrophone, at Aberdour on Forth and at Harwich, and returned to London in 1918 as consultant to the admiralty. While Quain professor at London he continued his work on crystal analysis.

Royal Institution

From 1923 he was Fullerian professor of chemistry at the Royal ution and director of the Davy Faraday Research Laboratory. Bragg quickly gathered around him a group of competent researchers who later made important contributions to the field of X-ray crystallograpy. He also purchased a country home where members of the staff could socialize informally on weekends. The laboratory was practically rebuilt in 1929-30 and under Bragg's directorship many valuable papers were issued from the laboratory, mostly dealing with the investigation of organic compounds using X-ray diffraction methods.

Bragg instituted a series of popular lectures for young people, and infused his talks with simple yet profound reflections on the state of science in his time. In the 1930s, Bragg continued to be involved in research, and in his last years, from 1939 to 1942, wrote a series of papers to explain anomalies in the X-ray analysis of crystals, attributing them to imperfections in the crystal structure. One of these papers was published poshumously. Bragg died in 1942.

Legacy

Bragg was already an accomplished physicist with an established reputation before he and his son, William Lawrence, embarked on the investigations that would win them enduring fame and a Nobel prize. Bragg's success could have easily overwhelmed that of his son, but the two managed to work out their personal differences and work together productively.

Bragg did not conduct important research until he was in his 40s, in contrast to his son, whose independent accomplishments at the age of 22 made him the youngest Nobel prize winner. The work of the two demonstrates how there is no hard and fast rule to the manner in which scientists make an enduring contribution. Bragg's work and that of his son paved the way for deciphering the structure of complex organic molecules, leading to the unravelling of the structure of the DNA molecule in the early 1950s.

Bragg became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1907, was elected a vice-president in 1920, and served as president of the society from 1935 to 1940.

The lecture theatre of King William's College is named in his memory.

Since 1992 the Australian Institute of Physics has awarded the Bragg Gold Medal for Excellence in Physics for the best PhD thesis by a student at an Australian university.

In 1889, he married Gwendoline Todd, daughter of Sir Charles Todd, who died in 1929. He was survived by a daughter and his son, Sir William Lawrence Bragg, another son, Robert, died at Gallipoli[1]. Bragg was created C.B.E. in 1917, K.B.E. in 1920, and in 1931 was given the Order of Merit.

Timeline

- University of Adelaide (1886-1908)

- University of Leeds (1909-15)

- University College London (1915-23)

- Royal Institution

Prizes

- Nobel Prize (1915)

- Matteucci Medal (1915)

- Rumford Medal (1916)

- Copley Medal (1930)

- Hughes Medal (1931)

Selected publications

- William Henry Bragg, The World of Sound (1920)

- William Henry Bragg, The Crystalline State - The Romanes Lecture for 1925. Oxford, 1925.

- William Henry Bragg, Concerning the Nature of Things (1925)

- William Henry Bragg, Old Trades and New Knowledge (1926)

- William Henry Bragg, An Introduction to Crystal Analysis (1928)

- William Henry Bragg, The Universe of Light (1933)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hugh Anderson (1979). 'Bragg, Sir William Henry (1862 - 1942). Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 7 pp. pp 387-388. MUP. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gonzalo, Julio A., and Carmen Aragó López. 2003. Great solid state physicists of the 20th century. River Edge, N.J.: World Scientific. ISBN: 9812383360.

- Hunter, Graeme K. 2004. Light is a messenger: the life and science of William Lawrence Bragg. New York: Oxford. University Press. ISBN: 019852921X.

- Hunter, Graeme K. 2000. Vital forces: the discovery of the molecular basis of life. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN: 012361810X.

- Serle, Percival. 1949. "Bragg, Sir William Henry (1862-1942)," in Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- This article incorporates text from the 1949 edition of Dictionary of Australian Biography from Project Gutenberg of Australia, which is in the public domain in Australia and the United States of America.

| Honorary Titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Sir Frederick Hopkins |

President of the Royal Society 1935–1940 |

Succeeded by: Sir Henry Dale |

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.