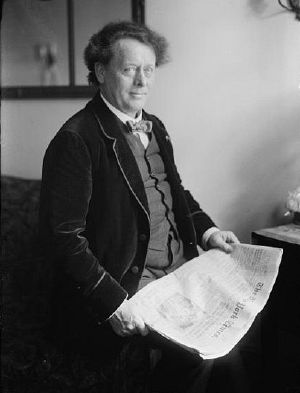

Willem Mengelberg

| Willem Mengelberg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Joseph Willem Mengelberg |

| Born | 28 March 1871 |

| Died | 21 March 1951 (aged 79) Zuort, Sent, Switzerland |

| Genre(s) | Classical |

| Occupation(s) | Composer,conductor, pedagogue |

| Years active | ca. 1890-1945 |

| Associated acts | Concertgebouw London Symphony New York Philharmonic |

Joseph Willem Mengelberg (28 March 1871 – 21 March 1951) was a Dutch conductor.

Biography

Mengelberg was born fourth of sixteen children to German born parents in Utrecht, Netherlands. He studied in the Cologne conservatory, including piano and composition. He was chosen as General Music Director of the city of Lucerne Switzerland at age 21.[1] where he was conductor of an orchestra and a choir, directed a music school, taught piano lessons and continued to compose.

Mengelberg is highly renowned for his work as the principal conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra from 1895 to 1945. In addition, Mengelberg founded the long-standing Mahler tradition of Concertgebouw. In 1902 he met Gustav Mahler and became friends with him. Mengelberg was instrumental in introducing most of Mahler's work to The Netherlands, and Mahler regularly visited The Netherlands to introduce his work to Dutch audiences. In fact, he edited some of his symphonies while in the Netherlands, making them sound better for the acoustics of Concertgebouw. This is perhaps one reason that this concert hall and its orchestra is renowned for its Mahler tradition.

Nevertheless, Mengelberg's importance as a conductor was not only due to his Mahler interpretations. He was also, for example, an exceptionally gifted performer of Richard Strauss; and even today his recordings of Strauss's tone poem Ein Heldenleben, which had been dedicated to him and the Concertgebouw Orchestra, are widely regarded by critics as among the best—if not the very best—of this piece ever made.

One criticism of Mengelberg's influence over Dutch musical life, most clearly articulated by the composer Willem Pijper, was that Mengelberg did not particularly champion Dutch composers during his Concertgebouw tenure, especially after 1920.[2]

Mengelberg was music director of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra from 1922 to 1928. Beginning in January 1926, he shared the podium with Arturo Toscanini; Toscanini biographer Harvey Sachs has documented that Mengelberg and Toscanini clashed over interpretations of music and even rehearsal techniques, creating division among the musicians that eventually resulted in Mengelberg leaving the orchestra. However, the maestro did make a series of recordings with the Philharmonic for both the Victor Talking Machine Company and Brunswick Records, including a 1928 electrical recording of Richard Strauss' Ein Heldenleben that was later reissued on LP and CD. One of his first electrical recordings, for Victor, was a two-disc set devoted to A Victory Ball by Ernest Schelling.

The most controversial aspect of Mengelberg's biography centers around his actions and behavior during the years of the Nazi occupation of Holland between 1940 and 1945. Some newspaper articles of the time gave the appearance that he acquiesced to the presence of the Nazi's ideological restrictions on particular composers. Explanations have ranged from political naiveté in general, to a general "blind spot" of criticism of anything German, given his own ancestry. Because of Mengelberg's co-operation with the occupying regime in The Netherlands during World War II, he was banned from conducting in the country by the Dutch government after the war in 1945. He was stripped of his honours and his passport. The original judgment was that Mengelberg would be banned from conducting in the Netherlands for the remainder of his life. Appeals by his attorneys led to a reduction in the sentence to a banning of six years from conducting, retroactively applied to start from 1945. This notwithstanding, he continued to draw a pension from the orchestra until 1949 when cut off by the city council of Amsterdam.[3] Mengelberg retreated in exile to Zuort, Sent, Switzerland, where he remained until his death in 1951, just two months before the expiration of his exile order.

Willem Mengelberg was the uncle of the musicologist and composer Rudolf Mengelberg and of the conductor, composer and critic Karel Mengelberg, who was himself the father of the prominent improvising pianist and composer Misha Mengelberg.

Recorded Legacy

In addition to his acclaimed recordings of Richard Strauss' Ein Heldenleben, Mengelberg left valuable discs of symphonies by Beethoven and Brahms, not to mention a wildly controversial but gripping reading of Bach's St. Matthew Passion.

His most characteristic performances are marked by a tremendous expressiveness and freedom of tempo, perhaps most remarkable in his recording of Mahler's fourth Symphony but certainly present in the aforementioned St Matthew Passion and other performances as well. These qualities, shared (perhaps to a lesser extent) by only a handful of other conductors of the era of sound recording, such as Wilhelm Furtwängler and Leonard Bernstein, make much of his work unusually controversial among classical music listeners; recordings that more mainstream listeners consider unlistenable will be hailed by others as among the greatest recordings ever made.

Many of his recorded performances, including some live concerts in Amsterdam during World War II, have been reissued on LP and CD. While he was known for his recordings of the German repertoire, Capitol Records issued a powerful, nearly high fidelity recording of Cesar Franck's Symphony in D minor, recorded in the 1940s with the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Due to the Dutch government's six-year ban on Mengelberg's conducting activities, he made no more recordings after 1945. Some of his performances in Amsterdam were recorded on the innovative German tape recorder, the Magnetophon, resulting in unusually high fidelity for the time.

Sound films of Mengelberg conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra, during live concerts in Amsterdam, have survived. Among these are a 1931 performance of Karl Maria von Weber's Oberon overture and a 1939 performance of Bach's St. Matthew Passion.[4]

Notes

- ↑ Kalisch, Alfred (1 July 1912). Willem Mengelberg. The Musical Times vol. 53 (no. 833): pp. 433–435.

- ↑ Hoogerwerf, Frank W. (July 1976). Willem Pijper as Dutch Nationalist. The Musical Quarterly vol. 62 (no. 3): pp. 358–373.

- ↑ "I Bow Humbly", Time, 28 February 1949. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ↑ Willem MENGELBERG, Bach's St. MATTHEW/Matthäus Passion and The Philips Miller Optical Recording System

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

- Willem Mengelberg at the Bach Cantatas Website

- Listen to Mengelberg conduct and read his biography

- Discography

- The recording of Bach's St. Matthew Passion

- [1]

Template:Concertgebouworkest conductors

| |||||

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.