Tudor Dynasty

| English Royalty |

|---|

| House of Tudor |

| Henry VII |

| Arthur, Prince of Wales |

| Margaret, Queen of Scots |

| Henry VIII |

| Elizabeth Tudor |

| Mary, Queen of France |

| Edmund, Duke of Somerset |

| Henry VIII |

| Henry, Duke of Cornwall |

| Mary I |

| Elizabeth I |

| Edward VI |

| Edward VI |

| Mary I |

| Elizabeth I |

The Tudor dynasty or House of Tudor' (Welsh: Tudur) was a series of five monarchs of Welsh origin who ruled England and Ireland from 1485 until 1603. The three main monarchs (Henry VII, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I) each played an important part in turning England from a European backwater still immersed in the Middle Ages into a powerful Renaissance state that in the coming centuries would dominate much of the world.

The kings and queens of this era ruled England from 1485 - 1603. During this reign, the Tudors created the Church of England and also strengthened the navy. Two of the monarchs that were in power during the Tudor Dynasty are some of the most famous English monarchs of all time. It began with Owen Tudor, who was a squire in Henry V's court. After Henry's death, Owen Tudor married his widow, Katherine of Valois, and had five children with her. Edmund, their eldest surviving son, married Margaret Beaufort, a descendant of John of Lancaster and at one point a potential heiress to Edmund's half-brother, Henry VI. Although Edmund died childless, his 13-year old widow bore a son several months after her husband's death. This child would become Henry VII.

Feudal Circumstances

While Tudors made much of their feudal title to Richmondshire, Middleham and its subsidiary Snape were Neville bases. Bedale Ricardian Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell resisted Henry VII. Robert Aske, of the family of Aske Hall in Richmond took complaints to Henry VIII in the Pilgrimage of Grace, objecting to the King's "casting off" of Queen Catherine of Aragon and his daughter Princess Mary. Simon Digby resisted Elizabeth I, even though Digby's family were installed in the region by Henry VII as a replacement for Lovell. Sir George Bowes complained in defence of Digby's son's innocence, saying further that the rebels had not been able to be quelled by Lord Latimer. This Rising of the North for Charles Neville of Westmorland resulted in another installment of a dignitary puppet over Bedale by the Queen Elizabeth—Ambrose, Earl of Warwick.

Although dynastically Lancastrian, the Tudors were politically Yorkist. In this sense, they were dual like the Nevilles (dynastically Yorkist, politically Lancastrian) and which was the point of union between both houses, supposedly resolving the Wars of the Roses. The Tudors superseded this Neville crossover precedent, effectively balancing rival factions, as the Rising of the North itself ended the Percy-Neville feud. The Tudor dynasty and its unification of Richmondshire (like Wales, or Brittany to France) into the body politic of the English Royal Domain, thus contributed to the future Stuart succession by dominating foreign influences (e.g. the Castilian intrigue formed by John of Gaunt and pursued by Henry VII). The border country had become the pivot upon which the monarchy was secured, by subordination of the "Middle Shires"—as they came to be known under King James I.

This consolidation of power under the Star Chamber Court and its reliance upon the subordination of palatine agricultural districts (e.g. Council of Wales, Council of the North, etc.) was to resemble the original Lancastrian high court party of Henry VI, instigating once again a Low Country (Burgundian Flanders) mercantile and Estuary opposition in the heirs of Mary Tudor, Duchess of Suffolk and their Dudley allies (carrying the notorious Warwick title). These economic and dynastic alliances of the Yorkists would re-emerge in the wake of the beheading of the last Plantagenet, Margaret Pole, 8th Countess of Salisbury. Religion became intertwined with politics with the declaration of cuius regio, eius religio. This meant that English society had become divisive once more; even more so than before. Future Stuart succession would attempt to align the high court party with the high church party, in the same manner as the Spanish Habsburg standard.

Jealous heirs to the Yorkists would challenge the stratifying intentions of these Lancastrian heirs, championing "the underdog"—themselves and the mercantile, industrial classes. Feudal structure in which a monarch was held in check by peers of the realm was challenged by nationalism under the monarchy; the Tudors having broken bastard feudalism upon the support of civil servants who demanded compensation. In the traditions of Simon de Montfort and Richard of York, Parliament became the vehicle for upward mobility by those dispossessed by the Crown. These officers of state decided to do their own kingmaking when the opportunity presented itself, but choosing the rival faction established under the Burgundian and ultimately German alliances of the Hundred Years' War (against the French peace of Margaret of Anjou).

Marital Policies

Owen and Edmund married Lancastrians, but Henry VII and Henry VIII, including Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset wed Yorkists.

The first marriage of Henry VIII was Lancastrian and to Catherine of Aragon, strategically poised to court Catholic (specifically, Spanish and Imperial) powers, a policy seen again in Mary's marriage to Philip II of Spain.

The second (foreign) marriage of Henry VIII was Yorkist and to Anne of Cleves, strategically poised to court Protestant German powers.

Tudor marital policy thus reflected the wish for "via media" as pursued in religious affairs, which was in some ways a continuation of the need to balance the Lancastrian and Yorkist camps.

The sisters of Henry were wed to the Auld Alliance dynasties of Scotland and France, but only the Scottish alliance was considered fruitful, with the French alliance lost to Suffolk. In each sense, the Tudor dynasty sought peace and partnership with the dignified Catholic powers.

In the very distant future, this was an ideal seized upon by the (Germanic) dynasty of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, which shored up respect for their position by adopting the native House of Windsor. In that case, it was a replication of the old (Romance) Angevin change to Plantagenet during the reign of Henry III. Writers and propagandists often align the Anglo-Saxon dynasty with Germanic culture and the Norman dynasty with Romance culture, but comment little on the common Celtic British heritage (e.g. like the Tudors' own putative descent from Brutus of Troy) tying them together as one populace.

The Tudor Period

The Tudor historical period usually refers to the period 1485 – 1558, especially in relation to the History of England. This coincides with the rule of the Tudor dynasty in England, with the exception of Elizabeth I. Occasionally the term is used more broadly to capture Elizabeth's reign as well, though in general 1558 – 1603 is treated separately as the Elizabethan era.

Monarchs of England

The five Tudor monarchs were:

- King Henry VII (1485-1509)

- King Henry VIII (1509-1547); son of Henry VII

- King Edward VI (1547-1553); son of Henry VIII

- Queen Mary I (1553-1558); eldest daughter of Henry VIII

- Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603); second daughter of Henry VIII

Henry VII's great-granddaughter, Lady Jane Grey also served as Queen for nine days before being deposed by Mary I. Jane was later executed along with her husband Guildford Dudley, son of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland. This was a prelude to the Puritan usurpations of the Stuart era, as the Dudleys were invested in the Pilgrims' American colonisation.

To the Tudor period belongs the elevation of the English-ruled state in Ireland from a Lordship to a Kingdom (1541).

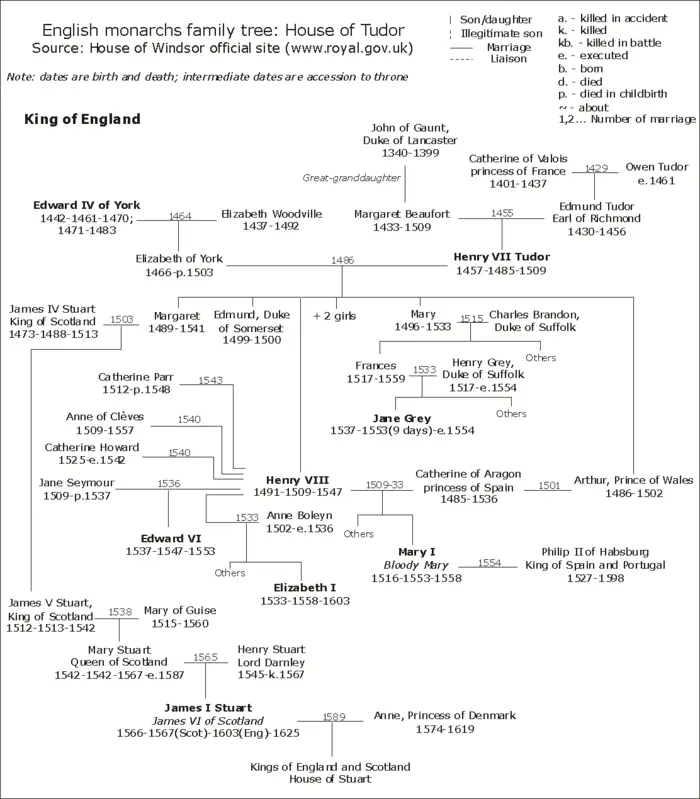

Tudor Family Tree

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anglo, Sydney. Spectacle, pageantry, and early Tudor policy. Oxford: Clarendon P. 1969. ISBN 9780198223085

- Guy, J. A. The Tudor monarchy. Arnold readers in history. London: Arnold 1997. ISBN 9780340652190

- Plowden, Alison. The House of Tudor. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Pub. 1998. ISBN 9780750918909

- Turton, Godfrey Edmund. The dragon's breed: the story of the Tudors from earliest times to 1603. London: P. Davies 1970. ISBN 9780432165300

External links

- Tudor Place Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- Tudor History Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- House of Tudor Chronology Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- Official British Royal Site Discussion on the Tudors Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- Tudor and Stuart Family Tree from Official British Royal Site Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- Tudor History Retrieved July 7, 2007.

| House of Tudor | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: House of York |

Ruling House of the Kingdom of England 1485 – 1603 |

Succeeded by: House of Stuart |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.