Theodora (sixth century)

Theodora (c. 500–June 28 548) was empress of the Byzantine Empire and the wife of Emperor Justinian I. Along with her husband, she is a saint in the Orthodox Church, commemorated on November 14.

Early Life

Theodora was born into the lowest class of Byzantine society, the daughter of Acacius, a bear keeper for the circus. Much of the information from this earliest part of her life comes from the Secret History of Procopius, published posthumously. Critics of Procopius (whose work reveals a man seriously disillusioned regarding his rulers) have dismissed his work as vitriolic and pornographic, but have been unable to discredit his facts. For example, the sources do not dispute Theodora emerged as a comic actress in burlesque theater, and that her talents tended toward what we might call low physical comedy. While her advancement in Byzantine society was up and down, she made use of every opportunity. She had admirers by the score. Procopius writes that she was a courtesan and briefly served as the mistress of Hecebolus, the governor of Pentapolis, by whom she bore her only child, a son. There was a downside to her repertoire as well; Procopius also repeatedly notes her lack of shame and cites a number of scenes to demonstrate it, and also the low regard in which she was held by respectable society.

It is believed by some scholars that sometime before meeting Justinian she became an adherent of the Non-Chalcedonian sect of Christianity, which claims Christ was of one incarnate nature, remaining their partisan throughout her life. Others instead argue that her association with Monophysitism is largely because of Justinian's putting her in charge of courting the Non-Chalcedonian reunion with the Chalcedonian party in the Church, and so while remaining Chalcedonian herself, she was pastorally favorable toward the non-Chalcedonians.

In 523 Theodora married Justinian, the magister militum praesentalis in Constantinople. On his accession to the Roman Imperial throne in 527 as Justinian I, he made her joint ruler of the empire, and appears to have regarded her as a full partner in their rulership. This proved to be a wise decision. A strong-willed woman, she showed a notable talent for governance. In the Nika riots of 532, her advice and leadership for a strong (and militant) response caused the riot to be quelled and probably saved the empire. A contemporary official, Joannes Laurentius Lydus, remarked that she was "superior in intelligence to any man"[1].

Some scholars believe that Theodora was Byzantium's first noted proponent—and, according to Procopius, practitioner—of abortion; she convinced Justinian to change the law that forbade noblemen to marry lower class women (like herself). Theodora also advocated the rights of married women to commit adultery, and the rights of women to be socially serviced, helping to advance protections and delights for them; and was also something of a voice for prostitutes and the downtrodden. She also helped to mitigate the breach in Christian sects that loomed large over her time; she probably had a large part in Justinian's efforts to reconcile the Non-Chalcedonians to the Chalcedonian party.

Other scholars (and those who venerate Theodora as a saint) instead regard Theodora's achievements for women not as a modern feminist "liberation" to commit abortion or adultery but rather as a truly egalitarian drive to give women the same legal rights as men, such as establishing homes for prostitutes, passing laws prohibiting forced prostitution, granting women more rights in divorce cases, allowing women to own and inherit property, and enacting the death penalty for rape, all of which raised women's status far above that current in the Western portion of the Empire.

There were less charitable acts as well. Rumors spoke of private dungeons in her quarters into which people she disapproved of disappeared forever, though such rumors can be found regarding nearly any royal figure. More congenial is the story of how she sheltered a deposed patriarch for 12 years without anyone knowing of it.

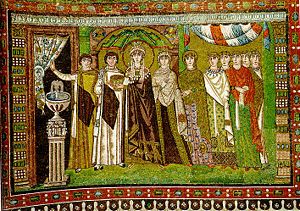

Theodora died of an unspecified cancer before the age of 50, some 20 years before Justinian died. It should be noted that there is no documentation to suggest that she died of breast cancer as some scholars have suggested. Her body was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles, one of the splendid churches the emperor and empress had built in Constantinople. Both Theodora and Justinian are represented in beautiful mosaics that exist to this day in the Basilica of San Vitale at Ravenna in northern Italy, which was completed a year before her death.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Graves, Robert. Count Belisarius. NY: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1982 ISBN 9780374517397 (A historical novel by the author of "I, Claudius" which features Theodora as a character. Original 1938)

- Gibbon, Edward. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. (NY: Modern Library, 1983 ISBN 9780394604022 See volume 4, chapter 40 for Gibbon's account of Theodora.) Online at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- Bury, J. B. History of the Later Roman Empire. NY: Dover, 1963 (Volume 2 deals with the reign of Justinian and Theodora)

- Procopius Secret History, translated by Richard Atwater, (Chicago: P. Covici, 1927; New York: Covici Friede, 1927), reprinted, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1961, online at Fordham University: the Internet Medieval Sourcebook Procopius The Secret History

External links

- Justinian, Theodora and Procopius Retrieved August 20, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Lynn Hunt et al., The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures, Boston Bedford, 2001, p. 263.