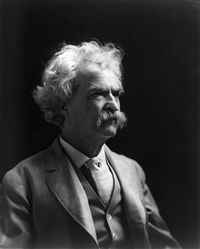

Samuel Clemens

| |

| Pseudonym(s): | Mark Twain |

|---|---|

| Born: | November 30, 1835 Florida, Missouri |

| Died: | April 21, 1910 Redding, Connecticut |

| Occupation(s): | Humorist, novelist, writer |

| Nationality: | American |

| Literary genre: | Historical fiction, non-fiction, satire |

| Magnum opus: | Adventures of Huckleberry Finn |

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30 1835 – April 21 1910), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American humorist, satirist, novelist, writer, and lecturer.

Although Twain was confounded by financial and business affairs, his humor and wit were keen, and he enjoyed immense public popularity. At his peak, he was probably the most popular American celebrity of his time. In 1907, crowds at the Jamestown Exposition thronged just to get a glimpse of him. He had dozens of famous friends, including William Dean Howells, Booker T. Washington, Nikola Tesla, Helen Keller, and Henry Huttleston Rogers. Fellow American author William Faulkner is credited with writing that Twain was "the first truly American writer, and all of us since are his heirs." Twain died in 1910 and is buried in Elmira, New York.

Pen names

Clemens maintained that his primary pen name, "Mark Twain," came from his years working on Mississippi riverboats, where two fathoms (12 ft, approximately 3.7 m) or "safe water" was measured on the sounding line. The riverboatman's cry was "mark twain" or, more fully, "by the mark twain" ("twain" is an archaic term for two). "By the mark twain" meant "according to the mark [on the line], [the depth is] two fathoms". Clemens provides a footnote to Chapter 8 ("Perplexing Lessons") of Life on the Mississippi where he explains "mark twain" as "two fathoms" and "Mark three is three fathoms".

Clemens claims that his famous pen name was not entirely his invention. In Chapter 50 of Life on the Mississippi he wrote:

Captain Isaiah Sellers was not of literary turn or capacity, but he used to jot down brief paragraphs of plain practical information about the river, and sign them "MARK TWAIN," and give them to the "New Orleans Picayune." They related to the stage and condition of the river, and were accurate and valuable; ... At the time that the telegraph brought the news of his death, I was on the Pacific coast. I was a fresh new journalist, and needed a nom de guerre; so I confiscated the ancient mariner's discarded one, and have done my best to make it remain what it was in his hands—a sign and symbol and warrant that whatever is found in its company may be gambled on as being the petrified truth; how I have succeeded, it would not be modest in me to say.[1]

Regardless of the source of the name, "Mark Twain," the alter ego of Samuel Clemens, was "born" in the office of the Nevada Territorial Enterprise, when the name first appeared on an article published on February 3, 1863.

Biography

Growing up

Mark Twain was born in Florida, Missouri, on November 30, 1835, to John Marshall Clemens and Jane Lampton Clemens.[2] When he was four, his family moved to Hannibal, a port town on the Mississippi River which later served as the inspiration for the fictional town of St. Petersburg in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Missouri had been admitted as a slave state in 1821 as part of the Missouri Compromise, and from an early age Twain was exposed to the institution of slavery, a theme which Twain was to later explore in his work. Ironically enough, Twain was in fact colorblind, which fueled his witty banter in the social circles of the day. In 1847, when Twain was eleven, his father fell ill with pneumonia and died that March. As a teenager Twain worked as an apprentice printer; when he was sixteen, he began writing humorous articles and newspaper sketches. When he was eighteen, he left Hannibal, working as a printer in New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. At the age of 22, Twain returned to Missouri and worked as a riverboat pilot and earned $250 which was a "pricely amount" back then, until trade was interrupted by the American Civil War in 1861.

Roughing it out west

Missouri, although a slave state and considered by many to be part of the South, declined to join the Confederacy and remained loyal to the Union. When the war began, Clemens and his friends formed a Confederate militia (an experience he depicted in his 1885 short story, "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed"), but he saw no military action and the militia disbanded after two weeks. His friends joined the Confederate Army; Clemens joined his brother, Orion, who had been appointed secretary to the territorial governor of Nevada, and headed west. They traveled for more than two weeks on a stagecoach across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains to the silver-mining town of Virginia City, Nevada. On the way, they visited the Mormon community in Salt Lake City. Clemens' experiences in the West contributed significantly to his formation as a writer, and became the basis of his second book, Roughing It.

Once in Nevada, Clemens became a miner, hoping to strike it rich discovering silver in the Comstock Lode. He stayed for long periods in camp with his fellow prospectors—another life experience that he later put to literary use. After failing as a miner, Clemens obtained work at a newspaper called the Daily Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City. It was there he first adopted the pen name "Mark Twain" on February 3, 1863 when he signed a humorous travel account with his new name.

Career overview

Twain's greatest contribution to American literature is generally considered to be his novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. As Ernest Hemingway once said:

- "All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn. ...all American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since."

Also popular are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court and the non-fiction book Life on the Mississippi.

Beginning as a writer of light, humorous verse, Twain evolved into a grim, almost profane chronicler of the vanities, hypocrisies and murderous acts of mankind. At mid-career, with Huckleberry Finn, he combined rich humor, sturdy narrative and social criticism in a way that is almost unrivaled in world literature.

Twain was a master at rendering colloquial speech, and helped to create and popularize a distinctive American literature built on American themes and language.

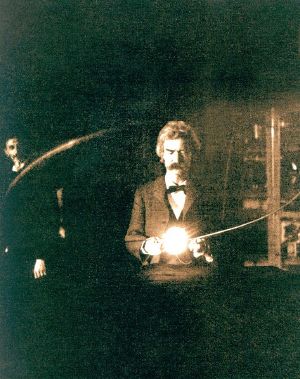

Twain also had a fascination with science and scientific inquiry. He developed a close and lasting friendship with Nikola Tesla, and the two spent quite a bit of time together (in Tesla's laboratory, among other places). Such fascination can be seen in Twain's book A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, which features a time traveler from the America of Twain's day, using his knowledge of science to introduce modern technology to Arthurian England. Twain also patented an improvement in adjustable and detachable straps for garments. Mark Twain was opposed to vivisection of any kind, not on a scientific basis, but rather an ethical one, in which he states that no sentient being should unconsentingly be made to suffer for another.

- "I am not interested to know whether vivisection produces results that are profitable to the human race or doesn't. ... The pain which it inficts upon unconsenting animal is the basis of my enmity toward it, and it is to me sufficient justification of the enmity without looking further."[3]

From 1901 until his death in 1910, Twain was vice president of the American Anti-Imperialist League.[4] The League opposed the annexation of the Philippines by the United States. Twain wrote Incident in the Philippines, posthumously published in 1924, in response to the Moro Crater Massacre, in which six hundred Moros were killed. Many but not all of Mark Twain's neglected and previously uncollected writings on anti-imperialism appeared for the first time in book form in 1992.

From the time of its publication there have been occasional attempts to ban Huckleberry Finn from various libraries because Twain's use of local color is offensive to some people. Although Twain was against racism and imperialism far ahead of the public sentiment of his time, those who have only superficial familiarity with his work have sometimes condemned it as racist because it accurately depicts language in common use in the 19th-century United States. Expressions that were used casually and unselfconsciously then are often perceived today as racist (today, such racial epithets are far more visible and condemned). Twain himself would probably be amused by these attempts; in 1885, when a library in Concord, Massachusetts banned the book, he wrote to his publisher, "They have expelled Huck from their library as 'trash suitable only for the slums'; that will sell 25,000 copies for us for sure."

Many of Mark Twain's works have been suppressed at times for various reasons. 1880 saw the publication of an anonymous slim volume entitled 1601: Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors. Twain was among those rumored to be the author, but the issue was not settled until 1906, when Twain acknowledged his literary paternity of this scatological masterpiece.

At least Twain saw 1601 published during his lifetime. During the Philippine-American War, Twain wrote an anti-war article entitled The War Prayer. Through this internal struggle, Twain expresses his opinions of the absurdity of slavery and the importance of following one's personal conscience before the laws of society. It was submitted to Harper's Bazaar for publication, but on March 22, 1905, the magazine rejected the story as "not quite suited to a woman's magazine." Eight days later, Twain wrote to his friend Dan Beard, to whom he had read the story, "I don't think the prayer will be published in my time. None but the dead are permitted to tell the truth." Because he had an exclusive contract with Harper & Brothers, Mark Twain could not publish The War Prayer elsewhere; it remained unpublished until 1923.

In later years, Twain's family suppressed some of his work which was especially irreverent toward conventional religion, notably Letters from the Earth, which was not published until 1962. The anti-religious The Mysterious Stranger was published in 1916, although there is some scholarly debate as to whether Twain actually wrote the most familiar version of this story. Twain was critical of organized religion and certain elements of the Christian religion through most of the end of his life, though he never renounced Presbyterianism [1].

Perhaps most controversial of all was Mark Twain's 1879 humorous talk at the Stomach Club in Paris, entitled Some Thoughts on the Science of Onanism, which concluded with the thought, "If you must gamble your lives sexually, don't play a lone hand too much." This talk was not published until 1943, and then only in a limited edition of fifty copies.

Financial matters

Although Twain made a substantial amount of money through his writing, he squandered much of it through bad investments, mostly through new inventions. These included the bed clamp for infants, a new type of steam engine that he had to sell for scrap, the kaolatype (a machine designed to engrave printing plates), the Paige typesetting machine (this investment was over $200,000 and while a technical marvel was too complex for wide commercial use), and finally, his publishing house that—while enjoying initial success by selling the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant—went bust soon after. Fortunately, Twain's writings and lectures enabled him to recover financially. [5]

Twain today

Visitors still pay homage to Mark Twain by visiting the places he lived. His birthplace is preserved in Florida, Missouri , and the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum in Hannibal, Missouri is one of the most popular museums because it provided the setting for much of Twain's work. Visitors can tour the Mark Twain Cave and ride a riverboat on the Mississippi River. In 1874 Twain built a family home in Hartford, Connecticut where he and Livy raised their three daughters. That home is preserved and open to visitors as the Mark Twain House. Twain lived in many homes in the U.S. and abroad.

Trivia

Template:Toomuchtrivia

- Twain was born and died in years in which Halley's Comet appeared (1835-1910).

- Twain had a mole above his right pectoral which he dubbed "Mr. Cantankerous".

- In 1906, his daughter Clara Clemens married the Jewish Russian emigre pianist and conductor Ossip Gabrilowitsch. Clara was a singer who appeared with her husband in recital. Twain and Gabrilowitsch share a gravestone in Elmira, N.Y.

- Mark Twain's wife, Olivia Langdon, was known as Livy to her family and friends.

- Livy's nickname for her husband was "Youth."

- Twain preferred cats over dogs and owned numerous cats throughout his lifetime.

- Twain was a member of the secret and powerful Bohemian Club

Epigrams

- "A habit cannot be thrown out the window, it must be coaxed down the stairs one step at a time." -Pudd'nhead Wilson's Calendar

- "A man is never more truthful than when he acknowledges himself a liar." -Mark Twain and I by Opie Read

- "Love your enemy, It'll scare the hell out of him"

- "'Classic.' A book which people praise and don't read." -Following the Equator, Pudd'nhead Wilson's New Calendar

- "Clothes make the man. Naked people have little or no influence on society." -More Maxims of Mark

- "I have been complimented many times and they always embarrass me; I always feel that they have not said enough." -Speech, September 23, 1907

- "India: Land of religions, cradle of human race, birthplace of human speech, grandmother of legend, great grandmother of tradition." [6]

- "The lack of money is the root of all evil." -More Maxims of Mark

- "It is by the goodness of God that in our country we have those three unspeakably precious things: freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, and the prudence never to practice either of them." -Following the Equator, Pudd'nhead Wilson's New Calendar

- "Jesus died to save men — a small thing for an immortal to do, & didn't save many, anyway; but if he had been damned for the race that would have been act of a size proper to a god, & would have saved the whole race. However, why should anybody want to save the human race, or damn it either? Does God want its society? Does Satan?" -Notebook #42

- "October: This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February." -Pudd'nhead Wilson's Calendar

- "Rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated." (The original quote was "The report of my death was an exaggeration"; cf. Ron Powers, Mark Twain: A Life, p. 585)

- The saying, "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics," is sometimes attributed to Twain. He did not coin the phrase, but he did popularize it in the United States.

- "To create man was a fine and original idea; but to add the sheep was a tautology." -(St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 30, 1902; cf. Ron Powers, Mark Twain: A Life, p. 611)

- "We all do no end of feeling, and we mistake it for thinking. And out of it we get an aggregation which we consider a boon. Its name is public opinion. It is held in reverence. Some think it the voice of God." (Corn-Pone Opinions)

- "When angry count to four, when very angry, swear." -Pudd'nhead Wilson's Calendar

- "When I, a thoughtful and unblessed Presbyterian, examine the Koran, I know that beyond any question every Mohammedan is insane, not in all things, but in religious matters. When a thoughtful and unblessed Mohammedan examines the Westminster Catechism, he knows that beyond any question I am spiritually insane. I cannot prove to him that he is insane, because you never can prove anything to a lunatic—for that is a part of his insanity and the evidence of it. He cannot prove to me that I am insane, for my mind has the same defect that afflicts his... When I look around me, I am often troubled to see how many people are mad." [7]

- "[The human] race, in its poverty, has unquestionably one really effective weapon—laughter."[8]

- "If the Eiffel Tower were now representing the world's age, the skin of paint on the pinnacle-knob at its summit would represent man's share of that age; and anybody would perceive that that skin was what the tower was built for. I reckon they would, I dunno." -Letters from the Earth

- "I do not take any credit to my better-balanced head because I never went crazy on Presbyterianism. We go too slow for that. You never see us ranting and shouting and tearing up the ground, You never heard of a Presbyterian going crazy on religion. Notice us, and you will see how we do. We get up of a Sunday morning and put on the best harness we have got and trip cheerfully down town; we subside into solemnity and enter the church; we stand up and duck our heads and bear down on a hymn book propped on the pew in front when the minister prays; we stand up again while our hired choir are singing, and look in the hymn book and check off the verses to see that they don't shirk any of the stanzas; we sit silent and grave while the minister is preaching, and count the waterfalls and bonnets furtively, and catch flies; we grab our hats and bonnets when the benediction is begun; when it is finished, we shove, so to speak. No frenzy, no fanaticism —no skirmishing; everything perfectly serene. You never see any of us Presbyterians getting in a sweat about religion and trying to massacre the neighbors. Let us all be content with the tried and safe old regular religions, and take no chances on wildcat. (from "The New Wildcat Religion")

Bibliography

- (1867) Advice for Little Girls (fiction)

- (1867) The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (fiction)

- (1868) General Washington's Negro Body-Servant (fiction)

- (1868) My Late Senatorial Secretaryship (fiction)

- (1869) The Innocents Abroad (non-fiction travel)

- (1870-71) Memoranda (monthly column for The Galaxy magazine)

- (1871) Mark Twain's (Burlesque) Autobiography and First Romance (fiction)

- (1872) Roughing It (non-fiction)

- (1873) The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (fiction)

- (1875) Sketches New and Old (fictional stories)

- (1876) Old Times on the Mississippi (non-fiction)

- (1876) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (fiction)

- (1876) A Murder, a Mystery, and a Marriage (fiction); (1945, private edition), (2001, Atlantic Monthly).[9]

- (1877) A True Story and the Recent Carnival of Crime (stories)

- (1878) Punch, Brothers, Punch! and other Sketches (fictional stories)

- (1880) A Tramp Abroad (non-fiction travel)

- (1880) 1601 (Mark Twain)|1601: Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors]] (fiction)

- (1882) The Prince and the Pauper (fiction)

- (1883) Life on the Mississippi (non-fiction)

- (1884) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (fiction)

- (1889) A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (fiction)

- (1892) The American Claimant (fiction)

- (1892) Merry Tales (fictional stories)

- (1893) The £1,000,000 Bank Note and Other New Stories (fictional stories)

- (1894) Tom Sawyer Abroad (fiction)

- (1894) Pudd'nhead Wilson (fiction)

- (1896) Tom Sawyer, Detective (fiction)

- (1896) Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (fiction)

- (1897) How to Tell a Story and other Essays (non-fictional essays)

- (1897) Following the Equator (non-fiction travel)

- (1900) The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg (fiction)

- (1901) Edmund Burke on Croker and Tammany (political satire)

- (1902) A Double Barrelled Detective Story (fiction)

- (1904) A Dog's Tale (fiction)

- (1905) King Leopold's Soliloquy (political satire)

- (1905) The War Prayer (fiction)

- (1906) The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories (fiction)

- (1906) What Is Man? (essay)

- (1907) Christian Science (non-fiction)

- (1907) A Horse's Tale (fiction)

- (1907) Is Shakespeare Dead? (non-fiction)

- (1909) Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven (fiction)

- (1909) Letters from the Earth (fiction, published posthumously)

- (1910) Queen Victoria's Jubilee (non-fiction, published posthumously)

- (1916) The Mysterious Stranger (fiction, possibly not by Twain, published posthumously)

- (1924) Mark Twain's Autobiography (non-fiction, published posthumously)

- (1935) Mark Twain's Notebook (published posthumously)

- (1969) The Mysterious Stranger (fiction, published posthumously)

- (1992) Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-Imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. Jim Zwick, ed. (Syracuse University Press) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5 ((previously uncollected, published posthumously)

- (1995) The Bible According to Mark Twain: Writings on Heaven, Eden, and the Flood (published posthumously)

See also

- Bernard DeVoto

- Local color

- Mark Twain Award

- Mark Twain House

- Mark Twain in popular culture

- Mark Twain Memorial Bridge

- Mark Twain Prize for American Humor

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Life on the Mississippi, chapter 50

- ↑ Kaplan, Fred (October 2003). "Chapter 1: The Best Boy You Had 1835-1847", The Singular Mark Twain. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47715-5. . Cited in "Excerpt: The Singular Mark Twain". About.com: Literature: Classic. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ↑ Mark Twain Quotations - Vivisection. Retrieved September 3, 2006.

- ↑ Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-Imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. (1992, Jim Zwick, ed.) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5

- ↑ Lauber, John. The Inventions of Mark Twain: a Biography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1990.

- ↑ http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Mark_Twain#India

- ↑ Christian Science by Mark Twain; full text ebook here

- ↑ The Mysterious Stranger by Mark Twain. full text ebook here The Mysterious Stranger is difficult to attribute, as it is an unifinished novel, and exists in at least 4 largely different versions. However, the quote is in the version available at Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ Barber, Greg (2001-06-25). A Mysterious Manuscript (HTML). Mark Twain: Media Watch Special Report. PBS Online News Hour. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

External links

- Works by Mark Twain. Project Gutenberg. More than 60 texts are freely available.

- Mark Twain Quotes, Newspaper Collections and Related Resources

- Twain on The Awful German Language

- Complete text of No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

- Audio book recording with accompanying text of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

- Many Twain stories are read in Mister Ron's Basement (Number 431 — Celebrated Jumping Frog, Numbers 195-199, Number 146 — Million Pound Banknote, Nos. 67-71, and Number 6 — The War Prayer) Podcast

- The Mark Twain Papers and Project of the Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley. Home to the largest archive of Mark Twain's papers and the editors of a critical edition of all of Mark Twain's writings.

- Mark Twain Room (Houses original manuscript of Huckleberry Finn)

- The University of California Press Publishers of the critical edition of Mark Twain's writings.

- Elmira College Center for Mark Twain Studies

- Ever the Twain Shall Meet, a guide to Mark Twain on the Web

- "The Mark Twain they didn’t teach us about in school", by Helen Scott, from International Socialist Review 10, Winter 2000, pp.61-65.

- Full text of the biography Mark Twain by Archibald Henderson

- The Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT

- The Mark Twain Boyhood Home in Hannibal, MO

- The Hannibal Courier Post A Look at the Life and Works of Mark Twain

- Mark Twain: Known To Everyone—Liked By All, a Ken Burns film shown on PBS.

- Literary Pilgrimages—Mark Twain sites

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.