Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick (5th century C.E.) was a Christian missionary involved in the evangelization of Ireland. Born in Britain but captured as a youth by Irish warriors, it is said that Patrick was called by God to escape from his slavery. He fled to Europe where he studied at a monastery to become a missionary. Eventually consecrated as a Bishop, he returned to Ireland to spread the Gospel to the people.

Many legends are told about St. Patrick's activities in Ireland including the story that he used the three-leaf shamrock to teach the masses about the Holy Trinity. It is also said that he banished all serpents from the island. Today, St. Patrick is celebrated as Ireland's patron saint.

History

Birth and Early Life

The exact location of Saint Patrick's birthplace is uncertain. His own writing, Confessio identifies his birthplace as the town of vico banavem in Taburnia. However, the location of this town has never been identified, Many think that St. Patrick was born somewhere along the west coast of Scotland. Suggested sites for his birthplace include Dumbarton, Furness[1], Somerset, and Kilpatrick.

Patrick was born during the 5th century when Britain was undergoing turmoil following the withdrawal of Roman troops. Roman central authority was collapsing. Having been under the Roman cloak for over 350 years, the Romano-British were having to look after themselves. Populations were on the move, and the recently converted British Christians were being colonized by pagan Anglo-Saxons. In this context, Patrick was swept away by Irish marauders, when he was only sixteen years old, along with "thousands" of other people, and sold as a slave. He was sold to an especially cruel master who was a Druid priest by the name of Milchu. Patrick's captivity lasted for six years and though harsh, it availed him to the mastery of the Celtic culture and language. It was there, on the hillsides and woodlands near Ballymena, where Patrick tended sheep, that he formed a profound relationship with God. Patrick stated "The love of God and his fear grew in me more and more, as did the faith, and my soul was roused, so that, in a single day, I have said as many as a hundred prayers and in the night, nearly the same. I prayed in the woods and on the mountain, even before dawn. I felt no hurt from the snow or ice or rain."[2]

It is said that one day an angel appeared to him in a dream and admonished him, telling him to leave the druids place of servitude. In obedience, he escaped, traveling for about 200 miles by foot. When he reached Westport, a city along the coast, he boarded a ship and sailed on the Irish Sea back to Britain. Although he was back with friends, his heart was in service to God. His zeal for a religious life led him to Auxerre, France. There Patrick studied under St. Germaine of Auxerre for eighteen years and was appointed into the Priesthood. St. Germaine recommended the new Priest to Pope Celestine who gave St. Patrick his name "Patecius" or "Patritius". It later became "Pater Civium" (the father of his people).

Patrick's return to Ireland

Patrick longed to return to Ireland. This desire became a reality when St. Germaine asked him to go on to Erin, (another name for Ireland) as a missionary.

Around the year 432 C.E., Patrick and his companions arrived in hostile Irish territory at the mouth of Vantry River. Patrick visited Ballymena where he had been a slave. He sent word to his former master, Milchu, that in payment for his cruelty and the years of Patrick’s servitude, he was to receive blessing and freedom as God's child. However, when Milchu learned of the Irish apostles coming, he was afraid and committed suicide.

Mission

His first converted patron was Saint Dichu, a Druid priest, who raised his sword to kill Patrick, was paralyzed and unable to strike. This experience created in Dichu respect and loyalty toward Patrick, and he made a gift of a large sabhall (barn) for a church sanctuary. This first sanctuary became, in later years, his chosen retreat. A monastery and church were erected there, and there Patrick died; the site, Saul County Down, retains the name Sabhall (pronounced "Sowel").

The Episcopal see at Armagh was organized by Patrick. The choice of Armagh may have been determined by the presence of a powerful king. There Patrick had a school and presumably a small familia in residence; from this base he made his missionary journeys. He established the churches into territorial sees, as was common in both the East and West. He encouraged the Irish to dedicate themselves to God by becoming monks and nuns although it took many centuries before the monastery was the principal unit of the Irish Church.

Patrick gathered many followers, including Saint Benignus, who would later become his successor. His chief concerns were the raising up of native clergy, and abolishing Paganism, idolatry, and Sun-worship. He made no distinction of classes in his preaching and was himself ready for imprisonment or death. He was the first writer to condemn all forms of slavery.

However, Patrick frequently wrote that he expected to be violently killed or enslaved again. His Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus protesting British slave trading and the stance he took against the slaughter of Irish Christians by Coroticus's Welshmen put his life in danger. This is the first identified literature of the British or Celtic Catholic Church.[3]

Although Patrick was not the first Christian missionary to evangelize Ireland, tradition accords him with the most impact. Men such as Secundus and Palladius were active there before him. Patrick's missionary work was concentrated mostly in the provinces of Ulster and Connaught, which had little familiarity with Christianity. Patrick traveled extensively throughout the country preaching, teaching, building churches, opening schools and monasteries, and converting chiefs and Bards. He is said to have consecrated 350 Bishops. It is also alleged that his preaching was supported with miracles.

Death: a contentious date

Patrick died in 493 C.E. according to the latest reconstruction of the old Irish annals. Prior to the 1940s it was believed without doubt that he died in 461 and thus had lived in the first half of the 5th century. However, a lecture entitled "The Two Patricks", published in 1942 by T. F. O'Rahilly, caused enormous controversy by proposing that there had been two "Patricks", Palladius and Patrick, and that what we now know of St. Patrick was in fact in part a conscious effort to meld the two into one hagiographic personality. Decades of contention eventually ended with most historians now asserting that Patrick was indeed most likely to have been active in the mid-to-late 5th century.

The compiler of the Annals of Ulster stated that in the year 553:

- I have found this in the Book of Cuanu: The relics of Patrick were placed sixty years after his death in a shrine by Colum Cille. Three splendid halidoms were found in the burial-place: his goblet, the Angel's Gospel, and the Bell of the Testament. This is how the angel distributed the halidoms: the goblet to Dún, the Bell of the Testament to Ard Macha, and the Angel's Gospel to Colum Cille himself. The reason it is called the Angel's Gospel is that Colum Cille received it from the hand of the angel.

The placement of this event under the year 553 would certainly seem to place Patrick's death in 493, or at least in the early years of that decade.

For most of Christianity's first 1,000 years, canonizations were done on the diocesan or regional level. Relatively soon after very holy people died, the local Church affirmed that they could be liturgically celebrated as saints. [4] For this reason, St. Patrick was never formally canonized by the Pope.

Legends

There are many legends associated with the life of St. Patrick, which helped to promote the Roman Catholic faith among the Irish population.

It is said that Ireland at the time of St. Patrick was a land of many idols. The most famous of these was called Crom Crauch located in Leitrim. This idol was a huge rock, overlaid in gold, surrounded by twelve brass covered stones, representing the sun, moon, and stars. People would offer their firstlings and other sacrifices to this idol. Patrick was said to have thrown down Crom Crauch with the "staff of Jesus", and to call out its demons.

Another famous story is told of the annual vernal fire lit by the High King of Ireland at Tara. All the fires were to be extinguished so they could be renewed from the sacred fire from Tara. Patrick lit a rival, miraculously inextinguishable Christian bonfire on the hill of Slane, at the opposite end of the valley.

Pious legend also credits Patrick with banishing snakes from the island. Since post-glacial Ireland never actually had snakes it is certain that "snakes" were used as a symbol. [5]; One suggestion is that snakes referred to the serpent symbolism of the Druids of that time and place. One could find such symbol on coins minted in Gaul. It could also have referred to beliefs such as Pelagianism, symbolized as "serpents."

Legend also credits Patrick with teaching the Irish about the concept of the Trinity by showing them the shamrock, a three-leaved clover. Through this example, Patrick highlighted the Christian dogma of 'three divine persons in the one God' (as opposed to the Arian belief that was popular in Patrick's time).

Writings

The major writings of St. Patrick's life are his "Confessio," (Confessions), his Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus ("Epistola ad Coroticum"), and his "Breast-Plate Prayer" (also called the Fáed Fíada), which was thought to have been written to mark the end of paganism in Ireland.

The full text of the Breast-Plate Prayer is as follows:

- I bind to myself today:

- The strong virtue of the Invocation of the Trinity:

- I believe the Trinity in the Unity

- The Creator of the Universe.

- I bind to myself today:

- The virtue of the Incarnation of Christ with His Baptism,

- The virtue of His crucifixion with His burial,

- The virtue of His Resurrection with His Ascension,

- The virtue of His coming on the Judgment Day.

- I bind to myself today:

- The virtue of the love of seraphim,

- In the obedience of angels,

- In the hope of resurrection unto reward,

- In prayers of Patriarchs,

- In predictions of Prophets,

- In preaching of Apostles,

- In faith of Confessors,

- In purity of holy Virgins,

- In deeds of righteous men.

- I bind to myself today:

- The power of Heaven,

- The light of the sun,

- The brightness of the moon,

- The splendor of fire,

- The flashing of lightning,

- The swiftness of wind,

- The depth of sea,

- The stability of earth,

- The compactness of rocks.

- I bind to myself today:

- God's Power to guide me,

- God's Might to uphold me,

- God's Wisdom to teach me,

- God's Eye to watch over me,

- God's Ear to hear me,

- God's Word to give me speech,

- God's Hand to guide me,

- God's Way to lie before me,

- God's Shield to shelter me,

- God's Host to secure me,

- Against the snares of demons,

- Against the seductions of vices,

- Against the lusts of nature,

- Against everyone who meditates injury to me,

- Whether far or near,

- Whether few or with many.

- I invoke today all these virtues

- Against every hostile merciless power

- Which may assail my body and my soul,

- Against the incantations of false prophets,

- Against the black laws of heathenism,

- Against the false laws of heresy,

- Against the deceits of idolatry,

- Against the spells of women, and smiths, and druids,

- Against every knowledge that binds the soul of man.

- Christ, protect me today:

- Against every poison, against burning,

- Against drowning, against death-wound,

- That I may receive abundant reward.

- Christ with me, Christ before me,

- Christ behind me, Christ within me,

- Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

- Christ at my right, Christ at my left,

- Christ in the fort,

- Christ in the chariot seat,

- Christ in the poop [deck],

- Christ in the heart of everyone who thinks of me,

- Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks to me,

- Christ in every eye that sees me,

- Christ in every ear that hears me.

- I bind to myself today

- The strong virtue of an invocation of the Trinity,

- I believe the Trinity in the Unity

- The Creator of the Universe.[1]

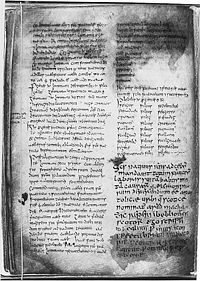

Additionally, a 9th century Irish manuscript known as the Book of Armagh (Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS 52) is a was thought to have belonged to St. Patrick and, at least in part, to be a product of his hand. The manuscript is also known as the Canon of Patrick and contains important early texts relating to St. Patrick. These include two Lives of St. Patrick, one by Muirchu Maccu Machteni and one by Tirechan. Both texts were originally written in the 7th century. The manuscript also includes other miscellaneous works about St. Patrick including the Liber Angueli (or the Book of the Angel), in which St. Patrick is given the premarital rights of Armagh by an angel.

The people of medieval Ireland placed a great value on this manuscript. It was one of the symbols of the office for the Archbishop of Armagh.

Other Accolades

The Orthodox Church, especially English speaking orthodox Christians living in the British Isles as well as in North America, also venerate St. Patrick. There have even been icons dedicated to him[6].

He is recognized today as the patron saint of Ireland along with Saint Brigid and Saint Columba, and is also considered to be the patron saint of excluded people. His feast day is March 17th.

St. Patrick is also credited with fostering the development of arts and crafts and introducing the knowledge of the use of lime as mortar in Ireland. He is responsible for the initial construction of clay churches in Ireland in the 5th century C.E.. Another of St. Patrick's achievements was teaching the Irish to build arches of lime mortar instead of dry masonry. These beginnings of ceramic work developed into organized crafts, and that is how St. Patrick became a patron saint of engineers. [7]

St. Patrick is also known as the Patron Saint of Nigeria. Nigeria was evangelized primarily by Irish missionaries and priests from Saint Patrick's Missionary Society known as the Kiltegan Missionaries.

Footnote

- 1. Patrick Francis Moran, "St. Patrick," Catholic Encyclopedia (1911), Volume XI Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bieler, L. ed., Works of Saint Patrick, St. Secundus: Hymn on St. Patrick, Paulist Press, 1978.

- Bury, J. B. "The Life of St. Patrick and his Place in History, Dover Publications, 1998. ISBN: 0486400379

- Cahill, Thomas. How the Irish Saved Civilization, ISBN: 0385418493 Anchor, 1996.

- Freeman, P. St. Patrick of Ireland: A Biography, Simon & Schuster, 2004. ISBN: 0743256328

- Hanson, R. P. C. Saint Patrick: His Origins and Career, Oxford, 1997. ASIN: B000KBLG52

- Moran, Patrick Francis. "St. Patrick," Catholic Encyclopedia (1911), Volume XI (Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

- Skinner, John. Confession of Saint Patrick, New York: Image, 1998. ISBN: 0385491638

External Sources

- NewAdvent.org: St. Patrick

- Catholic.org: St. Patrick

- Saint Patrick Centre: Saint Patrick's Legacy

- MSN Encarta: Saint Patrick

- HistoryChannel.com: Who Was St. Patrick?

- IrishAbroad.com: Life and History of St. Patrick

- AmericanCatholic.org: The Real St. Patrick and Celtic Spirituality

- Slate.com: St. Patrick Revealed

- Saint Patrick in Orthodoxy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Patrick Francis Cardinal Moran, "St. Patrick," Catholic Encyclopedia (1911), Volume XI (Robert Appleton Company, 1911.)