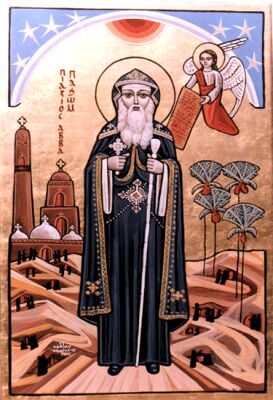

Saint Pachomius

Saint Pachomius (ca. 292-346), also known as Abba Pachomius and Pakhom, is generally recognized as the founder of cenobitic (communal) Christian monasticism. His innovative monastic structure and teaching methods made the ascetic Christian life a reality for tens of thousands of Christians. All later Catholic and Orthodox religious orders (from Franciscans to Cistercians) are, to an extent, products of his initial innovation.

In all world religions, Saints (from the Latin: "sanctus" meaning "holy" or "consecrated") are known for their spiritually exemplary character and love of the divine. Saints are known for their devotion to God as well as for their commitment to virtuous living. They encourage ordinary believers to strive to become closer to God and to be better people by providing an uplifting example of spiritual and moral conduct.

The Life of Pachomius

Background Information

In the third and fourth centuries C.E., a new spiritual innovation began to become popular among devoted Christians. The deserts of Egypt and Syria, which had once been a refuge for the persecuted, began to be considered a home, a destination where devoted Christians could - in imitatio Christi - prove their dedication to Jesus and the Gospel through intense ascetic sacrifice. Though the actual persecution of Christians had largely ceased by this time, these "'athletes of Christ' … regarded their way of life as simply carrying on the norm of Christian life in pre-Constantinian times, when to be a Christian was a matter of real seriousness."[1] These early religious heroes, of whom Saint Anthony (251-356) is likely the most prominent example, became the new spiritual ideals for the lay public: people whose devotion to the Lord allowed them to accomplish superhuman feats of courage, faith and stamina. [For more information, see Desert Fathers.]

Biography/Hagiography

Pachomius was born in 292 in Thebes (Luxor, Egypt) to pagan parents.[2] According to his hagiography, he was swept up in a Roman army recruitment drive at the age of 20 against his will and held in captivity, a common occurrence during the turmoils and civil wars of the period. It was here that he first came into contact with Christianity, in the form of local Christians who visited each day to provide succor to the inmates. This made a lasting impression on the imprisoned Pachomius and he vowed to investigate this foreign tradition further when he was freed. As fate would have it, he was soon released (when Constantine took control of the Roman army in the area), and, remembering his vow, Pachomius was soon converted and baptized (314). Hearing tales of the spiritual excellence of the Desert Fathers, he decided to follow them into the desert to pursue the ascetic path. In doing so, he sought out the hermit Palamon and came to be his follower (317).

In his travels through the desert, Pachomius chanced upon an abandoned town called Tabennesi. There, he heard a message from the Heavens: "Pachomius, Pachomius, struggle, dwell in this place and build a monastery; for many will come to you and become monks with you, and they will profit their souls."[3] After receiving this calling, he converted the town into a monastic community (318(?)-323(?)). The first to join him was his elder brother John, but soon more than 100 monks had taken up residence there. In the years to follow, he came to build an additional six or seven monasteries and a nunnery.

Though Pachomius sometimes acted as lector for nearby shepherds, neither he or any of his monks became priests. Regardless, he remained abbot to the cenobites for some forty years, until he fell victim to an epidemic disease (probably plague). Knowing that the end of his life was at hand, he called the monks, strengthened their faith, and appointed his successor. He then departed in peace on May 15, 346.

From his initial monastery, demand quickly grew and, by the time of his death in 346, one count estimates there were 3000 monasteries throughout Egypt from north to south. Within a generation after his death, this number grew to 7000 and then spread into Palestine, the Judean Desert, Syria, North Africa and eventually Western Europe.[4]

Pachomius and the Development of Cenobitic Monasticism

Until the time of Pachomius, Christian asceticism had been solitary or eremitic. Male or female monastics lived in individual huts or caves and met only for occasional worship services. The Pachomian innovation was to create the community or cenobitic organization, in which male or female monastics lived together and had their possessions in common under the leadership of an abbot or abbess. Indeed, his genius was to transform the monastic fervor of the Desert Fathers into a socialized and sustainable religious lifestyle. Further, this approach enabled the monastics (themselves religious exemplars) to interact (and thus positively impact) surrounding Christians, who settled around the monks as lay disciples. In this way, he set the stage for the Christian monastic movements that followed, the vast majority of which existed in concert with a surrounding and supportive lay community.

The Pachomian community was initially created using its founder's personal charisma to maintain structure and order. Pachomius himself was hailed as "Abba" (father), and his followers "considered him trustworthy," [and that] "he was their father after God."[5] However, in the years that followed (especially after the death of their founder), the Pachomian monks began to collect and codify his edicts, a process that eventually yielded the collected Rules of his order. Intriguingly, a parallel process of rule development was occurring simultaneously in Caesarea, where St. Basil, who had visited the Pachomian order, was in the process of adapting the ideas he inherited from Pachomius into his own system of monastic order. His rules, the Ascetica, are still used today by the Eastern Orthodox Church, and are comparable to the Rule of Saint Benedict in the West.

Pedagogical use of moral exemplars

As mentioned above, Pachomius strove to indoctrinate his brother monks (and the resident laity) into a righteous lifestyle. One of the innovative means that he used to achieve that end was an extensive use of moral exemplars in his pedagogy. Intriguingly (and unlike many earlier teachers), it is notable that he did not restrict this to the imitation of Christ. To demonstrate the proper attitude when facing solitude, he uses an Old Testament example: "Let us then draw courage from these things, knowing that God is with us in the desert as he was with Joseph in the desert. Let us … , like Joseph, keep our hearts pure in the desert."[6] In describing the psychic preparations that must take place before Passover, he suggests a constant remembrance of Christ: "Let those who practice askesis labour all the more in their way of life, even abstaining from drinking water…; for he asked for a bit of water while he was on the cross and he was given vinegar mixed with gall."[7] Finally, concerning the proper mode of moral instruction, he says to his monks: "My son, emulate the lives of the saints and practice their virtues."[8] In all of these cases, Pachomius demonstrates the importance of living an ascetic life, constantly striving for moral rectitude. He helps to make this difficult process more accessible by using exemplars from within the religious tradition of his listeners, showing that this ascetic devotion to God is, in fact, an achievable human reality.

Notes

- ↑ S. P. Brock, "Early Syrian Asceticism," Numen Vol. XX (1973): 1-19. 2.

- ↑ A particularly hagiographical detail, found in the Bohairic version of the Life of Pachomius, suggests that the young Pachomius was, in some fundamental way, "pre-selected" for membership in the Christian community. Though he had pagan parents, all attempts to encourage him to take part in their worship proved ultimately futile: "As a child his parents took him with them to sacrifice to those [creatures] that are in the waters. When those [creatures] raised their eyes in the water, they saw the boy, took fright and fled away. Then the one who was presiding over the sacrifice shouted, 'Chase the enemy of the gods out of here, so that they will cease to be angry with us, for it is because of him that they do not come up.' … And his parents were distressed about him, because their gods were hostile to him." "The Boharic Life of Pachomius," Pachomian Koinonia I: The Life of Saint Pachomius, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications Inc., 1980), 25.

- ↑ "The Boharic Life of Pachomius," 39. Given the laudatory nature of hagiographical writing, it is notable that the previous sections of the Life make extensive efforts to demonstrate that Pachomius himself was utterly capable of enduring and, in fact, comfortable with the extreme asceticism practiced by Palamon. This means that decision to create a monastery can only be credited to the most noble (and selfless) motives.

- ↑ Dr. Kenneth W. Harl. The World of Byzantium. (The Teaching Company (audio cassette) ISBN 16585800X / B000H9BZAI, 2001)

- ↑ Philip Rousseau. Pachomius: The Making of a Community in Fourth-Century Egypt. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985), 67.

- ↑ Pachomius, Letter 8, in Pachomian Koinonia III. (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1982), 72.

- ↑ Pachomius, "Pachomian Instruction 2," in Pachomian Koinonia (Vol. 3), (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1982), 48.

- ↑ Pachomius, "Pachomian Instruction 1," in Pachomian Koinonia (Vol. 3), (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1982), 14.

See also

- Saint Benedict

- Desert Fathers

Bibliography

- Bacchus, F. J. "Pachomius" in The Catholic Encyclopedia. Accessed online at: [1].

- Brock, S. P. "Early Syrian Asceticism." Numen Vol. XX, 1973. 1-19.

- Goehring, James E. "Withdrawing from the Desert: Pachomius and the Development of Village Monasticism in Upper Egypt." Harvard Theological Review 89(3) (1996): 267-285.

- Pachomius. Pachomian Koinonia (Vol. 3). Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1982.

- Palladius. "Lausiac History." Internet Medieval Sourcebook. 2000. [2].

- Rousseau, Philip. Pachomius: The Making of a Community in Fourth-Century Egypt. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985.

External Links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- The Rule Of Pachomius: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, & Part 4

- Coptic Orthodox Synaxarium (Book of Saints)

- St. Pachomius (Catholic Encyclopedia)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.