Peasant

The word peasant, from fifteenth century French païsant meaning one from the pays, the countryside or region, (from Latin pagus, country district) is an agricultural worker with roots in the countryside in which he or she dwells, either working for others or, more specifically, owning or renting and working by his or her own labour a small plot of ground, in England a "cottager." The term has historically meant Euopean land workers, although perhaps 80% of the world's population could be termed "peasant." Much contemporary thought is based on the European experience alone, though there is variation in the continued development of farm workers around the world.

Background

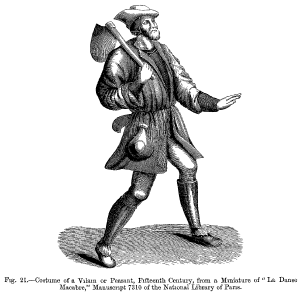

Historically, peasant is a word for farmer. But in the world before the development of individual ownership, free trade and democracy to be a peasant meant to stay alive. All land was owned by various aristocracy or state govenments, and as the modern division of labor and industry had not developed, it was the way to have access to land to cultivate and to be able to eat. A peasant had to be a jack-of-all trades, handy at everything. Peasants depended on their land. (illustration, above right). Peasants lived within agricultural time; the "world-time," in Fernand Braudel's term, of politics and economics did not directly affect the peasant. Peasants typically made up the majority of the population. In modern society, where a market economy has taken root, the term may be more loosely referring to the traditionalist rural population where land is chiefly held by smallholders, peasant proprietors.

A rural peasant population differs enormously in its values and economic behavior from an urban worker population. Peasants tend to be more conservative than urbanites, and are often very loyal to inherited power structures that define their rights and privileges and protect them from interlopers, despite their generally lower status within them.

Peasant societies developeded strong social support networks. Especially in harder climates, members of the community who had a poor harvest or suffered some form of hardship often have been taken care of by the rest of the community. Loyalties and vengeance both ran very deep. Peasant communities can be difficult to access or understand by outsiders.

Peasant societies often have had very stratified social hierarchies within them.

Some commentary has been made that in a barter economy, peasants characteristically had a different attitude to work than peasants— or towndwellers— in a money economy would. Often such societies have been markedly less competative.

Fernand Braudel devoted the first volume of his major work, Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century to the largely silent and invisible world that existed below the market economy, in The Structures of Everyday Life.

Since the literate classes who left the most record tended to dismiss the peasants as figures of coarse appetite and rustic comedy, "peasant" may have had a pejorative rather than descriptive connotation in historical memory. However, it was not always that way; peasants were once viewed as pious and seen with respect and pride. Life was hard for peasants, but before modern technology and a money economy, life was hard for everyone. Society was theorized as organized in three "estates": those who work, those who pray and those who fight.

The position of the medieval European Peasant diverges

The relative position of Western European peasants greatly improved after the Black Death unsettled medieval Europe, granting far greater economic and political power to those peasants fortunate enough to survive the cataclysm. In the wake of this disruption to the established hierarchy, later centuries saw the invention of the original printing presses, widespread literacy and the enormous social and intellectual changes of the Enlightenment. This evolution of ideas in an environment of relatively widespread literacy laid the groundwork for the Industrial Revolution, which enabled mechanically and chemically augmented agricultural production while simultaneously increasing the demand for factory workers in cities. These factory workers with their low skill and easy replaceability quickly came to occupy the same socio-economic stratum as the original medieval peasants. The tension between the interests of these two groups forms an underlying context for much of the social and economic debate of the past century and a half. Unfortunately, much of this dialogue was exported to regions that were culturally very different from 19th/20th century Western Europe.

This is especially pronounced in Eastern Europe. Lacking any catalysts for sweeping change in the 14th century, the Eastern European peasants largely continued upon the original medieval path until the 18th and 19th centuries, when the tsars began to notice that the West had made enormous strides they had not. They responded by forcing the largely illiterate peasant populations under their control to embark upon a Westernization and industrialization campaign. Using methods of coercion and inept central planning that were largely continued by the later Communists, Peter the Great initiated a half-successful attempt to force 500+ years worth of social change in the space of a few generations. Although this approach eventually (under the Communists) produced a technologically advanced and literate population, it came at the cost of many millions of lives and a cultural legacy that persists to this day.

Peasant Revolts

Peasant, Peasants' or Popular is variously paired with Revolt, Uprising and War and may refer to (sorted chronologically):

- Peasant revolt in Flanders 1323-1328

English peasants' revolt of 1381

The revolt was precipitated by heavy-handed attempts to enforce the third poll tax, first levied in 1377 supposedly to finance military campaigns overseas — a continuation of the Hundred Years' War initiated by King Edward III of England. The Black Death had greatly reduced the labour force, and as a consequence, the labourers had been able to demand enhanced terms and conditions. The Statute attempted to curb this by pegging wages and restricting the mobility of labour. Probably those labourers employed by lords were effectively exempted, but those labourers working for other employers, both artisans and more substantial peasants, were liable to be fined or held in the stocks.

n June 1381, two groups of common people from the southeastern counties of Kent and Essex marched on London. "Wat" Tyler, was at the head of a contingent from Kent. When the rebels arrived in Blackheath, London on June 12, the renegade Lollard priest, John Ball, preached a sermon including the famous question that has echoed down the centuries: "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?"John Ball (priest)#Footnotes|[1]. The rebels were encouraged by this, and crossed London Bridge into the heart of the city the next day while the 'Men of Essex' had gathered with Jack Straw had marched on London, arriving at Stepney. They began a systematic attack on certain properties, many of them associated with John of Gaunt and/or the Knights of Hospitaller Order. On June 14, they are reputed to have been met by the young king himself, and to have presented him with a series of demands, including the dismissal of some of his more unpopular ministers and the effective abolition of serfdom.

Meanwhile, a group of rebels stormed the Tower of London— after likely being let in— and summarily executed those hiding there. Richard II of England agreed to reforms such as fair rents, and the abolition of serfdom.

- Slovenian peasant revolt of 1515

German peasants war of 1524-1525

The Peasants' War (in German, der Deutsche Bauernkrieg) was a popular revolt in Europe, specifically in the Holy Roman Empire between 1524-1525. It consisted, like the preceding Bundschuh movement and the Hussite Wars, of a mass of economic as well as religious revolts by peasants, townsfolk and nobles. The movement possessed no common programme.

The conflict, which took place mostly in southern, western and central areas of modern Germany but also affected areas in neighbouring modern Switzerland and Austria, involved at its height in the spring and summer of 1525 an estimated 300,000 peasant insurgents: contemporary estimates put the dead at 100,000. The revolt was in many respects a direct consequence of the Protestant reformation, which taught that all people were valued by God and could access God directly without the need of priestly mediation. For some Protestants, this meant that the church should be governed by the people, not by a clerical elite. Some translated this into the political realm, arguing that all people, regardless of social rank, should participate in governance. While Martin Luther upheld the power of the princes, believing that society needed to be policed in order to prevent chaos and moral laxity, other reformers took a different view. Thomas Müntzer, the anabaptist leader, wanted to created a Utopian society ruled by God as a stepping-stone for the creation of God's kingdom. Any distinction between the spiritual and the temporal realms were false. However, he took his ideas to the extreme and resorted to physical force to oppose all constituted authorities, attempting to establish by force his ideal Christian commonwealth, with absolute equality and the community of goods. One result of the failed revolt was increasing unease with the traditional alliance between religion and the state. The conviction grew that religion was best left to private choice, that subjects and citizens have the right to practice their religion as well as to have no religion but that the state should not intervene in either case. On a positive note, this recognized that religious freedom is a fundamental right, so that eventually most measures that privileged some Churches over others, as well as restrictions on the religious and civil liberty of Jews and others, were abolished. Negatively, this made it more difficult for people of religious conviction to argue in the public square in defense of their religion's moral and ethical standards; this is regarded as attempting to impose religion on those who do not wish to be religious, or a morality on people who do not share the same views of right and wrong. Marxists, interested in the element of class struggle, see Thomas Müntzer as a hero of the proletariat whose ideas eventually saw fruition in the Maxist state of what was formerly East Germany [1]

- Croatian and Slovenian peasant revolt

- Swiss peasant war of 1653

- 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1973 to the present

- Braudel, Fernand, The Structures of Everyday Life vol I of Civilization and Capitalism

- Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy, Montaillou : The Promised Land of Error

- Mollat, Michael, The Poor in the Middle Ages, 1986.

- Kishlansky, Mark, Civilization in the West, fourth edition, 2001

External links

- Jerome Blum, Lord and Peasant in Russia From the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century (Princeton University Press, 1961).

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ 'Apocalpticism Explained: Thomas Müntzer', PBS retrieved 21-01-2007 http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/apocalypse/explanation/muentzer.html