Difference between revisions of "Nathan Bedford Forrest" - New World Encyclopedia

Lindsay Hull (talk | contribs) |

Lindsay Hull (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| − | Nathan Bedford Forrest was born in a primitive [[log cabin]] to a poor family in [[Chapel Hill, Tennessee]]. At the time, the area was referred to as Duck River country.<ref>Jack Hurst, ''Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography'' (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1993), 115.</ref> People living in the area had no modern means of manufacture and created everything by hand. Few acquired any skills beyong the basics for writing, reading, and performing simple math. Forrest was descendent of Shadrack Forest, a wealthy farmer and slave owner from [[Virginia]] who moved first to [[North Carolina]] around 1730 and later relocated again to [[Tennessee]] 76 years later in 1806 with his second son, Nathan. In the next few generations this branch of the family would lose its wealth and essentially become pioneers. Nathan was married to a Miss Baugh whose family had settled in [[North Carolina]] after initially entering the [[United States]] from [[Ireland]].<ref> John A. Wyeth, ''That Devil Forest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forest'' (New York: Harper & Brothers Pub., 1959), 2.</ref> Their eldest son William, born around 1798, was the father of Lieut-Gen. N.B. Forrest. William was twenty-one when his eldest son was born. Forrest was the first of blacksmith William Forrest's twelve children with Miriam "Maddie" Beck. His mother's ancestors were [[Scotch-Irish]]. Her family had resided in [[South Carolina]] before relocating to Caney Springs in [[Bedford County, Tennessee]] sometime preceeding the Forrest family's migration. They held a considerable amount of property here. Forrest's mother is reputed to have been a strict disiplinarian with her children, once alledgedly taking the switch to one of her a son said to be 18 at the time and an elisted Confederate soldier! Miriam Beck was remarried sometime after William's death to Joseph Luxton with whom she went on to have four additional children. Forrest's first and middle names seem to have been derived from those of his grandfather and the county in which he was born. Forrest had a twin sister named Fanny who would die young of [[typhoid fever]] | + | Nathan Bedford Forrest was born in a primitive [[log cabin]] to a poor family in [[Chapel Hill, Tennessee]]. At the time, the area was referred to as Duck River country.<ref>Jack Hurst, ''Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography'' (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1993), 115.</ref> People living in the area had no modern means of manufacture and created everything by hand. Few acquired any skills beyong the basics for writing, reading, and performing simple math. Forrest was descendent of Shadrack Forest, a wealthy farmer and slave owner from [[Virginia]] who moved first to [[North Carolina]] around 1730 and later relocated again to [[Tennessee]] 76 years later in 1806 with his second son, Nathan. In the next few generations this branch of the family would lose its wealth and essentially become pioneers. Nathan was married to a Miss Baugh whose family had settled in [[North Carolina]] after initially entering the [[United States]] from [[Ireland]].<ref> John A. Wyeth, ''That Devil Forest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forest'' (New York: Harper & Brothers Pub., 1959), 2.</ref> Their eldest son William, born around 1798, was the father of Lieut-Gen. N.B. Forrest. William was twenty-one when his eldest son was born. Forrest was the first of blacksmith William Forrest's twelve children with Miriam "Maddie" Beck. His mother's ancestors were [[Scotch-Irish]]. Her family had resided in [[South Carolina]] before relocating to Caney Springs in [[Bedford County, Tennessee]] sometime preceeding the Forrest family's migration. They held a considerable amount of property here. Forrest's mother is reputed to have been a strict disiplinarian with her children, once alledgedly taking the switch to one of her a son said to be 18 at the time and an elisted Confederate soldier! Miriam Beck was remarried sometime after William's death to Joseph Luxton with whom she went on to have four additional children. Forrest's first and middle names seem to have been derived from those of his grandfather and the county in which he was born. Forrest had a twin sister named Fanny who would die young of [[typhoid fever]].<ref>John Wyeth, 1-12.</ref> |

| − | On the farm his father had worked Forrest would continue the tradition of raising crops and eventually | + | In his youth Forrest demonstrated courage and leadership at a young age, killing a rattlesnake with a stick during a berry-gathering trip with some other youngsters who failed to aid the stick-wielding youth in any way. At 13, Forrest and his family relocated to Tippah County(present-day Benton County) in northern [[Mississippi]]. After his father's death, Forrest became the head of the family at the age of 16, and, through hard work and determination, was able to pull himself and his family up from poverty. He thus became a leader at a young age, taking control over his younger siblings and effectively organizing the household. Two brothers and all three of his sisters would die from typhoid as children leaving behind Forrest and six younger brothers, the youngest born after William's death.<ref>Jack Hurst, 19-22.</ref> |

| − | + | ||

| − | In 1841 (age | + | On the farm his father had worked Forrest would continue the tradition of raising crops and eventually accrued a consideratble amount of livestock. He often worked tirelessly for long hours to see to a successful yield and quickly developed a close familial bond with his brothers. In three years he had provided the family with a very comfortable standard of living.<ref> John Wyeth, 13-14.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | In February 1841, Forrest had ensured his family with enough prosperity that he decided to jourey to Texas where attempts to create the Lone Star Republic were being made. A group of volunteers amassed to come to the assistance of the Texans in a time when Americans were enraptured by the struggle taking place there. Forrest traveled to Houston where he was told that their assistance was not needed and they were instructed to return to their homes. Forrest struggled to earn enough money as a temporary farm hand until he had sufficient funds to return to Mississippi.<ref>Jack Hurst, 22-23.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1842 (age 21), he went into business with his uncle in [[Hernando, Mississippi]] as a cattle and horse trader. His uncle, Jonathan, had earned respect in his profession and Forrest was eager to have the oppurtunity to work with him. Soon he was offered a partnership. In 1845 his uncle was killed there during a dispute with four farmers known as the Matlock brothers, but, after himself being shot and only minorly wounded, Forrest shot and killed two of them with his two shot pistol and wounded the two others with a Bowie knife someone threw to him durring the scuffle. Ironically, one of the wounded men survived and served under Forrest during the Civil War. Forrest continued with the business until 1851. <ref>[http://www.csasilverdollar.com/forrest.html Confederate silver dollar site].</ref> | ||

Forrest was to become a businessman, an owner of several [[plantation]]s and a [[slavery|slave trader]] based on Adams Street in [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]]. In 1858 Forrest (a registered [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrat]]) was elected as a Memphis city [[alderman]].<ref>[http://www.inmotionaame.org/gallery/detail.cfm;jsessionid=8030570241121831204263?migration=3&topic=5&id=342018&type=image&metadata=show&page=&bhcp=1 Domestic slave trade site].</ref> Forrest provided financially for his mother, put his younger brothers through college, and, by the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, he had become a millionaire and one of the richest men in the American South. | Forrest was to become a businessman, an owner of several [[plantation]]s and a [[slavery|slave trader]] based on Adams Street in [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]]. In 1858 Forrest (a registered [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrat]]) was elected as a Memphis city [[alderman]].<ref>[http://www.inmotionaame.org/gallery/detail.cfm;jsessionid=8030570241121831204263?migration=3&topic=5&id=342018&type=image&metadata=show&page=&bhcp=1 Domestic slave trade site].</ref> Forrest provided financially for his mother, put his younger brothers through college, and, by the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, he had become a millionaire and one of the richest men in the American South. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Civil War== |

Forrest earned much of his fortune engaging in the [[slave trade]] (as much as $5,000 per year). Like a majority of Southerners Forrest supported secession for the several causes of taxation levied against the South to support Northern industrialization, states' rights and slavery and supported the [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] (CSA) side in the war. | Forrest earned much of his fortune engaging in the [[slave trade]] (as much as $5,000 per year). Like a majority of Southerners Forrest supported secession for the several causes of taxation levied against the South to support Northern industrialization, states' rights and slavery and supported the [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] (CSA) side in the war. | ||

Revision as of 16:31, 29 June 2007

| Nathaniel Bedford Forrest | |

|---|---|

| July 13 1821 – October 29 1877 (age 56) | |

| |

| Place of birth | Chapel Hill, Tennessee |

| Place of death | Memphis, Tennessee |

| Allegiance | Confederate States of America |

| Service/branch | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861 – 1865 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War • Fort Donelson • Shiloh • First Murfreesboro • Chickamauga • Fort Pillow • Brice's Crossroads • Second Memphis • Nashville • Wilson's Raid |

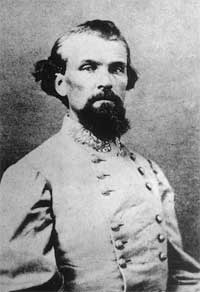

Nathaniel Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821–October 29, 1877) was a Confederate Army general during the American Civil War. Perhaps the most highly regarded cavalry and partisan (guerrilla) leader in the war, Forrest is regarded by many military historians as that conflict's most innovative and successful general. During the course of the American Civil War he quickly transcended the ranks from private to general in response to his natural military fortitude in battle and brillant leadership abilities among comrades. His tactics of mobile warfare are still studied by modern soldiers. Forrest epitomizes the self-made man in terms of both his civilian pursuits and his military feats. Directly preceding the war's onset, Forrest had become a successful businessman and successfully lifted his family out of poverty. Forrest is also one of the war's most controversial figures. Although he was accused of war crimes at the Battle of Fort Pillow for having led Confederate soldiers in an alleged massacre of unarmed black Union troops, the accusation was later rejected by an 1871 Congressional investigation.

After the war he was alleged to have participated in the founding of the Ku Klux Klan. Despite rumors that he was the first Grand Wizard of the Klan, the Congressional investigation of the Klan in 1871, which included several former Confederate generals, undertaken by Radical Republicans concluded that Forrest did not found the Klan, was not its leader, did not participate in its activities and worked to have it disbanded.[1]

Early life

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born in a primitive log cabin to a poor family in Chapel Hill, Tennessee. At the time, the area was referred to as Duck River country.[2] People living in the area had no modern means of manufacture and created everything by hand. Few acquired any skills beyong the basics for writing, reading, and performing simple math. Forrest was descendent of Shadrack Forest, a wealthy farmer and slave owner from Virginia who moved first to North Carolina around 1730 and later relocated again to Tennessee 76 years later in 1806 with his second son, Nathan. In the next few generations this branch of the family would lose its wealth and essentially become pioneers. Nathan was married to a Miss Baugh whose family had settled in North Carolina after initially entering the United States from Ireland.[3] Their eldest son William, born around 1798, was the father of Lieut-Gen. N.B. Forrest. William was twenty-one when his eldest son was born. Forrest was the first of blacksmith William Forrest's twelve children with Miriam "Maddie" Beck. His mother's ancestors were Scotch-Irish. Her family had resided in South Carolina before relocating to Caney Springs in Bedford County, Tennessee sometime preceeding the Forrest family's migration. They held a considerable amount of property here. Forrest's mother is reputed to have been a strict disiplinarian with her children, once alledgedly taking the switch to one of her a son said to be 18 at the time and an elisted Confederate soldier! Miriam Beck was remarried sometime after William's death to Joseph Luxton with whom she went on to have four additional children. Forrest's first and middle names seem to have been derived from those of his grandfather and the county in which he was born. Forrest had a twin sister named Fanny who would die young of typhoid fever.[4]

In his youth Forrest demonstrated courage and leadership at a young age, killing a rattlesnake with a stick during a berry-gathering trip with some other youngsters who failed to aid the stick-wielding youth in any way. At 13, Forrest and his family relocated to Tippah County(present-day Benton County) in northern Mississippi. After his father's death, Forrest became the head of the family at the age of 16, and, through hard work and determination, was able to pull himself and his family up from poverty. He thus became a leader at a young age, taking control over his younger siblings and effectively organizing the household. Two brothers and all three of his sisters would die from typhoid as children leaving behind Forrest and six younger brothers, the youngest born after William's death.[5]

On the farm his father had worked Forrest would continue the tradition of raising crops and eventually accrued a consideratble amount of livestock. He often worked tirelessly for long hours to see to a successful yield and quickly developed a close familial bond with his brothers. In three years he had provided the family with a very comfortable standard of living.[6]

In February 1841, Forrest had ensured his family with enough prosperity that he decided to jourey to Texas where attempts to create the Lone Star Republic were being made. A group of volunteers amassed to come to the assistance of the Texans in a time when Americans were enraptured by the struggle taking place there. Forrest traveled to Houston where he was told that their assistance was not needed and they were instructed to return to their homes. Forrest struggled to earn enough money as a temporary farm hand until he had sufficient funds to return to Mississippi.[7]

In 1842 (age 21), he went into business with his uncle in Hernando, Mississippi as a cattle and horse trader. His uncle, Jonathan, had earned respect in his profession and Forrest was eager to have the oppurtunity to work with him. Soon he was offered a partnership. In 1845 his uncle was killed there during a dispute with four farmers known as the Matlock brothers, but, after himself being shot and only minorly wounded, Forrest shot and killed two of them with his two shot pistol and wounded the two others with a Bowie knife someone threw to him durring the scuffle. Ironically, one of the wounded men survived and served under Forrest during the Civil War. Forrest continued with the business until 1851. [8]

Forrest was to become a businessman, an owner of several plantations and a slave trader based on Adams Street in Memphis. In 1858 Forrest (a registered Democrat) was elected as a Memphis city alderman.[9] Forrest provided financially for his mother, put his younger brothers through college, and, by the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, he had become a millionaire and one of the richest men in the American South.

Civil War

Forrest earned much of his fortune engaging in the slave trade (as much as $5,000 per year). Like a majority of Southerners Forrest supported secession for the several causes of taxation levied against the South to support Northern industrialization, states' rights and slavery and supported the Confederate (CSA) side in the war.

After war broke out, Forrest returned to Tennessee and enlisted as a private in the Confederate States Army. On July 14, 1861, he joined Captain J.S. White's Company "Q", Tennessee Mounted Rifles.[10] Upon seeing how badly equipped the CSA was, Forrest made an offer to buy horses and equipment for a regiment of Tennessee volunteer soldiers with his own money.

His superior officers and the state governor, surprised that someone of Forrest's wealth and prominence had enlisted as a soldier of the lowest rank, commissioned him as a colonel. In October of 1861 he was given command of his own regiment, "Forrest's Tennessee Cavalry Battalion". Forrest had no prior formalized military training or experience. He applied himself diligently to learn, and having an innate sense of successful tactics and strong leadership abilities, Forrest soon became an exemplary soldier. He also commanded all-black Confederate units. In Tennessee, there was much public debate concerning the state's decision to join the Confederacy, and both the CSA and the Union armies were actively seeking Tennessean recruits.[11] Forrest sought men eager for battle, promising them that they would have "ample opportunity to kill Yankees."

Forrest was also physically imposing—six-foot, two-inches tall (1.88 m), 210 pounds (95 kg) —very large for the day, and as such could be very intimidating. He also used to great effect his skills as a hard rider and fierce swordsman. (He was known to sharpen both the top and bottom edges of his heavy saber.)

It has been surmised from contemporaneous records that Forrest may have personally killed more than thirty men with saber, pistol and shotgun.

Cavalry command

Forrest first distinguished himself at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862, where his cavalry captured a Union artillery battery and then had to break out of a Union Army siege headed by Ulysses S. Grant. During a meeting with superiors, Forrest found them intransigently opposed to his idea of getting his soldiers out of the fort across the Cumberland River. Forrest angrily walked out, declaring that he had not led his men into battle to surrender. He proved his point when he rallied nearly 4,000 troops and led them across the river, sparing their lives so they could fight again. A few days later, with the fall of Nashville imminent, Forrest took command of the city, which was the home for millions of dollars in heavy machinery used to make Confederate weapons. He had the machinery and several important government officials hastily transported out.

A month later, Forrest was back in action at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6 to April 7, 1862). Once again he found himself in command of the Confederate rear guard after a lost battle, and again he distinguished himself. Late in the battle, in an incident itself called Fallen Timbers, he charged and drove through the Union skirmish line. Finding himself in the midst of the enemy without any of his own troops around him, he first emptied his pistols and then pulled out his saber. A union infantryman on the ground beside him fired at Forrest, hitting him in the side with a rifle shot that lifted him out of his saddle. The ball went through his pelvis and lodged near his spine. Steadying himself and his mount, he used one arm to lift the Union soldier by the shirt collar and then wielded him as a human shield before casting his body aside. Forrest is acknowledged to have been the last man wounded at the Battle of Shiloh.

Forrest recovered from the injury soon enough to be back in the saddle by early summer to command a new brigade of green cavalry regiments. In July, he led them back into middle Tennessee after receiving an order from the commanding general, Braxton Bragg, to launch a cavalry raid. It proved another stunning success. On Forrest's birthday, July 13, 1862, his men descended on the Union-held city of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and, in the First Battle of Murfreesboro, defeated and captured a force of twice their number.

The raid into Murfreesboro, which was undertaken to rescue civilians taken hostage and scheduled to be executed in retaliation for Union military casualties, included some of the armed Black Southerners who rode with Forrest. This was documented in the official report of the Union commander:

"The forces attacking my camp were the First Regiment Texas Rangers [8th Texas Cavalry, Terry's Texas Rangers, ed.], Colonel Wharton, and a battalion of the First Georgia Rangers, Colonel Morrison, and a large number of citizens of Rutherford County, many of whom had recently taken the oath of allegiance to the United States Government. There were also quite a number of negroes attached to the Texas and Georgia troops, who were armed and equipped, and took part in the several engagements with my forces during the day." - Federal Official Records, Series I, Vol XVI Part I, pg. 805, Lt. Col. Parkhurst's Report (Ninth Michigan Infantry) on General Forrest's attack at Murfreesboro, Tenn, July 13, 1862

Murfreesboro proved to be just the first of many victories Forrest would win; he remained undefeated in battle until the final days of the war, when he faced overwhelming numbers. But he and Bragg could not get along, and the Confederate high command did not realize the degree of Forrest's talent until far too late in the war. In their postwar writings, both Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee lamented this oversight.

Forrest's early successes gained a promotion (July) to brigadier general, and he was given command of a Confederate cavalry brigade. In battle, he was quick to take the offensive, using speedy deployment of horse cavalry to position his troops, where they would often dismount and fight. He usually sought to circle the enemy flank and cut off their rear guard support. These tactics foreshadowed the mechanized infantry tactics used in World War II and had little relationship to the formal cavalry traditions of reconnaissance, screening, and mounted assaults with sabers.

Mobile cavalry warfare

In December 1862, Forrest's veteran troopers were reassigned by Bragg to another officer, against his protest, and he was forced to recruit a new brigade, this one composed of about 2,000 inexperienced recruits, most of whom lacked even weapons with which to fight. Again, Bragg ordered a raid, this one into west Tennessee to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under General Grant, threatening the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Forrest protested that to send these untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders. On the ensuing raid, he again showed his brilliance, leading thousands of Union soldiers in west Tennessee on a "wild goose chase" trying to locate his fast-moving forces. Forrest never stayed in one place long enough to be located, raided as far north as the banks of the Ohio River in southwest Kentucky, and came back to his base in Mississippi with more men than he had started with, and all of them fully armed with captured Union weapons. As a result, Grant was forced to revise and delay the strategy of his Vicksburg Campaign significantly.

Forrest continued to lead his men in smaller-scale operations until April of 1863, when the Confederate army dispatched him into the backcountry of northern Alabama and west Georgia to deal with an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen under the command of Col. Abel Streight. Streight had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of Chattanooga, Tennessee, which would have cut off Bragg's supply line and forced him to retreat into Georgia. Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days, harassing them all the way, until Streight's lone objective became simply to escape his relentless pursuer. Finally, on May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight at Rome, Georgia, and took 1,700 prisoners.

Forrest served with the main army at the Battle of Chickamauga (September 18 to September 20 1863), where he pursued the retreating Union army and took hundreds of prisoners. Like several others under Bragg's command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. Bragg failed to do so, and not long after, Forrest and Bragg had a confrontation (including death threats against Bragg) that resulted in Forrest's re-assignment to an independent command in Mississippi.

Brice's Crossroad

The battle at Brice's Crossroads is favored as one of Forrests' greatest accomplishments. Forrest set up a position for an attack to repulse a pursuing force commanded by General Samuel D Sturgis. Sturgis had been sent specifically to impede Forrest from destroying Union supplies and fortifications. When Sturgis' Federal army came upon the crossroad they were ambushed by Forrest's elite cavalry. In a desperate movement, Sturgis ordered his infantry to advance to the front line to counteract the cavalry. The infantry, tired and weary from the march to the front, were quickly broken and sent into mass retreat. Forrest, seizing the opportunity, sent a full charge after the retreating army and thus caused one of most embarrassing and costly retreats for the Union side, capturing 16 artillery pieces, 176 wagons and 1,500 stands of small arms. In all, the maneuver had cost Forrest 96 men killed and 396 wounded, however the day was far worse for his enemy with 223 killed, 394 wounded and 1,623 men missing. This had been an especially deep blow to the black regiment under Sturgis' command, who had in the hasty retreat, striped off commemorative badges that read "Remember Fort Pillow" to hold from further aggravating the Confederate force pursuing them.

Battle of Fort Pillow

Forrest went to work and soon raised a 6,000-man force of his own, which he led back into west Tennessee. He did not have the resources to retake the area and hold it, but he did have enough force to render it useless to the Union army. He led several more raids into the area, from Paducah, Kentucky, on March 25 1864, to the controversial Battle of Fort Pillow on April 12 1864. In that battle, Forrest demanded unconditional surrender, or else he would "put every man to the sword", language he frequently used to expedite a surrender. The battle's details remain disputed and controversial to this day. What is known is that Forrest's men stormed the lightly guarded fort, inflicting heavy casualties on its defenders who quickly fell into disarray as the Union command—already short several officers—collapsed.

Union commanders at Ft. Pillow had sheltered the white troops in "bombproofs" - dugout pits shielded with heavy timbers and earth - while placing the Colored Troops on the walls where they would bear the brunt of the assault and casualties. Only when the Colored Troops had been overrun and the fighting fell to white Union troops did the Union forces break and stream to the riverbanks and the support of Union river gunboats.

Conflicting reports of what happened next are the source of controversy. Some alleged that the Confederates targeted several hundred African-American soldiers inside the fort, though one battle account says the killing was indiscriminate and another said that the deaths were directly ordered by Gen. Forrest. Only 90 out of approximately 262 blacks survived the battle. Casualties were also high among white defenders of the fort, with 205 out of about 500 surviving. After the battle, reports surfaced of captured soldiers being subjected to brutality, including allegations that they were crucified on tent frames and burnt alive.

Forrest's men were alleged to have set fire to Union barracks with wounded Union soldiers inside, but the report of Union LT Daniel Van Horn (Numbers 16. Report of Lieutenant Daniel Van Horn, Sixth U. S. Colored Heavy Artillery, of the capture of Fort Pillow - Federal Official Records, Series I, Vol. 32, Part 1, 569-570) credited that act to orders carried out by Union LT John D. Hill.

LT Van Horn also reported that, "There never was a surrender of the fort, both officers and men declaring they never would surrender or ask for quarter."

Following the cessation of hostilities Forrest transferred the 14 most seriously wounded United States Colored Troops (USCT) to the U.S. Steamer Silver Cloud. He also forwarded 39 USCT taken as prisoners to higher command.

An investigation by Union general William T. Sherman did not find any fault with Forrest.

Conclusion of the war

Forrest's greatest victory came on June 10 1864, when his 3,500-man force clashed with 8,500 men commanded by General Samuel D. Sturgis at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads. Here, his mobility of force and superior tactics won a remarkable victory, inflicting 2,500 casualties against a loss of 492, and sweeping the Union forces completely from a large expanse of southwest Tennessee and northern Mississippi.

Forrest led other raids that summer and fall, including a famous one into Union-held downtown Memphis in August 1864 (the Second Battle of Memphis), and another on a huge Union supply depot at Johnsonville, Tennessee, on October 3 1864, causing millions of dollars in damage. In December, he fought alongside the Confederate Army of Tennessee in the disastrous Franklin-Nashville Campaign. He once again fought bitterly with his superior officer, demanding permission from John Bell Hood to cross the river at Franklin and cut off John M. Schofield's Union army's escape route. After the bloody defeat at Franklin, Hood continued to Nashville while Forrest led an independent raid against the Murfreesboro garrison. Forrest engaged Union forces near Murfreesboro on December 5, 1864 and was soundly defeated at what would be known as the Battle of the Cedars. After Hood's Army of Tennessee was all but destroyed at the Battle of Nashville, Forrest again distinguished himself by commanding the Confederate rear-guard in a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape from the disastrous Battle of Nashville. For this, he earned promotion to the rank of lieutenant general.

In 1865, Forrest attempted, without success, to defend the state of Alabama against the destructive Wilson's Raid. His opponent, Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, was one of the few Union generals ever to defeat Forrest in battle. He still had an army in the field in April, when news of Lee's surrender reached him. He was urged to flee to Mexico, but chose to share the fate of his men, and surrendered. On May 9 1865, at Gainesville Forrest read his farewell address to his troops.[12] He was later cleared of any violations of the rules of war in regard to the alleged massacre at Fort Pillow, and was allowed to return to private life.

In the four years of the war, reputedly a total of 30 horses were shot out from under Forrest and he may have personally killed 31 people. "I was a horse ahead at the end," he said.

Lieutenent General N.B. Forrest's Farewell Address To His Troops, May 9, 1865

The following text is excerpted from General Forrest's farewell address to Forrest's Cavalry Corps made May 9, 1865 at headquarters in Gainesville, Alabama. It is a particularly sobering prelude to the experiences the South had during Reconstruction.

Civil war, such as you have just passed through naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. It is our duty to divest ourselves of all such feelings; and as far as it is in our power to do so, to cultivate friendly feelings towards those with whom we have so long contended, and heretofore so widely, but honestly, differed. Neighborhood feuds, personal animosities, and private differences should be blotted out; and, when you return home, a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure the respect of your enemies. Whatever your responsibilities may be to Government, to society, or to individuals meet them like men.

The attempt made to establish a separate and independent Confederation has failed; but the consciousness of having done your duty faithfully, and to the end, will, in some measure, repay for the hardships you have undergone. In bidding you farewell, rest assured that you carry with you my best wishes for your future welfare and happiness. Without, in any way, referring to the merits of the Cause in which we have been engaged, your courage and determination, as exhibited on many hard-fought fields, has elicited the respect and admiration of friend and foe. And I now cheerfully and gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the officers and men of my command whose zeal, fidelity and unflinching bravery have been the great source of my past success in arms.

I have never, on the field of battle, sent you where I was unwilling to go myself; nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers, you can be good citizens. Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the Government to which you have surrendered can afford to be, and will be, magnanimous.

War record and promotions

- Enlisted as private July 1861. (Company "E", Tennessee Mounted Rifles)

- Commissioned Lt. Colonel October 1861. (Raised 7th Tennessee Cavalry)

- Promoted, Colonel February 1862, Battle of Fort Donelson.

- Wounded, Battle of Shiloh, April 1862.

- Promoted, Brig. General July 21, 1862, 3rd Tennessee Cavalry.

- First Battle of Murfreesboro, July 1862.

- Raids in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi, Fall 1862 – Spring 1863.

- Battle of Day's Gap, April – May 1863.

- Battle of Chickamauga, September 1863.

- Promoted, Major General, December 4, 1863.

- Battle of Paducah, March 1864.

- Battle of Fort Pillow, April 1864.

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads, June 1864.

- Raids in Tennessee, August – October 1864.

- Battle of Spring Hill, November 1864.

- Battle of Franklin, November 1864.

- Battle of Nashville, December 1864.

- Promoted, Lt. General, February 28, 1865.

- Final Address to his troops, May 1865.

Impact of Forrest's doctrines

Forrest was one of the first men to grasp the doctrines of "mobile warfare" that became prevalent in the 20th century. Paramount in his strategy was fast movement, even if it meant pushing his horses at a killing pace, which he did more than once. Noted Civil War scholar Bruce Catton writes:

Forrest ... used his horsemen as a modern general would use motorized infantry. He liked horses because he liked fast movement, and his mounted men could get from here to there much faster than any infantry could; but when they reached the field they usually tied their horses to trees and fought on foot, and they were as good as the very best infantry. Not for nothing did Forrest say the essence of strategy was "to git thar fust with the most men."[13]

Forrest is often erroneously quoted as saying his strategy was to "git thar fustest with the mostest," but this quote first appeared in print in a New York Times story in 1917, written to provide colorful comments in reaction to European interest in Civil War generals. Bruce Catton writes, "Do not, under any circumstances whatever, quote Forrest as saying 'fustest' and 'mostest.' He did not say it that way, and nobody who knows anything about him imagines that he did." [14]

Forrest became well-known for his early use of "guerrilla" tactics as applied to a mobile horse cavalry deployment. He sought to constantly harass the enemy in fast-moving raids, and to disrupt supply trains and enemy communications by destroying railroad track and cutting telegraph lines, as he wheeled around the Union Army's flank. His success in doing so is reported to have driven Ulysses S. Grant to fits of anger.

Many students of warfare have come to appreciate Forrest's somewhat novel approach to cavalry deployment and quick hit-and-run tactics, both of which have influenced mobile tactics in the modern mechanized era. A report on the Battle of Paducah stated that Forrest led a mounted cavalry of 2,500 troopers 100 miles in only 50 hours.

One of Forrest's most famous quotes is "War means fightin', and fightin' means killin'."

Postwar years and Ku Klux Klan

- For more details on this topic, see Ku Klux Klan.

After the war, Forrest settled in Memphis, Tennessee, building a house on a bank of the Mississippi River. With slavery abolished, the former slave trader suffered a major financial setback. He later found employment at the Selma-based Marion & Memphis Railroad and eventually became the company president. He was not as successful in railroad promoting as in war, and under his direction the company went bankrupt.

It was during this time that he became the nexus of the nascent Ku Klux Klan movement. Upon learning of the Klan and its goals of removing Northerners and reinstating the "true" Southern leaders, Forrest remarked, "That's a good thing; that's a damn good thing. We can use that to keep the niggers in their place."[7] Delegates at an 1867 KKK convention in Nashville acclaimed him and named him the organization's honorary first Grand Wizard, or leader-in-chief. There has been no proof that Forrest willingly participated or accepted this acclamation or that he actually functioned as a member of the Klan at any level.

In an 1868 newspaper interview, Forrest boasted that the Klan was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men, and that although he himself was not a member, he was "in sympathy" and would "cooperate" with them, and could himself muster 40,000 Klansmen with only five days' notice in reference to what some at the time saw as an impending conflict between the Unionist Reconstruction militia controlling voting and the civilian population. He stated that the Klan did not see its enemy as blacks so much as "carpetbaggers" (Northerners who came south after the war ended) and "scalawags" (white Republican Southerners).

In the interview Forrest described the Klan as "a protective political military organization...The members are sworn to recognize the government of the United States...Its objects originally were protection against Loyal Leagues and the Grand Army of the Republic..."

He also stated that "There were some foolish young men who put masks on their faces and rode over the country, frightening negroes, but orders have been issued to stop that, and it has ceased."

Because of Forrest's prominence, the organization grew rapidly through making use of his name. The primary original mission of the Klan was to counter with force the terror tactics being used by groups in Tennessee such as the Union League which were directed by Unionist Tennesseeans against former Confederates and secessionist Tennesseeans under the blanket abuses of state Reconstructionist governments. In addition to aiding Confederate widows and orphans of the war, some members of the new group began to use force to prevent blacks from voting and to resist Reconstruction.

In 1869, Forrest, disagreeing with its increasingly violent tactics and specifically disagreeing with violent acts against Blacks, ordered the Klan to disband, stating that it was "being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace." Many of its groups in other parts of the country ignored the order and continued to function.

When Forrest testified before a Congressional investigation in 1871 ("The reports of Committees, House of Representatives, second session, forty-second congress," 7-449) the committee concluded that Forrest's involvement with the Klan was to attempt to order it to disband. They found no evidence that he had founded the Klan, that he had led the Klan or that he had acted to advise it other than to make efforts to have it disband.

Nearly ruined as the result of the failure of the Marion & Memphis Railroad in the early 1870s, Forrest spent his final days running a prison work farm on President's Island in the Mississippi River, his health in steady decline. He and his wife lived in a log cabin they had salvaged from his plantation.

On July 5, 1875, Forrest became the first white man to speak to the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers Association, a civil rights group whose members were former slaves. Although his speech was short, he expressed the opinion that blacks had the right to vote for any candidates they wanted and that the role of blacks should be elevated. He ended the speech by kissing the cheek of one of the daughters of one of the Pole-Bearer members.[1][2]

Forrest died in October 1877, reportedly from acute complications of diabetes, in Memphis and was buried at Elmwood Cemetery. In 1904 his remains were disinterred and moved to Forrest Park, a Memphis city park.

Posthumous legacy

The only soldier on either side to go from private to general officer during the war. Propaganda controversy still surrounds his actions at Fort Pillow perpetuated by those who ignore the facts of the incident, and his reputation has been marred by disproven allegations regarding his supposed leadership role in the first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan. His remarkably changed views on race in his later years were quickly forgotten as Forrest erroneously became an icon for the Klan and holdout racist Southerners who mistakenly believed Forrest to have been a scion of racism and segregation. [citation needed]

Regardless, Forrest will always be considered a military leader of great native skill who advanced principles of wartime cavalry deployment and mobile strike capability that continue to be relevant to the philosophy and tactics of modern mobile warfare.

For many Tennesseans, Forrest remains a hero, a sentiment reflected in numerous memorials. Obelisks in his memory have been placed at his birthplace in Chapel Hill and at Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park near Camden. A statue of Forrest as a general stands in Memphis's Nathan Bedford Forrest Park, while a bust of him sculpted by Jane Baxendale is on display at the state capitol building in Nashville. He is also the namesake of Camp Forrest, a World War II Army base in Tullahoma, Tennessee that is now the site of the Arnold Engineering Development Center. Perhaps most interesting is the spot just off Interstate 65 south of Nashville where a massive but strange statue of Forrest on horseback continues to stand. Here his face takes on a comical growl, and his oversized silver body sits atop an undersized bronze mount. Both detractors and admirers of Forrest dislike this rendering with such intensity that in 2002 someone finally shot at it. Tennessee has also dedicated thirty-two Nathan Bedford Forrest state historical markers. Even though the state claims three Presidents of the United States of America as its own—Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson—Forrest has more markers and monuments in his honor than these three presidents combined. [citation needed]

Standing next to an earlier monument to Confederate soldiers buried there, a monument to Forrest in the Old Live Oak Cemetery in Selma, Alabama reads "Defender of Selma, Wizard of the Saddle, Untutored Genius, The first with the most. This monument stands as testament of our perpetual devotion and respect for Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. CSA 1821-1877, one of the south's finest heroes. In honor of Gen. Forrest's unwavering defense of Selma, the great state of Alabama, and the Confederacy, this memorial is dedicated. DEO VINDICE." Selma was the armory for the Confederacy, providing most of the South's ammunition.

There are also high schools named for Forrest in Chapel Hill, Tennessee, and Jacksonville, Florida. However, in the latter case, the Duval County School Board is controversially looking at renaming Forrest High School in Jacksonville for any of a number of people, including Eartha White.

The Duval County School Board is hardly alone: recent years have seen attempts by black leaders in some localities to remove or eliminate Forrest monuments, usually without success. In 2005, Shelby County Commissioner Walter Bailey started an effort to move the statue over Forrest's grave and rename Forrest Park. Memphis Mayor Willie Herenton, who is black, blocked the move. Others have tried to get a bust of Forrest in the Tennessee House of Representatives chamber removed.[15]

At Middle Tennessee State University, the ROTC building is named after Forrest. The building's name has thus been the source of controversy.

Forrest's great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III, also pursued a military career, eventually attaining the rank of brigadier general in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. In 1943, N. B. Forrest III was killed in action while participating in a bombing raid over Germany.

In the 1994 motion picture Forrest Gump, the eponymous Tom Hanks character states that he was named after his ancestor General Nathan Bedford Forrest, and there is a blatantly fantasy photo montage showing the general, also played by Hanks, in military uniform and Ku Klux Klan robes - a Hollywood fantasy because no image has ever been found associating Forrest with the Klan.

In the alternative history/science fiction novel The Guns of the South by Harry Turtledove, Forrest runs for president of the Confederacy in its 1867 election but loses to Robert E. Lee.

See also

- Cavalry in the American Civil War

- Forrest City, Arkansas

- Forrest County, Mississippi

- Emma Sansom

Notes

- ↑ http://dnj.midsouthnews.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20061210/OPINION02/612100307/1014 History tells real story of Forrest

- ↑ Jack Hurst, Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1993), 115.

- ↑ John A. Wyeth, That Devil Forest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forest (New York: Harper & Brothers Pub., 1959), 2.

- ↑ John Wyeth, 1-12.

- ↑ Jack Hurst, 19-22.

- ↑ John Wyeth, 13-14.

- ↑ Jack Hurst, 22-23.

- ↑ Confederate silver dollar site.

- ↑ Domestic slave trade site.

- ↑ Tennesseans in the Civil War

- ↑ Blueshoe Nashville Travel Guide.

- ↑ Bill Slater website

- ↑ Bruce Catton, Civil War, (New York: American Heritage Press, 1971), 160.

- ↑ Bruce Catton, 160-161.

- ↑ Scott Barker, "Nathan Forrest: Still confounding, controversial," Knoxville News Sentinel, February 19, 2006.

Further reading

- Bearss, Edwin C Forrest at Brice's Cross Roads and in north Mississippi in 1864Dayton OH, Press of Morningside Bookshop, 1979

- Bearss, Ed, Unpublished remarks to Gettysburg College Civil War Institute, July 1, 2005.

- Carney, Court, "The Contested Image of Nathan Bedford Forrest", Journal of Southern History. Volume: 67. Issue: 3., 2001, pp 601+.

- Harcourt, Edward John, "Who Were the Pale Faces? New Perspectives on the Tennessee Ku Klux", Civil War History. Volume: 51. Issue: 1, 2005, pp: 23+.

- Henry, Robert Selph, First with the Most, 1944.

- Lytle, Andrew Nelson,"Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company" 1931. Republished in 1984 by J.S. Sanders & Co.

- Tap, Bruce, "'These Devils are Not Fit to Live on God's Earth': War Crimes and the Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1864-1865," Civil War History, XLII (June 1996), 116-32. on Ft Pillow.

- Williams, Edward F. "Fustest with the mostest; the military career of Tennessee's greatest Confederate, Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest Memphis", Distributed by Southern Books 1969

- Wills, Brian Steel, A Battle from the Start: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest, 1992.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Catton, Bruce, 1971. The Civil War. New York: American Heritage Press. Library of Congress Number: 77-119671

- Hurst, Jack, 1994. Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Wyeth, John Allen, [1899] 1959. That Devil Forrest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forest. New York: Harper & Brothers Pub.

External links

- Interview with Nathan Bedford Forrest ca. 1868 in Wikisource

- General Forrest Obituary, "Death of Gen. Forrest", New York Times, October 30, 1877

- Forrest's ties to KKK a trumped-up myth

- Petition calling for repair of the General Nathan Bedford Memorial Mace

- Forrest Biography (early years and wartime service)

- Interview With General N.B. Forrest

- The General Nathan Bedford Forrest Memorial at the University of the South

- Forrest's speech to the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers

- General Nathan Bedford Forrest - the first true civil rights leader

- Biography at FamousAmericans.net

- Forrest Hall Under Attack

- Online biography

- Description of Fort Pillow massacre

- Description of the Battle of Paducah

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.