Difference between revisions of "Moses de Leon" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

m |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==The Zohar== | ==The Zohar== | ||

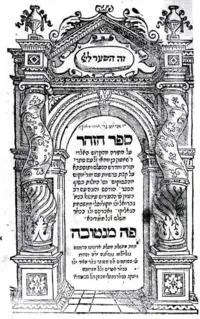

| − | [[Image:Zohar.png|thumb| | + | [[Image:Zohar.png|thumb|200px|Title page of first edition of the Zohar, Mantua, 1558. [[Library of Congress]].]] |

Toward the end of the thirteenth century, Moses de Leon wrote or compiled a kabbalistic [[midrash]] (commentary) on the [[Pentateuch]] full of esoteric [[mysticism|mystic]] [[allegories]] and rabbinical legends. This work he ascribed it to [[Simeon bar Yohai]], the great saint of the [[Tannaim]] (the early rabbinical sages of the [[Mishnah]]). | Toward the end of the thirteenth century, Moses de Leon wrote or compiled a kabbalistic [[midrash]] (commentary) on the [[Pentateuch]] full of esoteric [[mysticism|mystic]] [[allegories]] and rabbinical legends. This work he ascribed it to [[Simeon bar Yohai]], the great saint of the [[Tannaim]] (the early rabbinical sages of the [[Mishnah]]). | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

==Teachings== | ==Teachings== | ||

| + | [[Image:TreeOfLife.svg|thumb|Diagram of the ten [[Sefirot]], or [[emanation]]s of God]] | ||

The Zohar is based on the principle that all visible things have both an external, visible reality and an internal one, which hints at the reality of the spiritual world. Also, the universe consists of a series of emanations, though which humans can gradually ascend toward a consciousness of the Divine. | The Zohar is based on the principle that all visible things have both an external, visible reality and an internal one, which hints at the reality of the spiritual world. Also, the universe consists of a series of emanations, though which humans can gradually ascend toward a consciousness of the Divine. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 38: | ||

*knowledge through love | *knowledge through love | ||

| − | |||

Beyond the stage of "knowledge through love" is the ecstatic state known to the great mystics through their visions of the Divine. This state is entered by quieting the mind and remaining motionless, with the head between the knees, absorbed in contemplation while repeating prayers and hymns. There are seven ecstatic stages, corresponding to seven "heavenly halls," each characterized marked by a vision of a different hue. | Beyond the stage of "knowledge through love" is the ecstatic state known to the great mystics through their visions of the Divine. This state is entered by quieting the mind and remaining motionless, with the head between the knees, absorbed in contemplation while repeating prayers and hymns. There are seven ecstatic stages, corresponding to seven "heavenly halls," each characterized marked by a vision of a different hue. | ||

Revision as of 20:24, 29 September 2008

Moses de Leon (c. 1250 – 1305), known in Hebrew as Moshe ben Shem-Tov (משה בן שם-טוב די-ליאון), was a Spanish rabbi and Kabbalist who is believed to be the author or redactor of the famous mystical work known as the Zohar, the most important book of Jewish mysticism. For several centuries after its publication, this work was widely read and discussed, its influence in the Jewish community rivaled only by that of Hebrew Bible and the Talmud.

It is a matter of controversy whether the Zohar an original work by Moses of Leon, or whether he worked from ancient manuscripts and/or committed oral traditions to writing, dating back to the second century Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai.

Moses de Leon was born in Guadalajara, Spain, and his surname comes fron his father, Shem-Tov de León. Moses de Leon spent 30 years in Guadalajara and Valladolid before moving to Ávila, where he lived for the rest of his life. He left several other works, written in his own name, also on mystical themes He died at Arevalo in 1305 while returning to his home.

Over the next four centuries, the Zohar came to have an enormous impact on the Jewish community, stimulating tremendous interest in mysticism and also provoking criticism from conservative rabbis who objected to its other-worldly concerns and its appeal to what they considered to by legend and superstition. It was also popular among some Christian readers, who believed that it confirmed certain Christian doctrines such as the Trinity and the Fall of Man. Its readership diminished after the failed Messianic movement of Sabbatai Zevi, which fed off of kabbalistic fervor. It later became influential again through the re-emphasis on mystical ideas by Hasidic Judaism, and has recently found a new audience among Gentile audiences interested in the Kabbalah.

Writings in his own name

A serious student of the mystical tradition, Moses de Leon was familiar both with the philosophers of the Middle Ages and the whole literature of Jewish mysticism. He knew and used the writings of Shlomo ibn Gabirol, Yehuda ha-Levi, Maimonides, and others. His writings discplay the ability to charm his readers with brilliant and striking phrases, without necessarily expressing any well-defined thought.

He was a prolific writer and composed several biblical commentaries and kabbalistic works in quick succession. In the comprehensive Sefer ha-Rimon, written under his own name in 1287 and still extant in manuscript form, he treated from a mystical standpoint the objects and reasons for the Jewish ritual laws, dedicating the book to Levi ben Todros Abulafia. In 1290 he wrote Ha-Nefesh ha-Hakhamah, or Ha-Mishqal (published in Basel, 1608, and also frequently found in manuscript), which shows even greater kabbalistic tendencies. In this work he attacks the scholastic philosophers of religion and deals with a range of mystical subjects, including:

- the human soul as "a likeness of its heavenly prototype"

- the state of the soul after death

- the question of the soul's resurrection

- the transmigration of souls.

His Shekel ha-Kodesh (written in 1292), another book of the same kind, is dedicated to Todros ha-Levi Abulafia. In the Mishkan ha-Edut also called Sefer ha-Sodot, finished in 1293, he deals with heaven and hell, basing his view on the apocryphal Book of Enoch. Here, he also treats the subject of atonement. He also wrote a kabbalistic explanation of the first chapter of Ezekiel, a meditation on the heavenly throne/chariot of God, in the tradition of so-called Merkabah mysticism.

The Zohar

Toward the end of the thirteenth century, Moses de Leon wrote or compiled a kabbalistic midrash (commentary) on the Pentateuch full of esoteric mystic allegories and rabbinical legends. This work he ascribed it to Simeon bar Yohai, the great saint of the Tannaim (the early rabbinical sages of the Mishnah).

The work, written in peculiar Aramaic, is entitled Midrash de Rabban Shimon ben Yohai but it is much better known as the Zohar, the Book of Splendor. The book aroused considerable suspicion at the outset considering its supposed authorship. The story runs that after the death of Moses de Leon a rich man from Avila offered his widow, who had been left without considerable means, a large sum of money for the ancient text from her husband had used to compile the work. She, however, explained that her husband himself was the author of the work, which he had composed without reference to any ancient work other than the Hebrew Bible and traditional rabbinical works. She claimed to had asked him several times as to why he had put his teachings into the mouth of another. He reply was that doctrines put into the mouth of the miracle-working Simeon ben Yoḥai would be highly honored, and would also be a rich source of profit.

Despite this admission, many other continued to believe that Moses de Leon was either in possession of now-lost ancient manuscripts, that he was the recipient of ancient mystical oral traditions, or that he wrote the book under the inspiration of the spirit of Simeon ben Yohai and/or God Himself.

Teachings

The Zohar is based on the principle that all visible things have both an external, visible reality and an internal one, which hints at the reality of the spiritual world. Also, the universe consists of a series of emanations, though which humans can gradually ascend toward a consciousness of the Divine.

There are thus four stages of knowledge:

- the exterior aspect of things: "the vision through the mirror that projects an indirect light"

- the essence of things: "the vision through the mirror that projects a direct light"

- intuitive knowledge and

- knowledge through love

Beyond the stage of "knowledge through love" is the ecstatic state known to the great mystics through their visions of the Divine. This state is entered by quieting the mind and remaining motionless, with the head between the knees, absorbed in contemplation while repeating prayers and hymns. There are seven ecstatic stages, corresponding to seven "heavenly halls," each characterized marked by a vision of a different hue.

The Zohar teaches that man can be glorified and divinized. Its ethical principles are in keeping with the spirit of traditional Talmudic Judaism. It rejects the view Maimonides who stressed the development intellect over mystical spirituality.

Man's efforts toward moral perfection also influences the spiritual world of the divine emanations or Sefirot. The practice of virtue increases the outpouring of divine grace.

Legacy

Through the Zohar, Moses de Leon left a powerful legacy on both Jewish and Christian tradition.

The Zohar was praised by numerous rabbis for its opposition religious formalism. It stimulated the imagination and emotions, reinvigorating the spirituality of many Jews who felt suffocated by Talmudic scholasticism and legalism. Other rabbis, however were distub bed by the Zohar's propagated what they considered to be superstition and even magic. It appeal to the goal of mystical ecstasy produced generations of dreamers, whose spiritual imaginations looked at the as being populated by spirits, demons, and various other spiritual influences rather than looking the practical needs of the here and now.

The Zohar influence later kabbalists Isaac Luria and others, whose works stimulated a wave of interest Jewish mysticism throughout Europe and the Ottoman empire. Elements of the Zohar entered the Jewish liturgy of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the language of many Jewish poets of the era ideas and expressions from the Zohar may also been found. Kabbalistic fervor, much of it based on the Zohar, reached its zenith in the widespread but ultimately failed Messianic movement of Sabbatai Zevi in the mid seventeenth century, resulting in backlash of conservative rabbinism against mysticism in general. Interest in the Kabbalah in general and the Zohar in particular was revived through the work of the Baal Shem Tov and his brand of Hasidic Judaism. Today, the Zohar is once again a widely read work, although it is still looked on with some suspicion by non-Hasidic rabbis.

The enthusiasm felt for the Zohar was shared by many Christian scholars, such as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Johann Reuchlin, Aegidius of Viterbo, and others, all of whom believed that the book contained proofs of the truth of Christianity. This belief was based in part by such expression in the Zohar as "The Ancient of Days has three heads. He reveals himself in three archetypes, all three forming but one."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Caplan, Samuel. The Great Jewish Books and Their Influence on History. New York: Horizon Press, 1952. OCLC377296

- Giller, Pinchas. Reading the Zohar: The Sacred Text of the Kabbalah. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780195118490

- Marǵolies, Morris B. Twenty/Twenty: Jewish Visionaries Through Two Thousand Years. Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson, 2000. ISBN 9780765760579

- Matt, Daniel Chanan. The Zohar. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780804752107

- Moshe ben Shem Tov, and Elliot Reuben Wolfson. The Book of the Pomegranate: Moses De Leon's Sefer Ha-Rimmon. Atlanta, Ga: Scholars Press, 1988. OCLC 233680647

This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.