Difference between revisions of "Mikhail Bulgakov" - New World Encyclopedia

(Bulgakov article) |

(Bulgakov article) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

== Biography == | == Biography == | ||

| − | Mikhail Bulgakov was born in [[Kiev]], [[Ukraine]], the oldest son of a professor at | + | Mikhail Bulgakov was born in [[Kiev]], [[Ukraine]], the oldest son of a professor at Kiev Theological Academy. In [[1913]] Bulgakov married Tatiana Lappa. In [[1916]], he graduated from the Medical School of [[Kiev University]]. The Bulgakov sons enlisted in the [[White Army]] during the [[Russian Civil War|Civil War]]. All but Mikhail would up in [[Paris]] at the war's conclusion. Mikhail graduated from Kiev Univesity with a degree in medicine, enlisting as a field doctor. He ended up in the [[Caucasus]], where he eventually began working as a journalist. In [[1921]], he moved with Tatiana to [[Moscow]] where he stayed for the rest of his life. Three years later, divorced from his first wife, he married Lyubov' Belozerskaya. In [[1932]], Bulgakov married for the third time, to Yelena Shilovskaya, and settled with her at [[Patriarch's Ponds]]. During the last decade of his life, Bulgakov continued to work on ''The Master and Margarita'', wrote plays, critical works, stories, and made several translations and dramatisations of novels. |

| − | |||

| − | Bulgakov never supported the regime, and mocked it in many of his works | + | Despite his relatively favored status under the Soviet regime of [[Joseph Stalin]], Bulgakov was prevented from either emigrating or visiting his brothers in the West. Bulgakov never supported the regime, and mocked it in many of his works, most of which were consigned to his desk drawer for several decades because they were too politically sensitive to publish. In [[1938]] he wrote a letter to Stalin requesting permission to emigrate and received a personal phone call from Stalin himself denying his request. Bulgakov died from an inherited [[kidney]] disorder in 1940 and was buried in the [[Novodevichy Cemetery]] in Moscow. |

== Early works == | == Early works == | ||

| − | During his life, Bulgakov was best known for the plays he contributed to [[Konstantin Stanislavsky]]'s [[Moscow Art | + | During his life, Bulgakov was best known for the plays he contributed to [[Konstantin Stanislavsky]]'s [[Moscow Art Theater]]. They say that [[Stalin]] was fond of the play ''[[Days of the Turbins]]'' (Дни Турбиных), which was based on Bulgakov's phantasmagoric novel ''The White Guard''. His dramatization of [[Moliere]]'s life in ''The Cabal of Hypocrites'' is still run by the [[Moscow Art Theater]]. Even after his plays were banned from the theaters, Bulgakov wrote a grotesquely funny comedy about [[Ivan the Terrible]]'s visit into [[1930s]] [[Moscow]] and several plays about the young years of [[Stalin]]. This perhaps saved his life in the year of terror [[1937]], when nearly all writers who did not support the leadership of Stalin were purged. |

| − | Bulgakov started writing prose in the early [[1920s]], when he published ''The White Guard'' and a short story collection entitled ''Notes of a Country Doctor'', both based on Bulgakov's experiences in post-revolutionary [[Ukraine]]. In the mid-1920s, he came to admire the works of [[H.G. Wells]] and wrote several stories with sci-fi elements, notably ''The Fatal Eggs'' ([[1924]]) and the ''Heart of a Dog'' ([[1925]]). | + | Bulgakov started writing prose in the early [[1920s]], when he published autobiographical works, such as ''The White Guard'' and a short story collection entitled ''Notes of a Country Doctor'', both based on Bulgakov's experiences in post-revolutionary [[Ukraine]]. In the mid-1920s, he came to admire the works of [[H.G. Wells]] and wrote several stories with sci-fi elements, notably ''The Fatal Eggs'' ([[1924]]) and the ''Heart of a Dog'' ([[1925]]). |

| − | The ''[[Fatal Eggs]]'', a short story inspired by the works of [[H.G. Wells]], tells of the events of a Professor Persikov, who in experimentation with [[egg]]s, discovers a red ray that accelerates growth in living organisms. At the time, an illness passes through the [[chicken]]s of Moscow, killing most of them and, to remedy the situation, the Soviet government puts the ray into use at a farm. Unfortunately there is a mix up in egg shipments and the Professor ends up with the [[chicken]] eggs, while the government-run farm receives a shipment of [[ostrich]]es, [[snake]]s and [[crocodile]]s that were meant to go to the Professor. The mistake is not discovered until the eggs produce giant monstrosities that wreak havoc in the suburbs of Moscow | + | The ''[[Fatal Eggs]]'', a short story inspired by the works of [[H.G. Wells]], tells of the events of a Professor Persikov, who in experimentation with [[egg]]s, discovers a red ray that accelerates growth in living organisms. At the time, an illness passes through the [[chicken]]s of Moscow, killing most of them and, to remedy the situation, the Soviet government puts the ray into use at a farm. Unfortunately there is a mix up in egg shipments and the Professor ends up with the [[chicken]] eggs, while the government-run farm receives a shipment of [[ostrich]]es, [[snake]]s and [[crocodile]]s that were meant to go to the Professor. The mistake is not discovered until the eggs produce giant monstrosities that wreak havoc in the suburbs of Moscow, killing most of the workers on the farm. The [[propaganda]] machine then turns onto Persikov, distorting his nature in the same way his "innocent" tampering created the monsters. This tale of a bungling government earned Bulgakov the reputation as a [[counter-revolutionary]]. |

| − | ''[[Heart of a Dog]]'', a story obviously based on ''[[Frankenstein]]'', features a professor who implants human [[testicle]]s and [[pituitary gland]] into a dog named Sharik. The dog then proceeds to become more and more human as time passes, | + | ''[[Heart of a Dog]]'', a story obviously based on ''[[Frankenstein]]'', features a professor who implants human [[testicle]]s and [[pituitary gland]] into a dog named Sharik. The dog then proceeds to become more and more human as time passes, but his brutish manner results in all manner of chaos. The tale is clearly a critical satire on the Soviet "new man." It was turned into a comic [[opera]] called ''The Murder of Comrade Sharik'' by [[William Bergsma]] in [[1973]]. A hugely popular screen version of the story followed in [[1988]]. |

== The Master and Margarita == | == The Master and Margarita == | ||

Revision as of 12:18, 16 November 2005

Editing Mikhail Bulgakov From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jump to: navigation, search

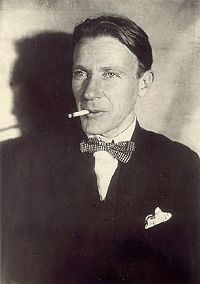

Mikhail Afanasievich Bulgakov (or Bulhakov, Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков; May 15 (May 3 Old Style), 1891 – March 10, 1940) was a Soviet novelist and playwright of the first half of the 20th century. Although a native of Kiev, he wrote in Russian. He is best known for the novel The Master and Margarita.

Biography

Mikhail Bulgakov was born in Kiev, Ukraine, the oldest son of a professor at Kiev Theological Academy. In 1913 Bulgakov married Tatiana Lappa. In 1916, he graduated from the Medical School of Kiev University. The Bulgakov sons enlisted in the White Army during the Civil War. All but Mikhail would up in Paris at the war's conclusion. Mikhail graduated from Kiev Univesity with a degree in medicine, enlisting as a field doctor. He ended up in the Caucasus, where he eventually began working as a journalist. In 1921, he moved with Tatiana to Moscow where he stayed for the rest of his life. Three years later, divorced from his first wife, he married Lyubov' Belozerskaya. In 1932, Bulgakov married for the third time, to Yelena Shilovskaya, and settled with her at Patriarch's Ponds. During the last decade of his life, Bulgakov continued to work on The Master and Margarita, wrote plays, critical works, stories, and made several translations and dramatisations of novels.

Despite his relatively favored status under the Soviet regime of Joseph Stalin, Bulgakov was prevented from either emigrating or visiting his brothers in the West. Bulgakov never supported the regime, and mocked it in many of his works, most of which were consigned to his desk drawer for several decades because they were too politically sensitive to publish. In 1938 he wrote a letter to Stalin requesting permission to emigrate and received a personal phone call from Stalin himself denying his request. Bulgakov died from an inherited kidney disorder in 1940 and was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Early works

During his life, Bulgakov was best known for the plays he contributed to Konstantin Stanislavsky's Moscow Art Theater. They say that Stalin was fond of the play Days of the Turbins (Дни Турбиных), which was based on Bulgakov's phantasmagoric novel The White Guard. His dramatization of Moliere's life in The Cabal of Hypocrites is still run by the Moscow Art Theater. Even after his plays were banned from the theaters, Bulgakov wrote a grotesquely funny comedy about Ivan the Terrible's visit into 1930s Moscow and several plays about the young years of Stalin. This perhaps saved his life in the year of terror 1937, when nearly all writers who did not support the leadership of Stalin were purged.

Bulgakov started writing prose in the early 1920s, when he published autobiographical works, such as The White Guard and a short story collection entitled Notes of a Country Doctor, both based on Bulgakov's experiences in post-revolutionary Ukraine. In the mid-1920s, he came to admire the works of H.G. Wells and wrote several stories with sci-fi elements, notably The Fatal Eggs (1924) and the Heart of a Dog (1925).

The Fatal Eggs, a short story inspired by the works of H.G. Wells, tells of the events of a Professor Persikov, who in experimentation with eggs, discovers a red ray that accelerates growth in living organisms. At the time, an illness passes through the chickens of Moscow, killing most of them and, to remedy the situation, the Soviet government puts the ray into use at a farm. Unfortunately there is a mix up in egg shipments and the Professor ends up with the chicken eggs, while the government-run farm receives a shipment of ostriches, snakes and crocodiles that were meant to go to the Professor. The mistake is not discovered until the eggs produce giant monstrosities that wreak havoc in the suburbs of Moscow, killing most of the workers on the farm. The propaganda machine then turns onto Persikov, distorting his nature in the same way his "innocent" tampering created the monsters. This tale of a bungling government earned Bulgakov the reputation as a counter-revolutionary.

Heart of a Dog, a story obviously based on Frankenstein, features a professor who implants human testicles and pituitary gland into a dog named Sharik. The dog then proceeds to become more and more human as time passes, but his brutish manner results in all manner of chaos. The tale is clearly a critical satire on the Soviet "new man." It was turned into a comic opera called The Murder of Comrade Sharik by William Bergsma in 1973. A hugely popular screen version of the story followed in 1988.

The Master and Margarita

It is the fantasy satirical novel The Master and Margarita (Мастер и Маргарита), published by his wife almost thirty years after his death, in 1967, that has granted him critical immortality. The book was available underground, as samizdat, for many years in the Soviet Union, before the serialization of a censored version in the journal Moskva. In the opinion of many, The Master and Margarita is the best of the Soviet novels, although it is difficult to imagine Joseph Stalin approving it. The novel contributed a number of sayings to the Russian language, for example, "Manuscripts don't burn". A destroyed manuscript of the Master is an important element of the plot, and in fact Bulgakov had to rewrite the novel from memory after he burned the draft manuscript with his own hands.

Famous quotes

- "Manuscripts do not burn" ("Рукописи не горят") — The Master and Margarita

- "Second-grade fresh" — The Master and Margarita

Bibliography

Short stories

- Notes on Cuffs (Записки на манжетах)

- Notes of a Country Doctor (Записки юного врача)

- Fatal Eggs (Роковые яйца)

- Heart of a Dog (Собачье сердце)

Plays

- Days of the Turbins (Дни Турбиных) — one family's survival in Kiev during the Russian Civil War

- Flight (play) (Бег) — satirizing the flight of White emigrants to the West

- Ivan Vasilievich (Иван Васильевич) — Ivan the Terrible brought by the Time Machine to a crowded apartment in the 1930s Moscow

- The Cabal of Hypocrites (Кабала святош) — Moliere's relations with Louis XIV's court

- Pushkin (The Last Days) (Пушкин) — the last days of the great Russian poet

- Batum (Батум) — Stalin's early years in Batumi

Novels

- The White Guard (Белая гвардия)

- Life of Monsieur de Molière (Жизнь господина де Мольера)

- Black Snow, or the Theatrical Novel (Театральный роман)

- The Master and Margarita (Мастер и Маргарита)

External links

- Bulgakov's Master and Margarita

- Mikhail Bulgakov

- Bulgakov.ru — amateur but very high-quality site, devoted solely to Bulgakov and his works (in Russian)

- Mikhail Bulgakov — three languages site (German, English and Russian)

- Bulgakov Project (in Russian)

bg:Михаил Булгаков de:Michail Afanasjewitsch Bulgakow et:Mihhail Bulgakov el:Μιχαήλ Μπουλγκάκοφ eo:Miĥail BULGAKOV fr:Mikhaïl Boulgakov he:מיכאיל בולגקוב lv:Mihails Bulgakovs hu:Mihail Afanaszjevics Bulgakov nl:Michail Boelgakov pl:Michaił Bułhakow ro:Mihail Bulgakov ru:Булгаков, Михаил Афанасьевич sk:Michail Bulgakov fi:Mihail Bulgakov sv:Michail Bulgakov

Edit summary:

Cancel | Editing help (opens in new window)

Insert: Á á É é Í í Ó ó Ú ú À à È è Ì ì Ò ò Ù ù  â Ê ê Î î Ô ô Û û Ä ä Ë ë Ï ï Ö ö Ü ü ß Ã ã Ñ ñ Õ õ Ç ç Ģ ģ Ķ ķ Ļ ļ Ņ ņ Ŗ ŗ Ş ş Ţ ţ Ć ć Ĺ ĺ Ń ń Ŕ ŕ Ś ś Ý ý Ź ź Đ đ Ů ů Č č Ď ď Ľ ľ Ň ň Ř ř Š š Ť ť Ž ž Ǎ ǎ Ě ě Ǐ ǐ Ǒ ǒ Ǔ ǔ Ā ā Ē ē Ī ī Ō ō Ū ū ǖ ǘ ǚ ǜ Ĉ ĉ Ĝ ĝ Ĥ ĥ Ĵ ĵ Ŝ ŝ Ŵ ŵ Ŷ ŷ Ă ă Ğ ğ Ŭ ŭ Ċ ċ Ė ė Ġ ġ İ ı Ż ż Ą ą Ę ę Į į Ų ų Ł ł Ő ő Ű ű Ŀ ŀ Ħ ħ Ð ð Þ þ Œ œ Æ æ Ø ø Å å Ə ə – — … [] [[]] {{}} ~ | ° § → ≈ ± − × ¹ ² ³ ‘ “ ’ ” £ € Α α Β β Γ γ Δ δ Ε ε Ζ ζ Η η Θ θ Ι ι Κ κ Λ λ Μ μ Ν ν Ξ ξ Ο ο Π π Ρ ρ Σ σ ς Τ τ Υ υ Φ φ Χ χ Ψ ψ Ω ω

Your changes will be visible immediately. For testing, please use the sandbox. You are encouraged to create and improve articles. The community is quick to enforce the quality standards on all articles. Please cite your sources so others can verify your work. On discussion pages, please sign your comment by typing four tildes (David Burgess 11:53, 16 November 2005 (UTC)).

DO NOT SUBMIT COPYRIGHTED WORK WITHOUT PERMISSION All edits are released under the GFDL (see WP:Copyrights). If you don't want your writing to be edited and redistributed by others, do not submit it. Only public domain resources can be copied exactly—this does not include most web pages.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mikhail_Bulgakov" ViewsArticleDiscussionEdit this pageHistory Personal toolsCreate account / log in Navigation Main PageCommunity PortalCurrent eventsRecent changesRandom articleHelpContact usDonations Search

Toolbox

What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages

This version of the article has been revised. Besides normal editing, the reason for revision may have been that this version contains factual inaccuracies, vandalism, or material not compatible with the GFDL. About Wikipedia Disclaimers

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.