Matteo Ricci

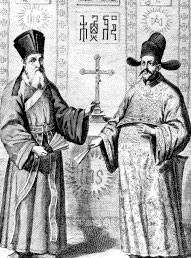

Matteo Ricci (left) and Xu Guangqi (徐光啟) (right) in the Chinese edition of Euclid's Elements (幾何原本). |

File:Matteo Ricci Far East 1602 Larger.jpg Map of the Far East by Matteo Ricci in 1602. |

Matteo Ricci (October 6 1552 - May 11 1610) (Traditional Chinese: 利瑪竇; Simplified Chinese: 利玛窦; pinyin: Lì Mǎdòu; courtesy name:西泰 Xītài) was an Italian Jesuit priest.

Early life and education

Matteo Ricci was born October 6, 1552 in Macerata, then part of the Papal States, to the noble family of Giovanni Battista Ricci, a pharmacist active in public affairs who served as governor of the city for a time, and Giovanna Angiolelli. Matteo, their oldest child, studied first at home and then entered a school that was opened in 1561 by the Jesuit priests in Macerata. He competed his classical studies, and at the age of sixteen, he went to Rome to study theology and law in a Roman Jesuits' school. There on August 15, 1571, he requested permission to join the Jesuit order. Shortly after beginning his study of science under the noted mathematician Christopher Clavius, he volunteered for work overseas in the Far East. In 1577, soon after he had begun the study of science under the mathematician Christopher Clavius, he filed an application to be a member of a Missionary to India. He went to Portugal, where he studied at the University of Coimbra while he waited for passage. On March 24, 1578, he left Lisbon, arriving on September 13 at Goa, the Portuguese colony on the central west coast of India. Here he continued his studies for the priesthood, and in 1580 he was ordained at Cochin, on the Malabar Coast, where he had been sent to recover his health. In 1582, he was dispatched to China.

Missionary Work in China

By the sixteenth century, the early Nestorian Christian communities founded in the seventh century and the Catholic missions of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries had vanished, and Christians were nonexistent in China. After the death of Francis Xavier in 1522, numerous attempts by missionaries to enter China had failed. Finally, Father Alessandro Valignano, who had received Ricci into the Jesuits and was at this time visitor of the Jesuit missions in the Far East, established a new method of evangelizing by adapting to national customs. In 1579, he sent Father Michele de Ruggieri to Macao, a Portuguese trading post in Southern China, with instructions to study the Mandarin language. In 1582, Ricci arrived in Macao to start learning the Chinese language and customs, and eventually mastered Chinese classical script. The Chinese mandarins had allowed Father Ruggieri two short visits to Canton. In 1583, Matteo Ricci, was invited to reside with Ruggieri at Zhaoqing (Chao-k'ing), the administrative capital of Canton in Guangdong (Kwangtung) Province, by the governor of Zhaoqing at the time, Wang P'an, who had heard of Ricci's skill as a mathematician and cartographer. Ruggieri returned to Italy in 1588; Ricci stayed in Zhaoqing until a new viceroy expelled him in 1589. In his History of the Introduction of Christianity in China, Ricci described their work as follows:

“So as not to occasion any suspicion about their work, the fathers [the Jesuits] initially did not attempt to speak very clearly about our holy law. In the time that remained to them after visits, they rather tried to learn the language, literature, and etiquette of the Chinese, and to win their hearts and, by the example of their good lives, to move them in a way that they could not otherwise do because of insufficiency in speech and for lack of time.

When questioned by the mandarins, the missionaries would say that “they were religious who had left their country in the distant West because of the renown of the good government of China, where they desired to remain till their death, serving god, the Lord of Heaven." However, the missionaries never hid their faith or their Christianity, and as soon as they were settled in Chao-k'ing, they put a picture of Virgin Mary and Infant Jesus in a conspicuous place where all visitors to the house could see it. Most visitors inquired about the image, and the missionaries were able to give an initial explanation of Christianity. The missionaries appealed to the curiosity of their Chinese acquaintances by making them feel that they had something new and interesting to teach, using European items like clocks, prisms, astronomical instruments, oil paintings, musical instruments, picture book and architectural drawings to attract interest. Soon their house was constantly filled with educated visitors, who "all came by degrees to have with regard to our countries, our people, and especially of our educated men, an idea vastly different from that which they had hitherto entertained". It was in Zhaoqing, in 1584, that Ricci composed the first map of the world in Chinese, the “Great Map of Ten Thousand Countries,” at the request of the Governor of Chao-k'ing, who printed copies for his friends.

There is now a memorial plaque in Zhaoqing to commemorate Ricci’s six-year stay there. In 1589, after being expelled from Zhaoqing (Chao-ch'ing), Ricci moved to Shao-chou (Shiuhing), where he taught mathematics to the Confucian scholar Ch'ü T'ai-su, receiving in exchange an introduction into the society of the mandarins and Confucian scholars. Ch'ü T'ai-su advised him to change his apparel from the habit of a Buddhist monk to that of a Chinese scholar. In 1595, Ricci reached Nan-king, with the intention of establishing himself in the Imperial city of Peking. He formed a Christian church at Nan-ch'ang, capital of Kiang-si, where he stayed from 1595 to 1598. There he befriended two princes of royal blood, and at the request of one of them, wrote his first book in Chinese, “On Friendship.” In September of 1598, he unsuccessfully tried to meet the Emperor, but a conflict with Japan in Korea had made all foreigners objects of suspicion, and he was not successful in reaching the Imperial Palace. He returned to Nanking in February of 1599, and found that the political climate had changed; he was now welcomed by the government officials. He occupied himself chiefly with astronomy and geography, finding that this made a deep impression on the Chinese scholars.

Although he was successful in Nanking, Ricci felt that the mission in China would not be secure until it was established in Peking, with official authorization. On 18 May, 1600, Ricci again set out for Peking. He was not initially granted an audience with the Emperor of China but, after he presented the Emperor with a chiming clock, Ricci was finally allowed to present himself at the Imperial court of Wan-li. He entered on January 24, 1601, accompanied by the young Jesuit, Diego Pantoja. Ricci was the first Westerner to be invited into the Forbidden City. Although he never met the Emperor, he met important officials and was given permission to remain in the capital. Ricci never left Peking for the rest of his life. His efforts to proselytize brought him into contact with Chinese intellectuals such as Li Chih-tsao, Hsü Kuang-ch'i, and Yang T'ing-yün (known as the “Three Pillars of the Early Catholic Church” in China), who assisted the missionaries with their literary efforts, and Feng Ying-ching, a scholar and civic official who was imprisoned in Peking. Ricci wrote several books in Chinese: “The Secure Treatise on God” (1603), “The Twenty-five Words” (1605), “The First Six Books of Euclid” (1607), and “The Ten Paradoxes” (1608). He composed treatises adapted to the Chinese taste, using examples, comparisons, and extracts from the Scriptures and from Christian philosophers and doctors. His "T'ien-chu-she-i" (The Secure Treatise on God) was reprinted our tiems before his death, and twice by the Chinese. This work induced Emperor K'ang-hi to issue an edict of 1692 granting Christians liberty to preach the Gospel in China. The Emperor Kien-long, who persecuted the Christians, nevertheless ordered the "T'ien-chu-she-i" to be placed in his library as part of a collection of the most notable productions of the Chinese language. Ricci’s success in China was due to his ability to understand the Chinese and to go beyond barriers of culture and language. Ricci learned to speak and write in ancient Chinese, and was known for his appreciation of the indigenous culture of the Chinese. During his early life in China, he referred to himself as a Western Monk, a term relating to Buddhism. Later, he discovered that in contrast to the cultures of South Asia, Confucian thought was dominant in the Ming dynasty and Chinese culture was strongly intertwined with Confucian values. Ricci became the first to translate the Confucian classics into a western language, Latin; in fact "Confucius" was Ricci's own Latinisation. He came to call himself a "Western Confucian" (西儒). The credibility of Confucius helped Christianity to take root.

Ricci’s disseminaton of Western knowledge about mathematics, astronomy and geometry also helped protect Christian missions in China until the end of the eighteenth century, because the Chinese government wished to profit from the missionaries.

Ricci also met a Korean emissary to China, Yi Su-gwang, to whom he taught the basic tenets of Catholicism and transmitted western knowledge. Ricci gave Yi Su-gwang several books from the West, which became the basis of Yi Su-gwang's later works. Ricci's transmission of western knowledge to Yi Su-gwang influenced and helped shape the foundation of the Silhak movement in Korea.

While advancing to Peking, Ricci trained fellow workers to continue his work in the cities he had left. By 1601, the mission included, besides Peking, three residences in Nan-king, Nan-ch'ang, Shao-chow, each with two or three Jesuit missionaries and catechists from Macao; another residence in Shang-hai was added in 1608. By 1608, two thousand Christioans had been baptized in China. Ricci lived on in China until the end of his life. Matteo Ricci died in Beijing on May 11, 1610.

Further reading

- Cronin, Vincent. 1955. The wise man from the West. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-00-626749-1

- Leys, Simon. 1986. The burning forest: essays on Chinese culture and politics. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN: 0030050634 9780030050633

- Spence, Jonathan D. 1984. The memory palace of Matteo Ricci. New York, N.Y.: Viking Penguin. ISBN: 0670468304 : 9780670468300

==See also==

- Religion in China

- List of Roman Catholic missionaries in China

- Jesuit China missions

- Christianity in China

- 19th Century Protestant Missions in China

- List of Protestant missionaries in China

External links

Works

An excerpt from On Chinese Government, Selection from his Journals by Matteo Ricci

An excerpt from The Art of Printing by Matteo Ricci

Resources

- Matteo Ricci. Catholic Encyclopedia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.