Li Chunfeng

Li Chunfeng (Traditional Chinese: 李淳風; Simplified Chinese: 李淳风; Hanyu Pinyin: Lǐ Chúnfèng; Wade-Giles: Li Ch'unfeng) (602 – 670) was a major Feng shui scholar of the Tang Dynasty, China, and a mathematician, astronomer, and historian who was born in today's Baoji, Shaanxi. He was first appointed to the Imperial Astronomy Bureau to help institute calendar reform. He eventually ascended to become deputy of the Imperial Astronomy Bureau and designed the Linde calendar.

Astronomy was important subject in ancient Chinese history not only as a scientific theory, but also as an essential part of a general theory of hermeneutics. Scholars interpreted constellations and celestial movements, which informed a framework within which events, in daily life or of historical significance, are interpreted. Astronomy was also tied to ideas of the Mandate of Heaven and Feng shui, which reached their maturity during the in Tang Dynasty. Li Chunfeng was a major theorists who contributed to the development of Feng shui theories.

Background

Li was sixteen when the Sui Dynasty fell and the Tang Dynasty rose, during which the Imperial Academy's math teaching was formalized. He was appointed as an advanced court astronomer and historian, and then was promoted to deputy of the Imperial Astronomy Bureau in 627.

Astronomy or calender-making was a very important job because of the Chinese belief that political governance is spiritually controlled and morally justified by the Mandate of Heaven. If a ruler is in discordance with the Mandate of Heaven, the ruler loses his legitimacy for he no longer has spiritual support from and moral justification by Heaven. This spiritual principle is tied to readings of celestial configurations, and astronomers studied the stars in order to inform a general theory of hermeneutics with which to interpret events. Thus, astronomers were not only scientists but also prophets, spiritual consultants, fortune tellers, and political advisers. For example Emperors determined when and how they should conduct major events in consultation with court astronomers.

Together with geography, astronomy is one of two major constitutive components of Feng shui which is rooted in ancient theories of Yin and Yang, I Ching, Qi, and others. Li Chungfeng was a major Feng shui scholar of the Tang Dynasty. During the Tang Dynasty, Feng shui reached its maturity. The theory was widely applied to all facets of life, particularly to the Imperial Examination through which the general public had the chance to become a bureaucrat. Passing the examination was a path of social success in Chinese feudalistic society and Feng shui was used to discern one's "fortune" or likelihood of passing the exam. For example, some held that a good tomb enables one to receive spiritual support from one's ancestors.[1]

Linde calendar

The Wuyin calendar, a calender used during Li Chunfeng's time, was inaccurate and could not accurately predict eclipses. Li was selected to reform the calender.

In 665, Li introduced a reform calendar called the Linde calendar. It improved the prediction of planets' positions and included an “intercalary month,” which is similar to the idea of a leap day. The Linde calendar would account for the difference between the lunar and solar year, as twelve lunar months are 1.3906 days short of one solar year. The Linde calendar is Li Chunfeng's most prominent accomplishment.

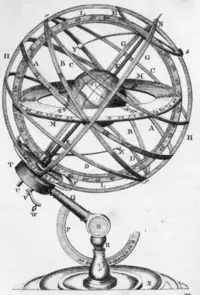

Li wrote a document criticizing the use of outdated equipment in the Imperial Astronomy Bureau, so he was commanded to construct a new armillary sphere. An "armillary sphere" (variations are known as "spherical astrolabe," "armilla," or "armil") is a model of the celestial sphere.

Throughout Chinese history, astronomers have created celestial globes (Simplified Chinese: 浑象) to assist in the observation of stars. The Chinese also used the armillary sphere in aiding calendrical computations and calculations. Chinese ideas of astronomy and astronomical instruments became known in Korea as well, where further advancements were also made.

Li Chunfeng created one in 633 C.E. with three spherical layers to calibrate multiple aspects of astronomical observations, calling them 'nests' (chhung).[2] He was also responsible for proposing a plan to have a sighting tube mounted ecliptically in order to better observation of celestial latitudes. However, it was Yi Xing in the next century who would accomplish this addition to the model of the armillary sphere.[3] Ecliptical mountings of this sort were found on the armillary instruments of Zhou Cong and Shu Yijian in 1050 C.E., as well as Shen Kuo's armillary sphere of the later eleventh century, but after that point they were no longer employed on Chinese armillary instruments until the arrival of the European Jesuits.

Mathematics

Li added corrections to certain mathematical works. Examples of this are in Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art by Liu Hui. In it, he demonstrated that the least common multiple of the numbers two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, and twelve was 27,720. Yet another instance of this was in Zu Geng's work on the area of a sphere. Li gave 22/7 (3.1428571428571428571428571428571) instead of three as a better approximation of what we know now as pi. He began each annotation with the words, “Your servant, Chunfeng, and his collaborators comment respectfully on…”

Although Li also wrote some mathematical works of his own, little is know about them. With Liang Shu and Wang Zhenru, he also wrote Shibu Suanjing (十部算经) in 656. These were ten mathematical manuals submitted to the emperor.

Literary works

Li wrote about the discoveries in astrology, metrology, and music to the Book of Sui and Book of Jin. The Book of Sui (Traditional Chinese: 隋書; Simplified Chinese: 隋书; pinyin: Suīshū) was the official history of the Chinese dynasty Sui Dynasty, and it ranks among the official Twenty-Four Histories of imperial China. It was compiled by a team of historians led by the Tang Dynasty official Wei Zheng and was completed in 636. The Book of Jin (Chinese: 晉書) is one of the official Chinese historical works. It covers the history of Jin Dynasty from 265 to 420, which written by a number of officials commissioned by the court of Tang Dynasty, with the lead editor being the Prime Minister Fang Xuanling, drawing mostly from the official documents left from the earlier archives. A few of the essays in the biographical volume 1, 3, 54 and 80th were composed by Emperor Taizong of Tang himself. Its contents, however, included not only the history of the Jin but also the history of the Sixteen Kingdoms which were contemporaneous with the Eastern Jin. The book was compiled in 648.

The book, Massage-Chart Prophecies, is generally credited to Li. The book is a collaboration of attempts to predict the future using numerology. Therefore, Li is often thought of as being a prophet. The book gets it title from a poem near the end, discussing how much time it would take to tell the story of thousands of years and that it would be better to take a break and enjoy a massage. Li wrote a book which discusses the importance of astrology in Chinese culture called Yisizhan in 645.

He also wrote Commentary on and Introduction to the Gold Lock and the Flowing Pearls. In this book, he describes Taoist customs.

Legacy

Li Chunfeng was an astronomer and a major Feng shui theorist of the Tang Dynasty. Feng shui scholars interpreted constellations and provided advice for all kinds of occasions, from small everyday matters to historical decisions. For example, when a ruler goes to war, advisers use such theories to select the best day to embark. In addition, the legitimacy of the Emperor rested on the Mandate of Heaven, for which astronomers and Feng shui scholars played a key role. Li designed the Linde calendar, and wrote extensively about the discoveries in astronomy, astrology, meteorology, mathematics, and music.

During the Tang Dynasty, Feng shui theory reached its maturity. It was applied to almost all facets of life. For example, the shape of a tomb or house could result in good or bad fortune, which would in turn affect one's life. Li Chungeng was one of the most popular Feng shui masters during the Tang Dynasty and his writings are classic textbooks for the study of Feng shui.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 2000yyds, Chinese Feng shui (Japanese). Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 343.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 350.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- 2000yyds. Chinese Feng shui (Japanese). Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- Aylward, Thomas F. The Imperial Guide to Feng-Shui & Chinese Astrology: The Only Authentic Translation from the Original Chinese. London: Watkins, 2007. ISBN 9781842931752.

- Bennell, Terry, Alistair Michie, Mike Shrimpton, Richard Harvey, John Shrapnel, and Steve Baker. The Power to Predict Chinese Astronomy and the Mandate of Heaven. New Jersey: Films for the Humanities & Sciences, 2004.

- Deane, Thatcher Elliot. The Chinese Imperial Astronomical Bureau: Form and Function of the Ming Dynasty Qintianjian from 1365 to 1627. Thesis (Ph. D.)—University of Washington, 1989, 1989.

- Li, Chunfeng, Tian'gang Yuan, and Pʻu-shêng Yen. The Great Prophecies of China. New York: Franklin Co, 1950.

- Needham, Joseph, and Ling Wang. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol.3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986.

- Needham, Joseph. Heavenly Clockwork; The Great Astronomical Clocks of Medieval China. Cambridge: Published in association with the Antiquarian Horological Society at the University Press, 1960.

- Pankenier, David W. Early Chinese Astronomy and Cosmology: The "Mandate of Heaven" As Epiphany. Thesis (Ph. D.)—Stanford University, 1983, 1987.

- Stephenson, F. Richard, Zhentao Xu, and Yaotiao Jiang. Astronomical Observations of Ancient East Asia. Wiley-Praxis series in astronomy and astrophysics. New York: J. Wiley, 1996. ISBN 9780471960171.

- Xu, Zhentao, David W. Pankenier, and Yaotiao Jiang. East Asian Archaeoastronomy: Historical Records of Astronomical Observations of China, Japan and Korea. Amsterdam: Published on behalf of the Earth Space Institute by Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, 2000. ISBN 9789056993023.

- Zhuang, Tianshan. "Li Chunfeng." Retrieved January 19, 2009.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.