Difference between revisions of "Kalahari Desert" - New World Encyclopedia

Vicki Phelps (talk | contribs) (→Plants) |

Vicki Phelps (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | The Kalahari | + | The Kalahari has existed as an inland desert since the [[Cretaceous]] (65-135 million years ago). It has experienced both periods of greater [[humidity]] and more [[aridity]], documented in fossil dune fields. It was during a period of greater rainfall that the Makgadikgadi Depression in northern [[Botswana]] was formed. The former lake at one point covered 23,000 sq mi (60,000 sq. km), about the same size as Lake Victoria today. The dry riverbeds that now only hold water when it rains are also from such periods. |

| + | The first European to cross the Kalahari was [[David Livingstone]], accompanied by William C. Oswell, in 1849. In 1878-1879 a party of [[Boer]]s, with about three hundred wagons, trekked from the Transvaal across the Kalahari to Ngami and thence to the hinterland of Angola. Survivors stated that some 250 people and 9,000 cattle died on the journey. | ||

==Climate== | ==Climate== | ||

| − | Derived from the Tswana word ''Keir'', meaning the ''great thirst'', or the tribal word ''Khalagari'' or ''Kalagare'' (meaning "a waterless place"<ref name=SAltena>Mary Sadler-Altena, "Kalahari: Introduction" webpage: {{dlw|http://www.southerncape.co.za/geography/regions/kalahari/welcome.html|SouthernCape-Kalahari}}: Kalahari name/climate/reserves and history.</ref>), the Kalahari has vast areas covered by red-brown sands without any permanent surface water. Drainage is by dry valleys, seasonally inundated pans, and the large [[salt pan (geology)|salt pan]]s of the Makgadikgadi Pan in Botswana and Etosha Pan in Namibia. However, the Kalahari is not a true desert. Parts of the Kalahari receive over 250 mm of erratic rainfall annually and are quite well vegetated; it is only truly arid in the | + | Derived from the Tswana word ''Keir'', meaning the ''great thirst'', or the tribal word ''Khalagari'' or ''Kalagare'' (meaning "a waterless place"<ref name=SAltena>Mary Sadler-Altena, "Kalahari: Introduction" webpage: {{dlw|http://www.southerncape.co.za/geography/regions/kalahari/welcome.html|SouthernCape-Kalahari}}: Kalahari name/climate/reserves and history.</ref>), the Kalahari has vast areas covered by red-brown sands without any permanent surface water. Drainage is by dry valleys, seasonally inundated pans, and the large [[salt pan (geology)|salt pan]]s of the Makgadikgadi Pan in Botswana and Etosha Pan in Namibia. |

| + | |||

| + | However, the Kalahari is not a true desert. Parts of the Kalahari receive over 250 mm of erratic rainfall annually and are quite well vegetated; it is only truly arid in the southwest (under 175 mm of rain annually), making the Kalahari a fossil desert. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Summer temperatures in the Kalahari range from 20 to 40°C. In winter, the Kalahari has a dry, cold climate with frosts at night. The low winter temperature can average below 0°C. | ||

==Game reserves== | ==Game reserves== | ||

| Line 47: | Line 52: | ||

==Natural resources== | ==Natural resources== | ||

===Minerals=== | ===Minerals=== | ||

| − | There are large [[coal]], [[copper]], [[nickel]], and [[uranium]] deposits in the region. One of the largest [[diamond]] mines in the world is located at Orapa in the Makgadikgadi, | + | There are large [[coal]], [[copper]], [[nickel]], and [[uranium]] deposits in the region. One of the largest [[diamond]] mines in the world is located at Orapa in the Makgadikgadi, in the northeastern Kalahari. Pomfret, on the edge of the desert, has [[asbestos]] in the subsoil and a shuttered asbestos mine.<ref>{{cite web |

|url=http://www.abc.net.au/foreign/content/2005/s1496370.htm | |url=http://www.abc.net.au/foreign/content/2005/s1496370.htm | ||

|title=South Africa - Pomfret | |title=South Africa - Pomfret | ||

| Line 53: | Line 58: | ||

|accessdate=2007-01-03 | |accessdate=2007-01-03 | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Plants=== | ===Plants=== | ||

| Line 63: | Line 66: | ||

Despite media attention and and heavy marketing by nutritional supplement companies, researchers say Hoodia has not been conclusively demonstrated to work as an appetite suppressant. No published peer-reviewed double-blind clinical trials have been performed on humans to investigate the safety or effectiveness of ''Hoodia gordonii'' in pill form as a nutritional supplement. | Despite media attention and and heavy marketing by nutritional supplement companies, researchers say Hoodia has not been conclusively demonstrated to work as an appetite suppressant. No published peer-reviewed double-blind clinical trials have been performed on humans to investigate the safety or effectiveness of ''Hoodia gordonii'' in pill form as a nutritional supplement. | ||

| − | Plants in the Kalahari follows a number of strategies to deal with | + | Plants in the Kalahari follows a number of strategies to deal with the extreme conditions found there: |

| − | Extremely deep root system | + | * Extremely deep root system: for example, the Camel Thorn Tree, ''Acacia erioloba'', has roots up to 40 meters long. |

| + | * Large underground tubers, with a small exposed part: Many little-known Kalahri plants follow this route. | ||

| + | * Extremely rapid growth cycle: the Devils thorn, ''Tribulus terestris'', that completes its complete life cycle from germination to flowering and seed-forming within as little as two weeks, is a typical example. | ||

| + | * By forming large and treelike to shrublike forms of the same plant, depending on local conditions: The Grey Camel thorn, ''Acacia haematoxylon'', is a prime example of this. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 77: | ||

* Marq de Villiers and Sheila Hirtle, ''Into Africa: A Journey through the Ancient Empires'', 1997. Key Porter Books, Toronto, Canada. ISBN 1550138847 | * Marq de Villiers and Sheila Hirtle, ''Into Africa: A Journey through the Ancient Empires'', 1997. Key Porter Books, Toronto, Canada. ISBN 1550138847 | ||

*''Go2Africa'' [[http://www.go2africa.com/botswana/central-kalahari/central-kalahari-area/]], retrieved April 2, 2007. | *''Go2Africa'' [[http://www.go2africa.com/botswana/central-kalahari/central-kalahari-area/]], retrieved April 2, 2007. | ||

| + | * Marco C. Stoppato and Alfredo Bini, ''Deserts'', 2003. Firefly Books, Buffalo, NY. ISBN 1552976696 | ||

| + | * Sara Oldfield, ''Deserts: The Living Drylands'', 2004. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. ISBN 026215112X | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 17:51, 8 April 2007

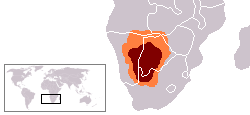

The Kalahari Desert is a large arid to semi-arid sandy area in southern Africa, covering much of Botswana and parts of Namibia and South Africa. Though it is semi-desert, it has huge tracts of excellent grazing after good rains[1] and, in fact, is rich in wildlife.

The distinctive Kalahari Desert is something of a misnomer as it is not really a desert, but a semi-arid zone with a unique atmosphere all its own.

Distinctly different from a true desert region, a strange, yet essential feature of this region is the pans. They are neither round nor circular and consist of hard, gray clay. They are shallow hollows, which gleam in the harsh sun of the Kalahari Desert. Yet these pans provide the essential salt for the animals of the Kalahari. The view created by these pans is drab and flat. They vary in size from a few hundred metres to a few square kilometres. There are two other distinct ecosystems found in the central Kalahari region; rich savannah and flowing golden grasslands.

extending 540,000 square miles (900,000 km²)The surrounding Kalahari Basin covers over 2.5 million km² extending farther into Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, and encroaching into parts of Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The only permanent river, the Okavango, flows into a delta in the northwest, forming marshes that are rich in wildlife. Ancient dry riverbeds—called omuramba—traverse the central northern reaches of the Kalahari and provide standing pools of water during the rainy season. Previously havens for wild animals from elephant to giraffe, and for predators such as lion and cheetah, the riverbeds are now mostly grazing spots, though leopard or cheetah can still be found.

History

The Kalahari has existed as an inland desert since the Cretaceous (65-135 million years ago). It has experienced both periods of greater humidity and more aridity, documented in fossil dune fields. It was during a period of greater rainfall that the Makgadikgadi Depression in northern Botswana was formed. The former lake at one point covered 23,000 sq mi (60,000 sq. km), about the same size as Lake Victoria today. The dry riverbeds that now only hold water when it rains are also from such periods.

The first European to cross the Kalahari was David Livingstone, accompanied by William C. Oswell, in 1849. In 1878-1879 a party of Boers, with about three hundred wagons, trekked from the Transvaal across the Kalahari to Ngami and thence to the hinterland of Angola. Survivors stated that some 250 people and 9,000 cattle died on the journey.

Climate

Derived from the Tswana word Keir, meaning the great thirst, or the tribal word Khalagari or Kalagare (meaning "a waterless place"[1]), the Kalahari has vast areas covered by red-brown sands without any permanent surface water. Drainage is by dry valleys, seasonally inundated pans, and the large salt pans of the Makgadikgadi Pan in Botswana and Etosha Pan in Namibia.

However, the Kalahari is not a true desert. Parts of the Kalahari receive over 250 mm of erratic rainfall annually and are quite well vegetated; it is only truly arid in the southwest (under 175 mm of rain annually), making the Kalahari a fossil desert.

Summer temperatures in the Kalahari range from 20 to 40°C. In winter, the Kalahari has a dry, cold climate with frosts at night. The low winter temperature can average below 0°C.

Game reserves

The Kalahari has a number of game reserves, includng the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), the world's second largest protected area); Khutse Game Reserve; and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. The area's remoteness, unforgiving climate, and harsh terrain have kept it pristine. Animals that live in the region include brown hyenas, lions, meerkats, several species of antelope (including the oryx or gemsbok), warthogs, cheetahs, wild dogs, leopards, and many species of birds and reptiles. Vegetation in the Kalahari consists mainly of grasses and acacias but there are over four hunded identified plant species present (including the wild watermelon or tsamma melon).

A few solitary mopane, camel thorn, Kalahari apple and silver custer-leaf trees stand in isolation in this amazing sea of shimmering grass. Four fossil rivers twist and turn through the arid reserve. Among them is Deception Valley, a dusty old watercourse that wound its way through the Northern Kalahari 16,000 years ago and is today a brilliant game watching area.

A variety of grasses, acacia, thorn trees and other tough, drought-resistant plants cover most of Central Kalahari Game Reserve. Among the shallow valleys, tsamma melons and gemsbok cucumbers are found, which provide the main source of water for the animals and Bushmen during the dry season.

Khutse game reserve

This reserve, the southern extension of the Kalahari Game Reserve, was established to conserve the pans of the Central Kalahari. The reserve’s grass and shrub lands attract the herds of antelope, and these in turn attract the attention of the endangered predators, such as cheetah and wild dog. After a good rainfall you may spot as many as 150 species of birds around the pans

For seven years, Mark and Delia Owens lived in tents, doing landmark research on black-maned Kalahari lions and the elusive brown hyena. After surviving violent storms, wildfires, and 120-degree heat during their research, they chronicled their findings in their book Cry of the Kalahari.

Ancestral land

The area is the ancestral land of the Bushmen (San) peoples. There are many distinct tribes, and they have no collective name for themselves. The names San and Basarwa are sometimes used, but the people themselves dislike these names (San is a Khoikhoi word meaning outsider, and Basarwa a Herero word meaning person who has nothing) and prefer the name "Bushman". Their language, Khoisan, is a language of clicks. The name Bushmen was given to them by early settlers who may have named them for the fact they live in the bush or it might have been given because of their use of aromatic spices collected from various bushes. They are thought to have been the first human inhabitants of Southern Africa; there is evidence that they have been living there continuously as nomadic hunter-gatherers for over twenty thousand years.

The Bushmen were first brought to the Western world's attention in the 1950s when South African author Laurens van der Post published his famous book The Lost World of the Kalahari, which was also turned into a BBC TV series. This and other later works about the Kalahari prompted the British colonial authorities to create the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in 1961 to preserve the Bushmen and the wildlife. After independence, Botswana provided food, water, and medical care to them, but eventually they began raising goats and planting crops. Wildlife officials were concerned about the impact on the environment and the government balked at providing services to remote villages. About three thousand of the estimated hundred thousand remaining Bushmen moved into settlements.

Some two hundred, however, sued the government of Botswana for the right to return to their homeland, and the High Court ruled in December 2006 that the Bushmen are entitled to live and hunt on their ancestral lands. However, the government placed limits on what they could take with them. They cannot bring domesticated animals with them or build permanent structures. Hunters will have to apply for permits. And only those named in the original lawsuit may return.

Today the Bushmen are offering a taste of their life to tourists to bring in money. Bushman activities that can be experienced by visitors include identifying natural salt/mineral licks, medicinal plants, trees, bushes, spoor, birds, and other animals; gathering and preparing foods; learning their dances and playing the foot bow. They can go on a guided simulation hunt and watch demonstrations of traditional skills, such as making "jewelry" from ostrich eggshells, glass beads and seeds; tanning skins and curing hides; and making rope and glue.

Natural resources

Minerals

There are large coal, copper, nickel, and uranium deposits in the region. One of the largest diamond mines in the world is located at Orapa in the Makgadikgadi, in the northeastern Kalahari. Pomfret, on the edge of the desert, has asbestos in the subsoil and a shuttered asbestos mine.[2]

Plants

The Kalahari Desert contains many unique plants, including medicinal plants whose uses have been learned from the Bushmen. The great value of Devil’s claw or Harpagophytum, as a natural medicine was learned by the Germans (from the Bushmen). This resulted in a multimillion-dollar international industry, which incidentally led to the local extinction of the plant in many areas.

The latest wonder medicine to come from the Kalhari is "Hoodia," touted as an appetite suppressant. The South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) discovered the valuable properties of one species of this plant in the 1970s and extracted and tested the ingredient responsible for its appetite-suppressant effect; it was patented in 1996. The CSIR then granted United Kingdom-based Phytopharm a license, and they collaborated with the pharmaceutical company Pfizer to isolate active ingredients from the extracts and look into synthesizing them for use as an appetite suppressant. Pfizer released the rights to the primary ingredient in 2002. In the same year, CSIR officially recognized the Bushmen's rights over Hoodia, allowing them to take a percentage of the profits and any spin-offs resulting from marketing it.

Despite media attention and and heavy marketing by nutritional supplement companies, researchers say Hoodia has not been conclusively demonstrated to work as an appetite suppressant. No published peer-reviewed double-blind clinical trials have been performed on humans to investigate the safety or effectiveness of Hoodia gordonii in pill form as a nutritional supplement.

Plants in the Kalahari follows a number of strategies to deal with the extreme conditions found there:

- Extremely deep root system: for example, the Camel Thorn Tree, Acacia erioloba, has roots up to 40 meters long.

- Large underground tubers, with a small exposed part: Many little-known Kalahri plants follow this route.

- Extremely rapid growth cycle: the Devils thorn, Tribulus terestris, that completes its complete life cycle from germination to flowering and seed-forming within as little as two weeks, is a typical example.

- By forming large and treelike to shrublike forms of the same plant, depending on local conditions: The Grey Camel thorn, Acacia haematoxylon, is a prime example of this.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- "Court victory proves hollow for Bushmen," Washington Times, January 18, 2007.

- Marq de Villiers and Sheila Hirtle, Into Africa: A Journey through the Ancient Empires, 1997. Key Porter Books, Toronto, Canada. ISBN 1550138847

- Go2Africa [[1]], retrieved April 2, 2007.

- Marco C. Stoppato and Alfredo Bini, Deserts, 2003. Firefly Books, Buffalo, NY. ISBN 1552976696

- Sara Oldfield, Deserts: The Living Drylands, 2004. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. ISBN 026215112X

External links

- Flying to the Kalahari

- "Cry of the Kalahari"

- Central Kalahari Game Reserve Pictures, Botswana

- Dream an electronic dream of the Kalahari

- Tourism and Produce of the Kalahari Region

- Destination information about the Kalahari Desert.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mary Sadler-Altena, "Kalahari: Introduction" webpage: Template:Dlw: Kalahari name/climate/reserves and history.

- ↑ South Africa - Pomfret. abc.net. Retrieved 2007-01-03.