Difference between revisions of "Judah haNasi" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Biography) |

|||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

===Family and education=== | ===Family and education=== | ||

[[Image:Akiba ben joseph.jpg|thumb|150px|left|Rabbi Akiva]] | [[Image:Akiba ben joseph.jpg|thumb|150px|left|Rabbi Akiva]] | ||

| + | Judah haNasi was born in 135. According to the [[midrash]], he came into the world on the same day that Rabbi [[Akiva]] died a martyr's death (Midrash [[Genesis Rabbah]] lviii.; Midrash [[Eccl. Rabbah]] i. 10) The Talmud suggests that this was a result of Divine [[Providence]]: [[God]] had granted the Jewish people another leader of great stature to succeed Akiva. Although the two leaders shared many opinions in common regarding Jewish law, they were polar opposites in terms of their attitude toward Rome. Whereas, Akiva had supported Simon [[Bar Kochba]]'s violent revolt against Rome, even declaring him to be the promised [[Messiah]], Judah HaNasi as a trust friend Roman emperors, whose influence helped the Jews, for the most part, improve their lot after decades of suffering from Roman repression. | ||

| + | |||

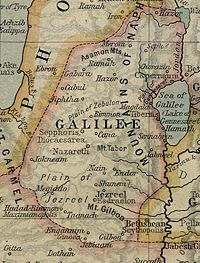

[[Image:Ancient Galilee.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The [[Galilee]] in [[late antiquity]]]] | [[Image:Ancient Galilee.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The [[Galilee]] in [[late antiquity]]]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | On the restoration of order in Palestine, the western Galilean town of Usha became the seat of the [[Sanhedrin]], the Jewish rabbinical court. | + | Judah's place of birth is unknown. His father, [[Shimon ben Gamliel II]], had probably been at the fortress of Betar with Bar Kochba when that fortress was taken by the Romans, but he managed to escape the massacre (Gittin 58a; Sotah 49b; Bava Kamma 83a; Jer. Ta'anit 24b). On the restoration of order in Palestine, the western Galilean town of Usha became the seat of the [[Sanhedrin]], the Jewish rabbinical court. Shimon was elected as its president, this dignity reportedly being bestowed upon him both because of his personal qualities and because of his connections with the house of [[Hillel]], whose attitude toward Gentiles (especially the Romans) had been not been overtly hostile. Shimon was recognized by the Romans as the Jewish [[patriarch]], and his attitude toward Rome must have been basically cooperative. |

| − | Judah | + | Judah thus spent his youth youth at Usha in probably the most wealthy and prestigious Jewish home in the [[Roman Empire]]. In addition to the classic Jewish texts, his studies certainly included [[Greek]]. He is reported to have held that the Jews of [[Palestine]] who did not speak [[Hebrew]] should consider Greek as the language of their country, while Syriac ([[Aramaic]]) had no claim to that distinction. In Judah's own house, pure Hebrew seems to have been spoken. |

| − | Judah also speaks of studying with of Simeon bar Yochai and | + | However, Judah devoted himself chiefly to the study of the [[halakha|Jewish law]]. In his youth he had close relations with most of the great pupils of [[Akiva]], and a number of anecdotes are preserved by in the [[Talmud]] concerning their discussions. He thus laid the foundations which enabled him to undertake his life's work, the redaction of the [[Mishnah]]. His teacher at Usha was [[Judah ben Ilai]], who was officially employed in the house Judah's father as a judge in religious and legal questions (Men. 104a; Sheb. 13a). |

| + | |||

| + | Judah also speaks of studying with of Akiva's pupils [[Simeon bar Yochai]] and [[Eleazer ben Shammua]] but not with the famous [[Rabbi Meir]], evidently because of conflicts which made this famous pupil of Akiva unwelcome in the house of the patriarch in his old age. However, [[Rabbi Nathan]] the Babylonian, who also took a part in the conflict between Meir and the patriarch, was another of Judah's teachers. In [[halakha|halakhic]] as well as in [[Aggadah|aggadic]] tradition, Judah's opinion is often opposed to Nathan's. Finally, in the list of Judah's teachers, his own father must not be omitted. As with Rabbi Nathan, the view of Judah son is often opposed to that of his father in halakhic tradition, the latter generally advocating the less rigorous position. Judah himself says: "My opinion seems to me more correct than that of my father." ('Er. 32a) Despite his willingness to disagree with his father, humility was a virtue ascribed to Judah, and he admired it greatly in his father. | ||

===Judah's academy and patriarchate=== | ===Judah's academy and patriarchate=== | ||

| − | Eventually, Judah came to succeeded his father as leader of the Palestinian Jews. According to a tradition (Mishnah Soṭah, end), the country at the time of Simon ben Gamaliel's death was devastated by a plague of locusts and many other hardships. This may be the reason why Judah transferred the seat of the patriarchate and of the academy to another place in Galilee, namely, Beit She'arim. Here he officiated for a long time. However, during the last 17 years of his life he lived at [[Sepphoris]], where he settled on account of its high altitude and pure air (Yer. Kil. 32b; Gen. R. xcvi.; Ket. 103b). However, it is at Beit She'arim that his activity as director of the academy and chief judge is principally associated | + | Eventually, Judah came to succeeded his father as leader of the Palestinian Jews. According to a tradition (Mishnah Soṭah, end), the country at the time of [[Simon ben Gamaliel]]'s death was devastated by a plague of locusts and many other hardships. This may be the reason why Judah transferred the seat of the patriarchate and of the academy to another place in [[Galilee]], namely, Beit She'arim. Here he officiated for a long time. However, during the last 17 years of his life he lived at [[Sepphoris]], where he settled on account of its high altitude and pure air (Yer. Kil. 32b; Gen. R. xcvi.; Ket. 103b). However, it is at Beit She'arim that his activity as director of the academy and chief judge of the rabbinical court is principally associated. "To Beit She'arim must one go in order to obtain Rabbi's decision in legal matters," says one tradition (Sanh. 32b). The chronology of Judah's activity at Beit She'arim, however, remains speculative. |

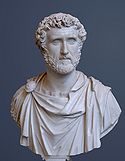

[[Image:Antoninus Pius Glyptothek Munich 337 cropped.jpg|thumb|125px|Antoninus Pius]] | [[Image:Antoninus Pius Glyptothek Munich 337 cropped.jpg|thumb|125px|Antoninus Pius]] | ||

| − | Numerous anecdotes have been preserved in the Talmudic and midrashic literature, relating to Judah's relations with the emperor [[Antoninus Pius]] (d. 161 C.E.), many of which are clearly legendary or spurious. However, | + | Numerous anecdotes have been preserved in the Talmudic and midrashic literature, relating to Judah's relations with the emperor Antoninus, possibly [[Antoninus Pius]] (d. 161 C.E.), many of which are clearly legendary or spurious, since Antoninus was not in office during most of Judah's reign as patriarch. However, [[Marcus Aurelius]] is known to have visited Palestine in 175, as did [[Septimius Severus]] in 200. Thus, Judah probably did have personal relations with one or more Roman emperors. However, many commentators believe that most of the references to the "emperor" actually describe a relationship with various imperial representatives in Palestine. A great deal of splendor surrounds Judah's position in these stories, to a degree that no other occupant of his same office enjoyed. This is likely due the the fact that Judah, more than any previous patriarch, indeed enjoyed particularly amicable relations with the Roman rulers. |

| − | |||

| − | A great deal of splendor surrounds Judah's position in these stories, to a degree that no other occupant of his same office enjoyed. This is likely due the the fact that Judah indeed enjoyed particularly amicable relations with the Roman rulers | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Judah | + | Nevertheless there were also periods during Judah's long patriarchate (some 50 years) when the Jews suffered persecution and other hardships. During a famine, Judah supposedly opened his granaries and distributed grain among the needy (B. B. 8a). However, he denied himself the pleasures which could be obtained by wealth, saying: "Whoever chooses the delights of this world will be deprived of the delights of the next world; whoever renounces the former will receive the latter" (Ab. R. N. xxviii.). |

| − | + | Many religious and legal decisions are recorded as having been rendered by Judah together with his court (Giṭ. v. 6; Oh. xviii. 9; Tosef., Shab. iv. 16; see also Yeb. 79b, above; Ḳid. 71a). Judah was, without doubt, the chief Jewish personage of this period, which marks the close of the epoch of the [[Tannaim]] (early rabbinical sages) in Jewish history, and inaugurates the era of the [[Amoraim]]. | |

| − | + | A early saying of the Talmud demonstrates Judah's importance—that since the time of Moses the Torah no one greater in knowledge and rank, had arisen than Judah ha-Nasi (Giṭ. 59a; Sanh. 36a). | |

==Compiler of the Mishna== | ==Compiler of the Mishna== | ||

Revision as of 00:04, 6 August 2008

Rabbi Judah haNasi, (Hebrew: יהודה הנשיא—"Judah the Prince"), was a key leader of the Jewish community of Judea toward the end of the second during the occupation of the Roman Empire. He is best known as the chief redactor of the Mishnah, the core collection of rabbinical opinions which form the core of the Talmud.

The title nasi refers to his role as president of the Sanhedrin (Jewish legal council), but may also be related to the fact that Judah was supposedly of the royal line of King David, hence the title "Prince."

Unlike his great predecessor Rabbi Akiva, who supported the temporarily successful revolt of the messianic leader Simon Bar Kochba against the Romans, Judah haNasi maintained cordial relations with Rome and was said to enjoyed a personal friendship with at least one Roman emperor. His most important contribution to Judaism, however, was his redaction of the Mishnah, which forms the foundation for all later Talmudic tradition.

Judah thus marks this transition from the era of the ancient sages known as the Tannaim to the era of the great early commentators known as the Amoraim. His contribution to the literary tradition of Judaism can hardly be overstated.

Biography

Family and education

Judah haNasi was born in 135. According to the midrash, he came into the world on the same day that Rabbi Akiva died a martyr's death (Midrash Genesis Rabbah lviii.; Midrash Eccl. Rabbah i. 10) The Talmud suggests that this was a result of Divine Providence: God had granted the Jewish people another leader of great stature to succeed Akiva. Although the two leaders shared many opinions in common regarding Jewish law, they were polar opposites in terms of their attitude toward Rome. Whereas, Akiva had supported Simon Bar Kochba's violent revolt against Rome, even declaring him to be the promised Messiah, Judah HaNasi as a trust friend Roman emperors, whose influence helped the Jews, for the most part, improve their lot after decades of suffering from Roman repression.

Judah's place of birth is unknown. His father, Shimon ben Gamliel II, had probably been at the fortress of Betar with Bar Kochba when that fortress was taken by the Romans, but he managed to escape the massacre (Gittin 58a; Sotah 49b; Bava Kamma 83a; Jer. Ta'anit 24b). On the restoration of order in Palestine, the western Galilean town of Usha became the seat of the Sanhedrin, the Jewish rabbinical court. Shimon was elected as its president, this dignity reportedly being bestowed upon him both because of his personal qualities and because of his connections with the house of Hillel, whose attitude toward Gentiles (especially the Romans) had been not been overtly hostile. Shimon was recognized by the Romans as the Jewish patriarch, and his attitude toward Rome must have been basically cooperative.

Judah thus spent his youth youth at Usha in probably the most wealthy and prestigious Jewish home in the Roman Empire. In addition to the classic Jewish texts, his studies certainly included Greek. He is reported to have held that the Jews of Palestine who did not speak Hebrew should consider Greek as the language of their country, while Syriac (Aramaic) had no claim to that distinction. In Judah's own house, pure Hebrew seems to have been spoken.

However, Judah devoted himself chiefly to the study of the Jewish law. In his youth he had close relations with most of the great pupils of Akiva, and a number of anecdotes are preserved by in the Talmud concerning their discussions. He thus laid the foundations which enabled him to undertake his life's work, the redaction of the Mishnah. His teacher at Usha was Judah ben Ilai, who was officially employed in the house Judah's father as a judge in religious and legal questions (Men. 104a; Sheb. 13a).

Judah also speaks of studying with of Akiva's pupils Simeon bar Yochai and Eleazer ben Shammua but not with the famous Rabbi Meir, evidently because of conflicts which made this famous pupil of Akiva unwelcome in the house of the patriarch in his old age. However, Rabbi Nathan the Babylonian, who also took a part in the conflict between Meir and the patriarch, was another of Judah's teachers. In halakhic as well as in aggadic tradition, Judah's opinion is often opposed to Nathan's. Finally, in the list of Judah's teachers, his own father must not be omitted. As with Rabbi Nathan, the view of Judah son is often opposed to that of his father in halakhic tradition, the latter generally advocating the less rigorous position. Judah himself says: "My opinion seems to me more correct than that of my father." ('Er. 32a) Despite his willingness to disagree with his father, humility was a virtue ascribed to Judah, and he admired it greatly in his father.

Judah's academy and patriarchate

Eventually, Judah came to succeeded his father as leader of the Palestinian Jews. According to a tradition (Mishnah Soṭah, end), the country at the time of Simon ben Gamaliel's death was devastated by a plague of locusts and many other hardships. This may be the reason why Judah transferred the seat of the patriarchate and of the academy to another place in Galilee, namely, Beit She'arim. Here he officiated for a long time. However, during the last 17 years of his life he lived at Sepphoris, where he settled on account of its high altitude and pure air (Yer. Kil. 32b; Gen. R. xcvi.; Ket. 103b). However, it is at Beit She'arim that his activity as director of the academy and chief judge of the rabbinical court is principally associated. "To Beit She'arim must one go in order to obtain Rabbi's decision in legal matters," says one tradition (Sanh. 32b). The chronology of Judah's activity at Beit She'arim, however, remains speculative.

Numerous anecdotes have been preserved in the Talmudic and midrashic literature, relating to Judah's relations with the emperor Antoninus, possibly Antoninus Pius (d. 161 C.E.), many of which are clearly legendary or spurious, since Antoninus was not in office during most of Judah's reign as patriarch. However, Marcus Aurelius is known to have visited Palestine in 175, as did Septimius Severus in 200. Thus, Judah probably did have personal relations with one or more Roman emperors. However, many commentators believe that most of the references to the "emperor" actually describe a relationship with various imperial representatives in Palestine. A great deal of splendor surrounds Judah's position in these stories, to a degree that no other occupant of his same office enjoyed. This is likely due the the fact that Judah, more than any previous patriarch, indeed enjoyed particularly amicable relations with the Roman rulers.

Nevertheless there were also periods during Judah's long patriarchate (some 50 years) when the Jews suffered persecution and other hardships. During a famine, Judah supposedly opened his granaries and distributed grain among the needy (B. B. 8a). However, he denied himself the pleasures which could be obtained by wealth, saying: "Whoever chooses the delights of this world will be deprived of the delights of the next world; whoever renounces the former will receive the latter" (Ab. R. N. xxviii.).

Many religious and legal decisions are recorded as having been rendered by Judah together with his court (Giṭ. v. 6; Oh. xviii. 9; Tosef., Shab. iv. 16; see also Yeb. 79b, above; Ḳid. 71a). Judah was, without doubt, the chief Jewish personage of this period, which marks the close of the epoch of the Tannaim (early rabbinical sages) in Jewish history, and inaugurates the era of the Amoraim.

A early saying of the Talmud demonstrates Judah's importance—that since the time of Moses the Torah no one greater in knowledge and rank, had arisen than Judah ha-Nasi (Giṭ. 59a; Sanh. 36a).

Compiler of the Mishna

Judah's great fame in Jewish tradition, however, is not due to his political or juridical leadership nearly so much as it is to his great intellectual work of compiling at redacting the Mishnah, which in turn came to serve as the core teaching of the Talmud. According to Jewish tradition, God gave the Jewish nation not only the Written Law but also an Oral Law, both of which were revealed to Moses at Mount Sinai. The Oral Law was passed down over the centuries by the prophets, sages, and rabbis. Fearing that these oral traditions might be forgotten due to the scattering of the Jews after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E. and the later failure of the Bar Kochba revolt, Judah HaNasi undertook the mission of compiling them. His work, which later came to be known as the Mishnah, consists of 63 tractates dealing with rabbinical discussion of Jewish law.

No definite statements have been preserved regarding the exact process of Judah's redaction of the Mishnah. However, the Mishnah contains many of Judah's own sentences. These are introduced by the words, "Rabbi says," leading to the view of many commentators the the mature form of the work is not Judah's product. The work is believed to have been completed after Judah's death, sentences by his son and successor, Gamaliel III.

Both the Babylonian Talmud and its Palestinian counterpart assume as a matter of course that Judah is the originator of the Mishnah. However, the Mishnah, like all the other literary documents of Jewish tradition, is a compilation of many rabbinical opinions and traditions. Hence Judah is correctly called its redactor, and not its author. The Halakhah (Jewish legal tradition) found its authoritative—though by no means final—expression in Judah's Mishnah. It reportedly follows the systematic division of the halakhic material formulated by Akiva, as taught to Judah by Meir, Akiba's foremost pupil (Sanh. 86a).

Judah had no small task in selecting the material that he included in his work. The fact that he did not invariably lay down the rule, but always admitted divergent opinions and traditions of Akiva's eminent pupils, evidences his consciousness of the limits imposed upon his authority by tradition and by conscience.

Judah's character

Judah was reportedly easily moved to tears. He exclaimed, sobbing, in reference to three different stories of the Jewish martyrs: "One man earns his world in an hour, while another requires many years" ('Ab. Zarah 10b, 17a, 18a). He also began to weep when Elisha ben Abuya's daughters, who were soliciting alms, reminded him of their father's learning (Yer. Ḥag. 77c; comp. Ḥag. 15b). And in a legend relating to his meeting with Phinehas ben Jair (Ḥul. 7b) he is represented as tearfully admiring the pious Phinehas' unswerving steadfastness. He was frequently interrupted by tears when speaking of the destruction of Jerusalem and of the Temple (Lam. R. ii. 2; comp Yer. Ta'an. 68d).He was also discovered weeping during his last illness because death was about to deprive him of the opportunity of studying the Torah and of fulfilling the commandments (Ket. 103b).

He recited daily the following supplication on finishing the obligatory prayers (Ber. 6b; comp. Shab. 30b): "May it be Thy will, my God and the God of my fathers, to protect me against the impudent and against impudence, from bad men and bad companions, from severe sentences and severe plaintiffs, whether a son of the covenant or not."

In regard to the inclination to sin ("yetzer hara") he said: "It is like a person facing punishment on account of robbery who accuses his traveling companion as an accomplice, since he himself can no longer escape. This bad inclination reasons in the same way: 'Since I am destined to destruction in the future world, I will cause man to be destroyed also'" (Ab. R. N. xvi.).

Judah's sentence, "Let thy secret be known only to thyself; and do not tell thy neighbor anything which thou perceivest may not fitly be listened to" (Ab. R. N. xxviii.), exhorts to self-knowledge and circumspection. On the other hand, he retained the ancient world's fundamental prejudice against women: "The world needs both the male and the female: but happy he who has male children; and woe to him who has female children." (Pes. 65a; Ḳid. 82b; comp. Gen. R. xxvi.).

Judah praises the value of work by saying that it protects both from gossip and from need (Ab. R. N., Recension B, xxi.). For him, the order of the world depends on justice (A. V. "judgment," Prov. xxix. 4). Zion is delivered by justice (Isa. i. 27); and the pious are praised for their justice (Ps. cvi. 3).

Various stories are told about Judah HaNasi, illustrating different aspects of his character. One of them exemplifies his strictness. It tells of a calf being led to slaughter that broke free and tried to hide under Judah HaNasi's robes, bellowing with terror. Yehuda pushed the animal away, saying: "Go; for this purpose you were created." Judah HaNasi was afflicted with kidney stones, painful flatulence, and other gastric problems. He prayed for relief, but his prayers were ignored, just as he had ignored the pleas of the calf.

Another exemplifies his quality of mercy. One day, Judah HaNasi's maid (or daughter) found some baby weasels in the house and was about to expel them violently with her broom. Judah stopped her, saying, "Leave them alone! It is written: 'His Mercy is upon all his works.'" A this saying a voice from Heaven was heard: "Since he has shown compassion, let us be compassionate with him." The rabbi was then healed of his painful illnesses and could once again go out in public.

Death and legacy

| Rabbinical Eras |

|---|

Judah's death is recorded in a touching account (Yer. Kil. 32b; Ket. 104a; Yer. Ket. 35a; Eccl. R. vii. 11, ix. 10) which relates that no one had the heart to announce his demise to the anxious people of Sepphoris. The clever Bar Ḳappara broke the news to them in a parable in which heaven and earth were engaged in a kind of tug-of-war over the great rabbi: "The heavenly host and earth-born men held the tablets of the covenant; then the heavenly host was victorious and seized the tablets." According to the one Talmudic traditions, Judah was buried at Beit She'arim, where he had long since prepared his tomb (Ket. 103b); but, according to the work "Gelilot Eretz Yisrael," his tomb was at Sepphoris.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Judah Hanasi's legacy for Judaism. Not only did his patriarchate restore amicable relations between the Jews and Romans after the tragic consequence of the Bar Kochba rebellion in which upwards of 100,000 Jewish lives may have been lost and the Jews were expelled from Jerusalem. More importantly, his collection and redaction of the Mishnah created the the halakhic core around which the Talmudic tradition would be built. It was this work which preserved in written the supposed Oral Law which gave later Judaism its basic character.

While some Jews, notably the Karaites and today's Reform Jews, reject the Mishnah and the Talmud as binding, Judah HaNasi stands as one of the greatest figures of rabbinic Judaism.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.