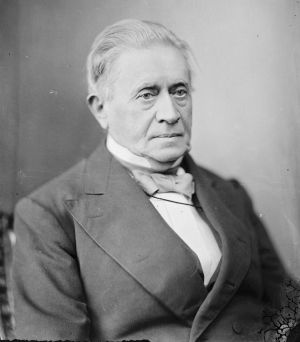

Joseph Henry

|

Joseph Henry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

December 17 1797 |

| Died | May 13 1878 (aged 80) |

Joseph Henry (December 17 1797 – May 13 1878) was a Scottish-American scientist whose inventions and discoveries in the fields of electromagnetism and magnetic induction helped launch the age of electrodynamics. Henry served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, which he shaped into the organization it is today. His contributions led to the successful implementation of the telegraph by Samuel F.B. Morse.

The SI unit of inductance, the henry, is named after Joseph Henry.

Life

Joseph Henry was born on December 17th, 1799 in Albany, New York to two immigrants from Scotland, Ann Alexander Henry and William Henry. His parents were poor, and Joseph’s father died while he was still a young boy. Henry was sent to live with his grandmother in Galway, Saratoga County, New York when he was seven. His father died a few years later. From the age of ten he worked at a general store, and attended school in the afternoons. It was while living in Galway that he accidentally stumbled across the village library while chasing his pet rabbit, and from a perusal of its collection developed a keen interest in literature. When he was 14, he moved to Albany to live with his mother, and worked for a brief time as a silversmith, where he developed practical skills that later proved helpful in designing his experiments.

Formal Education

Joseph’s first love was theater and he came very close to becoming a professional actor. He joined a local theater group called the Rostrum, for which he wrote plays and created set designs. Once, while ill for a few days, he picked up a book left by a boarder in his home, Popular Lectures on Experimental Philosophy, Astronomy and Chemistry, by G. Gregory. This book so inspired him that he soon gave up stage management, and in 1819, entered The Albany Academy, where he was given free tuition, and supported himself with teaching and private tutoring positions. He left the academy to prepare for a career in medicine while studying higher mathematics. But in 1824, he was appointed an assistant engineer for the survey of the State road being constructed between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. From then on, he was inspired to a career in civil or mechanical engineering.

Researches in electricity and magnetism

Henry excelled at his studies (so much so, that he would often be helping his teachers teach science) and, by 1826, he joined the academy staff as an assistant, and was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy by Principal T. Romeyn Beck two years later.

Henry's curiosity about terrestrial magnetism lead him to experiment with magnetism in general. In 1827, he read his first paper, On some modifications of the electro-magnetic apparatus. He was the first to coil insulated wire tightly around an iron core in order to make an extremely powerful electromagnet, improving on William Sturgeon’s electromagnet, which used loosely coiled uninsulated wire. Using this technique, he built the most powerful electromagnet at the time for Yale. He also showed that, when making an electromagnet using just two electrodes attached to a battery, it is best to wind several coils of wire in parallel, but when using a set-up with multiple batteries, there should be only one single long coil. The latter made the telegraph feasible.

In 1829, Henry discovered the property of self inductance in a spool of wire, a phenomenon that was discovered independently by Michael Faraday. Henry did not publish his results, however, until after Faraday had published his in 1834, and thus the discovery is generally credited to Faraday. Once Henry realized that Faraday had already published his results, he always credited the Faraday with the discovery.

Henry married the daughter of one of the professors at the academy in 1830. The couple had a son and three daughters who survived early childhood.

In 1831, Henry created one of the first machines to use electromagnetism for motion. This was the earliest ancestor of modern DC motor. It did not make use of rotating motion, but was merely an electromagnet perched on a pole, rocking back and forth. The rocking motion was caused by one of the two leads on both ends of the magnet rocker touching one of the two battery cells, causing a polarity change, and rocking the opposite direction until the other two leads hit the other battery. Henry also developed a mechanism for sending a signal through a mile of electrical wire that rang a bell.

Professorship at Princeton

Based on his accomplishments in the fields of electricity and magnetism, through which he had obtained widespread notoriety, Henry was invited to join the teaching staff of The College of New Jersey, later named Princeton University, as professor of Natural Philosophy. While at Princeton, he discovered that an electrical current could be induced from one coil to another in a separate circuit, and that this could occur at a distance at least of many feet. He also found that he could alter the current and voltage induced in a secondary coil by changing the number of windings in the coil.

What is perhaps one of Henry's most remarkable discoveries is the oscillatory nature of a current produced by an electric coil in conjunction with a leyden jar. A leyden jar is a simple device, a glass jar, in fact, with a conductor on both the outside and the inside. The inside conductor is merely a chain that hangs from a stopper at the top of the jar. The stopper also insulates the chain from the jar, while the other conductor is merely a coating on the outside of the jar, usually near its base. A charge can be stored in a leyden jar, and discharged at will by connecting the inside and outside conductors.

Henry found that by putting a coil of conducting wire in the circuit, an oscillating current is produced when the leyden jar is discharged. This is precisely the mechanism that was used to discover radio waves by Heinrich Hertz some 50 years later. Around this time, Henry invented the electrical relay switch, which was activated by turning an electromagnet on and off.

In 1837, Henry traveled to Europe, where he met Wheatstone, who was busy developing a telegraph, as well as many noted scientists on the Continent, such as Biot, Arago, Becquerel, Gay-Lussac and De la Rive. He also lectured at the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Edinburgh.

First secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

In 1829, James Smithson, an Englishman of wealth, bequeathed a large sum to the Federal Government of the United States, to establish an institution for "the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men..." <<<Youmans, William Jay. 1896. Pioneers of science in America sketches of their lives and scientific work. New York: D. Appleton. 361.>>>The government was at first at a loss as to how to carry out this bequest, but by 1846, a board of regents had been formed to implement Smithson's wishes. After consulting Henry about how the board might proceed, Henry so impressed the members with his ideas that in December of the same year they elected him secretary of the Smithsonian Institution thus formed. Henry remained at this post for the remainder of his life. In fact, so strongly did he hold to his commitment to the institution that he turned down a professorship at the University of Pennsylvania, and the presidency of Princeton. He organized the Smithsonian as the primary center for the publication of original scientific work and for communication fo the results of research worldwide. It was his goal to ensure that the Smithsonian's efforts did not duplicate what other government agencies were already doing.

The Smithsonian's first publication was issued in 1848 - Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, Edited Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin H. Davis.

In 1852, Henry was appointed a member of the Lighthouse Board, and in 1871, became its president. His research demonstrated that lard would be a more effective fuel for lighting than whale oil, which had been used up to that time and which was becoming prohibitively expensive.

Researches at the Smithsonian

While administrative tasks dominated most of his time after his appointment, he still found time for research. In 1848, he worked in conjunction with Professor Stephen Alexander to determine the relative temperatures for different parts of the solar disk. They determined that sunspots were cooler than the surrounding regions. This work was shown to the astronomer Angelo Secchi who extended it, but with some question as to whether Henry was given proper credit for his own earlier work.

Henry developed a thermal telescope with which he made observations of clouds, and performed experiments on capillary action between molten and solid metals. He also made important contributions to the science of acoustics. [1]

Later years

In 1863 Henry cofounded the National Academy of Sciences. He became the organization's second president in 1868.

As a famous scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institution, he received visits from other scientists and inventors who sought his advice. Henry was patient, kindly, self-controlled, and gently humorous.[2]

Henry was introduced to Prof. Thaddeus Lowe, a balloonist from New Hampshire who had taken interest in the phenomena of lighter-than-air gases, and exploits into meteorology, in particular, the high winds which we call the Jet stream today. It was Lowe's intent to make a transatlantic crossing via an enormous gas-inflated aerostat. Henry took a great interest in Lowe's endeavors so much as to support and promote him among some of the more prominent scientists and institutions of the day.

At the onset of civil war, Lowe, with Henry's endorsement, went to Washington, where he served the union forces as a ballonist.

Another inventor Henry took an interest in was Alexander Graham Bell who on March 1, 1875 carried a letter of introduction to Henry. Henry showed an interest in seeing Bell's experimental apparatus and Bell returned the following day. Henry advised Bell not to publish his ideas until he had perfected the invention.

On June 25 1876, Bell's experimental telephone (using a different design) was demonstrated at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia where Joseph Henry was one of the judges for electrical exhibits. On January 13, 1877 Bell demonstrated his instruments to Henry at the Smithsonian Institution and Henry invited Bell to show them again that night at the Washington Philosophical Society. Henry praised "the value and astonishing character of Mr. Bell's discovery and invention."[3]

In December of 1877, Henry suffered an attack of nephritis, which resulted in partial paralysis. He was able to sustain the effects of the disease until May 13, 1878, the day of his death, until which point he remained coherent and intellectually sound of mind. He was buried a few days later in Oak Hill Cemetery in northwest Washington, D.C.

Legacy

Henry has the unique position of having contributed not only to the progress of science, but also through his administration, to the dissemination of its results. The Smithonsian continues to function as one of America's major research and educational institutions. He came perilously close to inventing both telegraphy and radio. Certainly his discoveries led the way to long-distance transmission of electrical impulses that made the telegraph possible. Although his experiments in sending impulses through the air did not attract major attention at the time, these too could have led to some significant new breakthrough in technology, had not his other work distracted him.

In the case where a scientist is given a task that takes away from research in his major field, one often wonders if more could have been accomplished had he or she been given the freedom to follow their bent of mind. However, it is sometimes these distractions that bring balance to a life, and certainly Henry made a conscious choice to take on the presidency of the Smithsonian rather than devote his life to pure research. His work lives on in his scientific discoveries and in the institutions he helped establish.

See also

Notes

- ↑ An auralization of Henry's experiment

- ↑ Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude, Robert V. Bruce, pages 139-140

- ↑ Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude, Robert V. Bruce, page 214

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ames, Joseph Sweetman, ed. The discovery of induced electric currents, Vol. 1. Memoirs, by Joseph Henry. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company [c1900] LCCN 00005889

- Coulson, Thomas, Joseph Henry: His Life and Work, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1950.

- Henry, Joseph, Scientific Writings of Joseph Henry. Volumes 1 and 2, Smithsoninan Institution, 1886.

- Moyer, Albert E., Joseph Henry: The Rise of an American Scientist, Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997. ISBN 1-56098-776-6

External links

- Published physics papers - On the Production of Currents and Sparks of Electricity from Magnetism and On Electro-Dynamic Induction (extract)

- The Joseph Henry Papers Project

- Biographical details] - Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (1967), 58(1), pages 1 - 10.

- Dedication ceremony for the Henry statue (1883)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.