Riis, Jacob

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

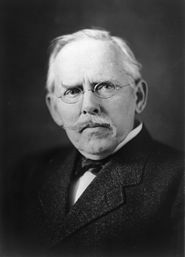

[[Image:Jacob Riis 2.jpg|right|thumb|185px|Jacob Riis in 1906]] | [[Image:Jacob Riis 2.jpg|right|thumb|185px|Jacob Riis in 1906]] | ||

| − | '''Jacob August Riis''' (May 3, 1849 - May 26, 1914), a [[Denmark|Danish]]-[[United States|American]] [[muckraker]] [[journalist]], [[photographer]], and social reformer | + | '''Jacob August Riis''' (May 3, 1849 - May 26, 1914), was a [[Denmark|Danish]]-born [[United States|American]] [[muckraker]] [[journalism|journalist]], [[photography|photographer]], and social reformer. He is known for his dedication to using his photographic and journalistic talents to help the less fortunate in [[New York City]], which was the subject of most of his prolific writings and photographic essays. As one of the first photographers to use [[Flash (photography)|flash]], he is considered a pioneer in [[photography]]. |

| − | ==Early life== | + | ==Biography== |

| − | Jacob Riis was the third of fifteen children | + | |

| + | ===Early life=== | ||

| + | '''Jacob Riis''' was born in Ribe, [[Denmark]], the third of fifteen children of Niels Riis, schoolteacher and editor of the local [[newspaper]], and Carolina Riis, a homemaker. Riis was influenced both by his stern father and by the authors he read, among whom [[Charles Dickens]] and [[James Fenimore Cooper]] were his favorites. At age eleven, Riis's younger brother drowned. Riis would be haunted for the rest of his life by the images of his drowning brother and of his mother staring at his brother's empty chair at the dinner table. At twelve, Riis amazed all who knew him when he donated all the money he received for [[Christmas]] to a poor Ribe family, at a time when money was scarce for anyone. When Riis was sixteen, he fell in love with Elisabeth Gortz, but was rejected. He moved to [[Copenhagen]] in dismay, seeking work as a [[carpentry|carpenter]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Immigration to the United States=== | ||

| + | Riis came to the [[United States]] in 1870, when he was 21, seeking employment as a carpenter. He arrived during an era of social turmoil. Large groups of migrants and immigrants flooded urban areas in the years following the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] seeking prosperity in a more industrialized environment. Twenty-four million people moved to [[urban]] centers, causing a population increase of over 700%. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:Bohemian Cigarmakers.jpg|thumb|left|200 px|Bohemian cigarmakers at work in their tenement]] | [[Image:Bohemian Cigarmakers.jpg|thumb|left|200 px|Bohemian cigarmakers at work in their tenement]] | ||

| − | The demographics of American urban centers grew significantly more heterogeneous as immigrant groups arrived in waves, creating ethnic enclaves often more populous than even the largest cities in the homelands. | + | The demographics of American urban centers grew significantly more heterogeneous as immigrant groups arrived in waves, creating [[ethnicity|ethnic]] enclaves often more populous than even the largest cities in the homelands. Riis found himself just another poor immigrant in [[New York City]]. His only companion was a stray dog he met shortly after his arrival. The dog brought him inspiration and when a police officer mercilessly beat it to death, Riis was devastated. One of his personal victories, he later confessed, was not using his eventual fame to ruin the career of the offending officer. Riis spent most of his nights in police-run poor houses, whose conditions were so ghastly that Riis dedicated himself to having them shut down. |

| + | |||

| + | At the age of 25, Riis wrote to Elisabeth Gortz to propose a second time. This time Gortz accepted, and joined Riis in [[New York City]]. She was a great support in his work. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Journalist career=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Bandit's Roost by Jacob Riis.jpeg|thumb|right|''Bandit's Roost'' by Jacob Riis, 1888, from ''How the Other Half Lives''. The image is taken at 59½ Mulberry Street, considered the most crime-ridden, dangerous part of New York City.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Riis held various jobs before he accepted a position as a police reporter in 1873 with the ''New York Evening Sun'' newspaper. In 1874, he joined the news bureau of the ''Brooklyn News,'' working there for 3 years. In 1877, he became a police reporter, this time for the ''[[New York Tribune]].'' During these stints as a police reporter, Riis worked the most crime-ridden and impoverished slums of the city. Through his own experience in the poor houses, and witnessing the conditions of the poor in the city slums, he decided to make a difference for those who had no voice. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Riis was one of the first [[photography|photographers]] in [[United States]] to use [[flash powder]], allowing his documentation of [[New York City]] slums to penetrate the dark of night, and helping him capture the hardships faced by the poor, especially on the notorious [[Mulberry Street (Manhattan)|Mulberry Street]]. In 1889, ''Scribner's Magazine'' published Riis's photographic essay on city life, which Riis later expanded to create his magnum opus ''How the Other Half Lives''. Riis believed that potential of every individual was to achieve happiness. In his ''Making of An American'' (1901) he however wrote: | ||

| + | :"Life, liberty, pursuit of happiness? Wind! says the slum, and the slum is right if we let it be. We cannot get rid of the tenements that shelter two million souls in New York today, but we can set about making them at least as nearly fit to harbor human souls as might be." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Riis’s ''How the Other Half Lives'' was directly responsible for convincing then-Commissioner of Police [[Theodore Roosevelt]] to close the police-run poor houses. After reading it, Roosevelt was so deeply moved by Riis's sense of justice that he met Riis and befriended him for life, calling him "the best American I ever knew." Roosevelt himself coined the term "[[Muckraker|muckraking journalism]]," of which Riis is a recognized example, in 1906. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Later life=== | ||

| + | In 1905, Riis’s wife grew ill and died. In 1907, he remarried, and with his new wife Mary Phillips, moved to a farm in Barre, [[Massachusetts]]. Riis's children came from this marriage. | ||

| − | + | Riis died on May 26, 1914, at his Massachusetts farm. His second wife would live until 1967, continuing work on the farm, working on [[Wall Street]] and teaching classes at [[Columbia University]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

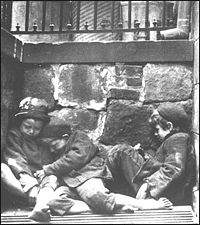

[[Image:Riischildren.jpg|thumb|right|200 px|Children sleeping in Mulberry Street (1890)]] | [[Image:Riischildren.jpg|thumb|right|200 px|Children sleeping in Mulberry Street (1890)]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Criticism=== | |

| + | Contemporary critics have noted that, despite Riis's sense of populist [[justice]], he had a deprecating attitude towards women and people of certain [[ethnicity|ethnic]] and [[race|racial]] groups. In his [[autobiography]], ''The Making of an American'', Riis decided to allow his wife to add a chapter examining her own life. After letting her begin an honest and evocative biographical sketch over several pages titled "Elisabeth Tells Her Story," Riis cut half of her story, saying: "...it is not good for woman to allow her to say too much". | ||

| − | + | Furthermore, Riis's writings revealed his prejudices against certain ethnic groups, cataloguing stereotypes of those with whom he had less in common ethnically. Riis’ middle class and [[Protestant]] backgrounds weighed heavily in his presentation of ''How the Other Half Lives''. Both instilled a strong capitalist idealism; while he pitied certain poor examined as worthy, many others he viewed with contempt. According to Riis, certain races were doomed to failure, as certain lifestyles caused families’ hardships. An example of Riis's ubiquitous ethnic stereotyping is seen in his analysis of how various immigrant groups master the [[English language]]: "Unlike the German, who begins learning English the day he lands as a matter of duty, or the Polish Jew, who takes it up as soon as he is able as an investment, the Italian learns slowly, if at all (''How the Other Half Lives'', 1890). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | |||

| − | + | Jacob Riis was a [[reporter]], a [[photography|photographer]] and a reformer, whose work initiated reforms toward better living conditions for the thousands of people living in poor houses in New York City slums. His [[photography]], taken up to help him document his story, became an important tool in his fight. With it he became important figure in the history of [[documentary photography]]. | |

| − | + | Numerous memorials around [[New York City]] carry Riis’s name. Among others, Jacob Riis Park and Jacob Riis Triangle, both located in [[Queens]], are named after him. The Jacob August Riis School, a New York City public school in [[Manhattan]]'s Lower East Side is also named after Riis. Jacob Riis Settlement House, a multi-service community based organization, is located in the Queensbridge Houses, in Long Island City, Queens, NY. | |

| − | + | ==Publications== | |

| − | + | * Riis, Jacob A. 1909. ''The Old Town''. New York: Macmillan Co | |

| − | + | * Riis, Jacob A. 1914. ''Neighbors: Life Stories of the Other Half''. New York: The Macmillan Company | |

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 1969 (original published 1900). ''A Ten Years' War: An account of the battle with the slum in New York''. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 0836951557 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 1970 (original published 1896). ''Out of Mulberry street''. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Literature House. ISBN 0839817584 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 1971 (original published 1892). ''The Children of the Poor''. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 0405031246 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 1998 (original published 1902). ''The Battle with the Slum''. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486401960 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1890). ''How The Other Half Lives''. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0393930262 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1901). ''The Making of an American''. Echo Library. ISBN 1406839086 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1902). ''Children of the Tenements''. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0548285454 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1903). ''The Peril and the Preservation of the Home''. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0548259801 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1904). ''Theodore Roosevelt, the Citizen''. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0548049769 | ||

| + | * Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1910). ''Hero Tales of the Far North''. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 143462319X | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Davidson, James and Lytle, Mark. 1982. ''After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection''. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0394523229 | ||

| + | * Bernstein, Len. 2001. What Do the World and People Deserve? ''Photographica World, 98''. Retrieved on November 25, 2007, from <http://www.lenbernstein.com/Pages/RiisArticle.html> | ||

| + | * Gandal, Keith. 1997. ''The virtues of the vicious: Jacob Riis, Stephen Crane, and the spectacle of the slum''. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195110633 | ||

| + | * Lane, James B. 1974. ''Jacob A. Riis and the American city''. Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press. ISBN 0804690588 | ||

| + | * Pascal, Janet B. 2005. ''Jacob Riis''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195145275 | ||

| + | * Sandler, Martin W. 2005. ''America through the lens photographers who changed the nation''. New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0805073671 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | * [http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/immigration/people_riis.html Jacob Riis page] from the Open Collections Program at Harvard University | + | * [http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/title.html ''How the Other Half Lives''] - Complete online edition of Riis’s book |

| − | * | + | * [http://www.richmondhillhistory.org/jriis.html Jacob Riis] – Biography and photos on Richmond Hill Historical Society website |

| − | + | * [http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/immigration/people_riis.html Jacob Riis page] from the Open Collections Program at Harvard University, with links to fully digitized copies of 10 of his books. | |

| − | * [http://lenbernstein.com/Pages/RiisArticle.html What Do | + | * [http://www.masters-of-photography.com/R/riis/riis.html Riis’s photographs] on Masters-of-Photography website |

| + | * [http://lenbernstein.com/Pages/RiisArticle.html ''What Do the World and People Deserve?''] - Article on the Life and Work of Jacob Riis | ||

{{Credits|Jacob_Riis|139762604|}} | {{Credits|Jacob_Riis|139762604|}} | ||

Revision as of 02:56, 28 November 2007

Jacob August Riis (May 3, 1849 - May 26, 1914), was a Danish-born American muckraker journalist, photographer, and social reformer. He is known for his dedication to using his photographic and journalistic talents to help the less fortunate in New York City, which was the subject of most of his prolific writings and photographic essays. As one of the first photographers to use flash, he is considered a pioneer in photography.

Biography

Early life

Jacob Riis was born in Ribe, Denmark, the third of fifteen children of Niels Riis, schoolteacher and editor of the local newspaper, and Carolina Riis, a homemaker. Riis was influenced both by his stern father and by the authors he read, among whom Charles Dickens and James Fenimore Cooper were his favorites. At age eleven, Riis's younger brother drowned. Riis would be haunted for the rest of his life by the images of his drowning brother and of his mother staring at his brother's empty chair at the dinner table. At twelve, Riis amazed all who knew him when he donated all the money he received for Christmas to a poor Ribe family, at a time when money was scarce for anyone. When Riis was sixteen, he fell in love with Elisabeth Gortz, but was rejected. He moved to Copenhagen in dismay, seeking work as a carpenter.

Immigration to the United States

Riis came to the United States in 1870, when he was 21, seeking employment as a carpenter. He arrived during an era of social turmoil. Large groups of migrants and immigrants flooded urban areas in the years following the Civil War seeking prosperity in a more industrialized environment. Twenty-four million people moved to urban centers, causing a population increase of over 700%.

The demographics of American urban centers grew significantly more heterogeneous as immigrant groups arrived in waves, creating ethnic enclaves often more populous than even the largest cities in the homelands. Riis found himself just another poor immigrant in New York City. His only companion was a stray dog he met shortly after his arrival. The dog brought him inspiration and when a police officer mercilessly beat it to death, Riis was devastated. One of his personal victories, he later confessed, was not using his eventual fame to ruin the career of the offending officer. Riis spent most of his nights in police-run poor houses, whose conditions were so ghastly that Riis dedicated himself to having them shut down.

At the age of 25, Riis wrote to Elisabeth Gortz to propose a second time. This time Gortz accepted, and joined Riis in New York City. She was a great support in his work.

Journalist career

Riis held various jobs before he accepted a position as a police reporter in 1873 with the New York Evening Sun newspaper. In 1874, he joined the news bureau of the Brooklyn News, working there for 3 years. In 1877, he became a police reporter, this time for the New York Tribune. During these stints as a police reporter, Riis worked the most crime-ridden and impoverished slums of the city. Through his own experience in the poor houses, and witnessing the conditions of the poor in the city slums, he decided to make a difference for those who had no voice.

Riis was one of the first photographers in United States to use flash powder, allowing his documentation of New York City slums to penetrate the dark of night, and helping him capture the hardships faced by the poor, especially on the notorious Mulberry Street. In 1889, Scribner's Magazine published Riis's photographic essay on city life, which Riis later expanded to create his magnum opus How the Other Half Lives. Riis believed that potential of every individual was to achieve happiness. In his Making of An American (1901) he however wrote:

- "Life, liberty, pursuit of happiness? Wind! says the slum, and the slum is right if we let it be. We cannot get rid of the tenements that shelter two million souls in New York today, but we can set about making them at least as nearly fit to harbor human souls as might be."

Riis’s How the Other Half Lives was directly responsible for convincing then-Commissioner of Police Theodore Roosevelt to close the police-run poor houses. After reading it, Roosevelt was so deeply moved by Riis's sense of justice that he met Riis and befriended him for life, calling him "the best American I ever knew." Roosevelt himself coined the term "muckraking journalism," of which Riis is a recognized example, in 1906.

Later life

In 1905, Riis’s wife grew ill and died. In 1907, he remarried, and with his new wife Mary Phillips, moved to a farm in Barre, Massachusetts. Riis's children came from this marriage.

Riis died on May 26, 1914, at his Massachusetts farm. His second wife would live until 1967, continuing work on the farm, working on Wall Street and teaching classes at Columbia University.

Criticism

Contemporary critics have noted that, despite Riis's sense of populist justice, he had a deprecating attitude towards women and people of certain ethnic and racial groups. In his autobiography, The Making of an American, Riis decided to allow his wife to add a chapter examining her own life. After letting her begin an honest and evocative biographical sketch over several pages titled "Elisabeth Tells Her Story," Riis cut half of her story, saying: "...it is not good for woman to allow her to say too much".

Furthermore, Riis's writings revealed his prejudices against certain ethnic groups, cataloguing stereotypes of those with whom he had less in common ethnically. Riis’ middle class and Protestant backgrounds weighed heavily in his presentation of How the Other Half Lives. Both instilled a strong capitalist idealism; while he pitied certain poor examined as worthy, many others he viewed with contempt. According to Riis, certain races were doomed to failure, as certain lifestyles caused families’ hardships. An example of Riis's ubiquitous ethnic stereotyping is seen in his analysis of how various immigrant groups master the English language: "Unlike the German, who begins learning English the day he lands as a matter of duty, or the Polish Jew, who takes it up as soon as he is able as an investment, the Italian learns slowly, if at all (How the Other Half Lives, 1890).

Legacy

Jacob Riis was a reporter, a photographer and a reformer, whose work initiated reforms toward better living conditions for the thousands of people living in poor houses in New York City slums. His photography, taken up to help him document his story, became an important tool in his fight. With it he became important figure in the history of documentary photography.

Numerous memorials around New York City carry Riis’s name. Among others, Jacob Riis Park and Jacob Riis Triangle, both located in Queens, are named after him. The Jacob August Riis School, a New York City public school in Manhattan's Lower East Side is also named after Riis. Jacob Riis Settlement House, a multi-service community based organization, is located in the Queensbridge Houses, in Long Island City, Queens, NY.

Publications

- Riis, Jacob A. 1909. The Old Town. New York: Macmillan Co

- Riis, Jacob A. 1914. Neighbors: Life Stories of the Other Half. New York: The Macmillan Company

- Riis, Jacob A. 1969 (original published 1900). A Ten Years' War: An account of the battle with the slum in New York. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 0836951557

- Riis, Jacob A. 1970 (original published 1896). Out of Mulberry street. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Literature House. ISBN 0839817584

- Riis, Jacob A. 1971 (original published 1892). The Children of the Poor. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 0405031246

- Riis, Jacob A. 1998 (original published 1902). The Battle with the Slum. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486401960

- Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1890). How The Other Half Lives. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0393930262

- Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1901). The Making of an American. Echo Library. ISBN 1406839086

- Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1902). Children of the Tenements. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0548285454

- Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1903). The Peril and the Preservation of the Home. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0548259801

- Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1904). Theodore Roosevelt, the Citizen. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0548049769

- Riis, Jacob A. 2007 (original published 1910). Hero Tales of the Far North. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 143462319X

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Davidson, James and Lytle, Mark. 1982. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0394523229

- Bernstein, Len. 2001. What Do the World and People Deserve? Photographica World, 98. Retrieved on November 25, 2007, from <http://www.lenbernstein.com/Pages/RiisArticle.html>

- Gandal, Keith. 1997. The virtues of the vicious: Jacob Riis, Stephen Crane, and the spectacle of the slum. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195110633

- Lane, James B. 1974. Jacob A. Riis and the American city. Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press. ISBN 0804690588

- Pascal, Janet B. 2005. Jacob Riis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195145275

- Sandler, Martin W. 2005. America through the lens photographers who changed the nation. New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0805073671

External links

- How the Other Half Lives - Complete online edition of Riis’s book

- Jacob Riis – Biography and photos on Richmond Hill Historical Society website

- Jacob Riis page from the Open Collections Program at Harvard University, with links to fully digitized copies of 10 of his books.

- Riis’s photographs on Masters-of-Photography website

- What Do the World and People Deserve? - Article on the Life and Work of Jacob Riis

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.