Difference between revisions of "Heloise" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

::I love you more than ever; and so revenge myself on him (Fulbert). I will still love you with all the tenderness of my soul till the last moment of my life. If, formerly, my affection for you was not so pure, if in those days both mind and body loved you, I often told you even then that I was more pleased with possessing your heart than with any other happiness, and the man was the thing I least valued in you. (Gollancz, pg. 30) | ::I love you more than ever; and so revenge myself on him (Fulbert). I will still love you with all the tenderness of my soul till the last moment of my life. If, formerly, my affection for you was not so pure, if in those days both mind and body loved you, I often told you even then that I was more pleased with possessing your heart than with any other happiness, and the man was the thing I least valued in you. (Gollancz, pg. 30) | ||

| − | == | + | ==Separate lives== |

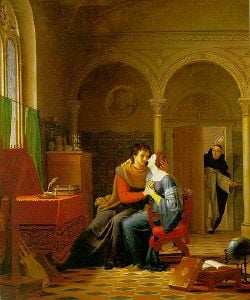

[[Image:Angelica Kauffmann 001.jpg|thumb|350px|left| Abelard and Heloise by [Angelica Kauffmann]]] | [[Image:Angelica Kauffmann 001.jpg|thumb|350px|left| Abelard and Heloise by [Angelica Kauffmann]]] | ||

| + | [[Abelard]] took vows as a monk and left public life. He asked Heloïse to enter a convent and likwise take vows. She protested, but he insisted. Perhaps he feared that she would marry someone else. He insisted that he would henceforth relate to her only as the "beloved of Christ." | ||

| − | Abelard | + | In 1121, Abelard's intellectual rivals pushed to have his book on the Holy Trinity condemned. A Church council at Soissons did so and Abelard was forced to become a monk. His time at the royal abbey of [[St. Denis]] near Paris was contention regardless of Abelard's fame, his contentious attitude and denial of the miraculous events that founded the abbey caused him to found a new religious community, which he called the Paraclete, fifty miles north of Paris. |

| − | + | Later, Abbot Suger, of St. Denis took over the control of the old women's monastery of Argenteuil, where Heloïse was abbess, and expelled all the women. Heloïse and her nuns, to whom she was probably teaching Abelard's doctrines, were without a home. Abelard invited them to the Paraclete and turned it over to Heloïse and he moved to St. Gildas in Brittany, but the monks there hated him so he accused them of trying to poison him. | |

| − | + | It was at about this time that a correspondence between the two former lovers sprang up. Heloïse encouraged Abélard in his philosophical work, and he dedicated his profession of faith to her. Heloïse lamented her loss of Abelard's love, both sexual, and intellectual or spiritual. | |

| − | |||

| − | It was at about this time that a correspondence between the two former lovers sprang up. Heloïse encouraged Abélard in his philosophical work, and he dedicated his profession of faith to her. Heloïse lamented her loss of Abelard's love, both sexual and intellectual or spiritual. | ||

Heloïse first reads the ''Historia'' he had sent to a friend, she complains he should have written it to her as she is his wife and needs his company and asks him to move to the Paraclete and live with her. | Heloïse first reads the ''Historia'' he had sent to a friend, she complains he should have written it to her as she is his wife and needs his company and asks him to move to the Paraclete and live with her. | ||

| Line 100: | Line 99: | ||

==Contributions to Women's Monastic Life== | ==Contributions to Women's Monastic Life== | ||

| − | The Rule of Benedict, concerning monastic life, had lasted throughout the centuries and had been adequate for the lives of men, but women's bodies were different with physical needs that were not covered in the Rule | + | Heloise had an urgent need to reform monastic life to accommodate the new and expanding community of women. The Rule of Benedict, concerning monastic life, had lasted throughout the centuries and had been adequate for the lives of men, but women's bodies were different with physical needs that were not covered in the Rule. |

| − | The ''Problemata | + | The ''Problemata'' (Heloïse's Problems) are a collection of 42 theological questions directed from Heloise to Abelard at the time when she was abbess at the Paraclete, and his answers to them. From this discourse came a Rule that allowed Heloïse to guide her women's abbey and establish a standard for all other abbeys. Abelard established a standard of dress, which Heloïse adjusted, it included a chemise dress of lamb's skin, a robe, sandals, a veil with a rope girdle and a mantle in the winter. Nuns slept in their habits and at Heloïse's insistence "to keep vermin away," they had two sets of clothes. |

| − | Their diet consisted of mostly vegetables, they ate no meat | + | Their diet consisted of mostly vegetables, and they ate no meat. Wine was used only for the ill. Those who ventured out of the monastery were punished with a diet of bread and water only isolated in their room for a day. Any woman who violated her vow of chastity never could wear the veil again after she was severely beaten. Her questions led to a rule that governed all aspects of life for the women living in the monastery. She even asks, "Is it proper for us nuns never to extend hospitality to men?" |

| − | + | The''Problemata'' not only produced a Rule for the women's monastery, but also reesulted in Heloise applying Abelard's innovative method of approaching questions. This style of dialectic became a model for education that she maintained in her spiritual community. Thus, his spirit lived on in the intense study in which every woman at the Paraclete was required to participate. | |

| − | For | + | For 20 years after the death of Abelard she successfully ran the Paraclete and maintained good relations with the other male-run monasteries, political leaders, and even Abelard's enemy [[Bernard of Clairvaux]]. Heloise also established six sister abbeys around Paris. |

| − | == | + | ==Burial== |

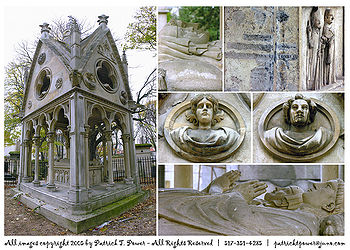

| − | + | [[Image:AbelardHeloiseTomb.jpg|thumb|left|350px|Composite image of the tomb of Abélard et Héloïse.]] | |

| + | Heloise's actual resting place is a question of controversy. | ||

| − | + | Abelard's body was brought from [[Cluny]] to the Paraclete at Heloïse's request. She was buried there with him. They were then moved to a local church of Saint-Laurent at Nogent-sur-Seine. In 1804 their bones were brought to the gardens of the [[Elysee in Paris]], where [[Napoleon]] and [[Josephine]] paid tribute to their shrine. In 1817 their final resting place became Père-Lachaise cemetery where, upon their raised tomb, two full-length figures of a monk and a nun rest atop the sarcophagus. A Gothic-revival enclosure protects them from sun and possible damage. The American musician, [[Jim Morrison]], is buried nearby. | |

| − | The | + | The Oratory of the Paraclete, however, claims Heloise and Abélard are still buried at the Paraclete and that what exists in Père-Lachaise is merely a monument. There are still others who believe that while Abélard is buried in the crypt at Père-Lachaise, Heloïse's remains are elsewhere. |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| − | + | In the obituary created by her nuns, Heloïse was called their "brilliant mother." Her pioneer contributions to the Rule guiding the lives of nuns set the standard for all nunneries and lasted until the [[French Revolution]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In recent years, as scholars sift through history looking for women of note to balance the male-dominated record, Heloïse has been rediscovered. Not only has Heloïse the lover come into sharper fouce, but Heloïse the leader has emerged more clearly as a woman of power and insight, especially after Abelard's death. | |

| − | + | The personal letters of Heloise and Abelard were discovered in the Paraclete and translated into French by Jean de Meun, a Parisian cleric. His book ''The Romance of the Rose'', shows an unusual support for Heloïse's tragic story, which he saw as profoundly moral. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Abelard | + | The story of Abelard and Heloïse captured the imagination of many throughout history. Chaucer knew of their story; Alexander Pope wrote ''Eloisa to Abelard'' in 1717; Rousseau composed ''La Nouvelle Heloise''; and Mark Twain wrote about Heloïse's "self-sacrificing love," although he said this wasn't "good sense". |

| − | The | + | The love story of Abelard and Heloïse also inspired the poem "The Convent Threshold" by the Victorian English poet [[Christina Rossetti]]. The play ''Peter Abelard'' which was adapted from Waddell's novel, was performed on stage in the late 1960s where a sometimes nude, Diana Rigg, played Heloïse. In 2002 this play became an opera in New York. The 2004 movie entitled, ''Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind'', starring [[Jim Carey]] and [[Kate Winslet]], takes it's title from the 1557 epistle by [[Alexander Pope]], ''Eloisa to Abelard''. [[Howard Brenton]]'s play ''[[In Extremis|In Extremis: The Story of Abelard and Heloise]]'' premiered at [[Shakespeare's Globe]] in 2006. |

==Footnotes== | ==Footnotes== | ||

Revision as of 03:29, 11 May 2007

The letters of Heloïse (1101-1162) and Pierre Abélard are among the best known records of early romantic love.

Though Heloïse (also spelled Héloise, Hélose, Heloisa, and Helouisa, among other variations) is best known for her relationship with Peter Abélard, she was a brilliant scholar of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew and had a reputation for intelligence and insight. Not a great deal is known of her immediate family except that in her letters she implies she is of a lower social standing (probably the Garlande family who had money and several family members in strong social and political positions) than was Abélard, who was from the nobility.

What is known is that she was the ward of an uncle, a canon in Paris named Fulbert, and by the age of 18 she had become the student of Pierre Abélard who was one of the most popular teachers and philosophers in Paris.

In his writings, Abélard tells the story of his seduction of Heloïse, the birth of a son, Astrolabius (in English, "Astrolabe"), their subsequent marriage, and their attempts to keep it secret to protect his reputation, as she lived with her uncle, and of his castration by her furious guardian when he thought Abelard had abandoned her, after which Heloïse entered a convent in Argenteuil at Abelard's urging.

At the convent in Argenteuil, Heloïse eventually became prioress. She and the other nuns were turned out when the convent was taken over, at which point Abélard arranged for them to enter the Oratory of the Paraclete, an abbey he had established, and Heloïse became the abbess there. It is from here that her contributions to monastic life for women were made. The story of Heloise can only be told within the context of her love relationship with Abelard.

Early Life

Heloïse was probably raised in the nunnery of Argenteuil, where her mother, Hersinde, lived. There is no record of her father or of her birth. Her mother could have been married, a widow, a formal concubine, or simply an unwed mother. In this period, many wealthy women chose to live in monasteries, where they could receive education, while other institutional structures increasingly denied them this opportunity up until the late nineteenth century.

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, male primogeniture was established. This allowed the eldest son to inherit all the property instead of cutting it up among all the offspring including girls, thus keeping it intact for the family. Other sons were then sent off to soldiering or scholarship or monastic life, daughters were married off or sent to a nunnery.

The extent of Heloïse's education is uncertain, but even in her youth she was considered a "rara avis." Her fame was already known before she moved to Paris, and this is one of the attractions that brought Abelard to arrange to become her tutor. From Heloïse's letters we can see that she was well versed in the secular Latin poets and the classical philosophical traditions. She loved Cicero and Latin rhetoric, and deeply loved the fourth century Church father St. Jerome.

Seduction by Abelard

In 1116 Heloïse left the abbey in Argenteuil and moved to the home of her uncle, Fulbert. He lived very near St. Etienne, which was later replaced by the Cathedral of Notre Dame. It was in her uncle's home that her life began its most famous episode.

Abelard was the most popular philosopher and teacher in Paris, he was respected above all others and many flocked to hear his lectures at the cathedral school of Paris .

Abelard had heard of Heloïse before he met her; he wrote: "A gift for letters is so rare in women that it added greatly to her charm and had won her renown throughout the realm" (Radice, p.66). Abelard tells in his Historica clamitatum (The Story of My Calamity), that his pride led to experiment with sexual subjects. He laid a plan to become Heloise's tutor and seduce her. He arranged to actually move into the home of Canon Fulbert, claiming that his own home was too noisy.

Abelard writes about the development of affair with Heloise:

- Her studies allowed us to withdraw in private, as love desired, and then with our books open before us, more words of love than of reading passed between us, and more kissing than teaching. My hands strayed oftener to her bosom than to the pages; love drew our eyes to look on each other more than reading kept them on our texts. (Gollancz, Historica clamitatum:a letter to his friend Philintus, pg. 9)

When Heloïse became pregnant, Abelard fled with her to his family home where he intended to marry her, overcoming her protests that their marriage, unnecessary to her, would ruin his reputation. His work, in her mind, was far more important than her life and pregnancy. Heloïse saw most contemporary marriages as distasteful commercial transactions. She argued that the daily family life was a burden, noisy, costly, and dirty.

Abelard returned to Paris with her and did in fact marry her, with her uncle present, having left their son to be raised by Abelard's family. She lived for a time with her uncle, trying to keep the marriage a secret. Abelard visited her in her uncle's home. This arrangement, however, did not placate her uncle's sense of dishonor, nor was it kept secret. Fulbert "heaped abuse on her on several occasions," and she followed Abelard's instruction to go back to Argenteuil as a lay guest, instead of living with him openly as his wife or mistress in Paris.

Abelard's castration

When Heloïse moved to the abbey in Argenteuil, her uncle, believing that Abelard had abandoned her in shame, became vengefully furious and had Abelard castrated as he slept in his bed. The castration was scandalous, and as arestul, Abelard removed himself from public life in shame. Heloise felt robbed of the most important thing in her life, for her love for Abelard had been complete, her dedication absolute:

- I love you more than ever; and so revenge myself on him (Fulbert). I will still love you with all the tenderness of my soul till the last moment of my life. If, formerly, my affection for you was not so pure, if in those days both mind and body loved you, I often told you even then that I was more pleased with possessing your heart than with any other happiness, and the man was the thing I least valued in you. (Gollancz, pg. 30)

Separate lives

Abelard took vows as a monk and left public life. He asked Heloïse to enter a convent and likwise take vows. She protested, but he insisted. Perhaps he feared that she would marry someone else. He insisted that he would henceforth relate to her only as the "beloved of Christ."

In 1121, Abelard's intellectual rivals pushed to have his book on the Holy Trinity condemned. A Church council at Soissons did so and Abelard was forced to become a monk. His time at the royal abbey of St. Denis near Paris was contention regardless of Abelard's fame, his contentious attitude and denial of the miraculous events that founded the abbey caused him to found a new religious community, which he called the Paraclete, fifty miles north of Paris.

Later, Abbot Suger, of St. Denis took over the control of the old women's monastery of Argenteuil, where Heloïse was abbess, and expelled all the women. Heloïse and her nuns, to whom she was probably teaching Abelard's doctrines, were without a home. Abelard invited them to the Paraclete and turned it over to Heloïse and he moved to St. Gildas in Brittany, but the monks there hated him so he accused them of trying to poison him.

It was at about this time that a correspondence between the two former lovers sprang up. Heloïse encouraged Abélard in his philosophical work, and he dedicated his profession of faith to her. Heloïse lamented her loss of Abelard's love, both sexual, and intellectual or spiritual.

Heloïse first reads the Historia he had sent to a friend, she complains he should have written it to her as she is his wife and needs his company and asks him to move to the Paraclete and live with her.

But he replies that it would be scandalous and they are no longer married. Her letter disagrees with his argument, his reply counters her argument again. These two letters reveal their ideas of guilt and the danger that women pose to great men. Heloïse is even more adamant than Abelard about the dangers of women, pointing to the guilt she feels at his sorry state.

Their Struggle to Accept Their Fate

Their struggle to accept their forced separation and efforts to find devotion to the monastic life was clearly revealed in their eloquent letters to each other.

Abelard writes to Heloïse:

- If my passion has been put under a restraint my thoughts yet run free. I promise myself that I will forget you, and yet cannot think of it without loving you. My love is not at all lessened by those reflections I make in order to free myself. The silence I am surrounded by makes me more sensible to its impressions, and while I am unemployed with any other things, this makes itself the business of my whole vacation. Till after a multitude of useless endeavors I begin to persuade myself that it is a superfluous trouble to strive to free myself; and that it is sufficient wisdom to conceal from all but you how confused and weak I am.

Heloïse wrote to Abelard:

- Even during the celebration of Mass, when our prayers should be purer, lewd visions of those pleasures take such a hold upon my unhappy soul that my thoughts are on their wantonness instead of on prayers...

- God is my witness that if Augustus, Emperor of the whole world, thought fit to honor me with marriage and conferred all the earth on me to possess forever, it would be dearer and more honorable to me to be called not his Empress but your whore. (Gollancz, pp. 51-52)

Abelard answered Heloïse's first letter, writing that there was no reason to see each other. He implied that their marital love should now be transformed into a love of God. Heloïse's second letter strongly disagrees:

- But if I lose you what is left for me to hope for? What reason for continuing on life's pilgrimage, for which I have no support but you, and none in you save the knowledge that you are alive, now that I am forbidden all other pleasures in you and denied even the joy of your presence which from time to time could restore me to myself?...

- I do not wish you to exhort me to virtue or summon me to battle. You say, "Power comes to its full strength in weakness" and "He cannot win a crown unless he has kept the rules." I do not seek a crown of victory; it is sufficient for me to avoid danger, and this is safer than engaging in war. In whatever corner of heaven God shall place me, it will be enough for me. No one will envy another there, and what each one has will suffice. (pp. 65, 69-71)

Abelard's reply to Heloïse's second letter told her to stop complaining:

- "I had thought that this bitterness of heart... had long since disappeared.... If you are anxious to please me in everything, as you claim,... you must rid yourself of it. If it persists you can neither please me nor attain bliss with me" (p. 79).

Heloïse obeyed her husband. She wrote a third letter in which after the opening, she spoke only in request as an abbess for specific guidance for a practical Rule to guide the life of the nuns under her care. During this time Abelard was excommunicated and his books were ordered burned. Perhaps Heloïse meant to keep his ideas alive by drawing his philosophy out in letters to her. In this way his teachings could remain at least in the records of the Paraclete. Her third letter opens:

- I would not want to give you cause for finding me disobedient in anything, so I have set the bridle of your injunction on the words which issue from my unbounded grief; thus in writing at least I may moderate what it is difficult or rather impossible to forestall in speech. For nothing is less under our control than the heart --- having no power to command it we are forced to obey. And so when its impulses move us, none of us can stop their sudden promptings from easily breaking out, and even more easily overflowing into words which are the ever-ready indications of the heart's emotions....

- I will therefore hold my hand from writing words which I cannot restrain my tongue from speaking; would that a grieving heart would be as ready to obey as a writer's hand.

- And yet you have it in your power to remedy my grief, even if you cannot entirely remove it. As one nail drives out another hammered in, a new thought expels an old, when the mind is intent on other things and forced to dismiss or interrupt its recollection of the past....

- And so all we handmaids of Christ, who are your daughters in Christ, come as suppliants to demand of your paternal interest two things which we see to be very necessary for ourselves. One is that you will tell us how the order of nuns began and what authority there is for our profession. The other, that you will prescribe some Rule for us and write it down, a Rule which shall be suitable for women....(pp. 93-94)

In the end Abelard agrees to write a rule for her nuns, some letters of spiritual and institutional direction and ninety three hymns for a year-long liturgy. This sealed their final relationship of monk and abbess.

Historian Constant Mews's work, The Lost Love Letters of Heloise and Abelard, is a set of 113 anonymous love letters found in a fifteenth century manuscript in the Paraclete which represent the correspondence exchanged by Héloïse and Abélard during the earlier phase of their relationship. This series of letters and the entire exchange between the two lovers is remarkable in history, a first person account of the joy and sadness of their love and the evolution of their personal love to the spiritual.

Contributions to Women's Monastic Life

Heloise had an urgent need to reform monastic life to accommodate the new and expanding community of women. The Rule of Benedict, concerning monastic life, had lasted throughout the centuries and had been adequate for the lives of men, but women's bodies were different with physical needs that were not covered in the Rule.

The Problemata (Heloïse's Problems) are a collection of 42 theological questions directed from Heloise to Abelard at the time when she was abbess at the Paraclete, and his answers to them. From this discourse came a Rule that allowed Heloïse to guide her women's abbey and establish a standard for all other abbeys. Abelard established a standard of dress, which Heloïse adjusted, it included a chemise dress of lamb's skin, a robe, sandals, a veil with a rope girdle and a mantle in the winter. Nuns slept in their habits and at Heloïse's insistence "to keep vermin away," they had two sets of clothes.

Their diet consisted of mostly vegetables, and they ate no meat. Wine was used only for the ill. Those who ventured out of the monastery were punished with a diet of bread and water only isolated in their room for a day. Any woman who violated her vow of chastity never could wear the veil again after she was severely beaten. Her questions led to a rule that governed all aspects of life for the women living in the monastery. She even asks, "Is it proper for us nuns never to extend hospitality to men?"

TheProblemata not only produced a Rule for the women's monastery, but also reesulted in Heloise applying Abelard's innovative method of approaching questions. This style of dialectic became a model for education that she maintained in her spiritual community. Thus, his spirit lived on in the intense study in which every woman at the Paraclete was required to participate.

For 20 years after the death of Abelard she successfully ran the Paraclete and maintained good relations with the other male-run monasteries, political leaders, and even Abelard's enemy Bernard of Clairvaux. Heloise also established six sister abbeys around Paris.

Burial

Heloise's actual resting place is a question of controversy.

Abelard's body was brought from Cluny to the Paraclete at Heloïse's request. She was buried there with him. They were then moved to a local church of Saint-Laurent at Nogent-sur-Seine. In 1804 their bones were brought to the gardens of the Elysee in Paris, where Napoleon and Josephine paid tribute to their shrine. In 1817 their final resting place became Père-Lachaise cemetery where, upon their raised tomb, two full-length figures of a monk and a nun rest atop the sarcophagus. A Gothic-revival enclosure protects them from sun and possible damage. The American musician, Jim Morrison, is buried nearby.

The Oratory of the Paraclete, however, claims Heloise and Abélard are still buried at the Paraclete and that what exists in Père-Lachaise is merely a monument. There are still others who believe that while Abélard is buried in the crypt at Père-Lachaise, Heloïse's remains are elsewhere.

Legacy

In the obituary created by her nuns, Heloïse was called their "brilliant mother." Her pioneer contributions to the Rule guiding the lives of nuns set the standard for all nunneries and lasted until the French Revolution.

In recent years, as scholars sift through history looking for women of note to balance the male-dominated record, Heloïse has been rediscovered. Not only has Heloïse the lover come into sharper fouce, but Heloïse the leader has emerged more clearly as a woman of power and insight, especially after Abelard's death.

The personal letters of Heloise and Abelard were discovered in the Paraclete and translated into French by Jean de Meun, a Parisian cleric. His book The Romance of the Rose, shows an unusual support for Heloïse's tragic story, which he saw as profoundly moral.

The story of Abelard and Heloïse captured the imagination of many throughout history. Chaucer knew of their story; Alexander Pope wrote Eloisa to Abelard in 1717; Rousseau composed La Nouvelle Heloise; and Mark Twain wrote about Heloïse's "self-sacrificing love," although he said this wasn't "good sense".

The love story of Abelard and Heloïse also inspired the poem "The Convent Threshold" by the Victorian English poet Christina Rossetti. The play Peter Abelard which was adapted from Waddell's novel, was performed on stage in the late 1960s where a sometimes nude, Diana Rigg, played Heloïse. In 2002 this play became an opera in New York. The 2004 movie entitled, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, starring Jim Carey and Kate Winslet, takes it's title from the 1557 epistle by Alexander Pope, Eloisa to Abelard. Howard Brenton's play In Extremis: The Story of Abelard and Heloise premiered at Shakespeare's Globe in 2006.

Footnotes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burge, James. Heloise & Abelard: A New Biography (Plus). HarpersSanFrancisco, 2006. ISBN 978-0060816131

- Clanchy, Michael, Betty Radice, trans. The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. Penguin Classics; Revised edition, 2004. ISBN 978-0140448993

- Dronke, Peter. Abelard and Heloise in Medieval Testimonies. Glasgow; University of Glasgow Press, 1976.

- Gollancz, Israel, and Honnor Morten, ed. (anonymous translation). The Love Letters of Abelard and Heloise, (first French translation ed. 1616), J.M. Dent & co.; Aldine House, London. 1901. At www.sacred-texts.com.

- Mews, Constant J., Neville Chiavaroli, trans. The Lost Love Letters of Heloise and Abelard: Perceptions of Dialog in Twelfth-Century France (The New Middle Ages). Palgrave Macmillan; new ed. 2001. ISBN 978-0312239411

- Wheeler, Prof. Bonnie. Medieval Heroines in History and Legend. The Teaching Company, 2002. ISBN 1-56585-523-X

External links

- Abelard and Heloise from In Our Time (BBC Radio 4). www.bbc.co.uk Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. www.sacred-texts.com Retrieved May 5, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.