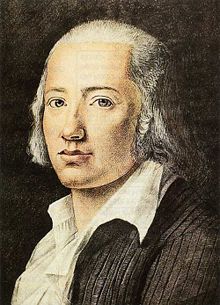

Friedrich Hölderlin

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (March 20, 1770 – June 6, 1843) was a major German lyric poet. His work bridges the Classical and Romantic schools.

Life

Hölderlin was born in Lauffen am Neckar in the kingdom of Württemberg. He studied Theology at the Tübinger Stift seminary, where he was friends and roommates with the future philosophers Georg Hegel and Friedrich Schelling. They mutually influenced one another, and it has been pointed out by some that it was probably Hölderlin who brought to Hegel's attention the ideas of Heraclitus regarding the union of opposites, which the philosopher would develop into his concept of dialectics.

Being from a family of limited means (his mother was twice a widow), and having little inclination for an ecclesiastical career, Hölderlin had to earn his living as a tutor of children of well-to-do families. While working as the tutor of the sons of Jakob Gontard, a Frankfurt banker, he fell in love with his wife Susette, who would become his great love. Susette Gontard is the model for the Diotima of his epistolary novel Hyperion.

Having been publicly insulted by Gontard, Hölderlin felt forced to quit his job in the banker's household and found himself again in a difficult financial situation (even as some of his poems were already being published through the influence of his occasional protector, the poet Friedrich Schiller). He was forced to accept a small allowance from his mother in order to survive.

Already by this time Hölderlin had been diagnosed as suffering from severe "hypochondria", a mental condition that would worsen after his last meeting with Susette Gontard in 1800. In early 1802 he found a job as tutor of the children of the Hamburg consul in Bordeaux, France, and traveled by foot to that city. His travel and stay there are celebrated in Andenken (Remembrance), one of his greatest poems. In a few months, however, he would be back in Germany showing signs of mental disorder, which was aggravated by the news of Susette's death.

In 1807, having become largely insane, he was brought into the home of Ernst Zimmer, a Tübingen carpenter with literary leanings, who was an admirer of his Hyperion. For the next 36 years, Hölderlin would live in Zimmer's house, in a tower room overlooking the beautiful Neckar valley, being cared for by the Zimmer family until his death in 1843. Wilhelm Waiblinger, a young poet and admirer, has left a poignant account of Hölderlin's day-to-day life during these long, empty years.

Work

The poetry of Hölderlin, widely recognized today as one of the highest points of German and Western literature, was quite forgotten very soon after his death. His illness and reclusion made him fade from his contemporaries' consciousness; and, even though selections of his work were being published by his friends during his lifetime, his poetry was largely ignored for the rest of the 19th century, Hölderlin being classified as a mere imitator of Schiller, a romantic and melancholy youth. He would be rediscovered, by Norbert von Hellingrath, only in the early 20th-century. Since his redisocvery, Hölderlin has, like his contemporary William Blake, another poet who was labeled insane and ignored for centuries, rocketed into the highest esteem; he is now viewed by many scholars as one of the most innovative and gifted poets of his generation.

One of the first changes to come about from this rediscovery was a reassesment of Hölderlin's character. For years, many critics had written him off as an idealistic and infirm Romantic who laid in bed all day, either in madness or reverie, completely removed from the concerns of the real world. In actuality, Hölderlin was a man of action and a man of his time. He was an early supporter of the French Revolution – in his youth at the Seminary of Tübingen, he and some colleagues from a "republican club" planted a "Tree of Freedom" in the market square, prompting the Grand-Duke himself to admonish the students at the seminary. He was a great admirer of Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he honors in one of his early couplets (coincidentally, it should be noted that Hölderlin's exact contemporary Beethoven also initially dedicated his Eroica to the Corsican general).

Like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Schiller, his older contemporaries, Hölderlin was a fervent admirer of ancient Greek culture, but had a very personal understanding of it. Much later, Friedrich Nietzsche and his followers would recognize in him the poet who first acknowledged the orphic and dionysiac Greece of the mystery religions. Hölderlin fused these ancient, mysticl traditions with the Pietism of his native Swabia in a highly original religious experience. For Hölderlin, the Greek gods were not the plaster figures of conventional classicism, but living, actual presences, wonderfully life-giving and, at the same time, terrifying. He understood and sympathized with the Greek idea of the tragic fall, which he expressed movingly in the last stanza of his Hyperions Schicksalslied ("Hyperion's Song of Destiny").

In the great poems of his maturity, Hölderlin would generally adopt a large-scale, expansive and unrhymed style. Together with these long hymns and elegies – which included Der Archipelagus ("The Archipelago"), Brot und Wein ("Bread and Wine") and Patmos – he also cultivated a crisper, more concise manner in epigrams and couplets, and in short poems like the famous Hälfte des Lebens ("The Middle of Life"). In his years of madness, he would occasionally pen ingenuous rhymed quatrains, sometimes of a childlike beauty, which he would sign with fantastic names, such as Scardanelli. Some went so far as to claim that his late poems written in the asylum (the so-called "tower poems"), full of "Homeric beauty", were the crystallization of his thoughts, and thus the greatest part of his works. Some have gone as far to suggest that his madness was indeed a voluntary one. Such claims are generally dismissed as romantic exaggeration today, though the critical evaluation of Hölderlin's tower poems continues to expand, with more than a number of poets and critics arguing that, though he may have been insane, Hölderlin's late works herald a style of poetry centuries ahead of its time that prefigures many of the tropes of what would become postmodernism.

Influence

Though Hölderlin's hymnic style – dependent as it is on a genuine belief in the divinity – can hardly be transposed without sounding satirical, his shorter and more fragmentary lyrical poetry has exerted its influence in German poetry, from Georg Trakl onwards, and his elegiac mode has found an apt successor in Rainer Maria Rilke. He also had an influence on the poetry of Herman Hesse.

Hölderlin earned some negative notoriety during his lifetime by his translations of Sophocles, which were considered awkward and contrived. In the 20th century, theorists of translation like Walter Benjamin have vindicated them, showing their importance as a new – and greatly influential – model of poetic translation.

Hölderlin was a poet-thinker who wrote, fragmentarily, on poetic theory and philosophical matters. His theoretical works, such as the essays Das Werden im Vergehen ("Becoming in Dissolution") and Urteil und Sein ("Judgement and Being") are insightful and important if somewhat tortuous and difficult to parse. They raise many of the key problems also addressed by his Tübingen roommates Hegel and Schelling. And, though his poetry was never "theory-driven", the interpretation and exegesis of some of his more difficult poems has given rise to profound philosophical speculation by such divergent thinkers as Martin Heidegger and Theodor Adorno.

External links

- Hölderlin at Books and Writers

- Penguin UK author's page on Hölderlin

- "Friedrich Hölderlin's Life, Poetry and Madness" - 1830 essay by Wilhelm Waiblinger

- "In Pressel’s Garden-house" (.pdf file) - 1913 story by Hermann Hesse about Hölderlin's madness in Tuebingen

- 1911 encyclopedia entry on Hölderlin

- Hölderlin Gesellschaft (in German, links to English, French, Spanish, and Italian)

- Selected Poems of Hölderlin - English translations

- Poems by Friedrich Hölderlin - English translations

- The Ister - the 2004 film

- Tuebingen Hölderlin Clock - novelty item from Hölderlin's Tuebingen

- Complete list of Hölderlin's poems in german

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.