Escherichia coli

| Escherichia coli | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

|

Conservation status: Secure

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Escherichia coli T. Escherich, 1885 |

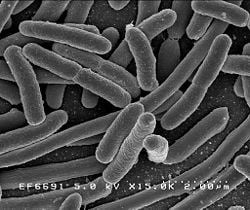

Escherichia coli (IPA: [ˌɛ.ʃəˈɹɪ.kjə ˈkʰoʊ.laɪ]) (E. coli), is one of the well known and significant species of bacteria living as gut flora in the lower intestines of mammals. Since its discovery in 1885 by Theodor Escherich, a German pediatrician and bacteriologist (Feng et al. 2002), E. coli has been the subject of intense research because of its abundance in close association with human beings. The number of individual E. coli bacteria in the feces that a human excretes in one day averages between 100 billion and 10 trillion.[citation needed] For this reason, E. coli has been used in water analysis as the indicator of fecal contamination. However, the bacteria are not confined to this environment, and specimens have also been located, for example, on the edge of hot springs. E. coli is a rod shaped, Gram-negative, facultative anaerob, lactose fermenting, non-endospore forming microorganisms. Its cell measures 1–2 µm in length and 0.1–0.5 µm in diameter. It can survive outside of the host for a while, but the disinfection of all active bacteria can be easily carried out by pasteurization or simple boiling, more rigorous sterilization process is not required.

Strains

A "strain" of E. coli is a group with some particular characteristics that make it distinguishable from other E. coli strains. These differences are often detectable only on the molecular level; however, they may cause changes in the physiology or lifecycle of the bacterium, leading for example, to the different level of pathogenicity. Different strains of E. coli live in different kinds of animals, so it is possible to trace whether the fecal material in water came from humans or from birds, for example. New strains of E. coli arise all the time from the natural biological process of mutation, and some of those strains develop characteristics that can be harmful to their host animal. Although in most healthy adult humans such a strain would probably cause no more than a bout of diarrhea, and might produce no symptoms at all, in young children, people who are or have recently been sick, or in people taking certain medications, such a strain can cause serious illness and even death. A particularly virulent example of such a strain of E. coli is E. coli O157:H7. The E. coli strain O157:H7 is one of hundreds of strains of the bacterium that causes illness in humans.[1]

In addition, E. coli and related bacteria possess the ability to transfer DNA via bacterial conjugation, which allows a new mutation to spread through an existing population. It is believed that this process led to the spread of toxin synthesizing capability from Shigella to E. coli O157:H7. The combination of letters and numbers in the name of the bacterium refers to the specific markers found on its surface and distinguishes it from other strains of E. coli.

Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)–producing E. coli are antibiotic-resistant strains. They produce an enzyme called extended-spectrum beta lactamase, which makes them resistant to antibiotics, thus making the infections harder to treat. In many instances, only few oral antibiotics and a very limited group of intravenous antibiotics remain effective.

Detection of E. coli

As a result of their adaptation to mammalian intestines, E. coli grows best in vivo or at the higher temperatures characteristic of such an environment, rather than the cooler temperatures found in soil and other environments. All the different kinds of fecal coli bacteria (i.e., E. coli), and all the very similar (twin brother) bacteria that live in the soil or decaying plants (of which the most common is Enterobacter aerogenes), are grouped together under the name coliform bacteria. Technically, the "coliform group" is defined to be all the aerobic and facultative anaerobic, non-spore-forming, Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria that ferment lactose with the production of gas within 48 hours at 35°C (95°F). In the body, this gas is released as flatulence. Thus, they are very easily differentiated from others by growing them in lactose-peptone-nutrient medium (e.g., Mac-Conkey broth produced by Merck) at 37°C for 48 hours and checking if they can evolve gas. For further differentiation of the fecal coli, they are grown in lactose-peptone-eosin-methyl blue (EMB) agar medium. After incubating the medium at 37°C for 48 hours, E. coli develop into blue black colonies with light reflecting metallic shine, where as Enterobacter forms reddish slimy colonies.

Causal agent of diseases

"E. coli" can generally cause several intestinal and extra-intestinal infections such as urinary tract infections, meningitis, peritonitis, mastitis, septicemia and gram-negative pneumonia. If E. coli bacteria escape the intestinal tract through a perforation (a hole or tear, for example from an ulcer, a ruptured appendix, or a surgical error) and enter the abdomen, they usually cause peritonitis that can be fatal without prompt treatment.

Urinary tract infections

Although it is more common in females due to the shorter urinary tract, urinary tract infection is seen in both males and females. It is found in roughly equal proportions in elderly men and women. Since bacteria invariably enter the urinary tract through the urethra- called "ASCENDING INFECTIONS", poor toilet habits can predispose to infection (doctors often advise women to "wipe front to back, not back to front") but other factors are also important (pregnancy in women, prostate enlargement in men) and in many cases the initiating event is unclear. While ascending infections are generally the rule for Lower urinary tract infections and cystitis, the same may not necessarily hold for upper Urinary Tract Infections like pyelonephritis which may be hematogenous in origin. Most cases of lower urinary tract infections in females are benign and do not need exhaustive laboratory work ups. However, UTI in young infants must receive some imaging study, typically a retrograde urethrogram, to ascertain the presence/absence of congenital urinary tract anomalies. Males too must be investigated further.

Gastrointestinal infections

The enteric E. coli are divided on the basis of virulence properties into enterotoxigenic (ETEC, causative agent of diarrhea in humans, pigs, sheep, goats, cattle, dogs, and horses), enteropathogenic (EPEC, causative agent of diarrhea in humans, rabbits, dogs, cats and horses); enteroinvasive (EIEC, found only in humans), verotoxigenic (VTEC, found in pigs, cattle, dogs, and cats); enterohaemorrhagic (EHEC, found in humans, cattle, and goats), attacking porcine strains that colonize the gut in a manner similar to human EPEC strains) and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAggEC, found only in humans).

Certain strains of E. coli, such as Escherichia coli O157:H7 and E. coli O104:H21, are toxigenic (some produce a toxin very similar to that seen in dysentery) and can cause food poisoning usually associated with eating cheese and contaminated meat (contaminated during or shortly after slaughter or during storage or display).O:157H:7 is further notorious for causing serious, even life threatening complications like HUS (Hemorrhagic Uremic Syndrome). The usual countermeasure is cooking suspect meat "well done"; the alternative of careful inspection of slaughtering and butchering methods (to make sure that the animal's colon is removed and not punctured) has apparently not been systematically tried. This particular strain is believed to be associated with the 2006 United States E. coli outbreak linked to fresh spinach. Severity of the illness varies considerably; it can be fatal, particularly to young children, the elderly or the immunocompromised, but is more often mild. E. coli can harbor both heat-stable and heat-labile enterotoxins. The latter, termed LT, is highly similar in structure and function to Cholera toxin. It contains one 'A' subunit and five 'B' subunits arranged into one holotoxin. The B subunits assist in adherence and entry of the toxin into host intestinal cells, where the A subunit is cleaved and prevents cells from absorbing water, causing diarrhea. LT is secreted by the Type 2 secretion pathway[2]

It has also been shown that STECs, specifically O157:H7 can be found in filth flies on cattle farms, in house flies, can grow on wounded fruit and transmitted to and by fruit flies.[3][4][5]

Since toxigenic coli can be resident in animals which are resistant to the toxin, they may be spread through direct contact on farms, at petting zoos, etc. They may also be spread via airborne particle in such environments.[6] The government asked in 1978 what would the effect be of overfeeding animals antibiotics. The American Academy of Science produced the result that antibiotic resistant E. coli would develop and would be untreatable.

E. coli possess specific nucleation-precipation machinery to produce soluible amyloid oglimers and precipitate them as curli, a network of fibers which bind the bacteria to host cells and each other. The importance of e-coli as a source or amyloid is unknown, but Amyloid fibers are a component of numerous human disease processes including Alzheimer's.[7] [3]

Treatments of E. coli infections

Antibiotic therapy

Appropriate treatment depends on the disease and should be guided by laboratory analysis of the antibiotic sensitivities of the infecting strain of E. coli. As Gram-negative organisms, E. coli are resistant to many antibiotics which are effective against Gram-positive organisms. Antibiotics which may be used to treat E. coli infection include (but are not limited to) amoxicillin as well as other semi-synthetic penicillins, many cephalosporins, carbapenems, aztreonam, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, nitrofurantoin and the aminoglycosides. Not all antibiotics are suitable for every disease caused by E. coli, and the advice of a physician should be sought.

Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem. Some of this is due to overuse of antibiotics in humans, but some of it is probably due to the use of antibiotics as growth promoters in food animals.[8] Resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics has become more serious in recent decades as strains producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases render many, if not all, of the penicillins and cephalosporins ineffective as therapy. Susceptibility testing should guide treatment in all infections in which the organism can be isolated for culture.

E. coli is a frequent member of multispecies biofilms. Some strains are piliated and capable of accepting and transferring plasmids (rings of DNA) from and to other bacteria of the same and different species. E. coli often carry multidrug resistant plasmids and under stress readily transfer those plasmids to other species. Thus E. coli and the other enteroccia are important reservoirs of transferable antibiotic resistance.[9][10]

However, E. coli are extremely sensitive to such antibiotics as streptomycin or gentamycin, so treatment with antibiotics is usually effective. This could rapidly change, since, as noted below, E. coli rapidly acquires drug resistance.[11]

Phage therapy

Phage therapy—viruses that specifically target pathogenic bacteria—has been developed over the last 80 years, primarily in the former Soviet Union, where it was used to prevent diarreha caused by E. coli, among other things, in the Red Army, and was widely available over the counter. [4] Presently, phage therapy for humans is available only at the Phage Therapy Center in the Republic of Georgia [5] or in Poland.[6]

However on January the 2nd, 2007 the FDA gave Omnilytics approval to apply it's 0157:H7 killing phage in a mist, spray or wash on live animals which will be slaughtered for human consumption. [7]

Vaccine

E. coli vaccines have been under development for many years.[12] In March of 2006, a vaccine eliciting an immune response against the E. coli O157:H7 O-specific polysaccharide conjugated to recombinant exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (O157-rEPA) was reported to be safe and immunogenic in children two to five years old. It has already been proven safe and immunogenic in adults.[13] A phase III clinical trial to verify the large-scale efficacy of the treatment is planned.[13]

In January 2007 the Canadian bio-pharmaceutical company Bioniche announced it has developed a cattle vaccine which reduces the number of bacteria shed in manure by a factor of 1000, to about 1000 bacteria per gram of manure.[14][15][16]

Significance in microbiology

E. coli is commonly used as a model organism for bacteria in general. Because of its ubiquity, E. coli is frequently studied in microbiology and is the current "workhorse" in molecular biology. Its structure is clear, and it makes for an excellent target for novice, intermediate, and advanced students of the life sciences. The strains used in the laboratory have adapted themselves effectively to that environment, and are no longer as well adapted to life in the mammalian intestines as the wild type; a major adaptation is the loss of the large quantities of external biofilm mucopolysaccharide produced by the wild type in order to protect itself from antibodies and other chemical attacks, but which require a large expenditure of the organism's energy and material resources. This can be seen when culturing the organisms on agar plates; while the laboratory strains produce well defined individual colonies, with the wild type strains the colonies are embedded within this large mass of mucopolysaccharide, making it difficult to isolate individual colonies.

Bacterial conjugation was first discovered in E. coli, and it remains the primary model to study conjugation.

Because of this long history of laboratory culture and manipulation, E. coli plays an important role in modern biological engineering. Researchers can alter the bacteria to serve as "factories" to synthesize DNA and/or proteins, which can then be produced in large quantities using the industrial fermentation processes. One of the first useful applications of recombinant DNA technology was the manipulation of E. coli to produce human insulin for patients with diabetes. [8]

Significance in determining water purity and sewage treatment

The presence of coliform bacteria in surface water is a common indicator of fecal contamination. This is usually done using the MPN (most probable number) tests. This is usually a probabilistic test which assumes bacteria meeting certain growth and biochemical criteria as E. coli and quantitates it by various methods. "Presence" of E. coli numbers beyond a certain cut-off indicates fecal contamination of water and indicates further investigation into the matter. Often, a "confirmatory" test - the Eijckman test is done which tests for growth at a particular temperature. Many of these tests are routinely done at water storage and distribution systems. At other places, more advanced tests have replaced them. Other organisms like Streptococcus bovis and certain clostridia species are also used as an index of fecal contamination of drinking water sources - usually animal in origin. One of the root words of the family's scientific name, "enteric", refers to the intestine, and is often used synonymously with "fecal". In the field of water purification and sewage treatment, E. coli was chosen very early in the development of the technology as an "indicator" of the pollution level of water, meaning the amount of human fecal matter in it, measured using the Coliform Index. E. coli is used for detection because there are a lot more coliforms in human feces than there are pathogens (Salmonella typhi is an example of such a pathogen, causing typhoid fever), and E. coli is usually harmless, so it can't "get loose" in the lab and hurt anyone. However, sometimes it can be misleading to use E. coli alone as an indicator of human fecal contamination because there are other environments in which E. coli grows well, such as paper mills.

See also

- 2006 North American E. coli outbreak

- Coliform bacteria

- Escherichia coli O157:H7

- Gram-negative

- Theodor Escherich

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Feng, P., Weagant, S. and Grant, M. [Enumeration of Escherichia coli and the Coliform Bacteria]. Bacteriological Analytical Manual (8th ed.) FDA/Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition 2002

- ↑ Escherichia coli O157:H7. CDC Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ↑ Tauschek M, Gorrell R, Robins-Browne RM,. Identification of a protein secretory pathway for the secretion of heat-labile enterotoxin by an enterotoxigenic strain of Escherichia coli. PNAS 99: 7066-7071.

- ↑ Szalanski A, Owens C, McKay T, Steelman C (2004). Detection of Campylobacter and Escherichia coli O157:H7 from filth flies by polymerase chain reaction. Med Vet Entomol 18 (3): 241-6. PMID 15347391.

- ↑ Sela S, Nestel D, Pinto R, Nemny-Lavy E, Bar-Joseph M (2005). Mediterranean fruit fly as a potential vector of bacterial pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol 71 (7): 4052-6. PMID 16000820.

- ↑ Alam M, Zurek L (2004). Association of Escherichia coli O157:H7 with houseflies on a cattle farm. Appl Environ Microbiol 70 (12): 7578-80. PMID 15574966.

- ↑ Christie, Tim, "Tests suggest E. coli spread through air", The Register-Guard, 2002-09-24. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ↑ Chapman M, Robinson L, Pinkner J, Roth R, Heuser J, Hammar M, Normark S, Hultgren S (2002). Role of Escherichia coli curli operons in directing amyloid fiber formation. Science 295 (5556): 851-5. PMID 11823641.

- ↑ Johnson J, Kuskowski M, Menard M, Gajewski A, Xercavins M, Garau J (2006). Similarity between human and chicken Escherichia coli isolates in relation to ciprofloxacin resistance status. J Infect Dis 194 (1): 71-8. PMID 16741884.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Gene Sequence Of Deadly E. Coli Reveals Surprisingly Dynamic Genome. Science Daily (2001-01-25). Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ Girard M, Steele D, Chaignat C, Kieny M (2006). A review of vaccine research and development: human enteric infections. Vaccine 24 (15): 2732-50. PMID 16483695.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Ahmed A, Li J, Shiloach Y, Robbins J, Szu S (2006). Safety and immunogenicity of Escherichia coli O157 O-specific polysaccharide conjugate vaccine in 2-5-year-old children. J Infect Dis 193 (4): 515-21. PMID 16425130.

- ↑ Pearson H (2007). The dark side of E. coli. Nature 445 (7123): 8-9. PMID 17203031.

- ↑ New cattle vaccine controls E. coli infections. Canada AM (2007-01-11). Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ Bioniche Life Sciences Inc. (2007-01-10). Canadian Research Collaboration Produces World's First Food Safety Vaccine: Against E. coli 0157:H7. Press release. Retrieved on 2007-02-08.

External links

General

Health aspects

- FDA information on the Spinach and E. coli Outbreak

- E. coli Outbreak From Fresh Spinach - U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Genomics

- EcoCyc: Encyclopedia of E. coli genes and metabolism

- coliBASE: a comparative genomics database for E. coli

- EchoBASE: an integrated post-genomic database for E. coli

- The E. coli index: resource for E. coli as a model organism

- E. coli CFT073 Genome Page

- E. coli K12-MG1655 Genome Page

- E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 Genome Page

- E. coli O157:H7 VT2-Sakai Genome Page

- E. coli UTI89 Genome Page

- E. coli Serotypes

Further reading

- Coliform Bacteria and Nitrogen Fixation in Pulp and Paper Mill Effluent Treatment Systems - by Dr. F. Archibald (full text)

- Scientists are synthetically engineering E. coli that can target and kill cancer cells

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.